Indigenous Voices

The early history of print literature in the Spanish Philippines is populated with references to European authors. Only a few indigenous voices were preserved in the surviving records from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. We know of Tomás Pinpín, who in 1610 published the first grammar of Spanish in the Tagalog language. Less famous than Pinpín but no less important was Bartolomé Saguinsín, an indigenous priest whose 1766 collection of Latin epigrams memorialized the British invasion of Manila between 1762 and 1764.

The inaudibility of indigenous voices in literature also applies to translation. One of the major challenges in researching translation in the Spanish Philippines is the dearth of materials on the translators themselves. Because translation was regarded as an ancillary skill, the figure of the translator was generally subsumed under other professions, such as that of a priest or a municipal judge.

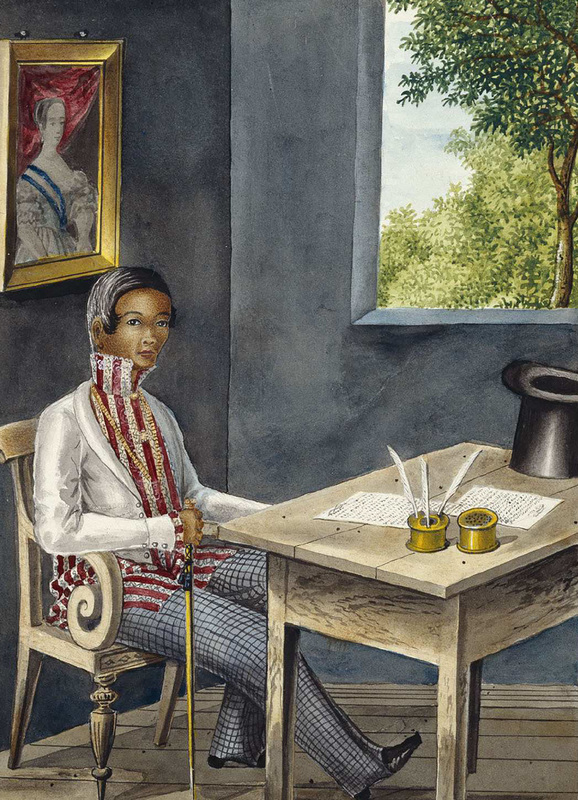

These watercolor paintings from the 1847 Vistas de las Yslas Filipinas y trages de sus habitantes (Scenes from the Philippine Islands and Costumes of their Inhabitants) by the Filipino painter José Honorato Lozano give us an idea of how these people might have looked like. The first watercolor depicts a native gobernadorcillo, (literally, “little governor”), or municipal judge, sitting at a desk. The man wears a high-collared white and red striped shirt with gold buttons, and a gold necklace. He has a white overcoat and grey pants, and he holds a gold cane. On top of the desk is resting a black top hat, a few quills and an inkpot, and two sheets of paper with writing on them. To his side, there is an open window overlooking a few trees, and hanging on the wall behind the man is a portrait of Queen Isabella II, who reigned over Spain at the time when the watercolor painting was produced.

The second watercolor painting portrays an indigenous Filipino priest in a wide-brimmed black hat and black robes with a white clerical collar. In his left hand, he holds a yellow pointing stick, and with his right hand, he pats the head of a boy wearing a striped shirt and pants and a yellow scarf. The boy holds a white pillow with a Spanish-style bonete (clerical biretta) resting on it. The watercolor is captioned "Cura Indio" (Indio priest).

The gobernadorcillo was among the few positions of leadership that indigenous Filipinos could ever aspire for in the colonial government. Among the requirements for the role was knowing Spanish. Indigenous Filipinos could also enter the seminary and join the clergy. In addition to Spanish, clergymen were expected to understand enough Latin to lead church services. The Ayer Collection of the Newberry Library of Chicago has one of the oldest known historical accounts written by an indigenous Filipino, Juan Masolong’s 17th century manuscript about the founding in 1572 of the town of Liliw in Laguna province, about 65 kilometers southeast of Manila.

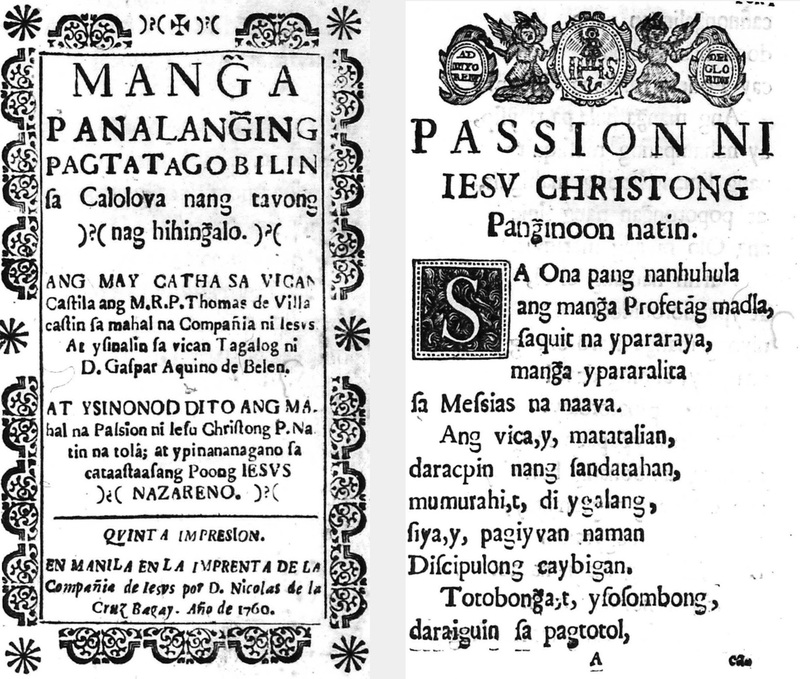

The Bartlett Collection on the Philippines and the East Indies of the University of Michigan Library has a digitized copy of the what seems to be the only surviving edition from 1760 of Manḡa panalanḡin sa pagtatagobilin sa caloloua nang tauong naghihinḡalo (Prayers of Commendation for the Souls of the Dying), Gaspar Aquino de Belén’s Tagalog translation of a book of prayers by the Spanish Jesuit Tomás de Villacastín.

Pictured above, from left to right, are two black and white pages from Manḡa panalanḡing pagtatagobilin sa caloloua nang tauong naghihinḡalo (Prayers of Commendation for the Souls of the Dying), a Tagalog translation of a Spanish book of prayers. The first page is the cover page, displaying the title, authors, and the place of publication. The border around the coverpage has thick outlines of semi-circles, with a curled design inside that stops at the thin rectangular border around the text. The other page is the first page of the pasyon, the Philippine epic poem about the life of Jesus Christ, written in Tagalog. At the top of the page is a depiction of angels around a coat of arms.

What makes this book important in the history of Filipino literature is the appended text popularly known as the pasyon, a long poem written in Tagalog in the style of a Spanish quintilla (five-line verse) narrating the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The pasyon is still chanted to this day as a popular Filipino devotional practice during Lent.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Javellana, Rene B. 1984. “The Sources of Gaspar Aquino de Belen’s Pasyon.” Philippine Studies 32 (3):305-321.

Lee, Christina H., and Ricardo Padrón, eds. 2020. The Spanish Pacific, 1521-1815: A Reader of Primary Sources. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Lumbera, Bienvenido. 1986. Tagalog Poetry, 1570-1898: Tradition and Influences in its Development. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Woods, Damon L. 2011. Tomas Pinpin and Tagalog Survival in Early Spanish Philippines. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House.

Missionary Writing

Filipino Enlightenment