Ashes to Ashes: The Greco-Turkish War and the Burning of İzmir/Smyrna, 1919-1922

This page contains culturally sensitive or racist content and may be considered offensive to some viewers. The events are presented as a representation of cultural history for evaluation and critique. This is not an endorsement from the library but offered as a method to confront challenging histories associated with the objects through scholarship and discussion. Please use your discretion while exploring this page.

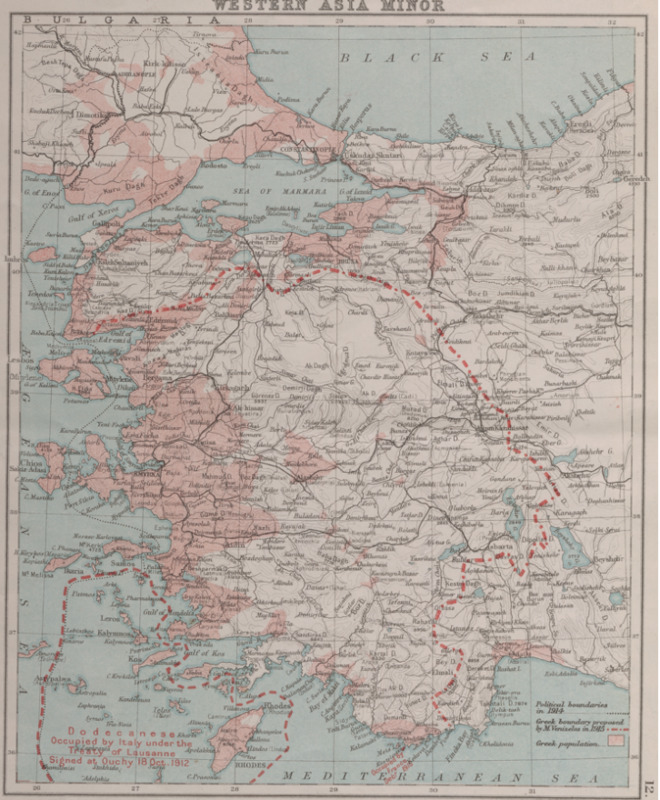

Greek forces provoked war by invading the city of İzmir/Smyrna on May 15, 1919. The Treaty of Sèvres stipulated that the Greeks would control the city for a period of five years, and they used this as a pretense for the invasion. This allowed them to do so with the blessing of the Entente Powers. The Greeks did not stop at İzmir/Smyrna and made swift progress into Anatolia in the early phases of the war. They also invaded Eastern Thrace (the region surrounding İstanbul/Constantinople) around the same time.

Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos was confident of Greek success with support from the western powers. Many saw Venizelos as a skilled foreign diplomat since he cultivated relationships with many world leaders. Venizelos’ close ties with European leaders were critical when the Greeks decided to invade Turkey. Diplomatic maneuvers such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 (an Anglo-French plan to split up the Ottoman Empire after its inevitable collapse) made it clear that the goals of Greece and those of the Entente Powers aligned. Even before the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres, European states maintained a presence in Anatolia. Some hoped to exercise some Christian influence in İstanbul/Constantinople, and were reluctant to leave the city. In fact, when the Greek invasion of İzmir/Smyrna began, France fought against Turkey to protect its sphere of influence in the Levant.

During a charge in the Ermos River, eight Greek infantrymen prepare for battle. Seven of these men look poised to attack, while the last man is crouched on the ground. All of these men wear soldiers’ uniforms and are heavily armed. The ground, possibly the bank of the river, appears muddy and barren.

By summer 1920, the Greek forces occupied a large portion of Western Anatolia. Some cities with a majority Greek or Christian populations actually greeted the Greek invaders as liberators. The Ottoman Empire had after all been a multicultural empire for centuries, and the idea of a majority Muslim Anatolia did not come to fruition until the population exchange following the Greco-Turkish War. The early phases of the war therefore held promise of Greek victory against the disjointed Turkish army. Unfortunately for the Greeks, this pattern would not hold for long.

The Greeks continued their offensive in 1921, encountering stiff resistance at the battle of İnönü. Though comparatively small in scale, İnönü proved that the Turkish armed forces could win against the Greeks, an idea that terrified the Western powers. The West’s lack of confidence in the Greek invasion prompted a meeting at the Conference of London, where the Western powers revised the Treaty of Sèvres and made it less severe against Turkey. France, Italy, and Britain ratified the revisions to the Treaty of Sèvres, lessening their direct involvement in the region. However, both Greece and Turkey refused to acknowledge these revisions. The Greeks believed they could not compromise and give up their advantageous position and Turkey viewed any revision of Sèvres that still ceded parts of Anatolia as unacceptable. Following this brief lull in combat, the Greeks attacked İnönü a second time on March 30, 1921, pushing back the Turkish army.

While the Turkish army had been pushed further east into Anatolia nearly the entire war, they had organized an orderly retreat and avoided any crippling defeats. Furthermore, as the Greeks advanced further into Anatolia their supply lines became strained, as Greek politicians called for further offensives. All of these processes came to a head at the battle of Sakarya, as the Greek army hit the final Turkish defensive line before Ankara. The battle of Sakarya raged for 21 days, from August 23 to September 13, 1921, and the Turkish defenses proved too much for the Greek army.

The next few months saw a tense stalemate form between the two armies, as the Greeks withdrew to a defensive position further west. However, the Western allies already agreed to a revision of Sèvres earlier in the year, and now began to withdraw their forces and support for Greece. Additionally, Venizelist supporters attempted a coup in Atina/Athens, but received no endorsement from Venizelos and were quickly dispersed. As the Greek forces became stagnant and divided, Turkey went on the offensive to retake its lost territory. This Turkish offensive led to the defeat of the Greeks army in August 1922, which resulted in a panicked retreat towards İzmir/Smyrna.

The Greek occupation had seen the looting of many Muslim communities, and several mass excecutions; a trend of violence continued by Turkish forces, who would perpetuate the same violence towards Christian communities. Most of the Greek forces and refugees retreated towards İzmir/Smyrna, creating a state of panic in the city. Western forces were unwilling to help evacuate the city, despite 21,000 British, French, and Italian nationals located in the city. As Turkish forces reached the city a fatal fire began in the old city, and the city of İzmir/Smyrna burned down, with the Armenian, Greek, and Frankish districts completely burned down.

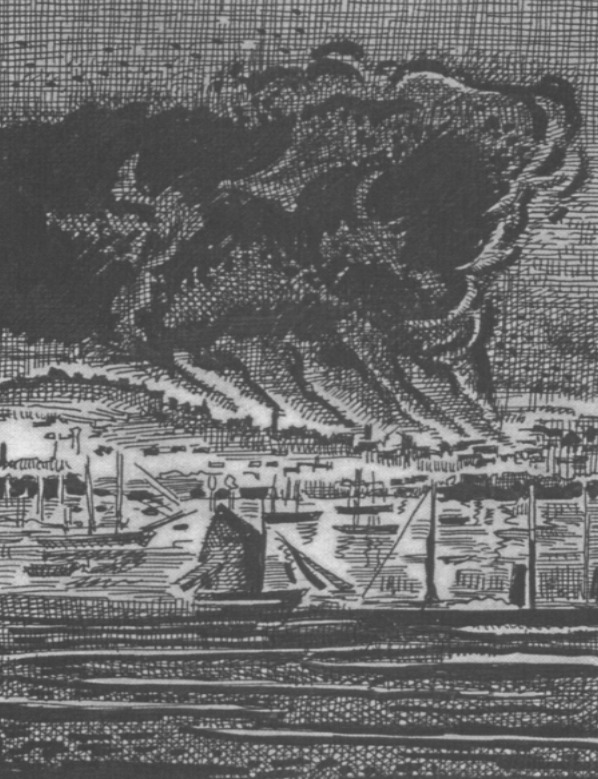

Large plumes of black smoke rise far above the city in this black and white drawing of the burning İzmir/Smyrna. The foreground has a variety of ships in the Aegean Sea, including, from left to right, a three masted sailing ship with a bowsprit, a small one-masted sailing vessel, and a warship with smokestacks. Smaller and lesser detailed ships dot the background of the drawing.

How the fire started is still a matter of great debate, with Greeks and Western authors vehemently claiming that it was started by the Turkish army, while the Turks state that Greek and Armenian forces began the fire as they retreated. However, the anti-Turkish biases of the first hand accounts, and Kemalist control over Turkish media following this period, make it difficult to determine how the fire began, or if it was even purposeful. The burning of İzmir/Smyrna ushered in an end to the conflict.

The War Before the War: World War I and the Treaty of Sèvres, 1830-1920

A Farewell to Arms: Ending the War and Negotiating the Treaty of Lausanne, 1922-1923