Resisting English

It was through US colonization that English entered the Filipino literary world. American teachers, popularly referred to as the Thomasites, were sent to the Philippines to help in the efforts of the colonial government to expand the public school system. Many of these teachers were from the Midwest, particularly Michigan, thus earning them the nickname of “Michigan Men.” They were from different Michigan institutions such as Albion College, Kalamazoo College, Olivet College, Michigan State Normal School (Eastern Michigan University at present), and the University of Michigan. U-M was the second biggest contingent with 24 members, only bested by the University of California with 25. The personal papers of Frederick G. Behner of Ohio and Morton Netzorg of Michigan in the U-M Bentley Historical Library give us eyewitness accounts of the work of the Thomasites. Netzorg was a prolific writer who also ventured out to translate some literary pieces from Filipino and Spanish to English, or what he described in one manuscript as an “Englishing” of texts.

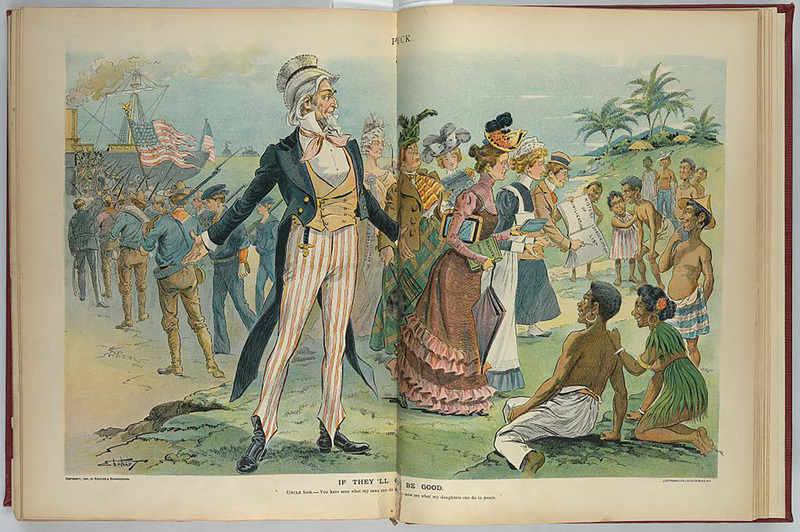

Above is a political cartoon from the satirical magazine Puck done in watercolor. In the foreground, Uncle Sam gestures to the right and left. Behind him are American soldiers walking to board a Navy ship. One of them holds a torn American flag. In the foreground on the right-hand side of the image are white women–1800s school teachers–holding books, one of which is open and says “History of Civilization.” Books in hand, the women walk toward the Filipinos on an island with palm trees and the coast in the background. Some of the Filipinos look curious and some confused, some of them with racially exaggerated facial features, but generally seeming to welcome the “teachers.” The cartoon is captioned “If they'll only be good,” and then on a line below it, “Uncle Sam.– You have seen what my sons can do in war – now see what my daughters can do in peace.”

The University of Michigan played a key role in the US imperialist project. One of U-M’s most prominent alumni, Dean C. Worcester, became the US Secretary of Interior of the Philippine Islands.

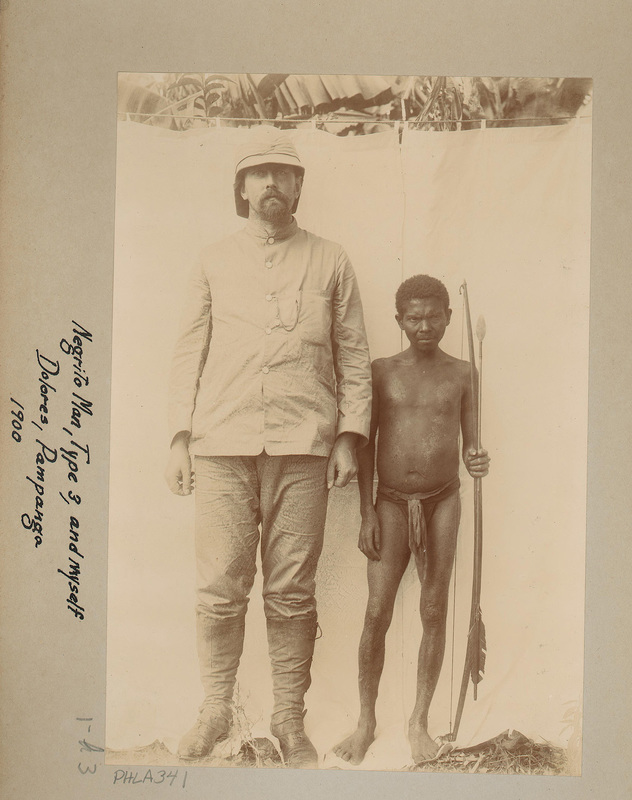

Photographed in front of a white sheet hung on a line behind them, Worcester stands to the left of an unnamed Negrito. Worcester sports a pith helmet and a goatee, with a light-colored suit and boots. He has a watch chain tucked into his shirt pocket and looks directly at the camera. The Negrito is barefoot and wears a loincloth. Standing on the edge of the sheet, he holds a bow and a singular arrow in his right hand. His eyebrows are furrowed and squints at something to the photographer's right.

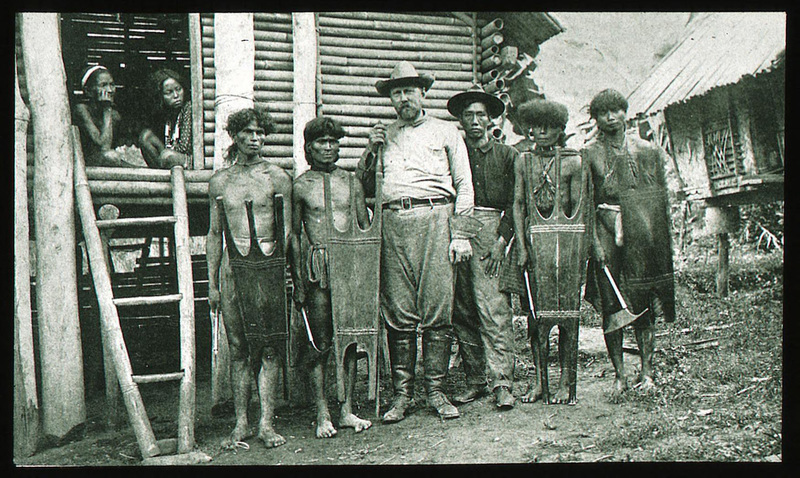

The image above depicts four unnamed Kalinga chiefs from the Philippine highlands, all wearing small necklaces and loincloths and standing in front of a nipa hut. The men hold hand axes and long, narrow shields. The shields have two long prongs at the bottom, and three long prongs at the top. A few horizontal lines are etched directly above and below the prongs on the shields. Worcester, in a hat and leaning on a staff, stands in the middle of the group. To the right and slightly behind him stands an unnamed man with dark skin, dressed similarly to Worcester, who may have been a local recruited to be his guide. In the background, at the door of the nipa hut, two women sit and watch the men in the line.

He also headed a fact-finding mission, the objective of which was to gather archaeological, anthropological and pictorial information on the new colony. Worcester’s controversial research methods, which involved incursions into ancestral lands in search of precious metals, earned the ire of Filipino nationalists. The newspaper El Renacimiento published its most famous editorial entitled “Aves de rapiña,” or “Birds of Prey,” in criticism of Worcester. It was Worcester who brought back his collection of papers, photographs and other effects on the Philippines to Michigan; this collection is now curated as the Worcester Philippine History Collection.

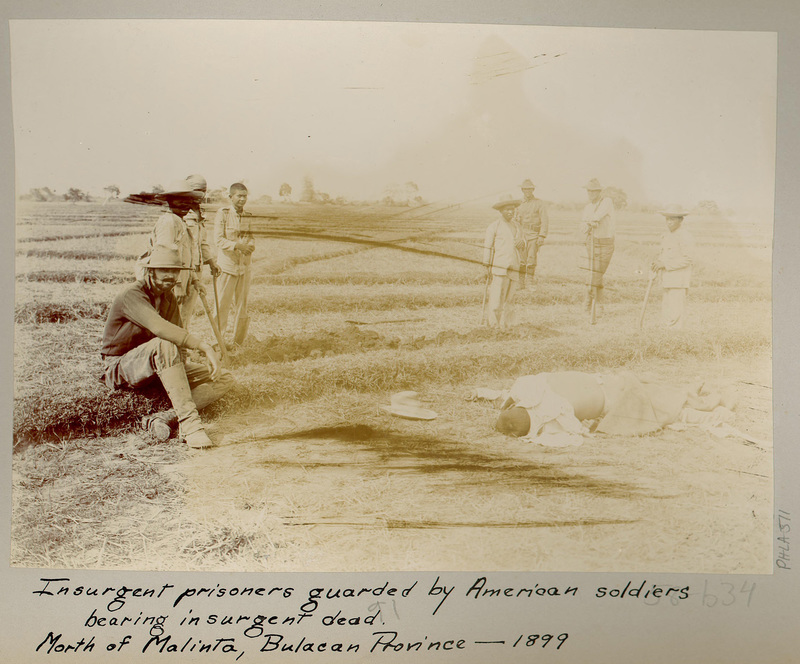

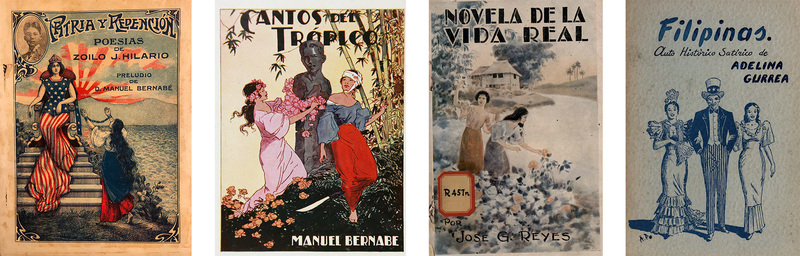

For Hispanofilipino authors, the English language was the symbol of the tyranny of the new colonial regime. A common theme in Hispanofilipino literature from this period was the rejection of English as a vehicle of US imperialism and the praise for Spanish as a language of the Filipino nation. Cecilio Apóstol taunted the US for its imperialist agenda in the Philippines in his 1899 poem “Al ‘Yankee’” (To the Yankee) from the anthology Pentélicas, adding that his verses would forever serve to memorialize the oppression of the Filipinos. For his part, Rafael Palma poignantly described the violence of English as it slowly displaced Spanish in one of his essays in the book Voces de aliento (Voices of Encouragement). Palma warned that the American wave engulfing Manila would leave no trace of the city’s once glorious existence behind.

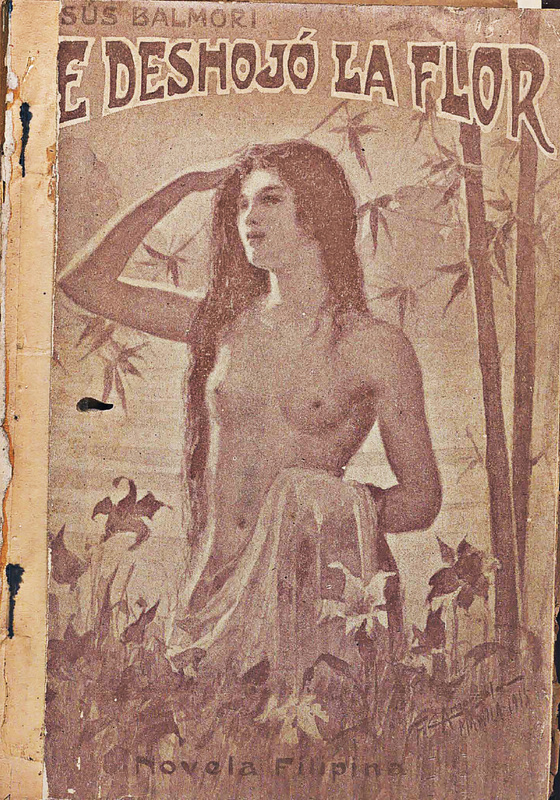

At the top of this faded 1915 cover of the novella Se deshojó la flor (The Flower Has Withered) is the novel's title and author, Jesús Balmori, printed at the top. On the bottom of the cover, in smaller print is the phrase “Novela Filipina” (Filipino Novel). The illustration on the cover is a woman in front of a body of water, small trees to her right, and flowers in front of her, covering her lower half. The woman is nude, but her right hand holds a cloth in front of her stomach, and with her left hand, she pushes her long dark hair out of her face.

Jesús Balmori’s Se deshojó la flor kept to this theme, poking fun at the new values and social customs the Americans introduced in Filipino society. English was becoming a language of new opportunities for Filipinos, yet there were people like Balmori, one of the most prominent Filipino writers of all time, who associated it with blind ambition and a loss of innocence. At one point in this novella, Rafael, the main character, maintained that he would much rather have his sisters gather hay from the fields than see them learn English and flirt with Americans. “Está loca ahora por el inglés; debe tener algún novio americano,” (She’s obsessed with English; she must have found an American boyfriend), Rafael quipped.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Kirkwood, Patrick M. . 2014. “‘Michigan Men’ in the Philippines and the Limits of Self-Determination in the Progressive Era.” The Michigan Historical Review 40 (2):63-86. doi: 10.5342/michhistrevi.40.2.0063.

Rice, Mark. 2014. Dean Worcester's Fantasy Islands: Photography, Film, and the Colonial Philippines. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Rodao, Florentino. 1997. "Spanish Language in the Philippines: 1900-1940." Philippine Studies 45 (1):94-107.

Steinbock-Pratt, Sarah. 2019. Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Between Two Powers

A Golden Age?