The Death of a Dream: Developing a Modern Greek Identity

Although Venizelos and the Liberal Party made the decision to invade İzmir/Smyrna and to begin the Greco-Turkish War, the loss in the conflict is most often attributed to the Royalist Party. Greece held an election in 1920, which saw a power shift from the Liberal Party to the Royalist Party. The Royalists took control, and inherited the conflict from the Liberals. While the Royalists, led by Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, made the decisions that led to the Greek defeat, they were forced into that position by the Liberals. Therefore, realistically, both parties played a role in the disastrous end for the Greeks in the war. Because the Royalists were in power at the war’s conclusion, they took the blame. Fueled by public outrage at the Greek defeat, a military coup d’état erupted in Atina/Athens and the Aegean in September 1922. It is now known as the September 11th, 1922 Revolution, and was led by Venizelists against the Royalist Party and King Constantine. The king abdicated in favor of his son George, who installed a government favorable to the coup. King Constantine left for Sicily and never returned to Greece.

The scapegoating of the Royalist Party did not stop once the coup took control. In late 1922, nine members of the anti-Venizelist Royalist Party were tried for treason. Of these nine, six were executed by firing squad. The rest either faced life in prison or exile. One of those exiled was Prince Andrew, who was the father of Prince Phillip, the Duke of Edinburgh and the late husband of Queen Elizabeth II. Among the executed was then-Prime Minister Gounaris. In 2010, the Greek court ultimately reversed the decision and exonerated these six men after a descendant of one of the victims sought to clear his grandfather’s name. Nevertheless, some of the European powers were outspoken against these executions, and the United Kingdom even withdrew its ambassador to Greece for several years in protest. Although foreign powers protested the new regime, the coup government went ahead with the executions.

The ramifications of this scapegoating nonetheless haunted Greece for years. Politicians argued over how these six men should be remembered, if at all. Years after the war, the pro-Royalist press blasted Venizelos and the Liberals as murderers and criminals. Meanwhile, the incoming refugees from Turkey consistently voted for the Liberals, because they blamed the Royalists for the outcome of the war. This tension peaked in 1934, when Royalist George Vlachos proposed erecting a memorial temple for the six Royalists who had lost their lives in 1922. This, along with a proposed monument to King Constantine, who died in exile in 1923, caused outrage. The Royalists were accused of trying to capitalize on a national tragedy by making the monument a rallying point for their party. In essence, the 1920s and 1930s saw Greece trying to grapple with what they called the Asia Minor Catastrophe. On a wider scale, the Greeks saw the lost territory in Asia Minor as a loss of some of their homeland. It was a mourning process on a national level.

Memory by Stella Katergiannaki is a contemporary abstract painting. The lower half of the canvas is covered in flecks of gold clustered towards the center. The top of the painting depicts a sad child, whose face is painted in detail. The rest of the child is painted with random brushstrokes, obscuring some of the features.

The Greco-Turkish War had a profound influence on the development of Greece’s national identity. In only a few short years, the country went from the verge of becoming a powerful force in the Eastern Mediterranean to having all of those hopes dashed by defeat. The national narrative took a somber tone, mourning what could have been. At the same time, refugees from Turkey dealt with their own struggles, being suddenly expected to speak Greek and act like a Greek citizen. Many faced homelessness or lived in slums, and faced hostility from their native Greek neighbors. The experience of being expelled from their homeland was quite traumatic, and the refugees dealt with trauma for the remainder of their lives. In order to cope with this, many refugees channeled their grief in artistic ways. In the years after leaving Turkey, they wrote songs, poems, books, and created works of art. Over time, even these became adapted into the larger Greek narrative as well. Narratives changed over time, eventually painting a picture of Greek victimhood in the Greco-Turkish War, even if the Greeks were the initial invaders. These works of art and literature were not exclusive to the generation that migrated to Greece, and today people are still creating works of art that reflect on the conflict. The individual trauma of the original refugees has thus been adopted by the Greek nation as a whole, and gradually became a part of Greece’s cultural heritage over time.

The works produced by refugees in the years immediately following the Greco-Turkish War were more balanced reflections on their individual ordeal. As the years went on, the trauma narrative became more focused on a national perspective rather than the experiences of the individual. A pointed example of this is found in Elias Venezis’ book The Number 31328. His initial version was balanced, openly acknowledging wrongdoing on both sides. As he published new editions, a nationalistic perspective shows through that removes focus from the Greek army's negative conudcut during the war. The Greek telling of the Greco-Turkish War is often one of victimhood and mourning, particularly when it comes to refugees to Greece.

“...My old friend, stop a moment and think:

you’ll get used to it little by little.

Your nostalgia has created

a non-existent country, with laws

alien to earth and man.”

- Excerpt from “The Return of the Exile”, a 1938 poem by George Seferis, translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard.

This stanza from the poem “The Return of the Exile” by George Seferis encapsulates the national attitude of many Greek refugees. There was a profound sense of longing for what they had been forced to leave behind. In this poem, Seferis addresses this, asserting that the world that they were forced to leave behind no longer exists. This is true to some extent. The formerly Ottoman Greeks had lived in the Ottoman Empire, which was now the Republic of Turkey. The Ottoman Empire and, later, the Turkish government resettled Muslims in abandoned homes. Therefore, even if these refugees returned to their homelands, their homes might not be waiting for them. Although these traumatic events were specific to the refugee population, the same somber tones resonated with a wider Greek culture.

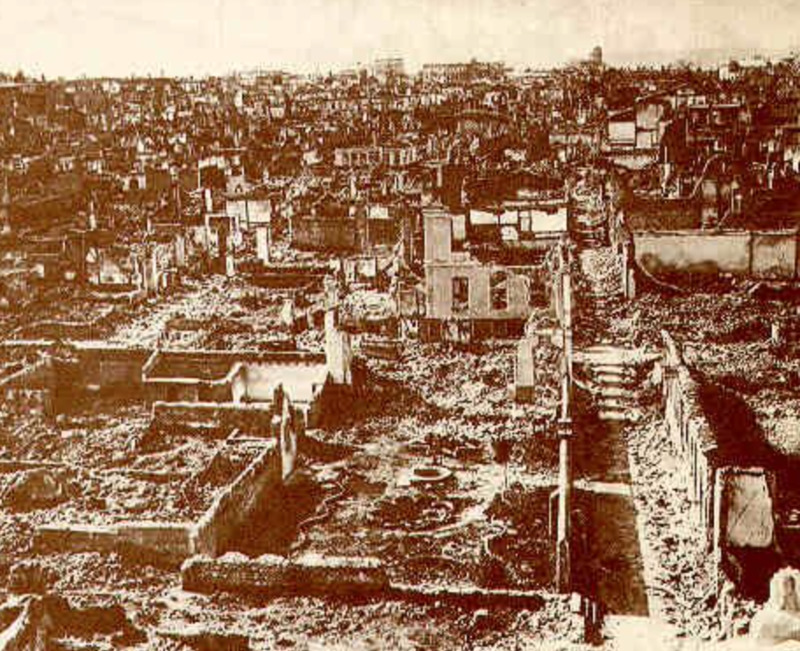

The painting Smyrna by contemporary Greek artist Evangelia Bolani depicts an idealized version of İzmir/Smyrna from a distance. The Aegean Sea is in the immediate foreground, and the city appears to be as it was before the fire started. The top right corner depicts the face of an old woman whose hair is covered by a black shawl. Her face rests on one of her hands, and tears stream down her face.

Greece as a nation also mourned the fall of the Megali Idea. The Treaty of Lausanne was the death knell for any ambitions in Anatolia, particularly in “reclaiming” İzmir/Smyrna and İstanbul/Constantinople. In a metaphorical sense, the Burning of İzmir/Smyrna was the burning of the Megali Idea. This is because the Greeks never claimed any part of Anatolia following the Greco-Turkish War. In modern times, no part of Anatolia had ever belonged to Greece, but their ancestors in Ancient and Byzantine times had lived there. Thus, there was a sense of ownership of the land, and many felt that they had been forced to give up part of their homeland.

Being a Refugee Twice: The Struggles of Greek and Turkish Expatriates, 1923-1929

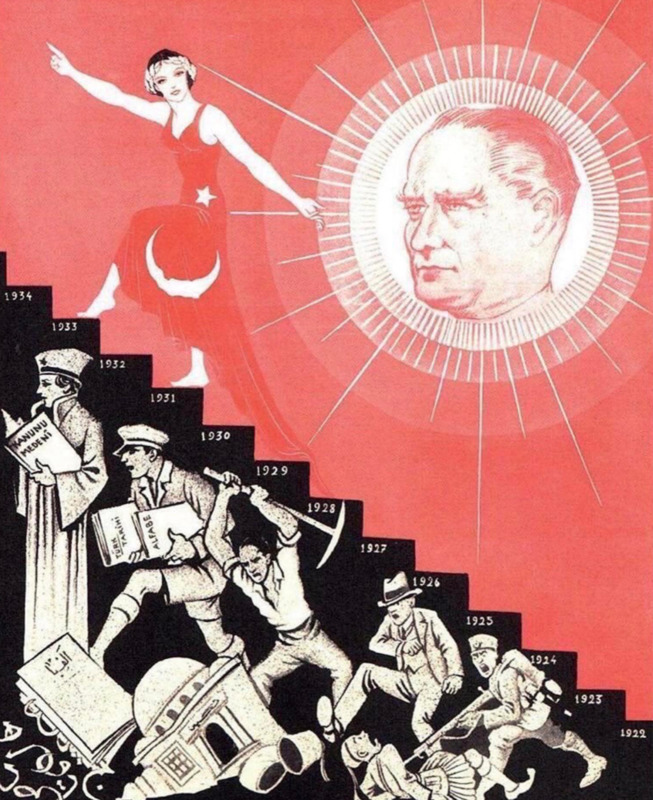

“Citizen, Speak Turkish!”: The Turkish National Identity and the Legacy of Mustafa Kemal