Between Two Powers

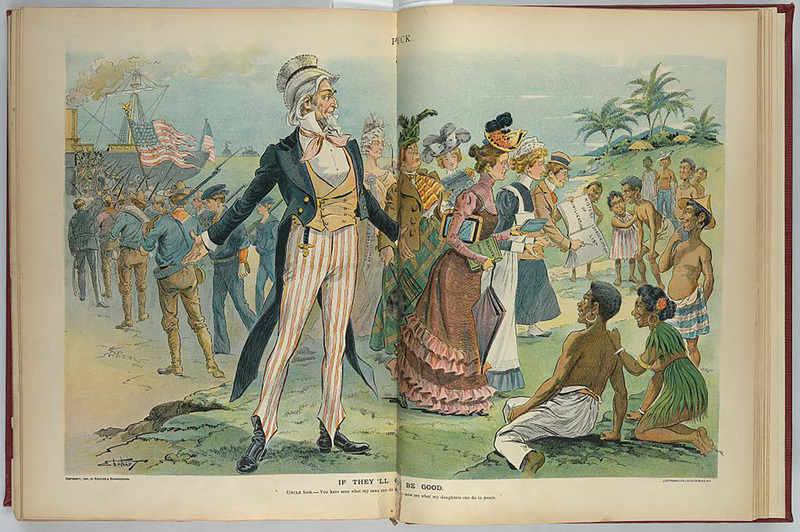

A selection of materials displayed on this page contains culturally sensitive or racist content and may be considered offensive by some viewers. The materials are presented as a representation of cultural history for evaluation and critique. This is not an endorsement from the library but offered as a method to confront challenging histories associated with the objects through scholarship and discussion. Please use your discretion while exploring this page.

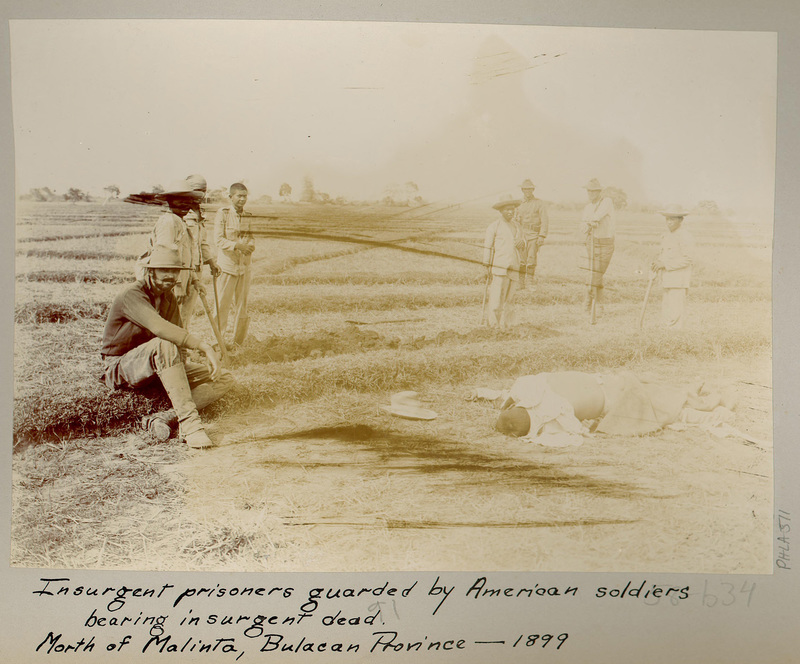

The Philippines declared independence from Spain on June 12, 1898. Instead of recognizing the declaration, Spain signed the Treaty of Paris on December 10 of that same year, thus ceding control over the islands to the US. The transition between two colonial powers did not happen smoothly. By 1899 the Philippine-American War broke out. The Philippine Photographs Digital Archive of the University of Michigan is a valuable visual resource for researching this period. Many of the archived images of the Filipino-American War are of Filipinos killed in battle. Many photographs, such as those included in this exhibit, portray corpses lined up for mass burial; it is rare to find images of Americans dead. It has been argued that the widespread circulation and archiving of these violent images of dead Filipino insurgents function as part of the American imperialist project. We see two of these images below. The first depicts insurgents captured and guarded alongside their fallen compatriots by American soldiers in the Bulacan Province.

The picture above of the bodies of dead Filipino insurgents–as they were referred to by the Americans–who were killed while attempting to escape from a trench and lined up in a rice paddy, shows how violent this war was. The Philippine-American War resulted in the deaths of many Filipinos, insurgents and civilians alike.

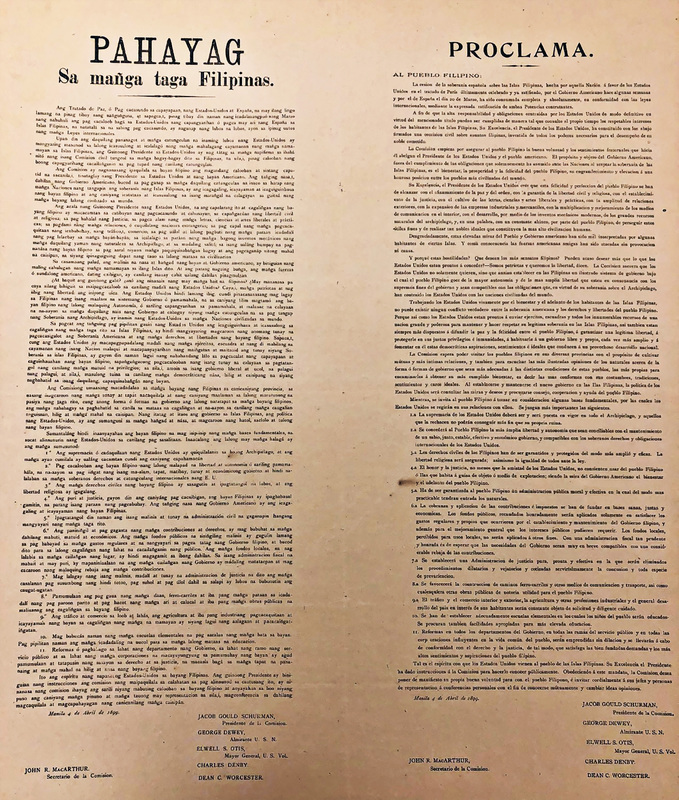

Part of the U-M collection is a copy of the proclamation creating the First Philippine Commission in 1899 written in both Tagalog and Spanish. Titled bilingually as Pahayag sa mañga taga Filipinas / Proclama al pueblo filipino, the proclamation was printed on a broadside sheet measuring 71 x 61 cm. The proclamation boldly declared that US supremacy must be recognized by the Philippines. Whoever refused to do so “no podrán conseguir más fin que su propia ruina” (will not achieve anything other than their own downfall).

The First Philippine Commission was headed by Jacob Schurman, who was then the President of Cornell University. The main task of the First Philippine Commission was to examine the political and social situation of the Philippines and make recommendations to US President William McKinley. It was this commission that determined that the Filipinos were not ready for independence. It proposed the establishment of a US-backed civil government and the revamp of the public school system.

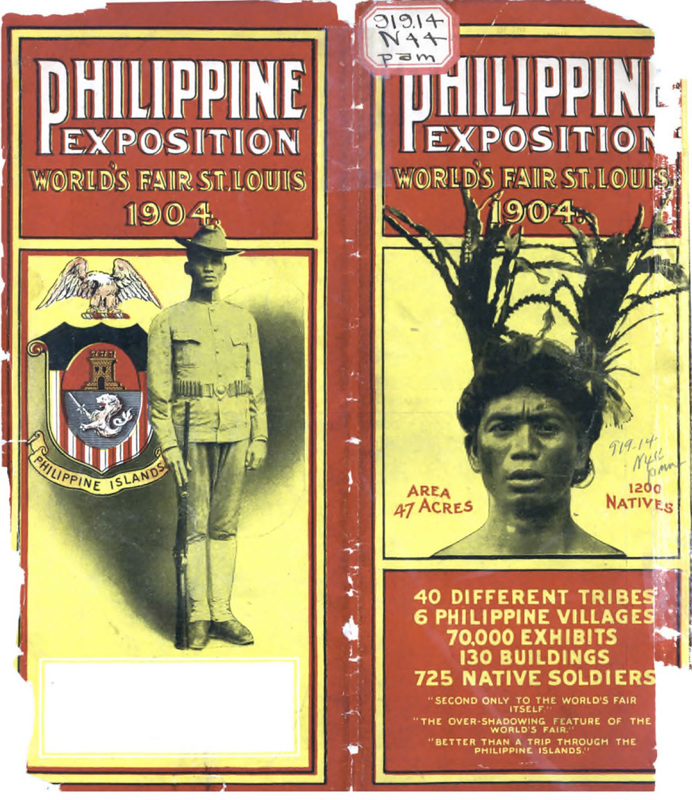

An important event in the first decade of the 20th century directly linked the Midwest with the Philippines. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, more popularly known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, was held in St Louis, Missouri in 1904. It was a combination of a trade show and a cultural exposition meant to exalt the newly acquired superpower status of the US.

One of the main highlights of the St. Louis World’s Fair was the so-called Philippine Exposition. Pictured on one side of the burnt orange brochure is a Filipino soldier in uniform, next to the Philippine coat of arms during the American period. It consists of an eagle as the crest and a shield bearing the castle of Spain on top and a sea lion beneath it, surmounted on a background of alternating red-and-white stripes representing the original 13 colonies of the US. The other side of the event brochure depicts a man from the northern Philippines wearing a feathered headpiece called dalisdis. The brochure advertises that attendees can see “40 different tribes, 6 Philippine villages, 70,000 exhibits, 130 buildings, 725 native soldiers.” Various people from the Philippines were flown in for the exposition; together with native peoples from other parts of Asia and America, they formed “the largest human zoo in world history”.

One of the “attractions” of the Philippine Exposition was a group of Filipino children who were made to sit in a model classroom while American fairgoers watched on from bleacher-like stands. It can be argued that the St Louis World’s Fair was translational if we define translation more capaciously as any form of mediation and movement between cultures. By showcasing the Filipino people and their customs in a performative display of indigeneity, the fair turned into an Orientalist spectacle of colonial life that interpreted the Philippines for the American public.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Breitbart, Eric. 1997. A World on Display: Photographs from the St. Louis World's Fair 1904. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Hawkins, Michael. 2020. Semi-Civilized: The Moro Village at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Silbey, David. 2007. A War of Frontier and Empire: The Philippine-American War, 1899-1902. New York: Hill and Wang.

Tan, Samuel K. 2002. The Filipino-American War, 1899-1913. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Rizal’s Noli and Fili

Resisting English