Peter Pan

J.M. Barrie's Peter Pan & Wendy (1951). May Byron (author). Mabel Lucie Attwell (illustrator)

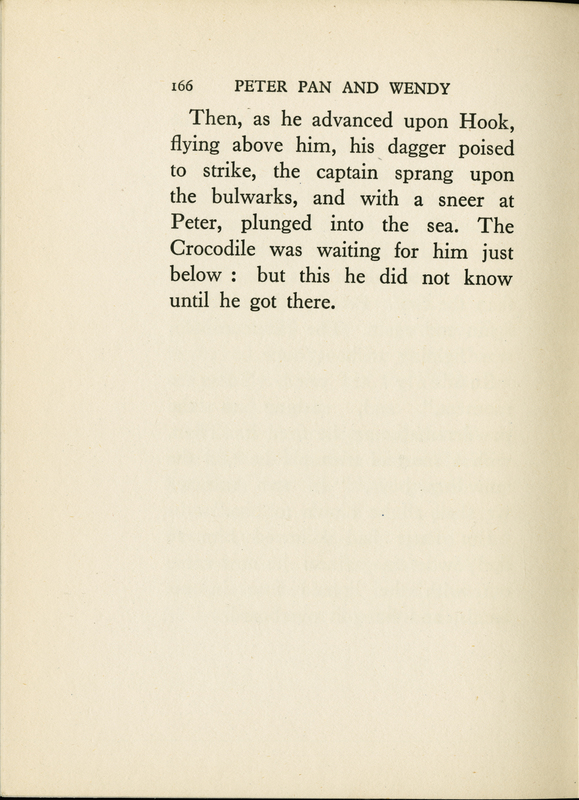

This 1938 version of Peter Pan, adapted by May Byron, retells J. M. Barrie’s original multidimensional story as a black-and-white tale of good and evil. Here on page 166 we see the text describing Peter Pan and Captain Hook’s final battle. In this version, Peter severely wounds Hook but maintains what the text calls “good form” by refusing to fight when Hook is unarmed. Hook then retaliates with bad form and is promptly killed by the crocodile.

Maria Tatar, a scholar of children’s literature, argues that Barrie’s Peter and Wendy paints both Hook and Peter as childlike, presenting their violence as a game. In Byron’s adaptation, Hook is disconnected from this childishness, and his villainy is amplified in order to make the story more exciting. Hook’s unfairness in this version bends readers in fearless Peter’s favor, whereas in Barrie’s version, careless Peter is the one engaging in bad form. Barrie’s Hook identifies this bad form, giving him—the antagonist—contentment in death. Byron’s child-centric adaptation, however, strives to please children with a simple revenge plot rather than with complex characters.

Yet some scholars insist that Peter isn’t fearless and is instead driven by his fear of time. Time, represented by a ticking crocodile, claims Hook in the end. In Barrie’s version, Peter cries that night, detracting from his heroic perfection. But Byron’s adaptation simplifies Peter’s conflict; against villainous Hook, such a fearless hero would be a good model for children, reassuring them that courage always yields happy endings.

Sydney Bentley and Gabrielle Roth

Walt Disney's Peter Pan: From the Motion Picture "Peter Pan" (1952). John Hench (illustrator). Al Dempster (illustrator)

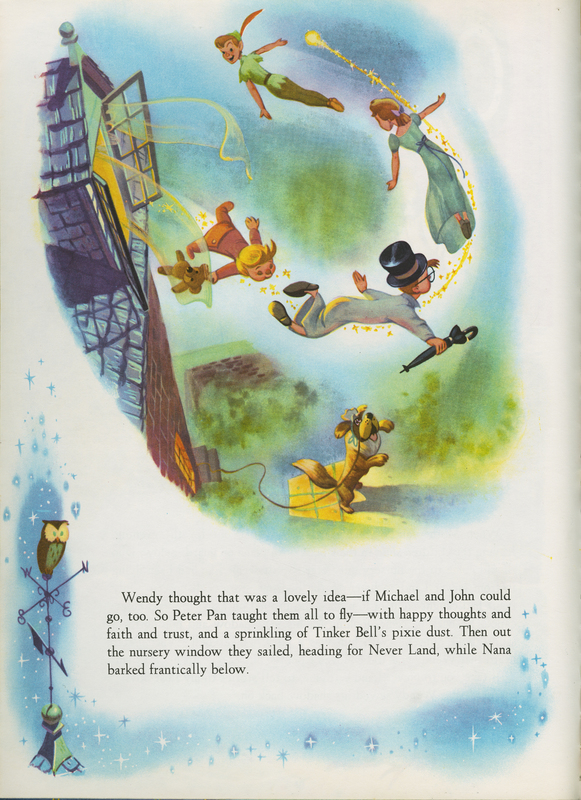

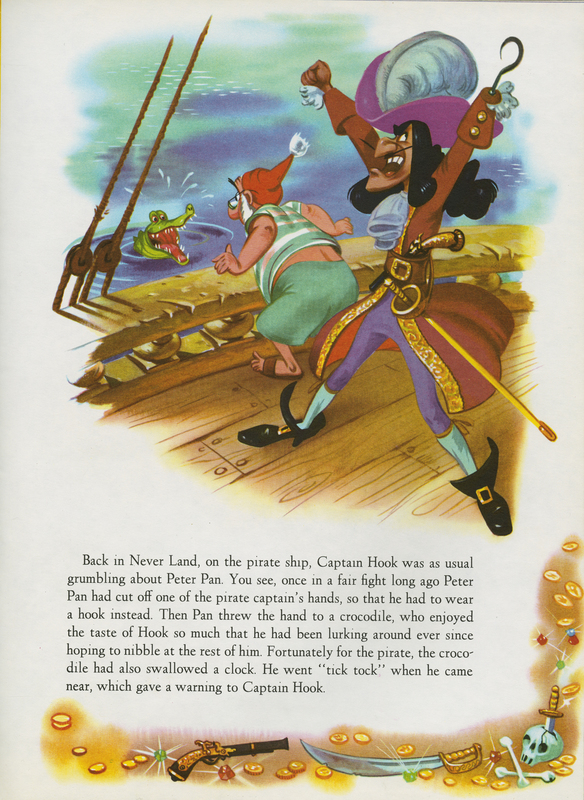

The Golden Book edition of Peter Pan, published in 1967, is adapted from the Disney film. In the book, Wendy, John, and Michael are taken to the wonderful world of Neverland, where they experience adventure and trouble, learn the importance of family, and discover that every child must one day grow up. Pictured here is the first moment in which the Darling children freeze their childhood selves in Neverland and search for independence away from their parents. Captain Hook, the only adult character in Neverland in this edition, causes the children to realize that they eventually will grow up, but for now they should appreciate the life they have in London with their parents.

J.M. Barrie, the original author of Peter Pan, was himself known as a boy who would never grow up, and in the novel he uses his own experiences to depict what critic Sarah Gilead calls “the adult’s romantic view of childhood as the liberated imagination itself.” Barrie’s opinions about the relationship between children and their parents and his ideas about what “growing up” means are explored in Peter Pan. This edition of Peter Pan mirrors the Disney film in both content and artwork. It was produced to bring the magic of Barrie’s story and the art that Disney created for the screen into the hands of adults and children everywhere.

Alexis Michaels and Casey Werman

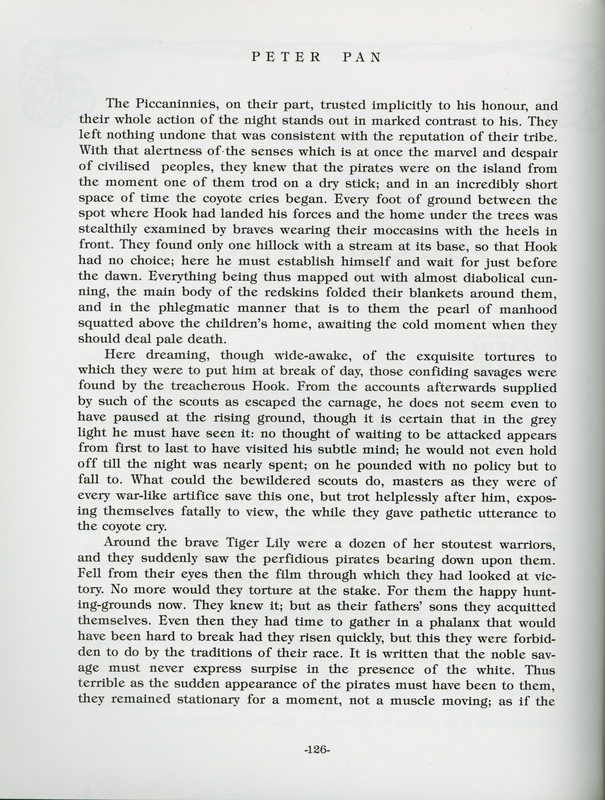

Peter Pan (1987). J.M. Barrie (author). Greg Hildebrandt (illustrator)

In the 1987 edition of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, the indigenous tribe is victim to Barrie’s use of racial stereotypes; their depictions accentuate the wildness and savagery of Neverland. In this edition, and in Barrie’s original text, the tribe and their leader, Tiger Lily, are described with language that associates them with excessiveness and violence. They prowl Neverland searching for pirates while “[carrying] tomahawks and knives… [while] their naked bodies gleam with paint and oil.” Barrie goes on, stating that “strung around them are scalps, of boys as well as of pirates, for these are the Piccaninny tribe.” However, the illustrator of this edition, Greg Hildebrandt, makes some effort to present a more nuanced, though still problematic, portrayal of the Native characters.

In his illustration “Hook’s Pirates Fight Tiger Lily’s Redskins,” Hildebrandt chooses to clothe the tribe in leather, while leaving their faces bare of oil and paint; there is also a notable absence of scalps as decorations. Their actions are more controlled within Hildebrandt’s illustration than in the text, as pirates are not brutalized but are instead left unconscious in the grass.

While failing to escape from an illustrative tradition of racist stereotypes in the depiction of Native peoples, Hildebrandt’s illustrations arguably attempt to avoid the worst excesses of the text, and in the case of Tiger Lily, allow readers to read her expression and see her as an individual and more three-dimensional character.

Neena Pio and Holli Schlukebir

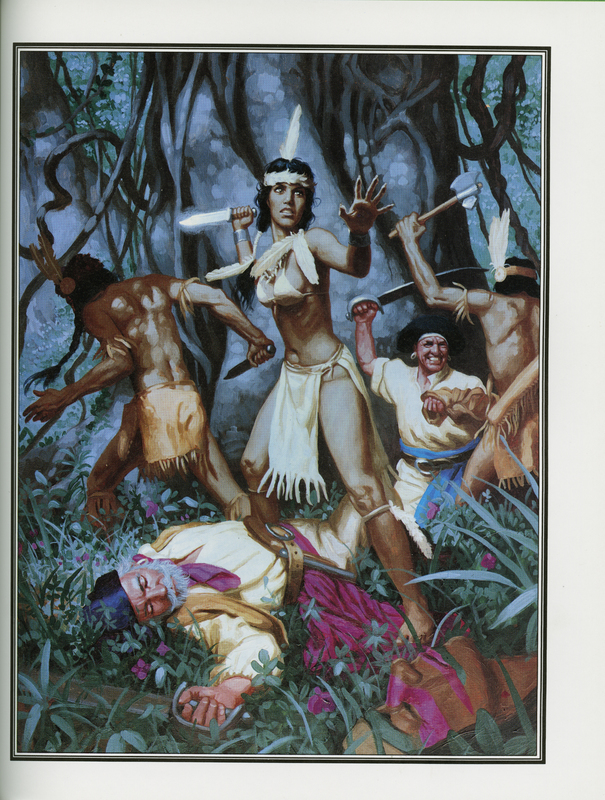

Peter Pan: A Pop-up Adaptation of J.M. Barrie's Original Tale (2008). J.M. Barrie (author). Robert Sabuda (paper engineer)

Attempting to rekindle book buying for children during the American Great Depression, Blue Ribbon Publishing created moveable book versions of traditional fairy tales with pop-out images, coining the term “pop-ups.” While the popularity of children’s pop-up books continues to grow, artists like Robert Sabuda have developed innovative paper engineering techniques. Sabuda’s 2008 adaptation of J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy brings the classic childhood fairy tale to life with his clever fold-out pages and pop-up scenes. As Tinkerbell, Wendy, Michael, John, and Peter Pan fly through the pages, Sabuda’s vibrant illustrations transport readers into a three-dimensional Neverland. The fragility of the intricate artwork and the small, dense font suggest that Sabuda intended that adults read this book to young children, helping them to handle the delicate pop-ups.

This pirate ship scene is the last of the six scenes Sabuda chose to illustrate. The climax of the story takes place on the ship, where the children’s lives are endangered by Captain Hook. Dominating two full pages of this short book, the ship is massive in comparison to the miniature faceless characters on board. In his rendering of this scene, Sabuda omits the violence and emotion present in Barrie’s original text. Unlike Barrie’s text, Sabuda’s illustrations do not show the children in any immediate danger, and his text leaves out details of Hook’s death. The simplification of this scene reinforces the idea that the purpose of this adaptation is to present Barrie’s story to a young audience in a lighthearted and playful way.

Ally Lazarus and Allie Wilk

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Aladdin