Near-Death and Afterlives

The second half of the 20th century was a period of decline for Hispanofilipino literature. The promotion of a Tagalog-based national language called Filipino, the removal of Spanish as a required course in Philippine high schools and universities, the spread of English in mass media, and the change in the legal status of Spanish, which went from being an official language to an optional language in the late 1980s, all contributed to this decline.

From the late 1960s onwards, social attitudes toward Spanish were becoming increasingly unfavorable. There were sectors of society protesting the obligatory teaching of Spanish in schools because it was perceived as an elitist language spoken by those who were close to the regime that would eventually place the Philippines under Martial Law in 1972. Ironically, it was the Martial Law Constitution of 1973 that first broached the idea of demoting Spanish from its official status, only to be halted by a temporary reprieve issued by the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. When a popular revolt ousted Marcos in 1986, the new Constitution promulgated afterwards determined that Spanish would henceforth be an optional language that could be taught on a voluntary basis.

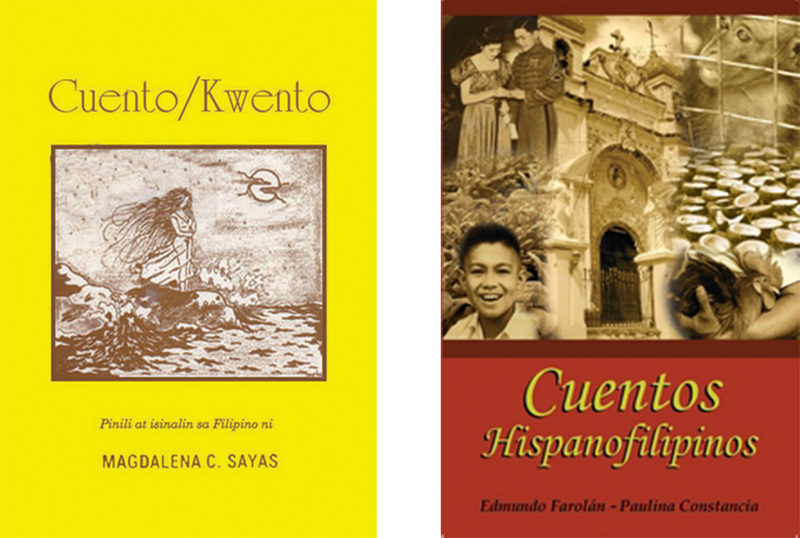

Translation was what allowed Hispanofilipino literature to survive during these turbulent times. Works previously authored in Spanish were published again as bilingual editions during this period, such as Pilar E. Mariño’s Philippine Short Stories in Spanish, 1900-1941. From Mariño’s translation to English came Magdalena Sayas’s own translation anthology in Filipino called Cuento / Kwento. Pictured above on the left is an image of the cover. Bright yellow, with a simple black and white illustration in the middle of the cover, the cover depicts a woman with long hair in a dress standing on a rock as ocean waves crash against it, and the moon partially hidden by clouds in the background. Above the illustration is the title Cuento / Kwento, and below it reads, in Filipino, “selected and translated into Filipino by Magdalena C. Sayas.” Antonio M. Abad’s La oveja de Nathán, which was published in installments in the newspaper La Opinión, won the Zóbel Prize in 1929. In 2013 it was published in book form with a parallel translation in English by Lourdes Brillantes.

The changes in the language politics of the Philippines also pushed some Hispanofilipino authors to practice literary translingualism, or writing a literary text in two or more languages. Since Spanish was no longer a required subject in schools and universities, the surest way for Filipino authors in Spanish to have their works read was to publish them either with a parallel translation or as components of multilingual anthologies. The translations were mostly done in English, which by this time had already consolidated its status as the language of education. The most important exponent of literary translingualism in Hispanofilipino literature was perhaps Federico Espino Licsi. A prolific writer who wrote in Spanish, English, Tagalog and Ilocano, he has published several self-translations and anthologies such as In Three Tongues, Ave en jaula lírica (Bird in the Lyric Cage), and Opus Almost Posthumous. Other translingual works in modern-day Hispanofilipino literature include Itinerancias / Comings and Goings by Edmundo Farolán, Cuentos hispanofilipinos / Hispano-Philippine Stories by Edmundo Farolán and Paulina Constancia, and Witch’s Dance and Cadena de amor by Marra Lanot. The cover Cuentos hispanofilipinos is pictured above, to the right of the Cuento / Kwento cover. The lower half of the first book is dark red, its title, Cuentos Hispanofilipinos, written in a flowing script above the authors’ names. The upper half of the cover is a sepia toned collage of photos: in the middle, dominating, is the front of a church, and on the left is an image of a couple above an image of a smiling boy in a field. On the right is a picture of a caged monkey above the image of rows of coconut halves, below which a rooster is cradled in someone's hands.

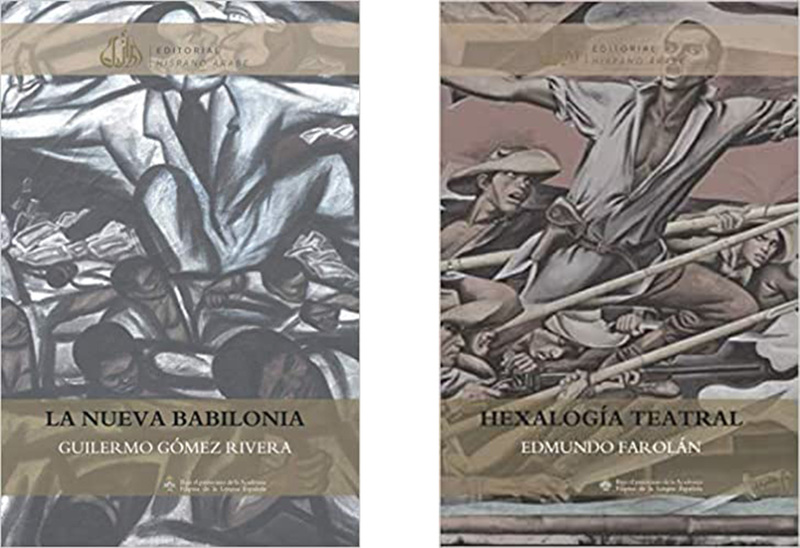

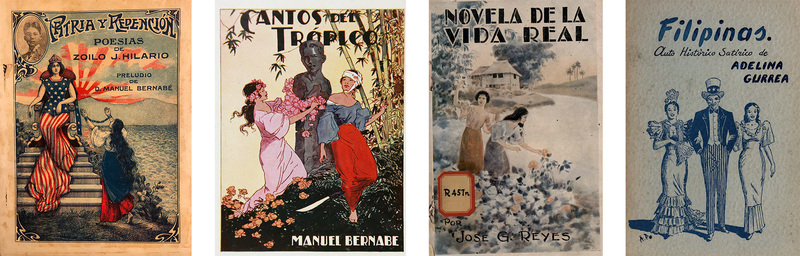

Of late, a few monolingual books were published in the Colección Oriente series of the Barcelona-based publishing house Editorial Hispano Árabe. The two titles we have in U-M so far are Guillermo Gómez de Rivera’s La nueva Babilonia (The New Babylon) and Edmundo Farolán’s Hexalogía teatral (Theatrical Hexalogy). The book cover of La nueva Babilonia, above on the left, is a detail from the painting Comprador (“Buyer”) by Pablo Baens Santos from 1978, which is on display at the National Museum of the Philippines. In black and white, two male figures in suits dominate the upper half of the cover, grinning and waving money, representing politicians from the Philippines and the US exchanging money. The dark-skinned figures frowning underneath them represent the Filipino masses. The book cover of Hexalogía teatral, above on the right, is a detail from the mural Filipino Struggles through History by Carlos "Botong" Francisco, one of the Philippine National Artists for Visual Arts. The mural was installed originally in the Manila City Hall in 1968, but was later transferred to the National Museum and was declared a National Cultural Treasure of the Philippines in 1998. In light greys and browns, the cover shows figures bearing spears, rifles, and cutlasses, heading for the right side of the cover as if into battle. The central figure on the cover is Andrés Bonifacio, the founder of the Katipunan, the independence movement that led the popular revolt against Spain. He wears a long shirt tucked into a belt with a pistol. His arms stretch off either side of the cover so you cannot see his hands, but his mouth is open as if speaking. He appears to be leading the charge. Both Gómez de Rivera and Farolán are members of the Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española (Philippine Academy of the Spanish Language). Additionally, the Instituto Cervantes de Manila, the cultural arm of the Spanish Government in the Philippines, has started a series called Clásicos hispanofililipinos, which aims to recover Hispanofilipino masterpieces in their original language. The U-M Library has received a donation of the first three titles of the series: Cuentos de Juana (Tales of Juana) by Adelina Gurrea, Los pájaros de fuego (Birds of Fire) by Jesús Balmori, and El campeón (The Champion) by Antonio Abad.

It may be tempting at first glance to contain the Spanish Philippines within that period between 1565 and 1898 when the islands were under Spanish rule. But what this virtual exhibit shows is that the literary worlds of the Spanish Philippines sprawl across different times and spaces. The development of Hispanofilipino literature happened alongside historical events that greatly defined Filipino society: from early cultural and commercial contacts with its neighbors in Asia to a transoceanic encounter with Spain and Latin America; from the consolidation of Spanish colonialism to its fall and subsequent replacement with US imperialism; from the rise of Filipino nationalism that found its most sublime expression in Spanish, to modern-day efforts of get rid of Spanish for being an elitist language. The multilingual and multicultural condition that has so characterized the Filipino nation throughout it history compels us to rethink of Hispanofilipino literature in terms of its translationality, for it is through translation that Hispanofilipino literature continues conversing with a nation in transit.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Donoso, Isaac, and Andrea Gallo. 2011. Literatura hispanofilipina actual (Hispanofilipino Literature at Present). Madrid: Verbum.

Ortuño Casanova, Rocío. 2017. “Philippine Literature in Spanish: Canon Away from Canon.” Iberoromania (85):58-77. doi: 10.1515/iber-2017-0003.

A Golden Age?

About the Exhibit