A Golden Age?

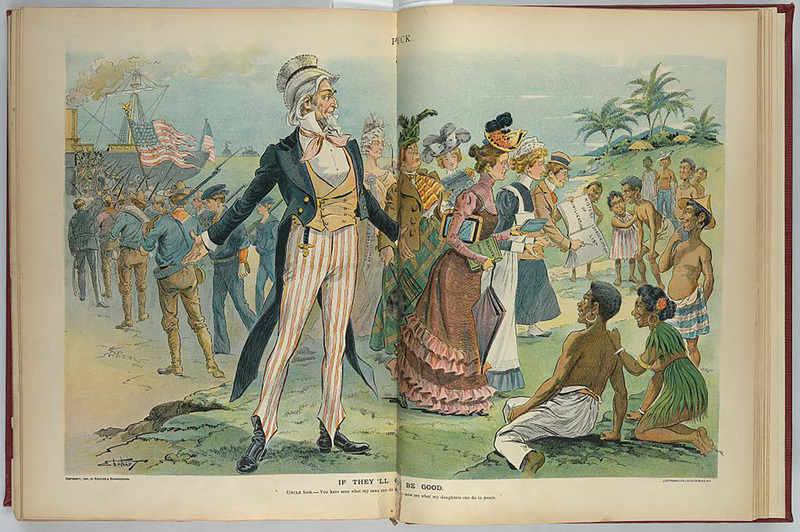

The US rule in the first half of the twentieth century ironically paved the way for Hispanofilipino literature to have some sort of a golden age. As a response to the imposition of English, the production of Filipino literature in Spanish became more abundant than in previous periods. There was enough interest in the local communities to sustain this literary tradition. Bilingual newspapers between Spanish and indigenous languages circulated in different parts of the archipelago. The Zóbel Prize was established in 1920 to recognize writers and advocates of Hispanism in the Philippines.

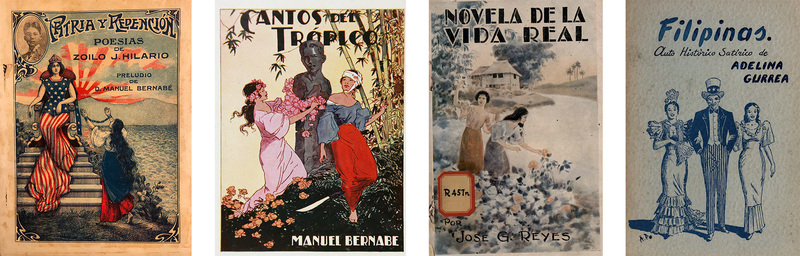

Copies of some of the Hispanofilipino masterpieces from this period have found their way to the U-M Library, such as Fernando Ma. Guerrero’s Crisálidas (Chrysalides), Zoilo Hilario’s Patria y redención (Motherland and Redemption), Manuel Bernabé’s Cantos del trópico (Songs from the Tropics), Guillermo Gómez Wyndham’s La aventura de Cayo Malinao (The Adventure of Cayo Malinao), José G. Reyes’s Novela de la vida real (Novel of the Real Life), José Santiago Villacorta’s Entre dos generaciones (Between Two Generations), and Adelina Gurrea’s Cuentos de Juana (Juana’s Tales) and Filipinas: auto histórico-satírico (Philippines: Historic-Satirical Play). Pictured above are four of the books, from left to right: On the cover of Patria y redención, published in 1914, we see an oval portrait of the author in the upper left-hand corner, next to the script of the title. On the left side of the cover, there is a crowned woman wearing a long bustier gown, the top half blue with white stars, and the skirt of it red and white stripes. She sits on a throne at the top of some stairs. In the foreground, there is a woman with long, dark hair. She runs toward the crowned woman, her shackled hands reaching towards her. In the background, there is a body of water and the sun, drawn as a simple red disc with rays. Cantos del trópico, published in 1929, features the title in an Art Deco-style font in the top center of the cover. From right to left, we see a forest of bamboo that opens up giving space to two figures, a man (wearing a bright blue shirt and bright red pants) and a woman (wearing a pale yet bright pink dress), flanking a bust of Bernabé himself. The man’s body is turned away from the bust and there is a machete at his feet. The woman decorates the bust with a string of pink flowers, some of which she also wears in her hair. Published in 1930, the watercolor cover of Novela de la vida real is more pale than the covers of the previous two books described. The hues of Novela are muted blues and greens. Two women stand in the foreground, picking flowers alongside the bank of a river. One of them waves at somebody out of frame, and in the background there is a two-story house. The final featured book cover is of Filipinas: auto histórico-satírico, published in 1954. Painted in monochrome (blue) on a lightly textured paper are three figures beneath the title: two women flanking Uncle Sam, who wears the typical tailcoat, bow tie, striped slacks, and top hat with blue band and white stars. The woman on the left, wearing a cross around her neck, also dons a Flamenco-style dress and holds in one hand a fan. On his right, the woman wears a slim-fitted terno dress with the characteristic butterfly sleeves.

Also worth mentioning is Epifanio de los Santos’s translation to Spanish of the Florante at Laura, an eponymously named Tagalog awit (metrical romance) originally written by Francisco Balagtas about two lovers from the nobility of the Kingdom of Albania who were separated from each other by an usurper to the throne. The translation was published in the July 1916 issue of the bilingual magazine Revista filipina / The Philippine Review, followed by a critical analysis in the August 1916 issue. Later Hispanofiipino authors include the daughters of Fernando Ma. Guerrero, the poets Evangelina Guerrero Zacarías, who wrote Kaleidoscopio espiritual (Spiritual Kaleidoscope) in 1959, and Nilda Guerrero Barranco, whose Capullos (Buds) came out in 1982.

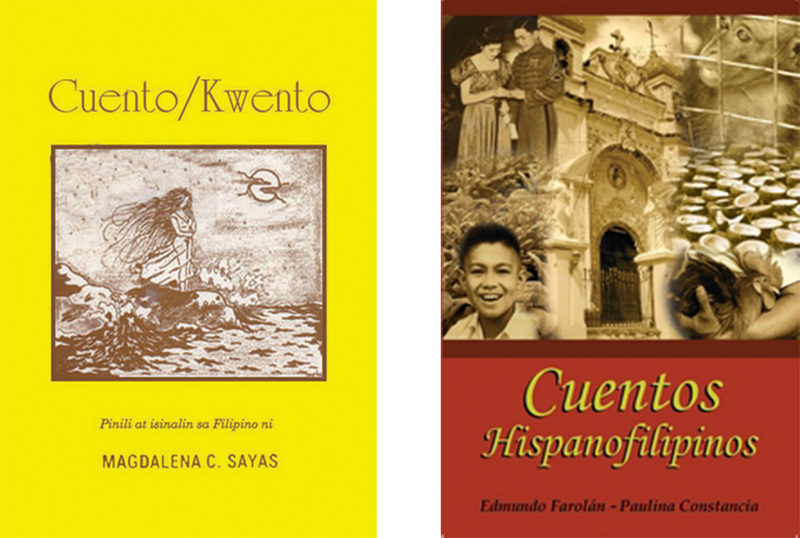

The fact that there were people as late as the 1940s and 1950s who could read Spanish also meant that only a few Hispanofilipino masterpieces have been translated. The U-M has a modest collection of these translations: Teodoro Kalaw’s Dietario espiritual has been translated to English by Nick Joaquin, one of the Philippine National Artists for Literature. Kalaw’s Cinco reglas de nuestra moral antigua has been translated to English and to Tagalog by his daughter, the Filipino politician María Kalaw Katigbak. Alfredo S. Veloso has translated José Palma’s Melancólicas as Melancholies, Claro M. Recto’s Bajo los cocoteros as Beneath Coconut Palms, and Enrique Laygo’s Caretas as Masks. The dearth of translations partly explains the invisibility of Hispanofilipino literature at present. Many works have remained inaccessible for the national readership that no longer understands Spanish.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Brillantes, Lourdes Castrillo. 2006. 81 Years of Premio Zóbel: A Legacy of Philippine Literature in Spanish. Makati: Georgina Padilla y Zóbel and the Filipinas Heritage Library.

Fernández, Mauro. 2013. “The Representation of Spanish in the Philippine Islands.” In A Political History of Spanish: The Making of a Language, edited by José del Valle, 364-379. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lifshey, Adam. 2016. Subversions of the American Century: Filipino Literature in Spanish and the Transpacific Transformation of the United States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Peralta-Imson, María Elinora. 1997. “Philippine Literature: Spanish Evolving a National Literature.” Linguae et Litterae II:1-19.

Resisting English

Near-Death and Afterlives