Cinderella

Cinderella (1981). Hilary Knight (author and illustrator)

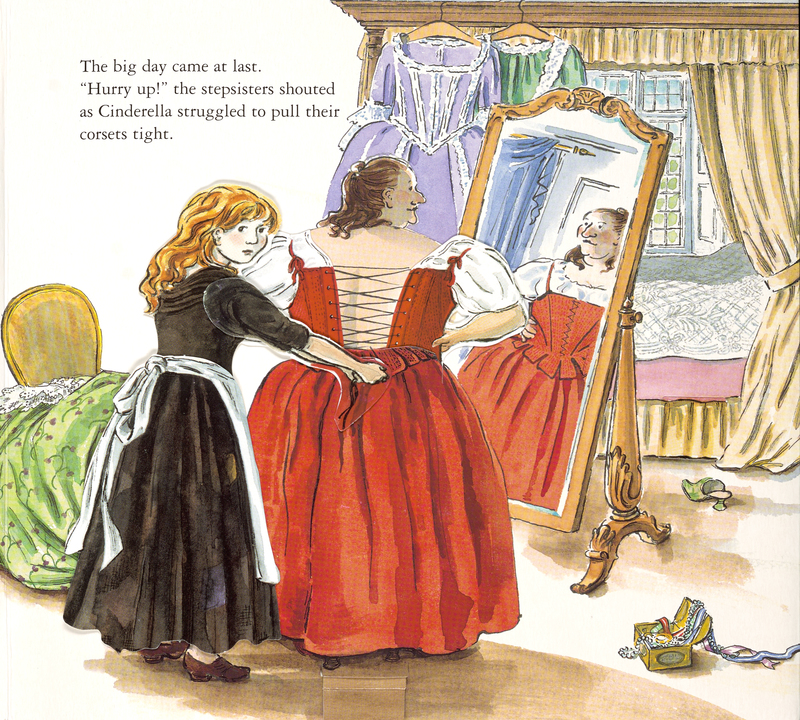

The original tale of Cinderella, as composed by Charles Perrault, features a protagonist who is obedient, forgiving, passive, and beautiful, exemplifying the ideal woman within a patriarchal society. Perrault’s narrative reinforces the strict gender roles of France in the 17th century, still prevalent in the narrative of Hilary Knight’s 1978 edition, shown here in its 1981 paperback edition. However, during the late 1970s, when this edition was first published, the United States was in the midst of a social movement that rebelled against societal pressures to redomesticate women post-WWII. This feminist movement became integrated into many aspects of and artifacts in American society, including the illustrations in Knight’s edition, which challenge traditional notions of domesticity. Contradictions between the narrative and the illustrations are evident in Knight’s version, which encourages feminist values despite the patriarchy-influenced text. Although Knight’s narrative glorifies the domestic value of marriage, the illustration above depicts domesticity as a limitation to female independence.

The image shows Cinderella entrapped by both the illustration and binding of the book itself. She is located in the house on the left page, while the outside world is portrayed on the right page. The house is filled with objects that take up most of the illustration, while the outside world is open. Also, the mice outside are in cages, while those inside are instead caged by the walls of the house, just like Cinderella. Thus there is a clear binary established between the domestic world and the outside world. The illustration undermines the value of domesticity by inhibiting Cinderella’s ability to leave the domestic space (without the help of her fairy godmother, of course).

Allison Shaune and Alexus Little

The Egyptian Cinderella (1989). Shirley Climo (author). Ruth Heller (illustrator)

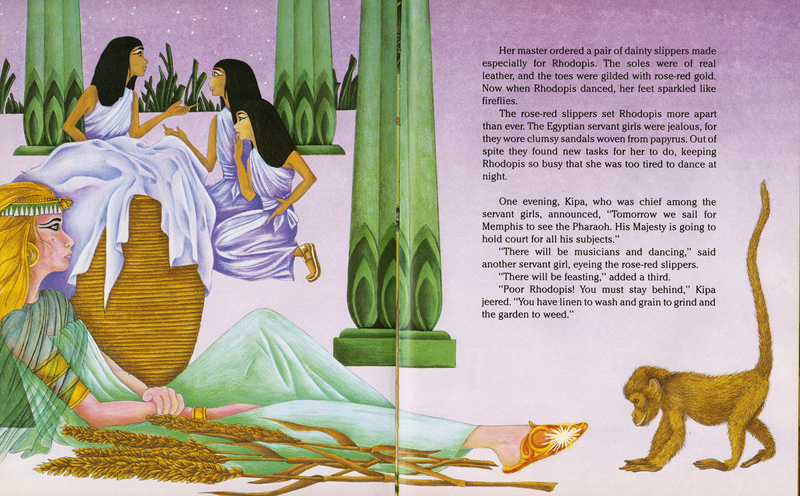

Shirley Climo re-introduced the Greco-Egyptian story of Rhodopis with her publication of The Egyptian Cinderella in 1989. The story of Rhodopis was first recorded in Geographica by the Greek geographer Strabo in the 1st century BC, making it the earliest-known recorded Cinderella story. Climo’s tale is modeled after the historical tale of the Greek slave girl Rhodopis, who, after being captured by pirates, was sold into the Egyptian slave trade. Though the tale is widely accepted by historians as a unique cultural twist on a classic fairytale, many critics feel that the servant girls’ racist attitudes towards Rhodopis for being Greek rather than Egyptian make the tale unsuitable for contemporary child readers.

The name Rhodopis means “rosy-cheeked” in Greek. Along with her Grecian name and origins, Rhodopis’s fair skin and sunburnt cheeks were uncommon traits in the Egyptian world and cause her to be a social outcast among the other servant girls in the story. The illustration exemplifies this, presenting a stark contrast between her rosy skin color and the darker skin tone of the other girls. Each page seems to emphasize how different the protagonist is from her surroundings. In the end, Climo’s tale follows the classic romantic Cinderella plot line as the Egyptian pharaoh, Amasis, falls in love with Rhodopis because of her unique physical attributes. Climo uses this ending to shift attention away from the racism in the story and to emphasize the beauty of human differences in society.

Nicole Haggerty and Alyssa Moy

Walt Disney's Cinderella (1995). Suzanne Ferguson (designer). Franc Mateu (illustrator). José R. Seminario (paper engineer)

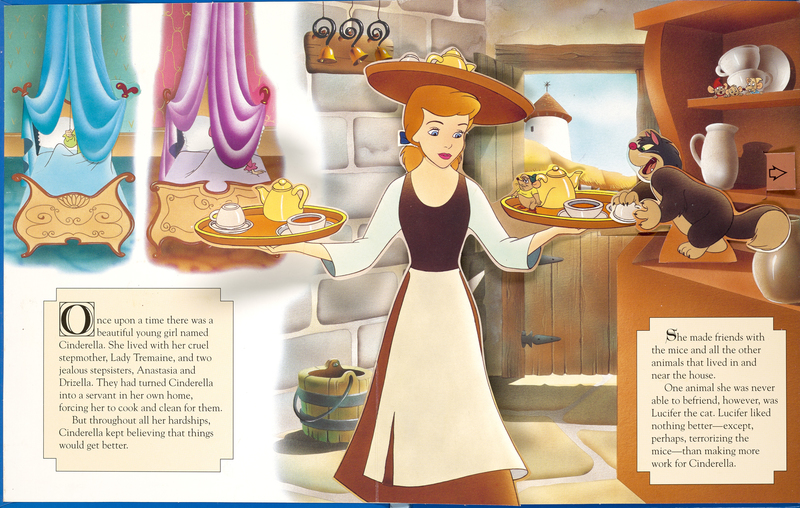

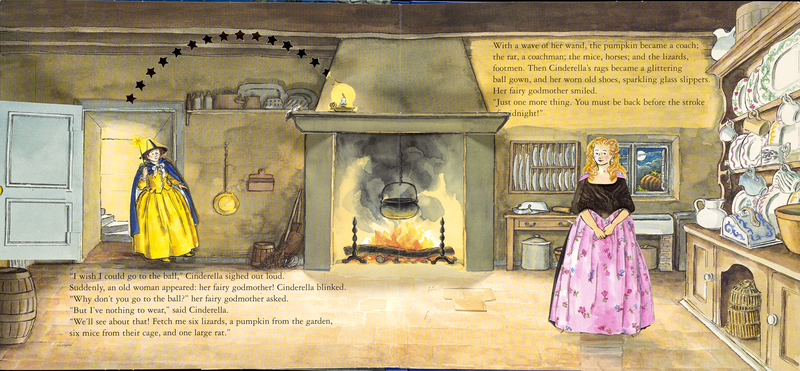

Cinderella is a fairy tale that is hundreds of years old, but Walt Disney’s 1950 animated Cinderella is the version that comes to mind when many think of the tale today. It is not widely known that the conflict between Cinderella’s animal allies and the stepmother’s pet, Lucifer, was added to the narrative by Walt Disney. Disney’s addition adds intensity to the tale by associating Cinderella with animals. By developing this drama between animals, deeper meaning is created within Cinderella’s life. Lucifer, the stepmother’s cat, is viewed as a villain as his name means Satan, or the devil. The mice, by contrast, are introduced as fun-loving characters that are willing to help Cinderella. This aspect of the plot mirrors the main story of Cinderella as Lucifer is depicted as representative of Cinderella’s stepmother and the mice of Cinderella.

By placing animals on the first page, the author sets the stage for the animals to have a significant role within the plot. In the picture, the mice stand with Cinderella, while Lucifer is placed opposite them, trying to steal their food. Furthermore, when the fairy godmother transforms Cinderella for the ball, she also transforms everything that is a part of Cinderella’s life, notably turning the mice into humans. Although they eventually return to mouse form, for the short time that they are humans they mirror Cinderella’s qualities of light and love. The ending of the story highlights the connection of these animals to their human counterparts. Of course, in the end, both mice and heroine live happily ever after.

Halle Blum and Samantha Gilberg

Adelita (2002). Tomie DePaola (author and illustrator)

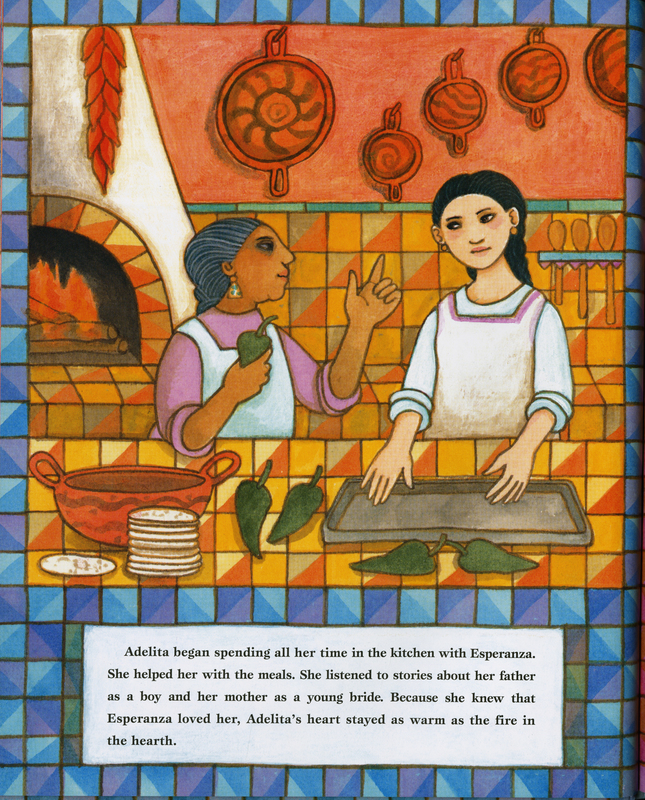

Tomie DePaola’s Adelita offers a refreshing twist on Disney’s Cinderella story through the incorporation of Mexican culture, putting a minority culture in the forefront of an American children’s book. Linda B. Alexander notes in her article “Multicultural Cinderella: This is Fun Work!” that by 2020, “nearly half of U.S. students will be people of color, which increases the need for children to view themselves as members of a multicultural global community.” DePaola’s Adelita encourages child readers to understand themselves in this way.

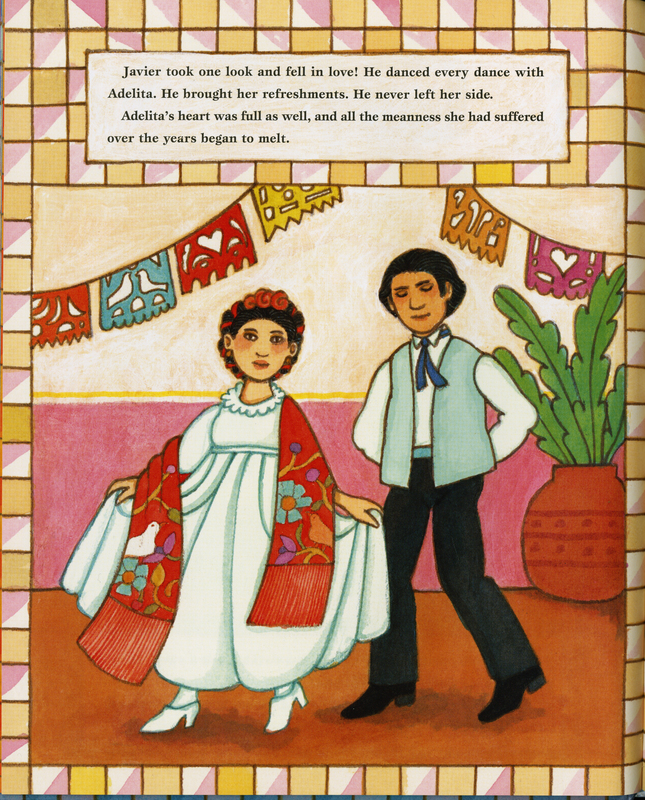

DePaola sets the story in a Mexican town sometime in the past century. The common Spanish phrases integrated throughout the text create a bilingual reading experience accessible to even novice Spanish speakers. The illustrations depict the bright colors of Mexico, and DePaola incorporates Mexican cultural items into his illustrations such as crosses, crafts, pottery, kitchenware, and architectural design. Although the story resembles Disney’s Cinderella, there are crucial differences. Instead of the Prince finding Cinderella with the glass slipper, Adelita uses her mother’s red shawl, designed with birds and flowers, to help the prince figure, Javier, find her. The characters are also aware of the Cinderella story and even mock it—evident when the stepmother Doña Micaela expresses her joy that there’s no glass slipper for Javier to use to find his Cinderella. Finally, at the end, Adelita asks Donã Micaela for permission to marry Javier despite being treated poorly by her stepmother earlier in the story, reinforcing the prioritization of the tradition of respect towards elders in Mexican culture. This respect is reciprocated by Doña Micaela to Adelita when she permits Adelita to marry.

Sergio Villaseñor and Kathleen Ortiz

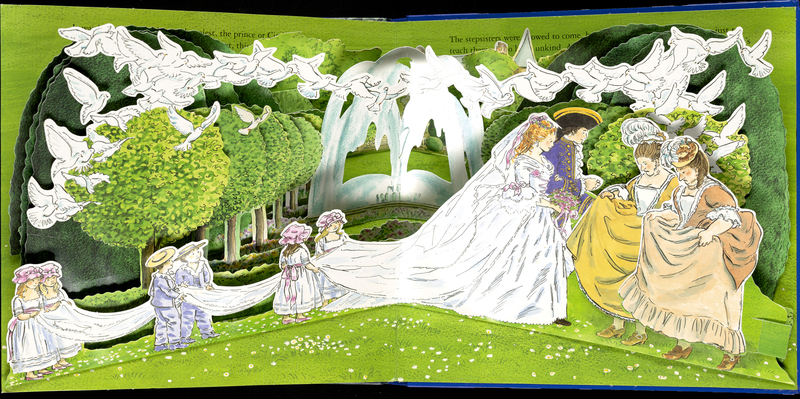

Cinderella: A Pop-up Book (2006). Phillida Gili (author). Nick Denchfield (paper engineer).

Written in 2006 by Phillida Gili, this edition of Cinderella features pop-up images and movable tabs that allow the reader to interact with the text in a physical manner. The final page of the book is intricately and elegantly designed, depicting the scene in which Cinderella marries the prince. The pop-up wedding image and the tab that enables the reader to make the stepsisters curtsy to Cinderella allow children to understand the stepsisters’ newfound respect for Cinderella better than they would with text alone. The visual movement generated by the tabs makes the images more entertaining to the reader than a static illustration.

This edition of Cinderella differs from many other versions in that it features a lack of parental control over both Cinderella and her stepsisters. Although in most renderings of the tale an evil stepmother plays the role of Cinderella’s adversary, in Gili’s story there is no mention of either Cinderella’s stepmother or her biological parents. The only parental figure included in the story is the king, who plays the small role of inviting the family to the ball. The lack of parenting and supervision seems to encourage the two stepsisters to mistreat Cinderella more than in alternate versions. In the Disney film, by contrast, the stepmother is an abusive figure to whom the stepsisters complain about Cinderella, thus the stepsisters are presented as less mature and less powerful

Theoren Moore and John Oben

Aladdin

Little Red Riding Hood