“Citizen, Speak Turkish!”: The Turkish National Identity and the Legacy of Mustafa Kemal

This page contains culturally sensitive or racist content and may be considered offensive to some viewers. The events are presented as a representation of cultural history for evaluation and critique. This is not an endorsement from the library but offered as a method to confront challenging histories associated with the objects through scholarship and discussion. Please use your discretion while exploring this page.

After the Turkish victories in the Greco-Turkish War, Mustafa Kemal needed to create new political and societal institutions for the new Republic of Turkey to survive while also separating it from the Ottoman Empire. Kemal outlawed religion from public life, abolished the Committee for Union and Progress, and eliminated the Sultanate. He accomplished this by utilizing Turkish nationalism, language, and education to create a new nation. Kemal’s innate focus on these ideological practices helped unify Turkey, but led to the dogmatic use of Kemal’s image and ideas by Kemalists.

One of the most important aspects of Turkish nation building in the early years was the “Citizen, Speak Turkish!” campaign that pressured non-Turks to speak the Turkish language in public. Furthermore, to be better in line with his own policy, Kemal stated that his own name was not the Arabic Kemal, but the Turkish Kamâl. Later in 1928 efforts were made to revise the Arabic script of Ottoman Turkish to have a better way to represent spoken Turkish. This mainly involved changing the Arabic script into the Latin script that is widely used today. Initially, the new Turkish script and language was difficult to read, even by those who spoke Turkish. Over time, the new script was adopted, and this increased the Turkish literacy rate. This campaign was a useful way of integrating peoples from different ethnicities into one Turkish identity. The state could neither utilize religion nor race for various reasons, and so speaking the Turkish language became of utmost importance to the regime.

Despite the Muslim majority and the recent expulsion of over one million Christians, Turkey was still populated by people of many different faiths. In an effort to modernize the country, Kemal did not establish Islam as the national religion. The state maintained an official policy of secularism. Kemal also initiated a number of other reforms designed to bring Turkey into the modern world, as well as to distance the country from its Ottoman roots.

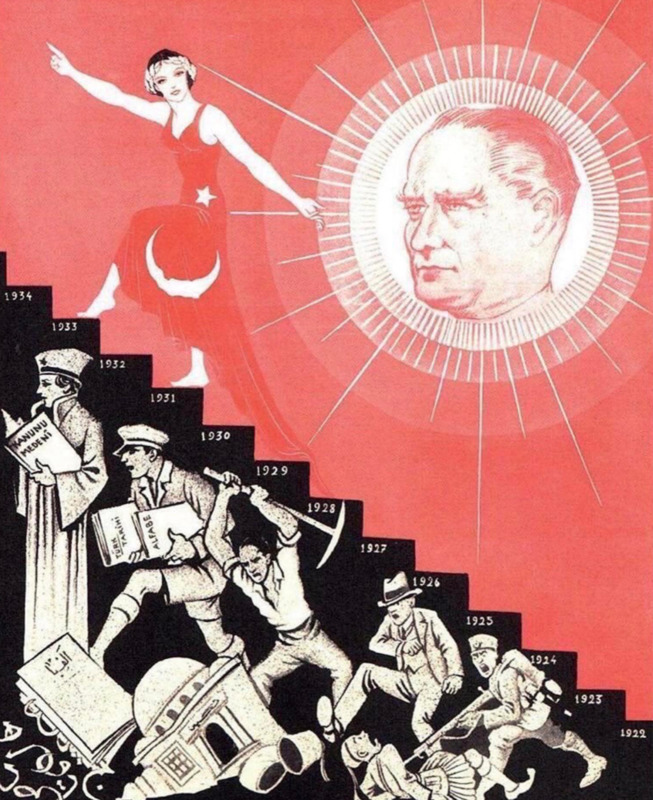

In the foreground of this propaganda poster from Kemalist Turkey, various figures are destroying remnants from the Ottoman Empire. These include a soldier pressing a gun against a Greek living in Anatolia and some men destroying a mosque. At the far left of the foreground, a man carries books and a woman is reading one. Above them is a staircase, with each step assigned a year from 1922-1934. A woman in a dress personified as Turkey is walking upwards as the almost haloed image of Mustafa Kemal looks on from the upper righthand corner. There is a stark contrast with the blackness beneath the staircase and the Turkish colors of red and white above it.

From 1923 to 1945, Turkey operated under a single party known as the Republican People’s Party. Any opposition party was crushed immediately during this time. These early years of Turkey were marked by rapid reform led by Kemal, the first president of Turkey from 1923 until his death in 1938. Kemal also adopted a number of policies to “modernize” the country such as banning the Fez – traditional Ottoman headwear – in 1925, mandating that Turkish citizens wear Western clothing, and requiring every citizen to take a surname in 1934. Kemal himself took the last name Atatürk, which translates to “father of the Turks”, and did not allow anyone else to take that surname. Even his children took different names. Turkey also enacted policies such as state feminism, which allowed women to vote and serve in the military. Atatürk’s adopted daughter Sabiha Gökçen became the first female combat pilot in the world as a result of these feminist policies.

Atatürk took extraordinary measures to solidify and maintain his grip on power. At a societal level, the Kurds, a majority Muslim ethnic group in Turkey and neighboring countries, resisted Kemalist Turkey the most. Like other non-Turks remaining in Anatolia, they were expected to now identify themselves as Turkish and speak the Turkish language. The Kurds desired independence, or at least the ability to self-govern under Turkish sovereignty. Beginning in 1919, Kurdish nationalists were rounded up and put to death for treason. In the early years of the regime, the Kurdish language was quickly banned in public. This also included the sole usage of Turkish in the courts, which placed the Kurds at a disadvantage in legal matters. The suppression of the Kurds resulted in the Shaykh Said Revolt in 1925. The Turkish government responded harshly, executing hundreds of rebels in the aftermath. It also took other actions to suppress this ethnic minority, such as forcibly relocating Kurds to prevent Kurdish majority populations in certain areas and bombing them. Gökçen participated in the bombings. As a result of this the Kurdish opposition was practically eradicated by the 1930s, although it would resurface in later decades.

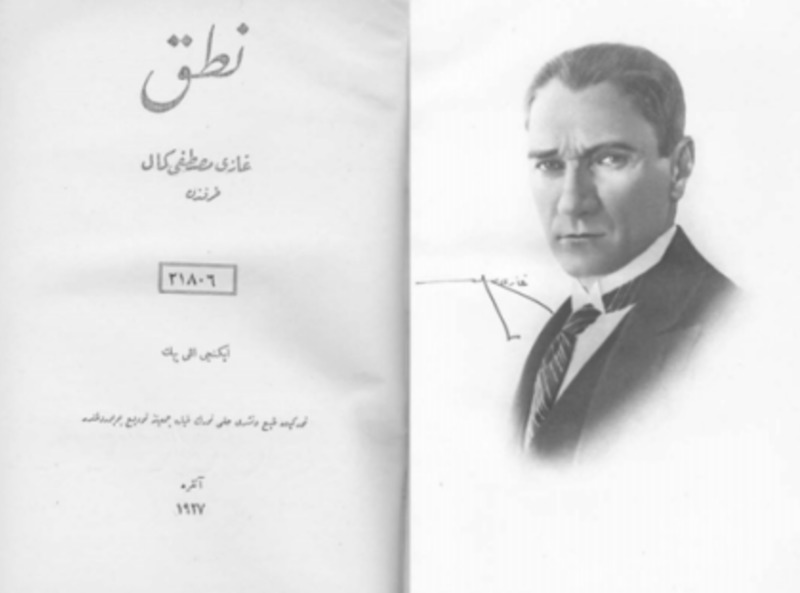

Atatürk also faced some opposition on the political front. In 1924, an opposition party formed to counter Atatürk’s Republican People’s Party. The new party called itself the Progressive Republican Party. It did not last long, however, as this party was eradicated by 1927, and was never officially recognized by the state. Atatürk used the Kurdish Revolts as an excuse to declare martial law, and he took the opportunity to suppress opposition parties like the Progressive Republican Party, as well as the independent press. By 1927, Atatürk had nearly solidified his place as the President of Turkey. It was around this time that Atatürk began drafting the Nutuk (also known as Büyük Nutuk), which is a famous speech he delivered over the course of six days in 1927. This speech established a tradition of Turkish historiography that is still prevalent in the country today.

The title page of the Nutuk speech has lettering in the old Arabic Script of Turkish on the left, containing the title and acknowledgements. On the right is a drawing of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk with a stern gaze and slicked back hair. Atatürk is also dressed in a Western fashion with a white collared shirt, black vest and blazer, and a striped tie.

The Nutuk asserted that in 1919, Turkey made a clean break from the Ottoman Empire, and became a separate entity. Additionally, Atatürk insisted that Turkey had fought in the Greco-Turkish War for the express purpose of creating an independent nation, which was not necessarily the case at the onset of the war. This speech provided the basis for Turkish history textbooks for decades, and is still associated with neo-nationalism in present day Turkey. It also invalidated the presence of non-Turks in Anatolia, contributing to the homogenization that transformed the country in its early years. This historiography also informed the government’s policy towards the Armenian Genocide, which to this day is one of denial and self-victimization.

In order to further push Turkification policies, Atatürk was also heavily involved in Turkey’s publication of academic literature, media, and the education system. Atatürk was a major contributor to the next generation of textbooks. Additionally, academic literature was vetted by Atatürk to ensure that they lined up with his beliefs and policies. The Kemalist control of Turkish media continued into the 1950s, and helped the government solidify a new Turkish identity. A key aspect of this new education was placing the Turkish people at the center of history. Atatürk helped perpetuate the belief that the Turkish steppe in Central Asia was the cradle of civilization. Atatürk even claimed that the first language ever spoken was Turkish. By taking such a macro view of the Turkish people, the Ottoman legacy became a footnote in the grand history of the Turks. This revisionist historiography became an obsession for Atatürk, and two months before his death he donated shares in a major Turkish bank to the Turkish Historical Organization.

As Atatürk’s ideas and policies continued to dominate the Turkish government, his status grew beyond that of a typical politician, leading to a mythical status. Statues of Atatürk were erected in cities, schools, parks, and public institutions that depicted him as the hero of the Greco-Turkish War and an unparalleled statesman. Additionally, the political parties in Turkey named themselves “Kemalists,” just as currency with the face of Atatürk circulated in the Turkish economy. Atatürk’s cult of personality had an undeniable gravity, and his focus on Turkification, secularism, and education dominated the Turkish political arena for decades. Atatürk’s legacy would outlive him. Following his death on November 10, 1938, Kemalists used his legacy to justify and defend their focus on Turkish nationalism and identity.

The Death of a Dream: Developing a Modern Greek Identity

The Legacies of the Greco-Turkish War