A Farewell to Arms: Ending the War and Negotiating the Treaty of Lausanne, 1922-1923

This page contains culturally sensitive or racist content and may be considered offensive to some viewers. The events are presented as a representation of cultural history for evaluation and critique. This is not an endorsement from the library but offered as a method to confront challenging histories associated with the objects through scholarship and discussion. Please use your discretion while exploring this page.

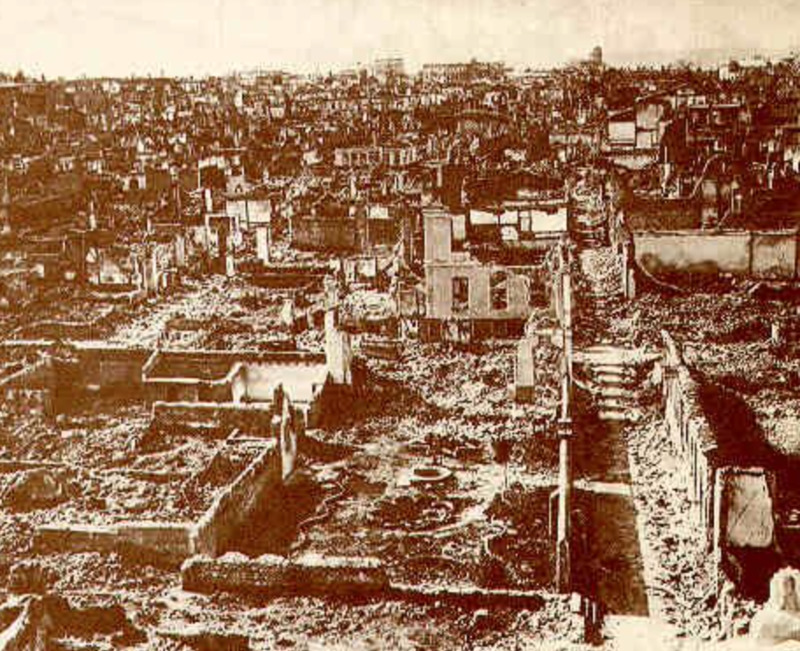

The burning of İzmir/Smyrna ended any large-scale battles between Greece and Turkey. With Turkey firmly in control of Anatolia, a treaty was drafted to put an end to the Greco-Turkish War. This agreement became known as the Treaty of Lausanne (signed in 1923, negotiations began in 1922), which solidified the borders of Greece and Turkey and enacted a forced transfer of about 1.6 million people between the two countries. This population exchange attempted to limit the reciprocal violence that was breaking out against Christians in Anatolia and Muslims in Thrace.

The Treaty of Lausanne, with some exception, created the borders of what became the Republic of Turkey in 1923. Unlike the Ottoman Empire, which had only been granted partial sovereignty by the European Powers, Turkey was granted full sovereignty. This may be why Turkey refers to the war as the Turkish War of Independence, among other names. The Treaty of Lausanne gave the country its western border, which spans Anatolia and two Aegean islands, Gökçeada/Imbros and Bozcaada/Tenedos. These islands are important for trade routes because they are close to the Çanakkale Boğazı/Dardanelles, a narrow strait in the eastern Aegean. Additionally, Turkey acquired Eastern Thrace, the region near İstanbul/Constantinople, which was heavily disputed during the war. Thrace is today split between Turkey to the east, Greece to the west, and Bulgaria to the north. Other agreements helped define Turkey’s southern border, which today comprises Iraq and Syria.

The treaty was quite specific about which people would be transferred between the two countries. Greece received the Ottoman Greeks, Armenians, and other Christian populations from Turkey. This caused its population to soar from 4.5 million to 5.7 million. These people often came from urban, artisan, and bourgeois backgrounds; this helped to create a unique refugee culture in Greece. Turkey received around 400,000 primarily agrarian Muslims. Since the Christian population leaving Turkey was much larger than the Muslim population arriving from Greece, Turkey’s population decreased significantly. Refugees in both countries faced issues with housing as they began their new lives. The language and cultural barriers of these forced refugees led to difficulties in assimilating into their new countries.

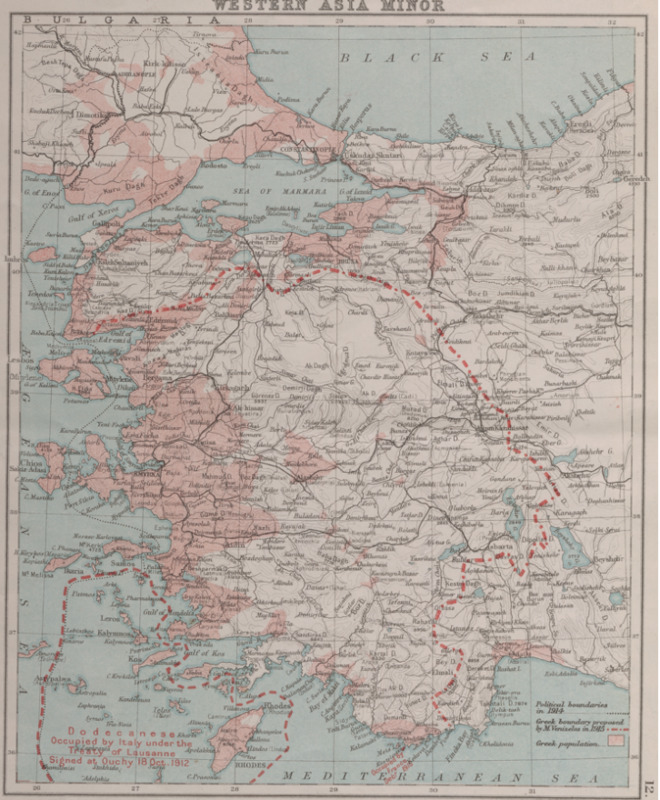

Western Anatolia, Eastern Thrace, and the Dodecanese islands are the geographical focus of this map, being in the center, upper left corner, and bottom left corner respectively. The Dodecanese is surrounded with a red dotted line to differentiate the Italian occupied territory from Turkish land. Another red dotted line cuts through half of Anatolia, representing Venizelos’ proposed Greek territory in 1915. Additionally, there are also sections of the map in pink that represent significant Greek populations. These pink clusters are primarily around the left side of the map, with the area surrounding İzmir/Smyrna being the most concentrated, as well as the coastline of Eastern Thrace.

The population exchange in the Treaty of Lausanne was designed as a means of reconciling cultural differences between different populations in Greece and Turkey. However, it is still an instance of what is now called ethnic cleansing. This is loosely defined as making a population ethnically homogeneous by removing undesired groups from the area. While this is not recognized as a crime under international law, its impact is not diminished. During the Greco-Turkish War, this was mainly accomplished by expelling Christian minorities from Turkey and Muslim minorities from Greece. It also took the form of genocide, especially in the case of the Armenian Genocide. The Turkish government has perpetuated false information about and even denial of the genocide. This remains a dark part of the country’s origin story, and public mentions of the event in Turkey are still often met with open hostility. In fact, the United States only officially recognized the genocide when President Biden acknowledged it in 2021. While not the focus of this exhibit, it is important to mention this event because it contributes to the emergence of modern Turkey and is another associated instance of ethnic cleansing.

The population exchange initiated by the Treaty of Lausanne had long-lasting effects on the countries and people involved. Muslims arriving in Turkey were expected to assimilate by speaking and identifying as Turkish. Christians arriving in Greece faced near-homelessness and xenophobia from their new neighbors. The minority populations that were not forced to relocate, such as the sizeable population of Ottoman Christians in İstanbul/Constantinople, faced open hostility before being forced out of the country as well. Many relocated people held out hope that one day they could return to their native land, but these dreams often went unfulfilled. Struggling to adapt to their new country, and yet made into foreigners in their old country, these people became perpetual refugees with no home to go back to.

Ashes to Ashes: The Greco-Turkish War and the Burning of İzmir/Smyrna, 1919-1922

Being a Refugee Twice: The Struggles of Greek and Turkish Expatriates, 1923-1929