The American Revolution

The concurrence of the Enlightenment and the American Revolution were no coincidence. Throughout the Enlightenment era, the spread of new ideas about government, reason and natural rights spread from Europe throughout the Western world. The influence on colonial American thinkers and politicians was evident in many of the works of eighteenth century writers and philosophers like Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin. Individuals began analyzing the British framework of government through a radical lens that gave rise to new waves of political thought. The Enlightenment influenced the American patriot separatists’ position in their debate with those loyal to the British Crown.

The idea for an American Revolution gained favor partially due to the rise of print culture which made wide distribution of new ideas and information possible. This expanded the public sphere of political discourse to include not only members of the colonial political elite, but also lower class people with less education. Further, migrants from Europe as well as American-born colonists were drawn into these conversations. The ideas circulating throughout the colonies suggested possibilities for new configurations of government and society that some colonists preferred to those supported by the British Crown. However, despite the expansion of the public sphere, discussions about politics and society were still dominated by the white male perspective in the colonies. This limited perspective is reflected in the surviving print documentation of this period.

Riley Branigan and Julia Nevison

Common Sense was originally published in Philadelphia in 1776. This new edition from the same year is a small book with no images and unevenly cut pages. The section of Common Sense displayed here outlines Paine’s critique of monarchy and the inevitability of the failure of the British government. The impact of this piece comes more from Paine’s writing style and intended audience than the uniqueness of his ideas. The direct and simple prose is representative of Paine’s entire pamphlet. This accessible writing style widened the public sphere to include colonists of lower education and social status. Although Paine emigrated from England to Pennsylvania just a few months before he published Common Sense, his devotion to the American Revolutionary cause gained the support of the American colonists. Paine claims that the British system is doomed to fail because of the mutually antagonistic interests of the two houses of Parliament and the King. Paine attacks the King directly, arguing that he is often concerned with his own interests and constantly needs to have his power checked by other branches of government. Further, he states that kings are too sheltered from the public world that they are supposed to represent. These ideas were not original to Paine, but the effectiveness of his writing allowed a greater number of people to be mobilized in the debate over American independence.

Riley Branigan and Julia Nevison

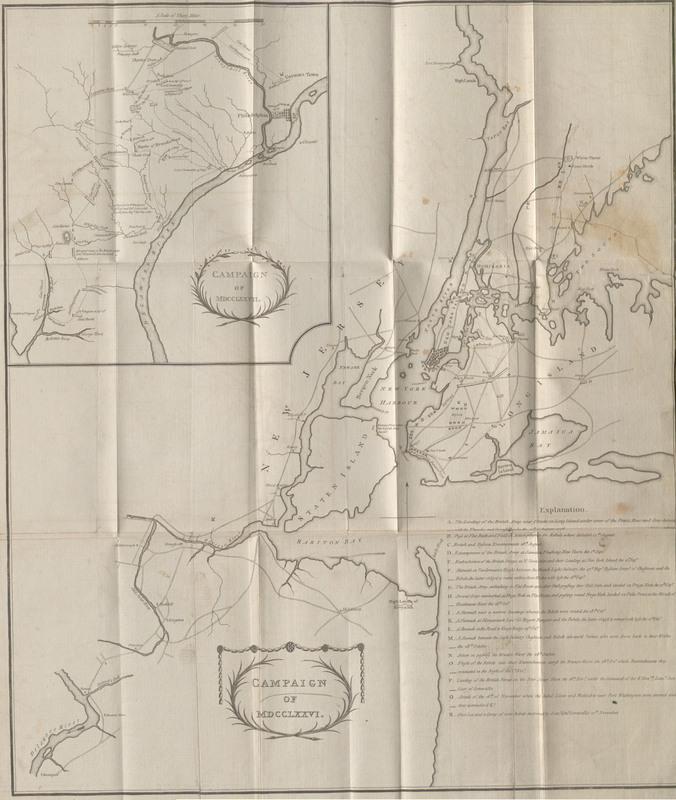

While we typically connote the phrase "Civil War" with the American war that took place from 1861-1865, the title of The History of the Civil War in America refers to the American Revolution. The map on display, placed between the table of contents and the first chapter, folds open several times the size of the book pages. It portrays the tremendous casualties and defeats suffered by Washington’s army in the New York campaign of 1776, the lowest point in George Washington’s military career. The map shows the Long/Staten island areas, with New Jersey on the left side, and the Delaware river extending into the lower left. A map of the 1777 campaign is displayed in the upper left and a legend is housed in the lower right. When this book was written, New York was still under British control and remained so until the war’s end in 1783. The "explanation" in the bottom right details points A-R on the map. These points include crossed swords denoting battles, crosses denoting towns, and rectangles denoting forts. It is presumed the intended audience was other officers of the rebel army; its purpose was to keep records of British advances. Interestingly, the map used darker ink to represent water and lighter ink to represent land, the opposite of the color scheme used in most modern day maps.

Cadence Litt and Madeline Treber

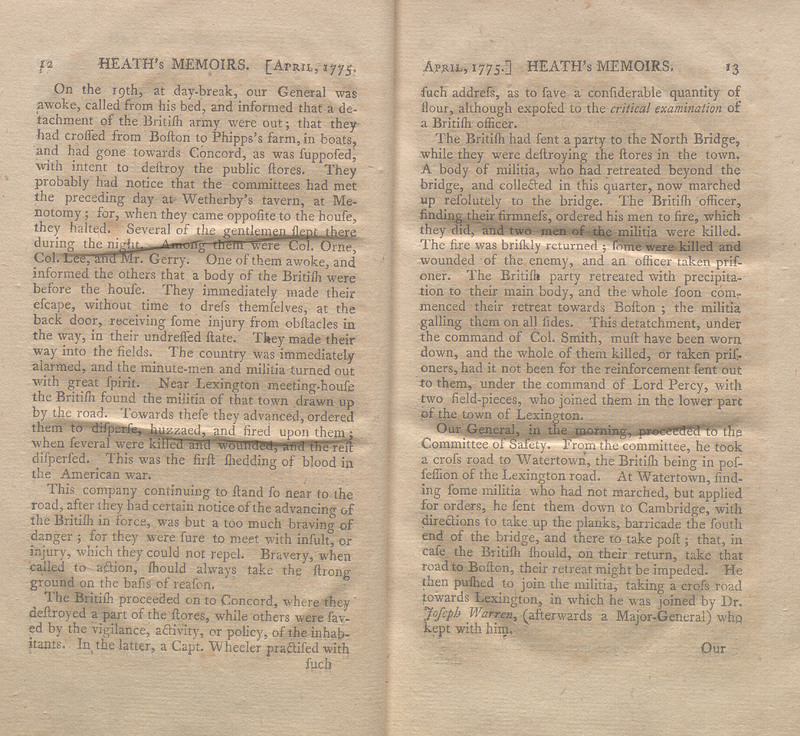

Although bound in a plain leather binding without designs or illustration, this first-person account by Major-General William Heath of the Battles of Lexington and Concord is a significant and unique document. The pages on display reference what is widely known as the "shot heard round the world," as well as the first shedding of American blood in the Revolutionary War. Many nonfiction accounts of war contain dramatic language and sensational description, but this is not the case in Heath’s memoir of the events. His writing is very pragmatic and explanatory. This document strives to give an accurate account of the warfare and strategies employed by both sides, allowing a reader to understand the minutiae of the tactics involved in these initial battles. There is a specific date associated with each entry, making Heath’s narrative easy to follow. The book was published less than 25 years after the battles, and would have been a good way for people at the time to study the events surrounding the formation of the United States, at a time when many of the people who actually lived through those events were passing away.

Stacey Berliner and Jonah Griff

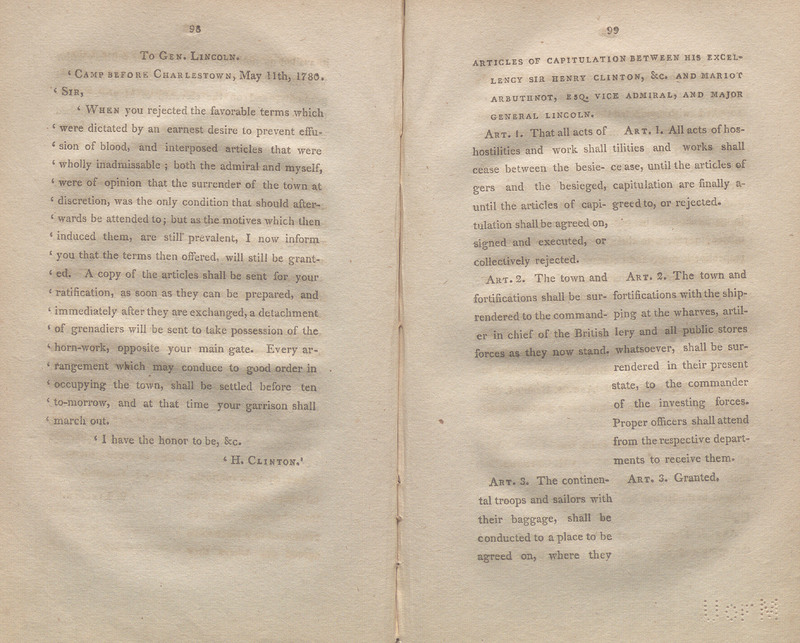

In early 1780, the British launched a coordinated land and sea assault on Charleston. The Americans were well aware the British land force was pushing well into the South Carolina low country, but chose to make a stand at Charleston; however, the Americans were caught off guard by the British Navy, who seized the harbor and destroyed America's escape route and supply chain. Completely surrounded on all sides by the most powerful military in the world, the rag-tag American army under the command of Generals Moultrie and Lincoln surrendered to British General Henry Clinton on May 12, 1780. The terms of surrender were hotly debated between the staff officers of the Americans and British; after several volleys of letters, General Clinton writes General Lincoln to "inform [him] that the terms then offered, will be granted." On display here is a page from William Moultrie’s memoir, showing a copy of this particular letter. Each new line begins with an apostrophe, noting that it was quoted from someone other than General Moultrie.

The outcome of this siege highlights the advantage that superior numbers and a skilled navy gave to the British, in this case ensuring their victory. General Moultrie’s account of the siege uses a copious amount of military jargon. This specialized vocabulary suggests that the book may have been compiled with an audience in mind who was familiar with military terminology, perhaps for veterans and other survivors of the war.

Zach Breininger and Adrien Kelly

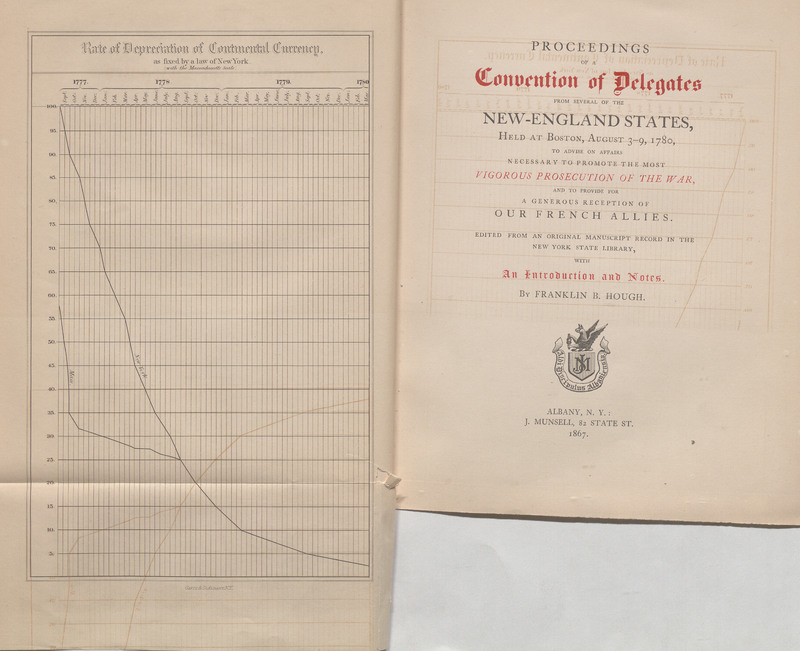

The binding of the book is composed of irregular sheets, originally bound uncut. Therefore, the roughly-cut edges reveal the journey of the reader. The pages have wide margins and large font, suggesting an elite audience. The book is a collection of letters exchanged by the Founding Fathers and a report of the Bostonian Convention in 1780, at a time when the American Revolutionary War was actively being fought by the original 13 colonies striving to gain independence from Britain. This Convention gathered in an effort to resolve the exhaustion of resources resulting from the war. The graph on the inside cover visually depicts the exponential decline in the currency of Massachusetts and New York from 1777 to 1780. Chairman of the committee of Congress John Matthews includes his call to action to Congress, saying "[it is] our duty to our country [and he refused to] submit to the loss of the country" (xxv).

This edition, with an introduction and notes by Franklin B. Hough, was issued in 1867. It seems likely that reprinting these documents in a lavish edition at that time made sense for Northerners seeking to bolster their claims to a Federalist and Unionist heritage, as the text gives historical evidences that the Founding Fathers were in favor of a strong Union. Perhaps the fact that the editor and publisher chose chose a text from just before the decisive French intervention in the Revolution might also have significance. There could have been a desire to elide France’s role in the Revolution because of its ambiguous position during the Civil War. The ideas presented in these letters and Convention documents later led to the Federal Convention of 1787 that would bury the Confederation article and adopt the federalist Constitution of the United States.

Benoit Lichtenauer and Jasmine Rogan

The text comes in two small, leather-bound volumes, divided into several hundred poems. The poems in this text are written by various authors and were collected by Philip Freneau, a poet and veteran of the revolutionary war, famous for his satirical prose and founding of the National Gazette, a famous political newspaper of the late 1700s. The poem on display, "On the British King’s Speech Recommending Peace with the American States," is written by Freneau in his typical satirical style. Unlike much of the poetry in these two volumes, this piece is directed not at an American audience but at other British colonists, citizens, and especially the people of Ireland and Scotland.

Freneau declares King George a tyrant who has rendered the British Parliament and Prime Minister (Old Bute and North) powerless to stop his ambition. He prays that King George will never see peace and curses anyone that would trade with Britain. Finally he calls on Ireland and Scotland to seize back their homelands, throw off the British yolk, and put an end to the British empire once and for all. Freneau had lost friends in the war, and had been captured and held prisoner by the British, and through this poem he conveys his pain and hatred to the world in the hopes of inspiring more revolutions.

Brittney Jang and David Whalen

Description and Travel