Craftivist Strategies of Belarusian Protest Embroideries

Can all protest embroidery created in Belarus be classified as craftivist, and what does craftivism have to do with this corpus? Craftivism was coined in 2003 by the American author Betsy Greer as a way to combine craft and activism. “Craftivism is a way of looking at life where voicing opinions through creativity makes your voice stronger, your compassion deeper & your quest for justice more infinite” [Greer 2007]. Her website encourages people to use their artistic talents in order to improve the world by expressing their opinions and supporting their causes. “Instead of being a number in a march or mass protest, craftivists apply their creativity toward making a difference one person at a time” [Greer 2007]. While craftivists use many different techniques, knitting and embroidery are among the most popular. In addition to addressing social and political matters, craftivists are closely linked with Third-wave feminist movements. In Belarus, awareness of craftivism rose from an article titled A cross-Stitch is not for an X [Krestik ne dlia krestika] [Kyky 2011] and several workshops hosted by Makeout, the LGBTQ platform, in 2017 and 2018. The well-known Ukrainian art group Shvemy organized a lecture on craftivism and a workshop focused on working with clothes, texts, and images during their 2017 visit to Minsk [Makeout 2017]. Additionally, Makeout held a workshop titled Free The Nipple [2018], which featured nipples embroidered on clothing. During the protest year, 2020–2021, Pcholka organized multiple craftivist workshops under the title Embroidery Practices. In February 2021 another craftivist event which included works by Belarusian artists was held, a workshop organized by a curator from Moldova, Sofia Tokar [2021]. At the same time, because the term itself did not gain a wide audience in Belarus, we can only discuss individual cases and strategies of craftivism. Artists born and raised both in Soviet and post-Soviet Belarus converge as they reimagine the traditional crafts that formed the core of their art education and follow the growing interest in fiber arts in international contemporary art.

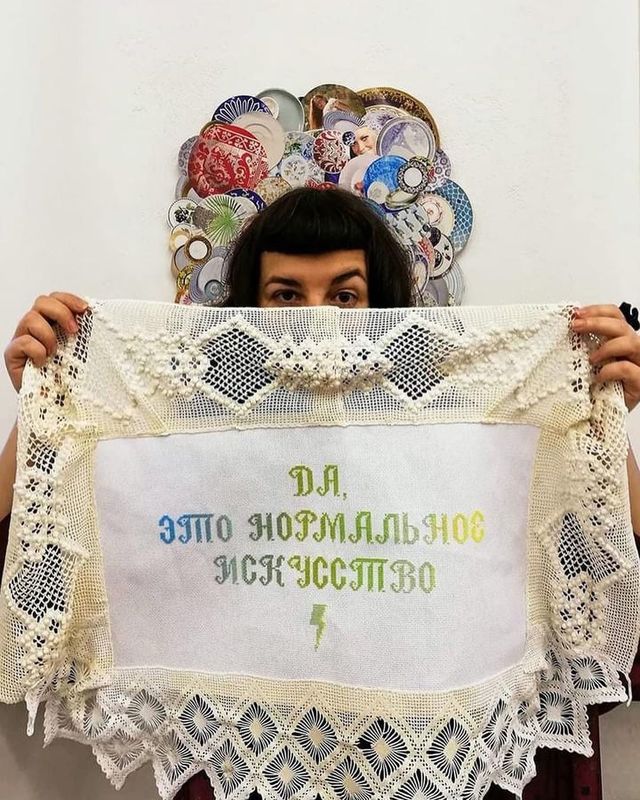

Anna Bundeleva is an artist and designer whose textile exhibitions, such as Action Postponed and Tabula rasa gained popularity in 2018. The artist considers textiles, fabric, and canvas as an untouched, tactile space and she chose this particular media due to its complexity and mobility and in spite of the stereotype that embroidery is a form of therapy or meditation, she enjoys its laborious, intense and concentrated nature [Bundeleva 2021]. Bundeleva did not design her two exhibitions in a craftivist vein, but instead avoided "framing [her] projects in isms," and was unaware of the craftivism movement until recently [Bundeleva 2021]. Meanwhile, the artist used craftivist strategies to reflect on the nature of art and its genre hierarchy, as in the work entitled Da, eto normal’noe iskusstvo [Yes, this is Normal Art] (2018).

An embroidered doily from Anna Bundeleva's exhibition Action Postponed, which took place at the 1+1=1 workshop led by Mikhail Gulin and Antonina Slobodchikova on May 26, 2018. She became one of the first Belarusian artists to turn to cross-stitch embroidery in her work.

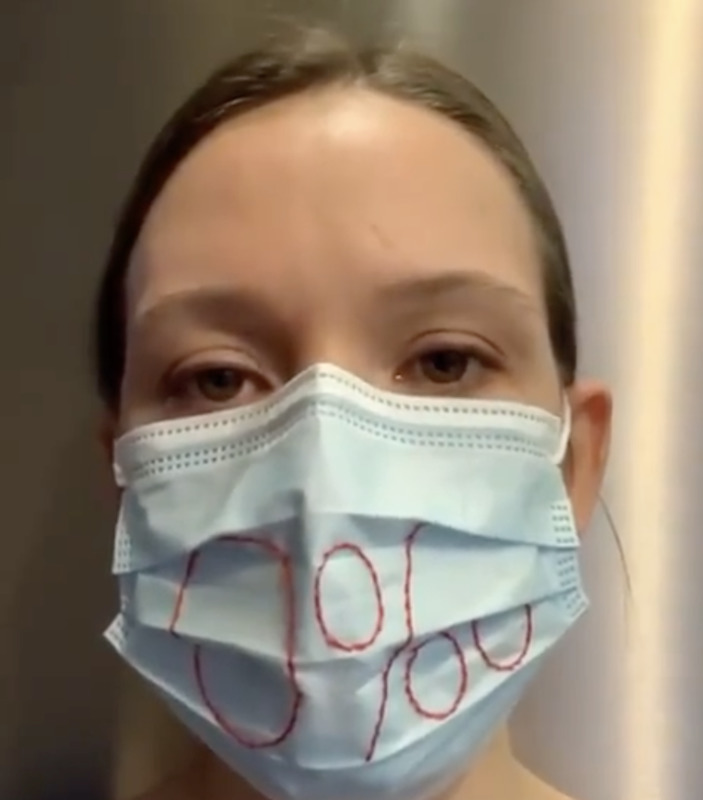

If Bundeleva's initial questioning of the genre hierarchy implied a socio-political connotation, then with the onset of the protests in Belarus, the artist began to make explicit political statements. Consider her embroidered tights for the Belarusian beauty queen and model Olga Khizhinkova, who was imprisoned for 42 days in November and December of 2020. Embroidering with white threads on black tights the phrase "I am/We are Khizhinkova" was Bundeleva's way of showing support. Among Bundeleva's other works, there is a video performance of embroidery on a medical mask in protest against the murder of Raman Bandarenka. The author removes three masks, each representing Bandarenka's blood as having zero percent alcohol: zero ppm, zero 0/000, and zero. It should also be noted that both works are posted in Bundelva's personal Instagram account, and are not in her creative portfolio. Therefore, they are perceived as a civil initiative. Her art, according to the artist, “has been on pause from the beginning of the protests” [Bundeleva 2021].

Olga Khizhinkova is a Belarusian beauty queen who was arrested at one of the women's marches in November 2020 and spent 42 days in prison. Belarusian retail spaces reacted to Khizhinkova’s arrest by covering her face on all packages of Conte tights, where she was featured as a model. Embroidering the phrase "I am/We are Khizhinkova" in white threads on black tights and posting it on Instagram was Bundeleva's way of showing support.

This is a screenshot from artist Anna Bundeleva’s performance. Wearing three medical masks, she removes two of them, displaying three different ways to say “zero percent”: Zero percent, Zero %, and 0%. "Zero percent" became another symbol of dissent in Belarus after the murder of Raman Bandarenka, a 31-year-old artist and teacher. On Nov. 12, 2020, Bandarenka was beaten and arrested in the courtyard of his home. He appeared in a hospital emergency room later that night, where he died the following day. According to official reports, Bandarenka got into a drunken brawl and was rescued by the police, who called for an ambulance. Bandarenka's emergency room doctor rejected this claim in an interview, stating his blood alcohol level was 0.0 percent.

In contrast to Bundeleva, who posits a clear distinction between explicit embroidered political statements and her art, our next artist, Varvara Sudnik, relies on craftivist strategies without separating her art from politics. In doing so, Sudnik's artworks combine folklore and craftivism, working with the theme of fear within a society traumatized by political repressions and massive human rights abuses. She began working with textiles in February 2021 after attending Sofia Tokar's craftivism workshop. Her work with textiles is described as follows:

"Aside from being fascinated by fabric, its creases, and tactility, I also appreciate the need to focus and slow down. It was the most accessible material to me, so I chose textiles first. As a medium for artwork, embroidery is still underrated, in my opinion. In spite of this, I have mastered it, and I appreciate the contribution of so many women who have and are still doing it, to the development of embroidery" [Sudnik 2021].

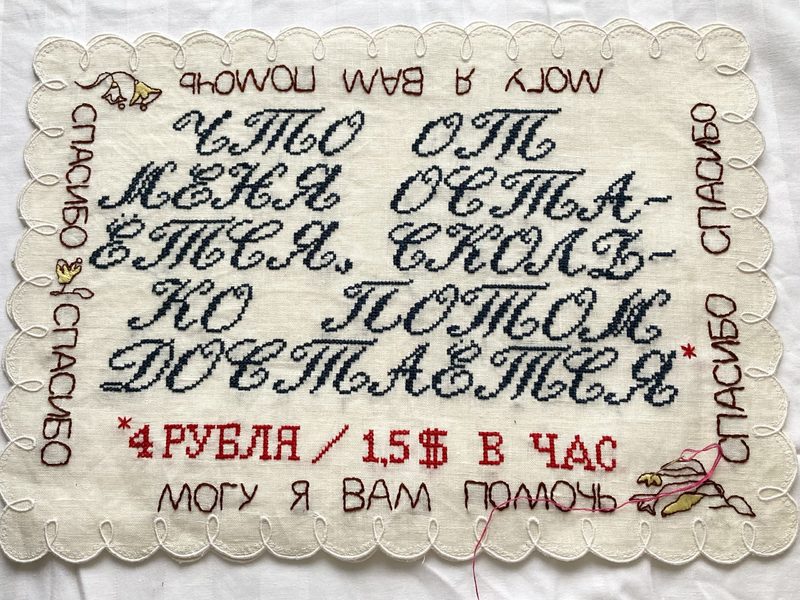

Sudnik, who generally adheres to a craftivist philosophy, is very cautious when it comes to political statements due to the harsh political climate in the country. In the artist’s work done outside of Belarus, e.g. her Work Shifts 2/2 series, she does not shun direct references to labor rights. She describes her embroidered doilies as "an expression of humility and acceptance of the status quo" [Soroka, Grebennikova, Sudnik and Mon 2021]. Produced in Belarus, Sudnik's latest work, however, is more introspective as it focuses on the domestic political situation through the theme of fear. The author interprets fear, an intense emotion that dominates civil society, as a child finger game ritual titled 'Koza rogataia' [Horned goat], embroidered on a Soviet-style miniduvet cover. Commenting on social fear through a text enjoyed by children in East Slavic and Russophone families, the artist estranges this emotion and reduces it to a game.

Work Shifts 2/2 (2021) series is dedicated to labor rights and the precarity of workers in Belarus. The artist describes her embroidered synthetic doilies as an expression of humility and acceptance of the status quo, underscored by the labor-intensive process of embroidery. The inscription on the doily translates as follows: “What will remain after I am gone, how much of it will go to me. 4 roubles/$1.5 an hour. Can I help you. Thank you Thank you.”

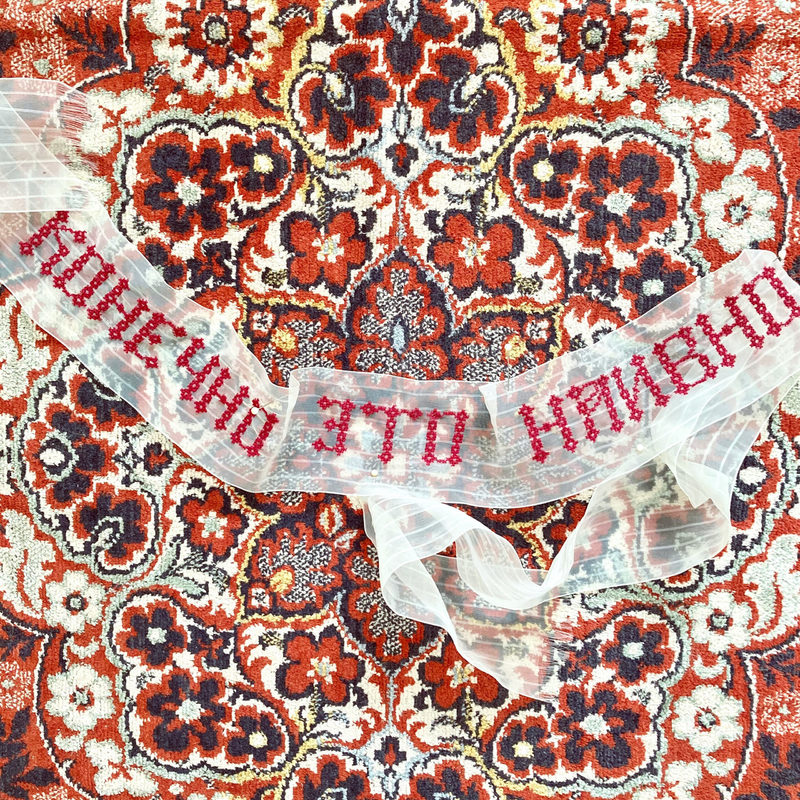

This duvet is cross-stitched with the words from a children’s tale about a goat who attacks misbehaving children. The text reads: “There is a horned goat who comes for the little ones: he butts, he butts and he butts.” Contemporary conditions in Belarus make it difficult to make political statements directly, and so craftivists carry it out allegorically, using examples from folklore.

Another work by Sudnik, a ribbon displayed against the backdrop of a rug, is familiar to generations of schoolchildren since Soviet times. The embroidered inscription “Of course, this is naive” can be read as programmatic for the artist, who describes herself as a “simpleton from a small town and a humble family background” [Soroka, Grebennikova, Sudnik and Mon 2021]. However, starting from 2020, Belarusians have also associated ribbons with protest rituals, namely makeshift flags made out of white and red ribbons. People tie them to fences to express their discontent and support the protests, and the artist's utterance here works on multiple levels, both as a marker of her provincial identity and as a critical statement about the protest tactics.

According to the artist, Belarusian folk heritage plays a crucial role in her work:

"Sometimes [folklore] scares me, like a dark forest, sometimes I feel like it is blooming inside of me. It takes hold of me and makes me breathless, enchants, and leads me. This connection is very profound. It gives me an understanding of who I am and how I channel the people who were here before me" [Sudnik 2021].

The embroidered message on a synthetic ribbon — Of course, this is naive — connotes several meanings, most obviously sifted from the anthropology of Soviet-era nostalgia, as reflected in the material of ribbon used by schoolgirls in Belarus and the use of the Soviet-era rug in the background. However, starting from 2020, Belarusians have also associated ribbons with protest rituals, namely makeshift flags made out of white and red ribbons. People tie them to fences to express their discontent with the regime and support the protest, and the artist's utterance here works on multiple levels, both as a marker of her provincial identity and as a critical statement about the protest tactics.

By contrast with Sudnik's contextual engagement with children's folklore, Minsk-based designer Nasta Vasiuchenka approaches Belarusian folk narratives in a more direct manner that utilize craftivist concepts. After receiving an art education at the Belarusian State Academy of Arts, Vasiuchenka became known in 2017 for a collection of clothes inspired by the Radziwill family and Baroque style mixed with streetwear designed for popular Belarusian label Mark Formelle [Belarus Fashion Week 2018]. Similarly, Vasiuchenka’s protest work combines casual style, minimalism and historical elements. Her Kanva label combines archival images of village women, straw earrings, necklaces and kerchiefs. During the protests, Vaijuchenka designed a T-shirt with the iconic inscription Flower Power embroidered with beads in national colors. In addition to its more recognizable allusion to the international pacifist slogan, this work references the specific protest action in the country. Vasiuchenka’s portfolio on Behance includes images from the Kamarouskii market, the site of the famous action of women in white that took place on 12 August 2020.

A hand-beaded shirt, inspired by the nonviolent protest actions of Belarusian women, references a slogan used during the late 1960s and early 1970s as a symbol of nonviolent action by the hippie subculture. In August 2020, flowers became a symbol of the peaceful protest in Belarus, while the location of the photoshoot, Kamarousky market in Minsk, is well-known as the site of the first massive protest actions organized and led by the Women in White Telegram channel.

If the artist’s T-shirts remediate an international pacifist slogan in a local context, then her embroidered scarves which she calls kupalki, or song-kerchiefs, are uniquely Belarusian products. According to Vasiuchenka, embroidered statements on kerchiefs appeared at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, as a result of the development of literacy and education among peasants [Vasiuchenka 2021]. Before designing kerchiefs with folk songs, the artist made another series with quotes from Belarusian prose writer Uladzimir Karatkevich. Among this dissident author's most prominent works is Kalasy pad siarpom tvaim [The Ear of Rye Under Thy Sickle] (1968)––a novel he wrote about the January Uprising of 1863-1864. A reference to the uprising reflects Vasiuchenka's commitment to bringing culture to the masses [Vasiuchenka 2021] by echoing the contemporary situation in Belarus.

The Ear of Rye Under Thy Sickle is a Kanva label series featuring quotes from Uladzimir Karatkevich, the preeminent Belarusian prose writer. The Ear of Rye Under Thy Sickle [Kalasy pad siarpom tvaim] (1968) is a novel narrating the events of the January Uprising of 1863-1864. The reference to the uprising reflects Vasiuchenka's commitment to bringing Belarusian culture to the masses by echoing the contemporary situation in Belarus. The kerchief inscription on the photograph says: “Every person carries their sky with themselves.”

Vasiuchenka's interest in folk heritage began in 2016, during her studies at the academy, where, in her words, "there were whole semesters and summer practices devoted to folk costumes,” [Vasiuchenka 2021]. Vasiuchenka explains that "our cultural code lives in folklore. Without our culture, we can't identify ourselves; we can't be a nation. So I strive to promote culture through costume, fashion and ethnic music” [Vasiuchenka 2021].

In addition, her song-kerchiefs are linked to August 2020's Speuny skhod [singing circle], an event at the Kupalausky theater in Minsk organized by Siarhei Douhushau exemplifying folklore in resistance:

"After Pavел Latushkо resigned from his position as the director of the Kupalausky theater, and the entire troupe followed him, I began gathering my Speuny skhod near the theater building. We met daily at noon to sing. This was when the [Belarusian State] Philharmonic, the orchestra, and the choir, came out on the streets, too, and this was a parallel process. I chose the song repertoire based on the mood and my feeling at the time. At first, we sang the summer songs that were lyrical, philosophical, and feminine. Then there were famous songs, such as “Oj rechanka rechanka,” because everyone knew them and sang with great pleasure. These gatherings lasted for nine days and ended with the riot police showing up on the last day of August" [Douhushau 2021].

Similarly to music, a healing aspect is integral to Vasиuchenka’s art as well. "As protests broke out, the level of anxiety in 'our swamp' drove me to explore new techniques and means of artistic expression. As a result, my clothes have taken on a therapeutic and meditative quality. Embroidery and handicraft help me calm my nervous system, relax, and process my emotions here and now" [Vasiuchenka 2021]. The artist did not know the term craftivism, but acknowledged that "if you accept a creative sublimation for craftivism, then this is exactly what [she] is doing in this difficult last year" [Vasiuchenka 2021].

Kupalki, embroidered kerchiefs from Nasta Vasiuchenka, are literally song-kerchiefs, a unique artistic fusion of dress and music folklore carried out in a minimalist key. Embroidered statements on kerchiefs appeared at the turn of the 20th century, as a result of the development of literacy and education among peasants. The embroidered inscription features a line from a traditional Belarusian folk song: “For the darkness of the night, my eyes are bright.”

Textiles in Belarusian Contemporary Art Before, During, and After the Protests

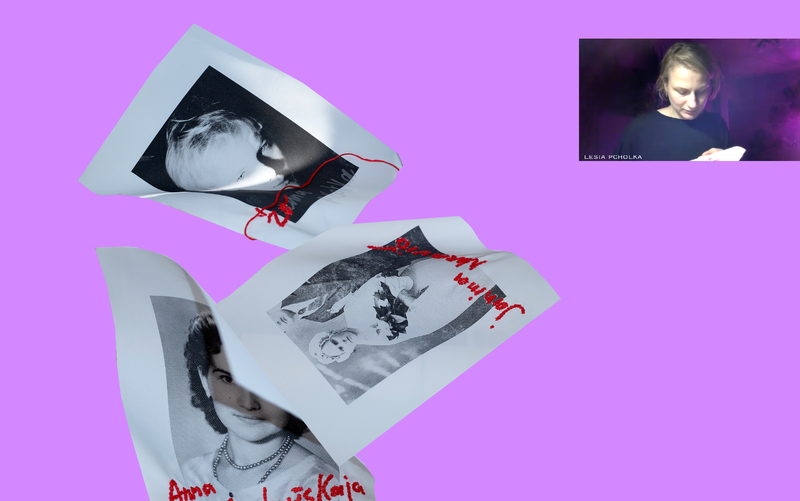

Collective Embroidery Practices