Traditional Textile Patterns in Other Mediums

By incorporating folklore, craftivism, after-school art education, formal art education and contemporary art practices, textile works explored various identities and meanings of the Belarusian protest culture. Symbolic representation of traditional textiles in other mediums exhibits the same dynamic. The works of Masha Maroz, Marina Naprushkina, Da(r)sha Golova, and Rufina Bazlova, illustrate the coexistence of different folds of Belarusian identity: from conventionally Soviet to searching for "authentic" folk roots and using folk motifs in cyber and art activism.

The following project looks at textiles and textile codes. Masha Maroz is a multimedia artist, designer and ethnographer from Minsk who works on collective memory and national identity topics. In 2014, Maroz graduated from the Belarusian State Academy of Arts with a degree in costume design. She is the founder and curator of Past Perfect, a platform dedicated to preserving and popularizing Belarusian historical and cultural heritage. Maroz describes her mission as “a mediator, a bridge, between the symbolic world of [the] ancestors and a modern world” [Polevikova and Maroz 2021]. She is especially inspired by Belarusian Polesia because her family comes from this region and she was born there as well [Dergach and Maroz 2020].

The Long Way Home, the artist’s first solo exhibition, took place on 26 June 2020, at the state-run Nekrasova 3, in Minsk. The exhibition content became the artist's protest against the the Lukashenka regime’s official narrative of Belarusianness:

"Today, many items associated with Belarusian culture—at least in the government’s official narrative—are imported directly from the Soviet era: straw dolls, vodka, and large, state-backed competitions and festivals celebrating everything from milkmaids to tractor drivers" [Polevikova and Maroz 2021].

Maroz, on the contrary, aims to experiment with “social, ideological, visual norms of modern Belarus for the preservation of folk culture" [2021]. Tradition, according to Maroz, is of central importance as a method of channeling information that is vital to society. By combining the handwoven rugs and an authentic Polesia interior with computer graphics, the artist closes the gap between the codes: the material of everyday culture and digital, through the ceremonial, multilayered space. The project installation represented an allusion to the interior of a traditional house in the Polesia region, reflecting not only on the visual component of folk culture but also presenting a sacred knowledge channeled into the attributes of interior decoration and the everyday, materializing the philosophy of home-creation and the organization of the living space.

Immediately after the presidential elections on August 9, 2020, Maroz took her exhibition down in a gesture of a protest against state violence [Derchach and Maroz 2020]. Earlier in July, the following digital work, featuring the traditional pattern of a female figure behind bars, appeared on her Instagram profile under the title Selfie-Time. Some images from this exhibition and those from the Past Perfect archive were later shown in the Netherlands as part of an exhibition titled Voices of Belarus. Chapter Two: Restoring Connections (on view at punt WG from 27 July to 1 August 2021, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Another recent exhibition to feature Maroz’s artwork from this series is When Forms Become Attitude, which opened on August 17 2021 in Krynki Gallery (Krynki, Poland), curated by Ilona Dergach.

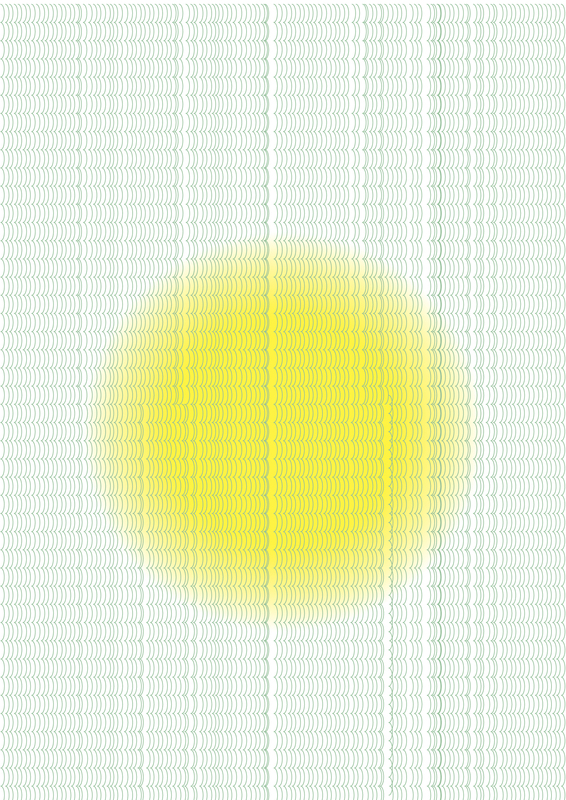

This digital artwork is part of a series of three images that form a group meditation and visualization exercise, part of Maroz's 2020 exhibition The Long Way Home at the National Center for Contemporary Arts in Minsk in June 2020. The participatory action invited people to come together in the gallery for an energy-cleansing ritual. The image depicts the sun juxtaposed against a digital textile grid. The title, The Sun Will Shine In Our Window, is a reference to a Belarusian publishing group that existed in Saint Petersburg, Russia, from 1906 to 1916. The title of the exhibition, The Long Way Home, alludes to the memoirs of prominent Belarusian writer Vasil Bykau (1924–2003).

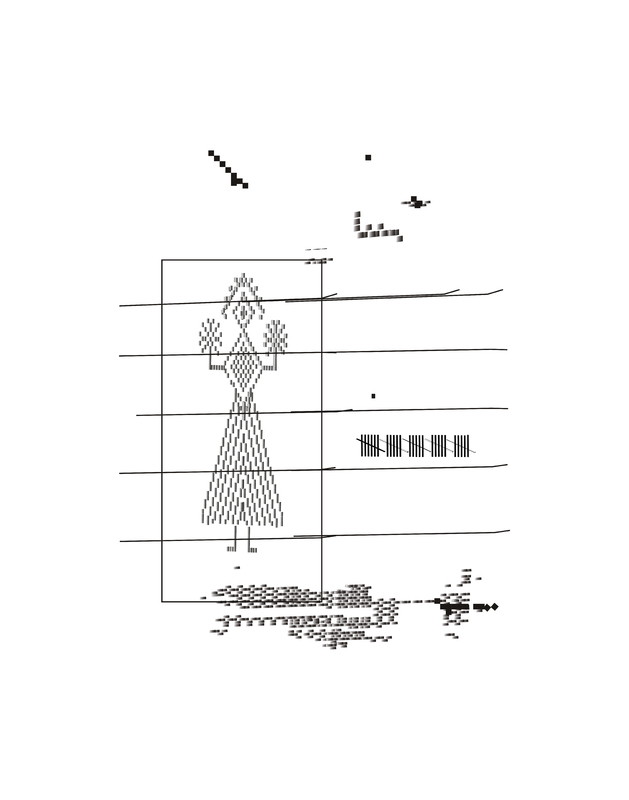

This digital artwork was part of Maroz’s 2020 exhibition The Long Way Home at the National Center for Contemporary Arts in Minsk, which focused on the influence of social and ideological norms of modern Belarus and specifically the heritage of traditional Belarusian culture and collective memory. The image represents a woman caught up in a digital grid of what appear to be jail bars, while the marks on the right represent the common counting practice of sets of fives.

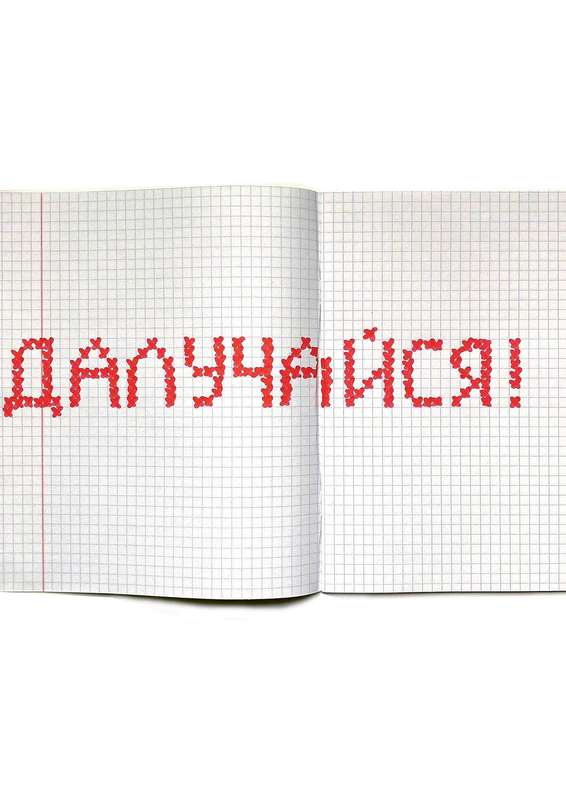

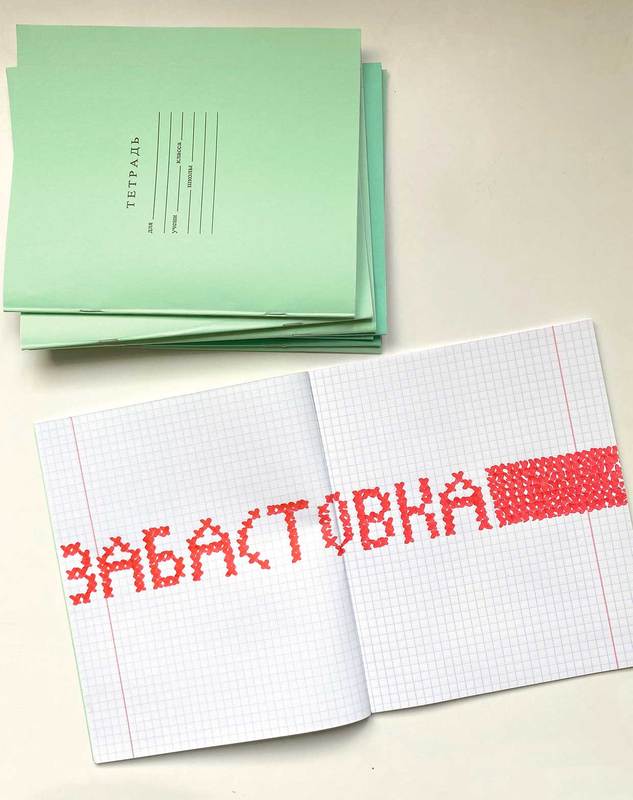

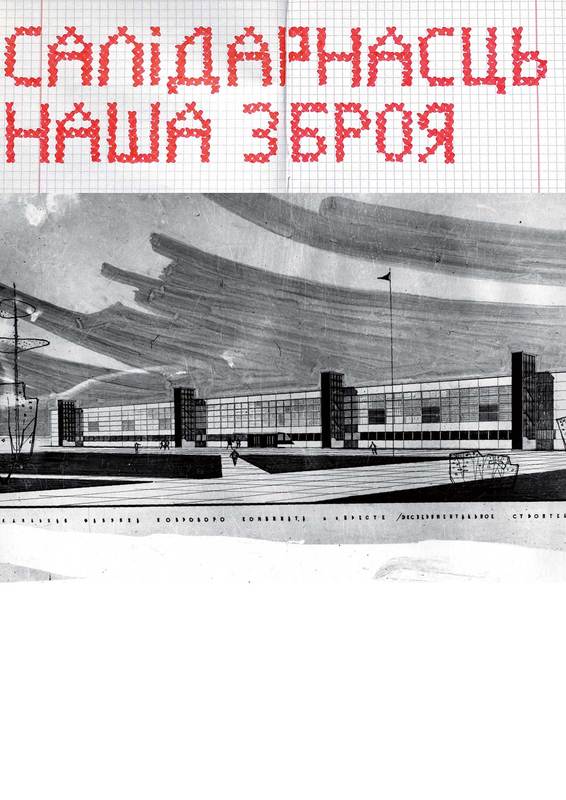

Naprushkina is a Belarusian-German feminist artist and activist who works with video, performance, drawings, installations, and text. From August to September 2020, Naprushkina was in Minsk, where she launched Tomorrow Is Every Day at Ў Gallery. Additionally, she created a series of posters referencing embroidery on school notebooks, writing her slogans in Belarusian with a red felt tip pen: Strike! Solidarity is Our Weapon. As soon as the works were completed, they were posted on Facebook, on the artist's page and deposited in the protest art archive cultprotest.me. They were also displayed in two exhibitions: A Secret Museum of the Workers Movement hosted by Hoast art gallery (on view 27 February to3 March 2021, Vienna, Austria) and Every Day. Art. Solidarity. Resistance at Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv, Ukraine. This is how the artist explains her work:

"I am showing exercise books that I also used when I was a child. These are the official school notebooks. And I chose some slogans from the street, which I heard in Belarus in August and September last year, and combined them with images from factory buildings. My grandfather was an architect, and he built a lot of factories in Belarus. The workers’ strikes were one of the most important parts of the protests. For me, it was also personal because I knew these very buildings from my grandfather’s drawings. The slogans also gesture at the cross-stitch embroidery technique, which alludes to female work" [Naprushkina 2021].

Solidarity is Our Weapon includes a drawing of a carpet factory in Brest built in 1958-1960 that serves as a reference to the country's textile industry. School notebooks and Soviet-era factories are symbols of Belarusian identity of the Soviet era and industrial labor as opposed to the artisanal pre-revolutionary production modality.

Join us! [Daluchaisia!], part of a series called Exercise Books, in which the author has drawn slogans of the resistance in school notebooks with felt-tip pens in the style of cross stitch, thereby inscribing the 2020 protests into Belarusian history.

Strike [Zabastovka] is part of a series called Exercise Books. It alludes to the all-national strike announced on August 11, 2020.

Solidarity is Our Weapon [Salidarnast nasha zbroia] is part of a series called Exercise Books. It juxtaposes letters drawn in red felt tip pen up against the background of a reprographic architectural drawing of a factory by the artist’s grandfather, who was a Soviet-era architect.

Postcards of Solidarity is an ongoing project developed by Amsterdam-based artist and designer Da(r)sha Golova (in collaboration withMaroz and Artemiy Sei). Similarly to Maroz’s “Long Road Home,” it also deals with the question of Belarusian identity. The exhibition’s introductory text states that political problems in modern Belarus are directly related to the destruction of the Belarusian ethnic heritage:

"The majority of Belarusians don't know their roots, culture and are ashamed of the Belarusian language, considering it 'peasant-like.' That is one of the reasons why we, as Belarusians, have been asleep as a nation for a long time and are now seeking the process of building and forging a new structure between us as humans, repairing connections between the land and people" [Maroz, Kulak, and Golova 2021].

Golova’s ambitious mail art project features 555 postcards from European cities with traditional textile patterns from Polesia printed across them. The patterns come from Maroz’s Past Perfect archive. According to the artists, such superimposition of West-European and Polesian images advance the “reparation of liaisons within the family, the reconnaissance of ornamental language, the visualization of the heritage that was never accessible to us, the remembrance of the names of ancestors to restore the way home” [2021]. Each of these cards is addressed to a different political prisoner in Belarus. The creators view these postcards as fragments of a broader message, an ornamental code of Belarusian tapestry and embroidery [2021]. All elements of this project contain crucial information, such as the recipient's name and address, the stamp, the ornament and the place of departure. “Everything is ready for you to activate this––not necessarily verbal––communication by picking one of them and dropping it into the postbox. By doing so, you are delivering hope, a cheerful gesture of awareness, acknowledgment, and support”[2021]. There is, however, a functional drawback to the project: exhibition visitors often sign these postcards in foreign languages, and they get through prison censors at random.

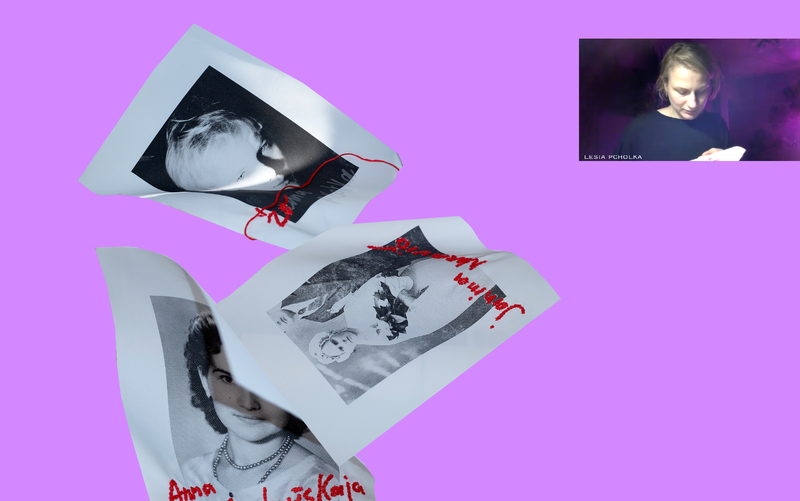

A scanned selection of postcards destined for Belarusian political prisoners. The project was presented at a number of venues in the Netherlands. The first edition of 260 cards for the Postcards of Solidarity project were made together with Masha Maroz and Artemiy Sei, at the group show Voices Of Belarus at the Glass Pavilion in Amsterdam, April 2021. The second edition of 555 cards for the Postcards of Solidarity project were made with Masha Maroz and Sasha Kulak, at the group show Voices of Belarus. Chapter Two: Restoring Connections at Punt WG, Amsterdam, July 2021 (photographer Sasha Kulak).

The second edition of 555 cards for the Postcards of Solidarity were made with Masha Maroz and Sasha Kulak, at the group show Voices of Belarus. Chapter Two: Restoring Connections at Punt WG, Amsterdam, July 2021 (photographer Sasha Kulak). Image from the opening event with enchanting music performance by Fuensanta Méndez.

If Golova’s Solidarity Postcards employ textile ornaments to confuse censors and convey a fragmented message, Bazlova’s art, on the contrary, is as readable as a comic strip. Bazlova, an illustrator, performer, and puppet master also uses the code of traditional textiles, but combines it with figurative elements, documenting the ongoing events in the country via her Instagram account. She began her History of Belarusian Vyzhyvanka cycle on a night of protests when the country was experiencing an internet blackout and used vector graphics to ensure fast production. Her images went viral on Instagram within days and appeared in several major newspapers. Each tableau of the cycle corresponds to an actual event during the Summer–Winter of 2020. Vyzhyvanka is a pun combining two Belarusian words, “embroidery” and “survival.” Vyshyvanka means “embroidered shirt.” Vyzhyvats' means “to survive.”

A year later, Bazlova’s work appeared in many exhibitions and on the covers of several journals and magazines. Besides her vector graphics, Bazlova produced physical embroidery and serigraphs. Even though the artist identifies with the craftivist movement and cyberactivism, her choice of medium, however, is inspired by her family tradition:

"My grandmother was a jack, or jill (!), of all trades: she sewed, knitted, weaved, and did macramé. My mother could do a little less, and the only thing that I was left with is embroidery" [Bazlova 2021].

Additionally, Bazlova used embroidery during her training as an artist and recognizes its importance in the traditional culture:

"For a long time, women were taught to neither read nor write. I learned that embroidery could be read as a kind of text. Everything they saw was reflected in their embroideries, which became their form of expression. My white and red motifs come from our folk culture. After all, the events that are taking place now, can be seen as the formation of the nation. And when such a powerful historical and cultural code depicts current events, it makes an impression on people" [Bazlova 2021.].

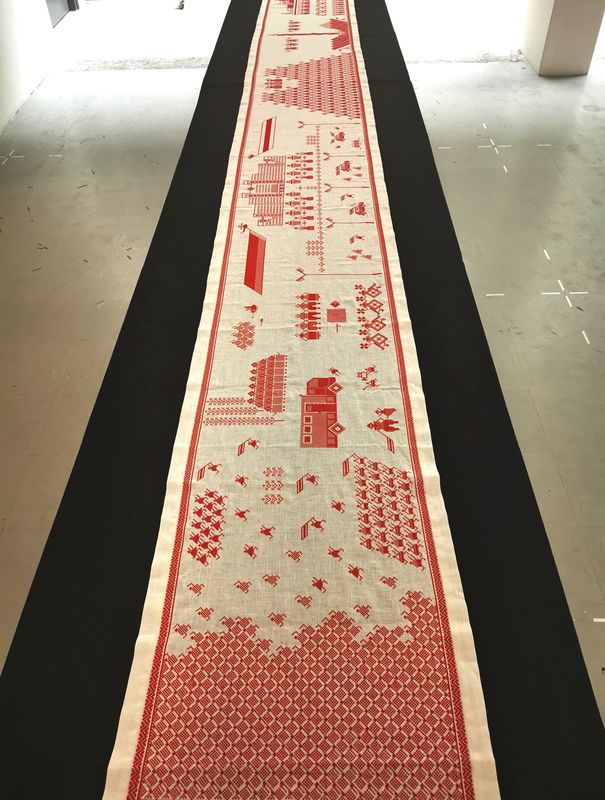

On the one hand, Bazlova speaks about “nation” and “people’s art” and is set to create “an embroidered epic of the Belarusian Revolution, in which each tableau corresponds to an episode of its recent history” [Bazlova 2021]. But she also engages with the narratives of cyber-feminism opposing state violence, which, in her case, appear to be experientially and not theoretically driven. In terms of its content, her artwork also gestures towards diversity. It represents diverse social groups, such as women, retirees, or people with disabilities, that have been previously excluded from political processes. By representing these groups and assembling the entirety of her work within one long tapestry (17.7x289.3 inches). Bazlova created a collective embroidered saga of the Belarusian uprising. Although the mode of production of this machine embroidery is different from the ritual abydzionnik towel, made by the village women and used in protection rituals, the collective ethos of Bazlova’s work is reminiscent of this folk form. Whether performed collectively or depicting a collective, these protest textiles carry the traces of a barely recognizable protection ritual from long ago.

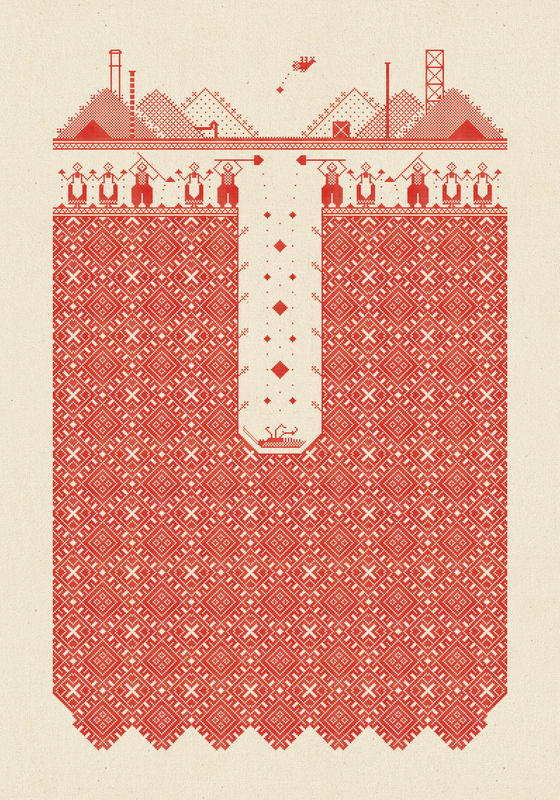

A piece from Rufina Bazlova’s series entitled The History of Belarusian Vyzhyvanka uses the traditional folk embroidery medium to depict the ongoing peaceful protests in Belarus, the artist’s home country. Based in the city of Salihorsk in the southern Minsk region, the Belaruskali Factory specializes in the production of potash. Its workers went on strike during the first days of the revolution, thus halting the mining. In the picture, they are burying a cockroach—a metaphor for Aliaksandr Lukashenka used by blogger Siarhei Tsikhanousky in his election campaign. Tsikhanousky also made a slipper (the folk weapon for killing cockroaches) a symbol of his campaign.

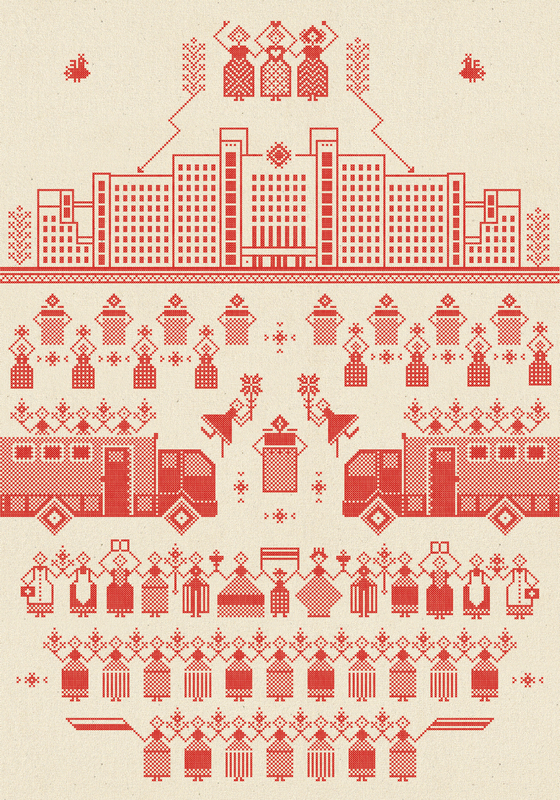

This second piece from Rufina Bazlova’s series entitled The History of Belarusian Vyzhyvanka depicts women-led protests in Belarus. On August 12, 2020, Belarusian women spontaneously took to the streets in large numbers calling for an end to state violence, forming solidarity chains and gathering across the country. Self-organizing in Telegram chats, they chose to dress in white, the traditional color of women’s suffrage. Hence, the Women in White movement was born. From August to October 2020, Belarusian women continued to participate in weekly Saturday marches, clashing with the police and breaking through police lines. All in all, there were four Saturday marches: the “Women’s Grand March for Freedom'' on August 29; “The Loudest March. Women March for Women on September 12; “The March of Sparkles” on September 19, which resulted in 400 detentions; and the “Démarche against Political Repressions” that took place on October 10. With the escalation of police violence against women, these massive marches subsided, while smaller decentralized forms of protest persisted.

This machine embroidery combines and unites the body of digital artwork made by Rufina Bazlova in her cycle The History of Belarusian Vyzhyvanka (2020–2021). Each tableau corresponds to an actual event during the Summer–Winter of 2020. This artwork was first exhibited as a part of the Every Day. Art. Solidarity. Resistance exhibition which took place in Kyiv’s Mystetskyi Arsenal from March 26–June 8, 2021. It was later exhibited as a part of Belarus––Screams of the Silenced exhibition at Haage’s Grey Space in the Middle from August 7–August 18, 2021.

Collective Embroidery Practices

Artists Biographies