A Historically Multilingual Space

It would be incorrect to characterize the Spanish Philippines as monolingual. During a period when knowledge about Philippine languages was still developing, European chroniclers were already aware that the people living across the archipelago’s more than seven thousand islands spoke different languages. These people had been actively trading with their neighbors in Asia, especially the Chinese and the Malays, even before the first colonial settlements were established following the arrival of the Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565.

The US Midwest is home to one of the most enduring literary records of this cultural diversity: the Boxer Codex, named after its former owner, Professor Charles Boxer. Found at present in the Lilly Library of Indiana University, the Boxer Codex is a unique manuscript from the late sixteenth century containing narrative and visual portrayals of the people living in and around the Philippine archipelago.

These three illustrations from the Boxer Codex depict some of the indigenous peoples living in the Philippines in their traditional garments. Each page has a colorful border of green vines, blue flowers, red and gold flowers, blue birds, and what seem to be brown civet cats. At the top of each page, the name of the group is written in gold ink. From left to right, the first couple are the Tagalogs from Luzon (whom the Spaniards called naturales, or natives) wearing bright red and shades of purple with gold necklaces and bracelets worn at their wrists and knees. The second couple are the Visayans, with their characteristic tattooed skin (and whom Spaniards called Pintados, or the Painted Ones). The man on the left wears orange with a matching putong, or headwrap, and the woman beside him wears pink and blue. The third couple are Negrillos (or Negritos), and both wear white wristbands and loincloths. The man on the left carries a bow, while the woman to the right carries arrows.

The Boxer Codex also featured drawings of people from other parts of Asia, as pictured above in the three images. Seen from left to right, the first couple are the Sangleyes, the term the Spaniards used to call the Chinese in the Philippines. The man on the left wears a blue robe and a black headdress and holds a fan. The woman wears green and pink. The second couple are the Japanese, pictured here holding fans and wearing blue. The man on the left wears a pair of sandals and has a katana strapped around his waist, and the woman wears red shoes. The third couple are the Tartar from northeast Asia. They wear feathered hats and fur-lined garments in green, yellow, blue and pink. All the drawings are set against a white background, devoid of illustrated geographical context, which suggests that they may have been intended to provide a visual inventory of the different peoples the Spaniards encountered in Asia.

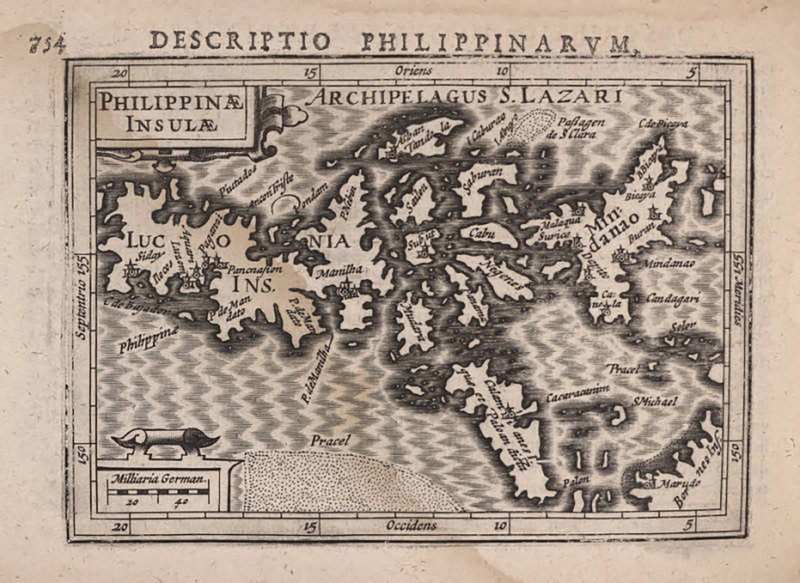

Midwestern libraries also have maps that give us early cartographic depictions of the Philippines. Most notably, the Descriptio Philippinarum (Description of the Philippines) by the Flemish cartographer Petrus Bertius (Pieter de Bert) is among the first known maps showing the expanse of the Philippine islands. First published in 1598, the picture above comes from the 1616 edition owned by the James Ford Bell Library of the University of Minnesota. Labeled in Latin and printed sideways, the Descriptio Philippinarum has a rectangular border indicating longitude and latitude. Dark shading indicates the coasts of the islands, and lighter shading in zigzags indicates the sea. Below the text that reads “Descriptio Philippinarum,” the map reads Archipelagus S. Lazari (Archipelago of St. Lazarus), the name given to the Philippines by Ferdinand Magellan, who first saw the islands on Lazarus Saturday, the day before Palm Sunday, under the old Julian calendar.

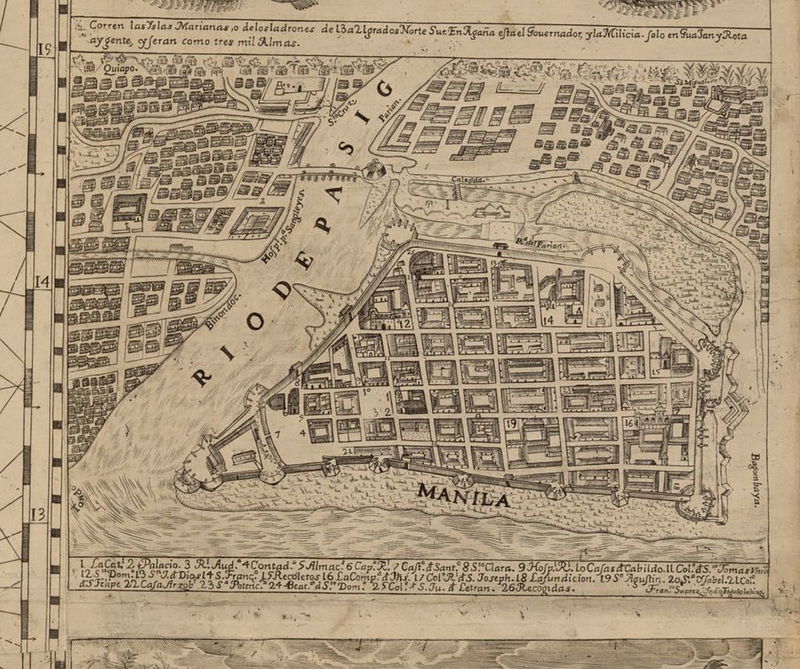

Old maps of Manila are likewise accessible. Manila was the transoceanic commercial hub of the so-called Manila Galleons, which from 1565 to 1815 connected the port of the Philippine capital to that of Acapulco in Mexico. This trade route turned Manila into a site of cultural and linguistic contact between East and West. People from different places converged in Manila, where silk and porcelain from China, spices from Moluccas, ivory carvings from Manila, and a host of other Asian goods were exchanged for Mexican silver.

The map of Manila pictured above is taken from the Carta hydrographica y chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas (Hydrographic and Chorographic Map of the Philippine Islands) of the Library of Congress. The space labeled as Manila on the map was “Intramuros,” the walled Spanish enclave surrounded by the Pasig River where several churches, monasteries, schools, various government buildings, and the cathedral were located. Also visible are the neighborhoods of Binondoc (present-day Binondo) and the Parian where the Sangleyes lived.

But to get a better sense of how diverse colonial Manila was, we can always turn to historical narratives from the period.

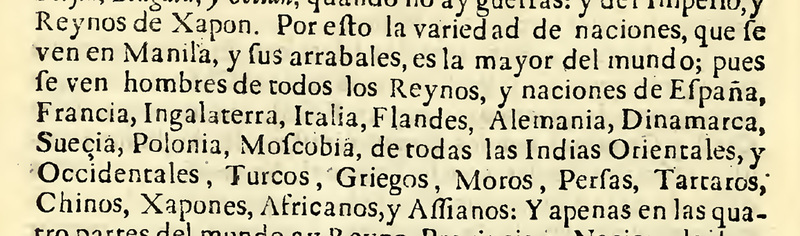

For instance, in this passage from the 1662 book Perfecta religiosa (The Perfect Nun), the Franciscan priest Bartolomé de Letona described the cultural diversity in Manila as the greatest in the world, with visitors coming from Spain, France, England, Italy, Flanders, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Muscovy, the East and West Indies, as well as Turks, Greeks, Moors, Persians, Tartars, Chinese, Japanese, Africans, and Asians. A copy of Letona’s book can be found in the Lilly Library in Indiana.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Ellis, Robert Richmond. 2012. They Need Nothing: Hispanic-Asian Encounters of the Colonial Period. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Padrón, Ricardo. 2020. The Indies of the Setting Sun: How Early Modern Spain Mapped the Far East as the Transpacific West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Scott, William Henry. 1992. Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Souza, George Bryan, and Jeffrey Scott Turley, eds. 2016. The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, Ethnography and History of the Pacific, South-East Asia and East Asia. Leiden: Brill.

The Spanish Philippines in the US Midwest

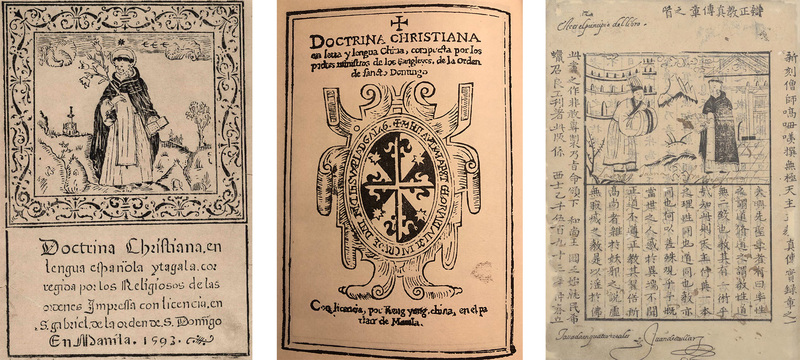

Missionary Writing