Being a Refugee Twice: The Struggles of Greek and Turkish Expatriates, 1923-1929

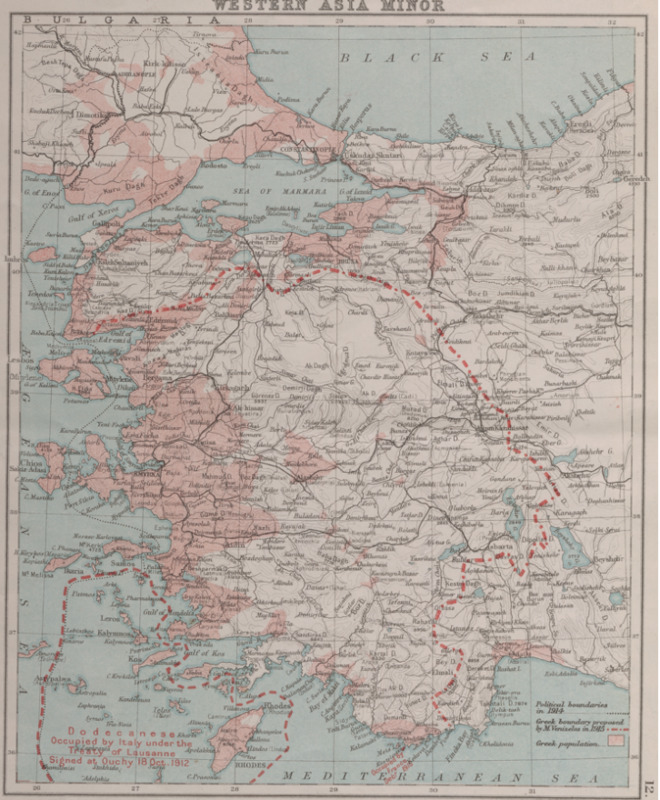

While the Treaty of Lausanne put an end to the Greco-Turkish War, it also unleashed an unanticipated humanitarian crisis in both Greece and Turkey. The foremost problems dealt with by the refugees were cultural assimilation in their new country and securing housing. Both Greece and Turkey expected these forced refugees to effortlessly blend into their countries. However, these people often did not speak the language of their new country, and were viewed as outsiders as a result. Furthermore, Greece and Turkey faced different logistical issues as their populations shifted significantly. Greece received a massive influx of new citizens while Turkey lost much of its bourgeois class and population as a whole.

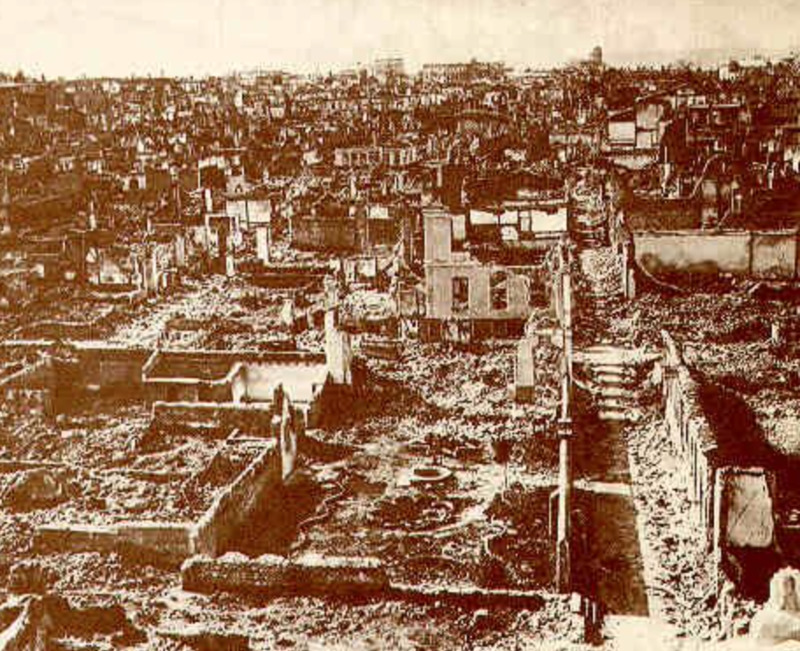

Following the Great Fire in 1922, İzmir/Smyrna lies in ruins. In this black and white photo, not a single building is untouched, and most are reduced to their foundations. This Western Anatolian city is one of many parts of Turkey in need of reconstruction following the Greco-Turkish War.

Forced refugees arrived in Turkey from Eastern Thrace, and primarily consisted of small scale agrarian families. However, as these new citizens settled around the country, they found that many of the houses and villages had been looted or occupied by the native Anatolians. This state of affairs did not lead to an amicable settlement, but it should be remembered that the preexisting Turkish population was struggling itself from the damage of the Greco-Turkish War. Entire cities, such as İzmir/Smyrna, were in dire need of repairs. While these agrarian families were largely self-sufficient after their settlement, they were not able to replace the economic value of the Anatolian Greeks, whom the Treaty of Lausanne forced out of Turkey.

Another issue was the language barrier, as many of the Thracian Turks arriving from Greece did not speak Turkish, further alienating them from the Anatolian Turks. The Kemalists in the Turkish government emphasized the importance of speaking Turkish, having several propaganda campaigns that tied being Turkish to the Turkish language. The Kemalist government reforms and focus on forging a national identity drove a stake between the refugees and the Anatolian Turks. Additionally, in 1928 and 1929 the Turkish script was reformed from its Arabic script to a Latin script that could better represent the Turkish language. This language reform would drastically increase the literacy rate of Turkey, but it took several campaigns by the Turkish government to achieve these results. However, as the language was complicated even for those who spoke Turkish, the newly arriving Turks from Greece who did not speak the Turkish language were disadvantaged and underrepresented in these educational programs.

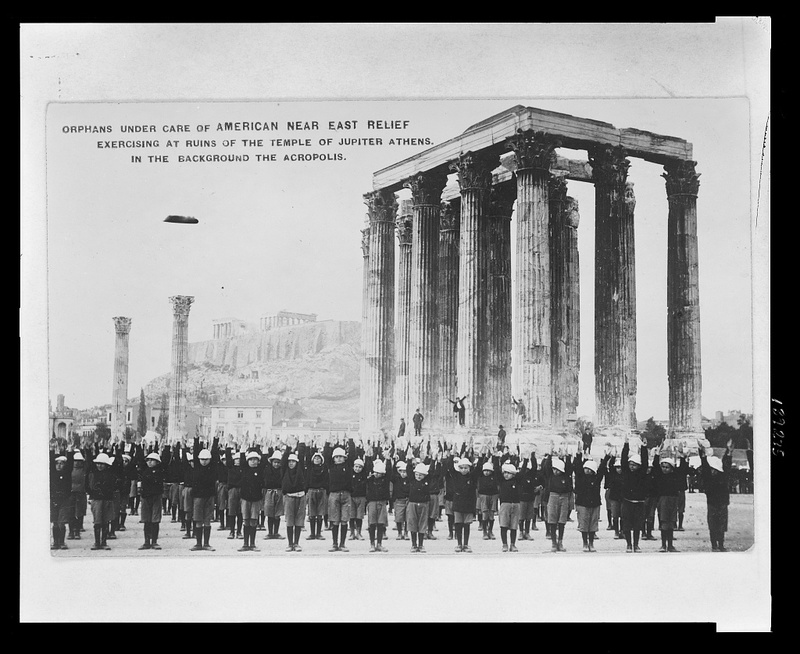

Orphans exercise in front of the ruins of the Temple of Jupiter in Atina/Athens on the front side of this postcard. In the foreground are dozens of identically dressed orphans exercising under the direction of the American Near East Relief. Directly behind the orphans is the Temple of Jupiter, and even further back in the distance are the Acropolis and the Parthenon. The towering ruins of ancient Greek culture dwarf the orphans in the foreground.

Christian refugees to Greece faced a similar set of difficulties as they struggled to adapt to their new lives. Large cities like Atina/Athens and Selanik/Thessaloniki were popular settlement sites for the newcomers. The political narratives surrounding the refugees to Greece and the reality of the refugee experience were quite different. While the government publicly welcomed these newcomers with open arms and allocated resources to help them begin their lives in Greece, the conditions of the refugees was less than ideal. These resources were often co-opted by native Greeks before the refugees even arrived. This meant that refugees were forced to face near-homelessness, occupying slums and living out of tents. The refugees’ new neighbors, who had lived in Greece for all or most of their lives, outwardly expressed xenophobia towards these refugees. They treated these newcomers as foreigners rather than as brethren, and were hostile to these people. Like the refugees to Turkey, these new Greeks struggled with practical issues like language barriers and the loss of all their economic capital.

The Greek government did not sit idly by as these newcomers entered their country. The Fund for Refugee Assistance was established in 1922, and it was designed to provide temporary relief for the new Greek citizens. The settlements designed by the fund became crowded with slums and shacks. Despite the Greek government’s best efforts, they did not have the resources to accommodate the large population increase. In Atina/Athens alone, the population jumped from around 450,000 in 1920 to about 1.1 million by 1940. The resources simply could not reach all of the refugees, which contributed to the crowding of shacks around these government-sponsored settlements. Entire neighborhoods made up of makeshift housing began to crop up in major cities. Even in the late 1920s, these refugees were forced to remain in these slums with little protection against the cold and wet Greek winters. Coupled with the pressure to adapt the Greek national identity, these people endured multitudes of hardship.

Not all Ottoman Christians were forced out of Turkey as a result of the Treaty of Lausanne. Populations in certain areas were exempted from the exchange. Ottoman Christians formed a sizable minority in İstanbul/Constantinople. Historically, the Western Europeans had used their presence in İstanbul/Constantinople to interfere in the city. Therefore, Turkish leaders hoped to get rid of the population in the Treaty of Lausanne negotiations. As other populations fled the country, around 110,000 Ottoman Christians remained in İstanbul/Constantinople. Greeks living on the islands of Gökçeada/Imbros and Bozcaada/Tenedos, which were given to Turkey in the Treaty of Lausanne, were also exempt from leaving. These populations did not necessarily fare better than their counterparts who were expelled to Greece. The Turkish government, due to its policy of ethnic homogenization, was not a favorable environment for non-Turks. They also faced open hostility even though they remained in their homeland. The number of Ottoman Christians in Turkey has decreased significantly over the years as a result of this treatment.

A number of Greeks had the opportunity to visit their homelands in Turkey over the years. Some were temporarily relocated to Turkey during World War II, where they briefly reunited with family in their old country. The Turkish government only permitted Muslims to stay, and so this reunion did not last long. Several Christians forced to relocate to Greece wrote accounts about visiting their childhood homes in the 1950s. One of these was Olga Vatidou, who spent her childhood in İzmir/Smyrna. The most striking observation in her account is that İzmir/Smyrna, which was once filled with prosperous Ottoman Greeks, was now a city filled with poor citizens. She, like others who also visited the city, felt that the world they had known as children had completely vanished. Decades of nation building had transformed the areas that these refugees had once lived in. This was a fact that many refugees grieved for the rest of their lives.

A Farewell to Arms: Ending the War and Negotiating the Treaty of Lausanne, 1922-1923

The Death of a Dream: Developing a Modern Greek Identity