Textiles in Belarusian Contemporary Art Before, During, and After the Protests

There has been a trend in contemporary art towards the use of textiles and folk art forms for at least the last five years. The Ukrainian art critic Alisa Lozhkina described the 2017 Venice Biennale as “dominated by textiles of all types and shapes –– threads, carpets, fabric installations, knitting, weaving, felting, patchwork” [Lozhkina 2017]. She further asks: “What is it? The realm of the victorious Yin energy? Femininity without feminism? Boudoir art, or a handicrafts club for bored housewives?” [Lozhkina 2017]. In the following half-decade, the trend continued to develop across the globe, while textile DIY practices gained even more relevance during the pandemic. A review of the New Museum Triennial 2021, for example, noted the “return of folklore and crafts, adding to these an even greater sense of retreat from anything too in-your-face or definite, maybe in reaction to an over-crowded, hyper-mediated culture” [Davis 2021].

In Belarus, a country isolated politically on the map of the world, the embroidery medium has been rediscovered only recently as “a powerful national icon and a political tool [Gapova 2017]. In contemporary art, it has been used before, but not widely. For example, one can mention Alexei Lunev’s project Shit-Clouds (2009-2010), elements of embroidery in Zhanna Gladko’s exhibition Inciting Force (2012), Olia Sosnovskaya’s project Of Our Women, a Two-channel video installation (2015), or Vasilisa Palianina and Anna Bundeleva’s artist embroideries [Razor and Bazlova 2021]. Evaluating the use of embroidery and protest textiles within the broader context of post-Soviet contemporary art in Belarus reveals that the particular appeal to nationhood is relatively new and emerged only within the past couple of years, as exemplified by the triptych titled Spadchyna [Heritage] (2019) by the Hrodna-based artist Daria Semchuk, who works under the alias Cemra (darkness in Belarusian). The impetus behind her work was to raise awareness of the loss of Belarus’ cultural heritage and to confront it [Chrysalis Mag 2021].

The Spadchina triptych features a traditional homespun dress and a homespun embroidered blanket with elements of graffiti by Hrodna-based artist Cemra. The artwork was first presented at the Autumn Salon: New Names program in the Art-Belarus gallery, April 9–13, 2019. The title, in Belarusian, means “heritage,” articulating a critical message directed at the disappearance of traditional culture in Belarus. The show spurred a public discussion about the artist's right to vandalize authentic artifacts, even though one such artifact shown in the exhibition was found in the dumpster.

Since the fraudulent presidential elections of August 9, 2020, Belarus as a country has become a battleground between the women-led democratic opposition forces and the violent authoritarian regime of Alexander Lukashenka. The Belarusian political system currently operates as a dual government, with Sviatlana Tsikahnouskaya, the independent candidate who likely won the election, heading the government in exile in Vilnius, Lithuania, and Lukashenka, who continues to usurp power in Belarus. According to the Belarus Freedom Forum [2022], from August 2020 to March 2022, 40,000 Belarusians were persecuted based on politically motivated charges and went through the country’s penitentiary system, while 1,077 political prisoners are still waiting for their release. Hundreds of thousands of Belarusians left the country but no reliable data exists to estimate the numbers of those who have emigrated. Belarusian society remains divided between the 39 percent who support Lukashenka and the 49 percent who actively oppose his regime [Astapenya 2021]. This struggle for democracy in Belarus is exacerbated by the loss of the country’s autonomy and the ongoing war in the region. Since winter 2021, Belarusian territory has effectively been occupied by the Russian military and is being used as a launchpad to attack Ukraine, with cooperation from the Belarusian military [Sullivan 2022].

From the beginning of the protests in August 2020, folklore has been a vehicle for articulating the protesters’ feelings, be it folk song performances or the use of traditional Belarusian bagpipes during the rallies. Some of these protest performances were consciously orchestrated by folklorists themselves. For example, the singing circle that met for one week in front of the Kupalausky theater was organized by folk musician and ethnographer Siarhei Douhushau [Douhushau 2021]. At the same time, other protest performances were more spontaneous and can be viewed, albeit with a certain amount of caution, as reflexes of folk rituals long gone. Consider this rally procession that took place on August 14, 2020, when students from the Department of Architecture at the Belarusian National Technical University carried a large stretch of white fabric across the Praspekt Nezalezhnasti [Gulin 2021]. Those familiar with traditional Belarusian textile rituals immediately recognize this as the ancient East Slavic protection ritual known as abydzionnik towel in Belarus. A group of women wove this type of ritual towel whenever the community felt threatened by epidemics, draughts or wars. Producing the towel had to take place from dusk to dawn or from dawn to dusk. Further, the ritual involved carrying this towel around the village and holding it across the road so that the villagers could go under it. Towels were finally displayed on crosses by the roadside or donated to the church [Labacheuskaia 2002; Gapova2006]. Abydzionnik rituals last occurred in Belarus during the Second World War [Labacheuskaia 2002]. In Spring 2020, the Student Ethnography Society reenacted it in connection with the pandemic [Svajksta 2020]. This exhibition uses the abydzionnik ritual rather loosely as a metaphor for protest cultural production in Belarus during 2020–2021, where the artist's labor was performed in groups and displayed online across the globe to raise awareness of the protesters’ plight.

Five days after the fraudulent presidential elections in Belarus, students from the Department of Architecture at the Belarusian National Technical University appeared at a protest march carrying a long stretch of white fabric across Praspekt Nezalezhnasti in Minsk. This photo shows the protesters marching past the infamous KGB building in the center of the city. The performance symbolizes the idea of solidarity chains, a strategy developed by the Belarusian protesters, where people lined up in the streets to voice their disapproval. Additionally, carrying this cloth across town is typologically similar to the ancient Slavic protection ritual of the abydzionnik towel, featuring a group of women carrying a long strip of homespun cloth around their village.

The abydzionnik towel is an ancient East Slavic protection ritual in which a group of women weaves a long strip of cloth thought to protect their community from epidemics, droughts, and wars. It had to be produced collectively between dusk and dawn, or from dawn to dusk. Women then carried their towels around the village and held them across the road, with villagers passing under them. These towels were later displayed on roadside crosses or donated to the church. These rituals last occurred during the Second World War, but in Spring 2020, the abydzionnik was revived by the Student Ethnography Society.

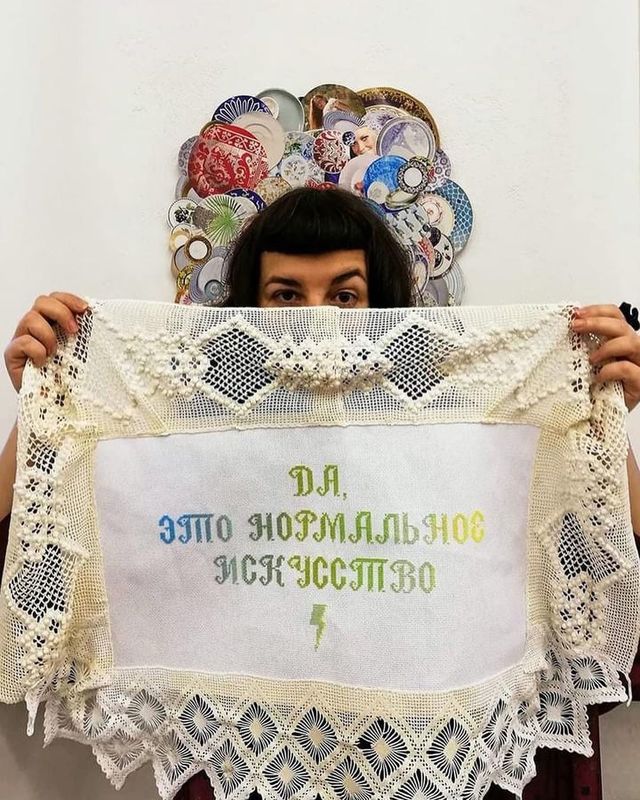

For a long time, textiles as a medium occupied the bottom rung of the art hierarchy and were included by art historians in a separate section of decorative and applied arts. In Western art, the rehabilitation of textiles as a medium occurred in the 1970s and was connected with the work of Second-wave feminists, who began to actively use traditional women's crafts in their works. In Belarusian contemporary art, due to the general weakness of the art scene and its institutions, textiles began to appear only in 2009-2010. Their emergence was associated with a growing interest in the West, the rise of a new generation of artists, the democratization of exhibition platforms and the proliferation of social networks. At the same time, the generally accepted Western term craftivism, a word that combines craft and activism, is popular in Belarus in rather narrow circles. Only a small percentage use this term, while the majority of artists working with political textiles do not associate themselves with this art movement. Despite the rapidly growing volume of works related to textile arts, this medium still remains outside the scope of attention of Belarusian curators who specialize in contemporary art. This group exhibition-archive is the first of its kind for Belarus.

In the events surrounding the 2020 election, Belarusians used many different types of textiles, including embroidery as a way to signify their Belarusianness at a time where visual communication was an important tool [LaVey 2021]. Collecting our material during a phase of mass repression in Belarus, we primarily thought of embroidery as material artifacts of the protest movement. These artifacts are situated at the intersection of manual and machine labor, of physical objects and their representation in the digital sphere. One of the peculiarities of dealing with the digital landscape during mass repression is the vulnerability of digital information. During the Fall and Winter of 2020 and 2021, Belarusian protesters often had to delete political posts from their social media profiles or their entire accounts. Instagram played an archival role during this time, while other initiatives could not keep up with the growing volume of cultural production and—except for one specially created platform, cultprotest.me—stopped their work during the protests. In our selection, we worked with the largest Belarusian protest web archive, Chrysalis Mag, which exists in parallel with Instagram, supplementing past editorial selections by viewing individual accounts and conducting interviews with artists. This exhibition included several works that the artists had in their archives but were afraid to display online. It also includes embroideries that were created in parallel with the process of working on the exhibition. Some of the artists wished to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Even though embroidery occupies a relatively marginal place in the entirety of the protest corpus, its dissemination online has a symbolic impact. This medium captured the public imagination in the first days following the elections, when artwork from the Instagram account of Prague-based Belarusian artist Rufina Bazlova made the rounds on social media and across a diverse spectrum of media outlets, including Radio Prague International, Die Welt, Gazeta Wyborcza, Belarusian-laguage Radio Liberty, Meduza, The Moscow Times, the Russian version of Republic, the Calvert Journal, and Global Voices, among others. Since August 2020, the idea of political embroidery has been actively implemented on several art platforms simultaneously. From August 20 to 26, Ў Gallery (the contemporary art exhibition space in Minsk that closed its doors in October 2020), launched the #TomorrowIsEveryDay project, in which more than ten artists offered their sketches to create a joint canvas-embroidery about the August events in the capital.

On 5 November 2020, another event titled Embroidery Practices, an online workshop on craftivism by Minsk artist Lesia Pcholka, took place. Pcholka’s larger project deals with researching family archives and embroidering women’s maiden names on their archival portraits. The collages of Germany-based Belarusian political artist Marina Naprushkina, which started as a part of #TomorrowIsEveryDay, stand somewhat apart. Published on Facebook, her work combines popular slogans in Belarusian with architectural blueprints made by her father, who was a Soviet architect; additionally, she does this all on the backdrop of school notebooks. Other protest embroidery that followed include works by Anna Bundeleva, Varvara Sudnik, Nasta Vasiuchenka, Daria Sazanovich, Vasilisa Palianina, Masha Maroz and Daria Golova. Galvanized by the protests, an entire community of Belarusian embroiderers has emerged among the county’s artists, documenting the events that took place, and working with such themes as feminism, memory and trauma. Whereas the dissemination of commercial ethnic patterns and consumer activism works to harness the idea of a nation, contemporary art activism tends to engage with additional referential frames, problematizing these narratives. Today, in an era of rapid loss of data and destruction of archival information in the region, protest textiles continue to serve a mnemonic function, organizing communities through their participation in protest rituals, documenting and working through political trauma through group participatory practices.

Craftivist Strategies of Belarusian Protest Embroideries