Collective Embroidery Practices

The kind of coordinated collective action that became a feature of the Belarusian protest requires a high level of organization. Among protest textiles, giant white-red-white flags are suitable examples. Such flags were first seen in Hrodna in the first week of the protests, and then in Minsk and the diasporas (15). Recent corpora of political embroidery are no exception. In the early phase of the protests, group embroidery was used to ensure the cohesion of the art community. A year later, similar projects continue to serve as an accessible and safe participatory practice, allowing individuals to work through their trauma. How many collective embroidery projects are known today? In addition to a series of workshops on craftivism by Pcholka and the “Tomorrow Is Every Day” collective, there are two more projects: 1.) A joint work by artists Daria Sazanovich and Yuliya Tsviatkova and 2.) collective embroidery presented by artist Vasilisa Palianina. In addition, one more group embroidery project is yet to be implemented: Rufina Bazlova in Prague plans to stitch together a quilt with portraits of political prisoners that would be embroidered collectively.

Pcholka is an artist, art manager and instructor. She started the VEHA initiative to preserve the visual history of Belarus. On 23 January 2021, the artist was detained in Minsk for picketing and left the country upon her release from jail. Since April 2021, Pcholka has been dividing her time among various art residencies abroad. Her textile work started with VEHA’s project titled Nailepchy bok [Best Side], a study of family photographs against woven backgrounds that was carried out through the lens of history, ethnography, and visual studies:

I was able to gain a better understanding of why women made rugs, why they chose certain ornaments, and what rituals accompanied their actions. Weaving was used for household items, interiors, and rituals. Embroidery was not as popular (which differs significantly from Ukraine, where embroidery rapidly became part of consumer culture and is a lot more popular than in Belarus). When women embroider, they communicate a lot, while weaving is primarily an individual, creative work. Therefore, it has less general information exchange, and more of a practical knowledge exchange [Pcholka 2021].

Pcholka's embroidery project Maiden Name (2018) was exhibited at the Krylia kholopa [Wings of a Serf] gallery in Brest as a part of the collective exhibition Mother Matter. It aims to restore the names of women, often several generations, living under one roof, but under different surnames:

When getting married, a woman traditionally assumes the husband's surname, thus respecting the new family. However, a change of the surname not only means a new status and symbolizes the rejection of a part of one's own life [Pcholka 2021].

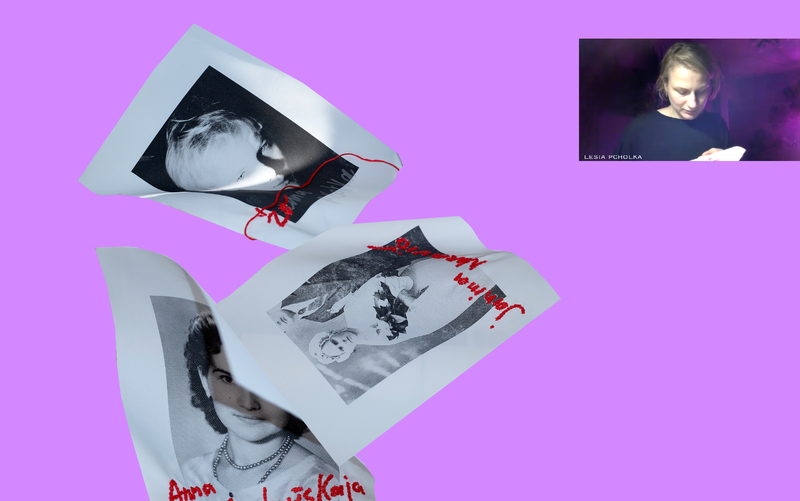

Pcholka's embroidery project Maiden Names' (2018) was exhibited at the Krylia kholopa [Wings of a Serf] gallery in Brest as a part of the collective exhibition Mother Matter. It aims to restore the names of women, often several generations living under one roof, but under different surnames. By embroidering women’s maiden names in red thread on their archival images, the artist reestablishes the lost genealogies.

By researching social memory and family photos, the artist noted that there was little information about women in response to this problem. She then decided to embroider their maiden names on archival images to reestablish these lost genealogies [Pcholka 2021]. The artist’s red thread and cross-stitch connects these names to traditional folk embroideries. Additionally, the cross symbol is reminiscent of how illiterate people used to sign their names before the Russian Revolution. According to the artist, the cross also symbolizes the glaring absence of family archives in many Belarusian families[Pcholka 2021].

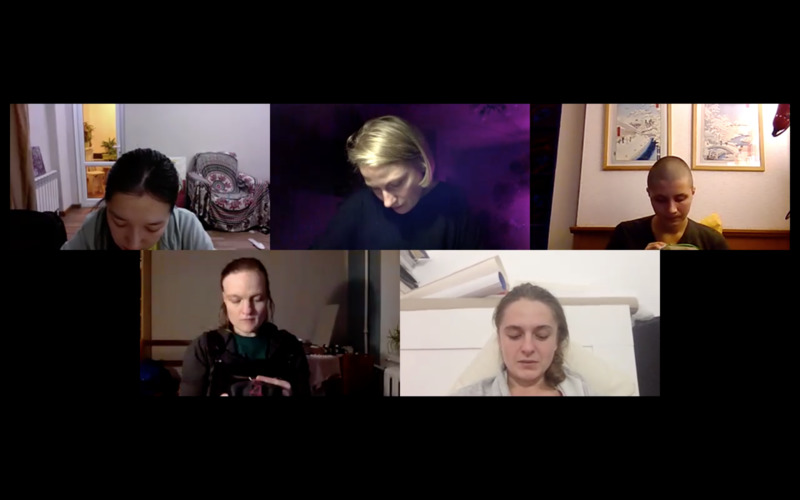

A screenshot from Embroidery Practices workshop conducted by Lesia Pcholka online and offline from 2020 onwards. While the process in these workshops is more important than the product, the communicative component of this ongoing group project amplifies the voices of the embroiderers from across the post-Soviet region and allows them to discuss pressing socio-political concerns.

Maiden Names became the starting point for a series of workshops that Pcholka conducted online and offline under the title Embroidery Practices. Directed against the patriarchal system, this workshop coincided with mass protests led by women in Belarus. As part of this event, participants embroidered and discussed critical social issues. This series is currently not in public view and remains a work-in-progress:

The work from Embroidery Practices is not online. In this series, the process and what the participants said is more important than the final product. Each of us embroidered something of our own, and together we talked about political and social problems. These meetings were not directly related to the protests [Pcholka 2021].

While organizing these events, the artist was aware of the historical link between radical activism and needlecrafts throughout the history of women's suffrage [Pcholka 2021]. According to Pcholka, the communicative component of this ongoing group project amplified the voices of the embroiderers. Another Belarusian project entitled Tomorrow is every day ran concurrently with Embroidery Practices. The famous Minsk Ў gallery launched this project in August 2020 and promoted it with #заЎтракожныдзень on social media. In the years from 2009 to 2020, this gallery became one of the country's leading platforms for promoting contemporary art. The collective embroidery project was one of the last in the gallery's existence. One of the gallery's co-founders, Sasha Vasilevich, was already in jail at the time.

The idea for Tomorrow is every day was created by artist and curator Marina Naprushkina, curator Lena Prenz (both Berlin-based), and the Minsk-based Anna Chistoserdova Valentina Kiselyova, the Ў Gallery’s co-founders. The gallery’s Facebook and Instagram announced the project as follows:

"We are continuing with #заЎтракожныдзень, a project that takes place in real-time! More than ten artists have proposed their sketches for the joint creation of the hand-made documentary embroidered canvas, and each of you can participate in its creation! Besides the fact that we will create a large work of art together, the process of embroidery represents an excellent therapy and meditation that helps us to live through and process everything that touches us" [Ў Gallery 2020].

It is noteworthy that although the traditional for some regions of Belarus red-white-black palette was used to create this collective artwork, the embroiderers used a variety of stitching techniques, not just the cross-stitch. Furthermore, the item description avoids the term craftivism altogether but highlights the project’s therapeutic component. As the hashtag's name suggests, there is no beginning or end when inside an event, and for it to succeed, the collective action must continue every day. This idea was later reused in the most prominent Belarusian political art exhibition in Mystetskyi Arsenal (26 March 26–6 June 2021, Kyiv, Ukraine), under the title Every Day. Art. Solidarity. Resistance. Even though the artists of its sketches preferred to stay anonymous, the exhibition curators felt that it was too risky to take this artwork out of the country. As of today, the artwork remains unfinished, safely stored in Belarus, waiting for its time in the daylight.

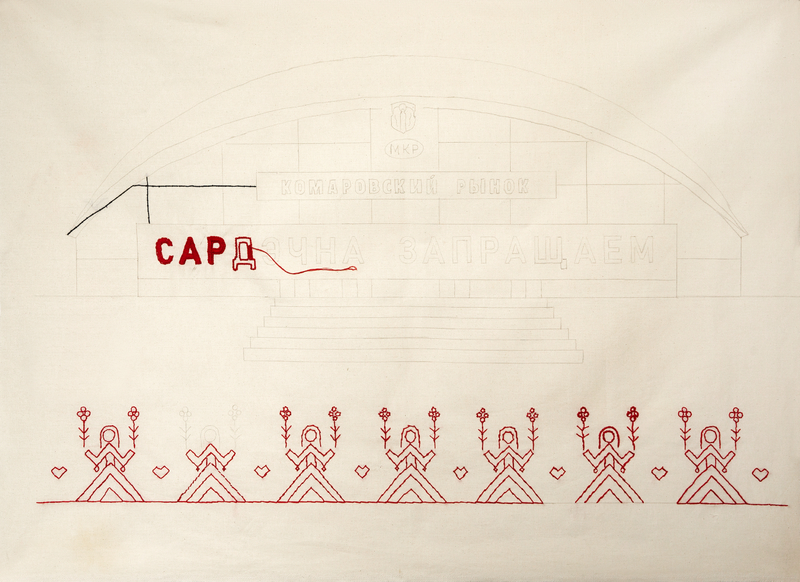

Tomorrow Is Every Day [#zaUtrakozhnydzen’] is an anonymous group needlework project started by the Ў Gallery of Contemporary Art in Minsk as a sort of communal art therapy project, where anyone was welcome to stop by and contribute. This closeup highlights the use of Belarus’s traditional embroidery material, linen and red thread, and Belarus’s women in white with flowers. The fragment depicts the Women in White’s very first action, when they appeared in front of the Kamarouskii market in Minsk on Aug. 12, 2020. The embroidered inscription says: “Kamarousky Market / Welcome.” Photographer: Viktoryia Kharytonava.

A second design from Tomorrow Is Every Day is based on an image of a choir singing God Almighty [Mahutny Bozha] on the steps of the National Philharmonic on Aug. 13, 2020, in protest against the police brutality of the preceding days. The lyrics were written by the poet, playwright, and translator Natallia Arseneva in 1943 and set to music by Mikola Ravenski in 1947, shortly thereafter becoming the anthem of the post-war Belarusian immigration. Arseneva was a displaced person who ended up in New York. Banned by the Lukashenka regime, her God Almighty is revered today as the country’s spiritual anthem. The embroidered inscription says: “My voice was stolen.” Photographer: Viktoryia Kharytonava.

ДЮ (DY) is a multimedia artist-duo of Belarus-born artists Daria Sazanovich and Yuliya Tsviatkova. The Zastolle project is a reflection and documentation of social and political processes in Belarus. The work refers to the traditional Slavic feast, which is “attended’’ by various representatives of the Belarusian society from repressed students to the police. Communication is represented in the form of visual symbols sewn into the fabric. The primitive crafts aesthetic of the textile piece resonates with a desperate state of inability to counteract violence. The Zastolle performance took place at the Bremen-based platform aRaum on September 23–29, 2021.

Sazanovich is an artist, designer, and illustrator, and Tsviatkova is a visual artist working in video and textiles. Both artists are from Belarus and live and work in Bremen, Germany. As the events in Belarus were unfolding, she would get together with her friend, artist Tsviatkova, to talk about the news and embroider stories that captured their attention. One such story is about how one of the protest leaders, Maria Kalesnikava, tore her passport when the regime tried to deport her in September 2020. According to Sazanovich, she does not frame her work as craftivism, even though she is familiar with this term. As a digital artist, she does not want to confine herself to a rather specific and narrow movement [Sazanovich 2021].

The inspiration for the project comes from the extracurricular art education she received as a child in her hometown of Babruysk:

"I always liked to do things with my own hands. From childhood, I went to all sorts of classes on handicrafts because my mother was the head of the after-school education program. So I ended up doing a lot of crafts with straw and the so-called 'applied arts'" [Sazanovich 2021].

And although Sazanovich’s embroidery does not visually reference the traditional canon, she feels a connection with folk culture not only via her training but also because one of her female ancestors was a folk whisperer. The artist is currently writing her master thesis on witches in modern culture entitled "How and why I would like to become a witch" [Sazanovich 2021].

This fragment of the Zastolle performance features some of the most recognizable symbols of the Belarusian protests of 2020. The torn passport is a direct reference to the brave action of Belarusian female political leader Maria Kolesnikova, who tore her passport after being kidnapped and taken to the Ukrainian border in September 2020. The blue hand is an allusion to a saying by Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenka, who famously quipped that he was not going to hold onto power with his blue fingers, a common side effect of a medical condition known as peripheral cyanosis.

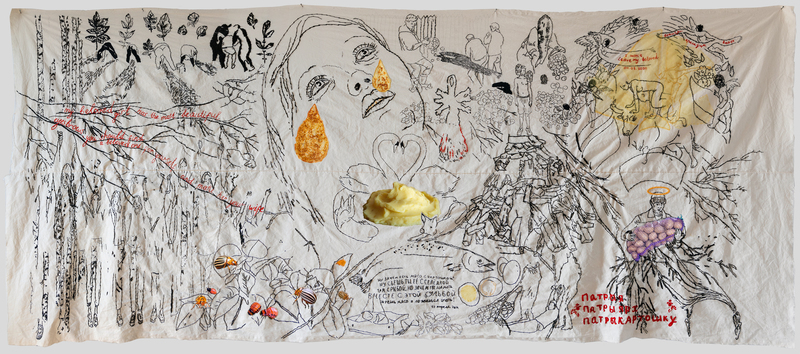

Whosoever Liveth and Believeth in Me Shall Never Die (2020-2021) is Vasilisa Palianina’s group embroidery project that was unveiled to the public at the exhibition When Shapes Become Shadows (2021), curated by Ilona Dergach. The exhibition took place in Krynki, Poland, on August 27, 2021. In the current political environment of Belarus, the medium of embroidery speaks to the advent of the collective female subject in the protest movement of Summer-Fall 2020. In this four-meter canvas, artist Vasilisa Palianina humorously explores the imaginary agrarian myth that holds that Belarus was born from the potato root and cultivated as the embodiment of the patient peasant class. The project's participants include the following individuals: Mariam Astryam, Sasha Dorskaya, Sashen Galerik, Kristina Brukshpyn, Polina Siriska, Katerina Ignashevich, Anna Kruk, Ulyana Dulkina, Tatiana Karpacheva, Masha Maroz, Ira J, Tasha Katsuba, and Aleksandra Osipovich. Curator Ilona Dergach describes collective embroidery labor as a form of group trance and psychotherapy.

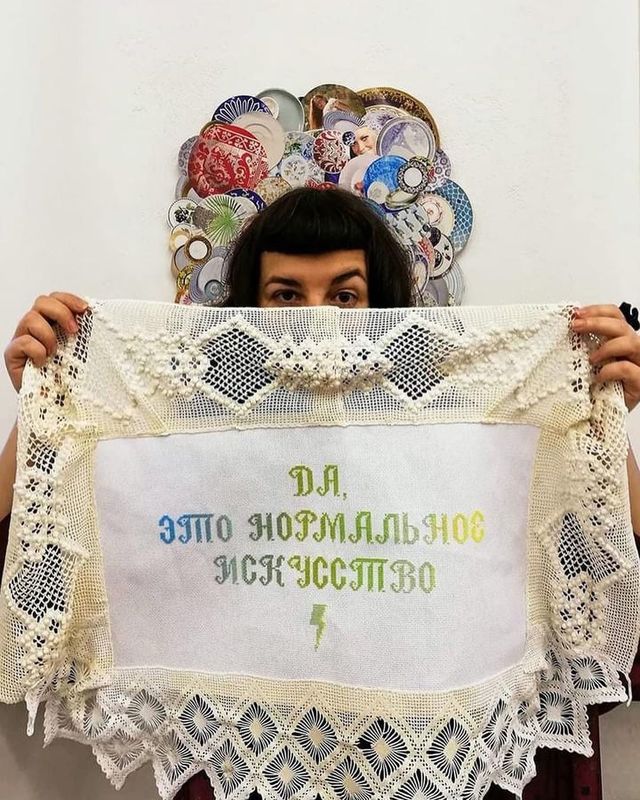

Vasilisa Palianina is a Belarusian artist who works across various media, including graphics, installation, performance, and experimental techniques. The artist’s connection to folk culture resides in the very idea of embroidery as a medium. Palianina made a name for herself for her work with sexuality and taboo. Since the beginning of the protests, these themes remained important to her, but they began to intertwine or were supplanted by reflection on the ongoing protests. According to the artist, “when the protests started, [her] degree of civic awareness and personal involvement in the development of [her] own country increased,” which resulted in a massive embroidered tableau she made in Minsk, with various artists stopping by her studio to participate [Palianina 2021]. When it comes to folklore, Palianina stressed that “heritage is a vital part of human culture. This is what forms our inner core, and its strength depends on how we relate to our heritage. Embroidery and textiles reference the origins of the folk language and are energetically compelling statements." The artist does not use the term craftivism but attests that her work can easily be situated within this movement [Palianina 2021].

Additionally, the artist emphasizes that the very medium of embroidery, because the process takes so long, provides the necessary distance for reflection, “What has happened to Belarusians and is happening now in the country is a critical and painful process of growing up, which will bear fruit in the future. While we are under so much stress, it is difficult to take a step back and assess the situation in an impartial manner" [Palianina 2021]. The same statement can be extrapolated to the entire protest embroidery corpus. Not all ideas have been implemented or completed, and not enough time has passed to evaluate these projects. At the same time, in the case of group embroidery, the process has a separate value from the product, and participation in it ignites a powerful mechanism of community recomposition. Therefore, it can be argued with a degree of caution that the participatory aspect of textile work and the very popularity of textiles as a medium in Belarusian folk tradition have become a peculiar feature of the Belarusian protest culture.

This particular embroidery fragment of Whosoever Liveth and Believeth in Me Shall Never Die (2020-2021) features the following Belarusian language inscription: “Patria, Patriarch, grate these potatoes,” –– exploring the homonymic similarity between the Belarusian verb pateret’ [to grate] with the Latinate variants of the noun patria.

Craftivist Strategies of Belarusian Protest Embroideries

Traditional Textile Patterns in Other Mediums