Shakespeare & The Restoration

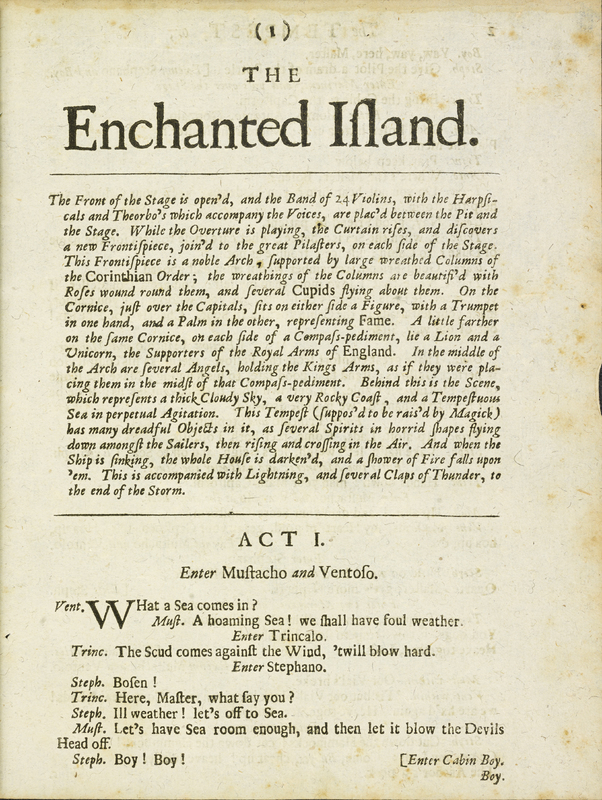

By the second half of the seventeenth century, Shakespeare was already considered a dated author. Thus, following the example of the Second, Third, and Fourth Folios, new editions of single plays modernized their spelling and grammar. On the stage, the plays were also drastically modified to satisfy the new tastes of the public filling the theaters, which had re-opened in the summer of 1660 after an eighteen-year official ban. For instance, the introduction of mechanical devices, changeable scenery, and musical entertainment between acts had a significant impact on the language and even the original plots.

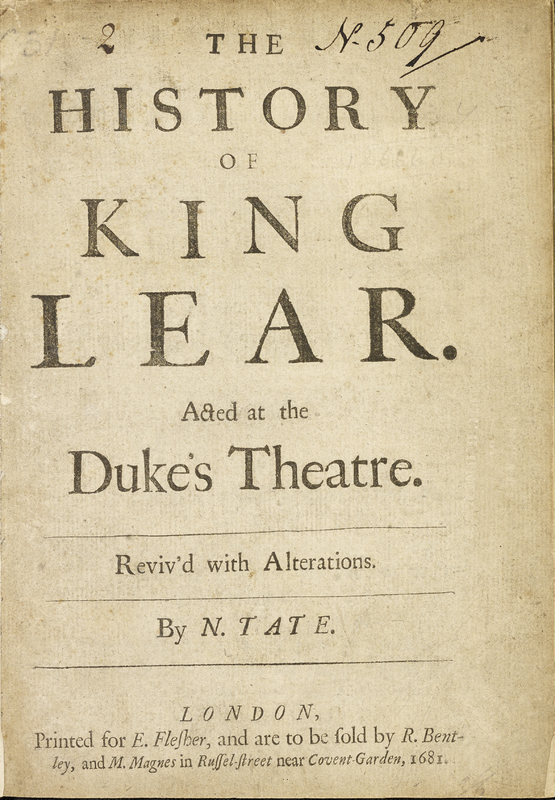

In 1660, William Davenant asked the Lord Chamberlain for the right to perform nine plays by Shakespeare, including "a proposition of reforminge some of the most ancient Playes that were played at Blackfriars and of makeinge them, fitt." John Dryden's attitude as an editor of Shakespeare was clearly expressed in his preface to Troilus and Cressida. He argued that he has written the play because "the whole stile is so pester's with Figurative expressions that it is as affected as it is obscured." In his adaptation of King Lear, Nahum Tate inserted numerous changes in the plot itself: he added the Edgar-Cordelia love story, expanded the female roles -since women were then allowed to act -and eliminated the role of the fool. More notoriously, he even changed the ending: King Lear is left alive at the end of the play.

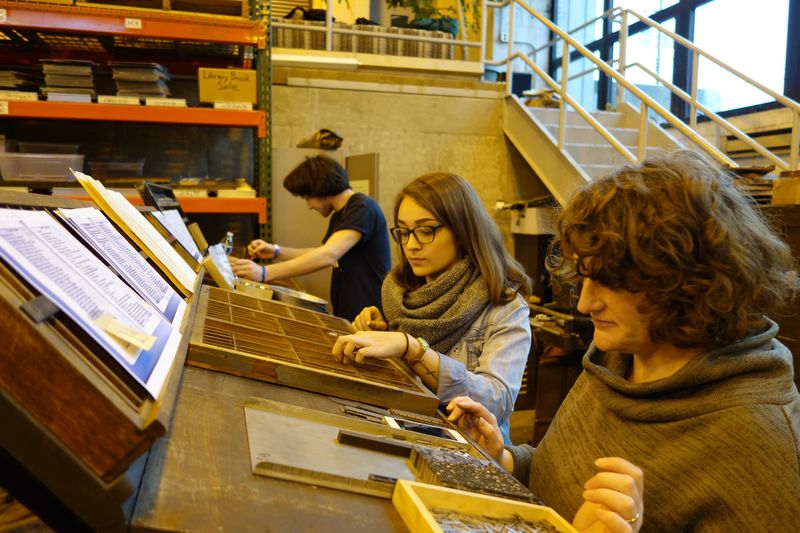

Hamlet and the Wolverine Press

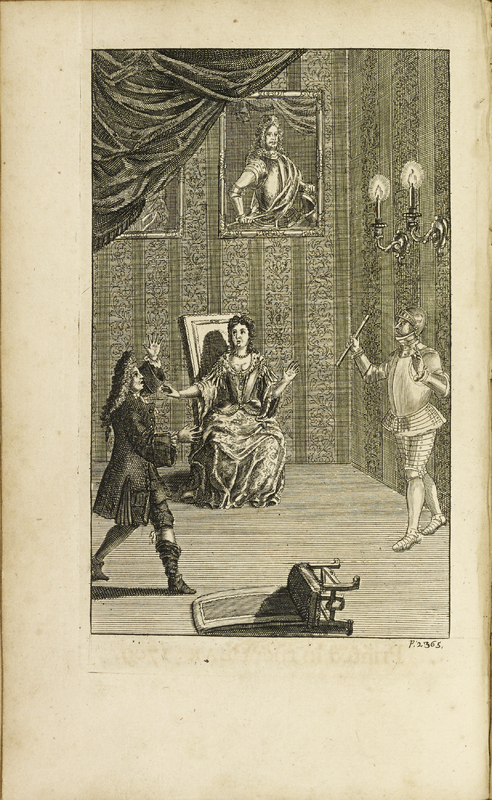

Illustrating Shakespeare