Abolition and the Civil War

In the 1860s, the United States was undergoing a period of social and economic transition. With the start of the Civil War in 1861, Northerners and Southerners alike had to grapple with the contradictory ideas of slavery and freedom. This era determined what kind of country America would strive to be—one of oppression or one of freedom for all people. Tensions began to boil over with the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, culminating in South Carolina and other states seceding from the Union to form the Confederate States of America. The national consensus in the Northern Union states was in favor of abolition, while the Southern Confederate states sought to maintain slavery as an institution.

Within these two broad geographical areas, many individuals had their own opinions on the matter. African-Americans in the South obviously opposed being enslaved, and many in the North resisted recognizing the evils of slavery, in part because it powered so much of the American economy. In this historical moment, when the destination of America hung in the balance, both common people and famous authors took pen to paper to write about their views on slavery, abolition, and the Civil War at large. The topic permeated all facets of life: diaries, poetry, historical accounts, and best-sellers were hard pressed to ignore the attitudes and goings on of the country at this time.

Brooke Christians and Brendon Haithcock

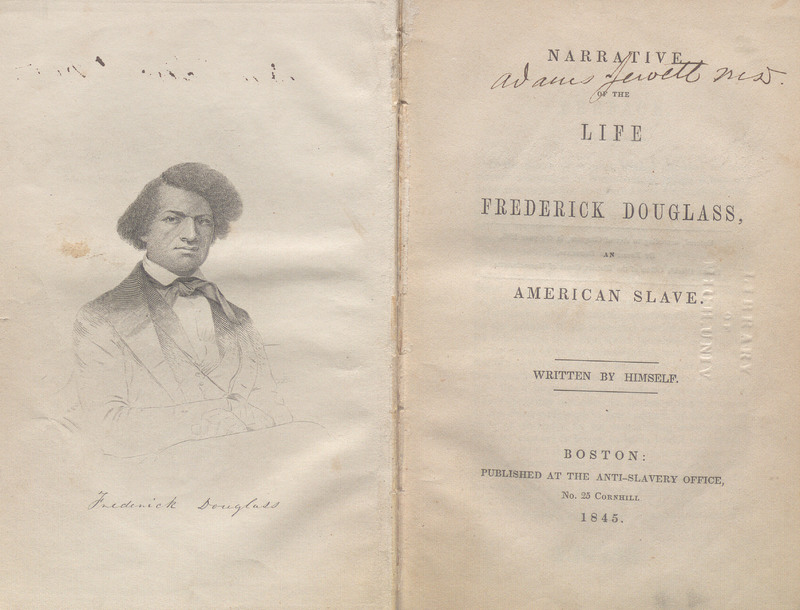

Frederick Douglass’ portrait is on the frontispiece of his autobiography. The portrait is a black and white sketch of Douglass’s face and upper body. He is pictured in aristocratic clothing, displaying the juxtaposition between his high societal status, and his race. His face is drawn with more detail, while his chest is sketched lightly.

Frederick Douglass was a slave in Maryland, who eventually escaped slavery and moved to New York in 1838. After moving to Massachusetts Boston, Douglass became active in the Abolitionist movement. Having taught himself how to read and write while enslaved, Douglass was able to tell his own story in his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, published in 1845, Within the biography, Douglass describes the ordeals he experienced as a slave and his subsequent journey to freedom. As a speaker and author, Douglass acted as a strong, leading voice for the abolition movement.. His recollection of his own experiences proved to be a powerful tool of reasoning and helped him become a leading social reformer. Many were influenced by his autobiography to sympathize with the abolitionist movement. His autobiography specifically acted as a rallying point for people of color, as they started to demand rights. Frederick’s autobiography was published in Boston, by the Anti-Slavery Office, a multiracial organization that strongly advocated and campaigned for abolition. Boston was the hub of the abolition movement, which began through the collaboration of free blacks and fugitive blacks who escaped from slavery in the South.

Sophia Rightmer and Jen Tzetzo

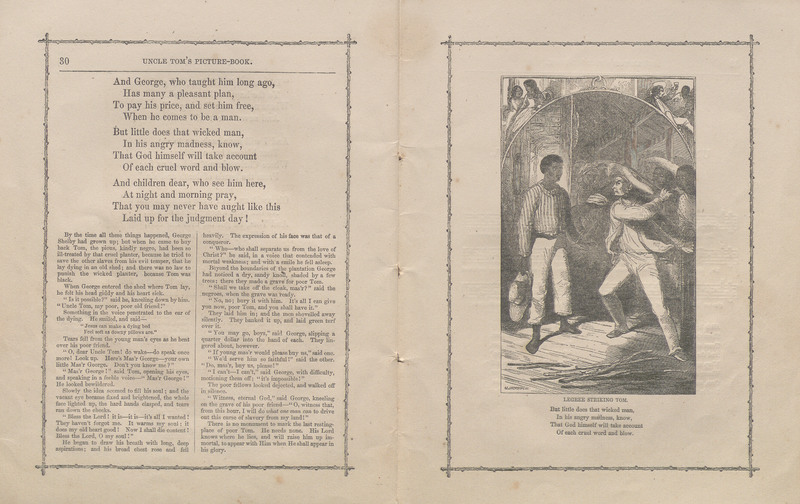

Published by John P. Jewett and Company in 1853, the original publisher of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin found an audience in part because of increasing rates of literacy in the mid-19th century. Born in 1811 in Litchfield, Connecticut, abolitionist writer Harriet Beecher Stowe was a massive influence of her time. Uncle Tom’s Cabin solidified the moral backing of abolition in the North and painted Slave traders as villains, further isolating and angering Southerners. It is widely accounted that when President Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1862, he remarked "So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war."

To create a more “kid friendly” version, of Beecher Stowe’s text, certain elements of the original book were either omitted, or subdued. In the original novel, slavery’s violence was brutally depicted through sexual acts, starvation, and beatings. he adapted version did include beatings, as in the pages shown here, in which an irate plantation worker is preparing to beat Tom with a whip for refusing to punish others and aiding runaways. This pagespread also shows other scenes from the story, such as Harry and his mother relaxing after escaping and the final sale of Tom to his final owner, Legree. Overall, though, the text and illustrations of Pictures and Stories from Uncle Tom’s Cabin is much less graphic than the original. Along with images, specific kid-friendly portions of the text were bolded and enlarged to be read aloud to children and even a song about one of the story’s protagonists Eva is included at the end of the book. This children’s version highlights the abolitionist fervor of the North adapted to reach a younger audience.

Brendan Doyle, Will Overland, and Kurt Schwartz

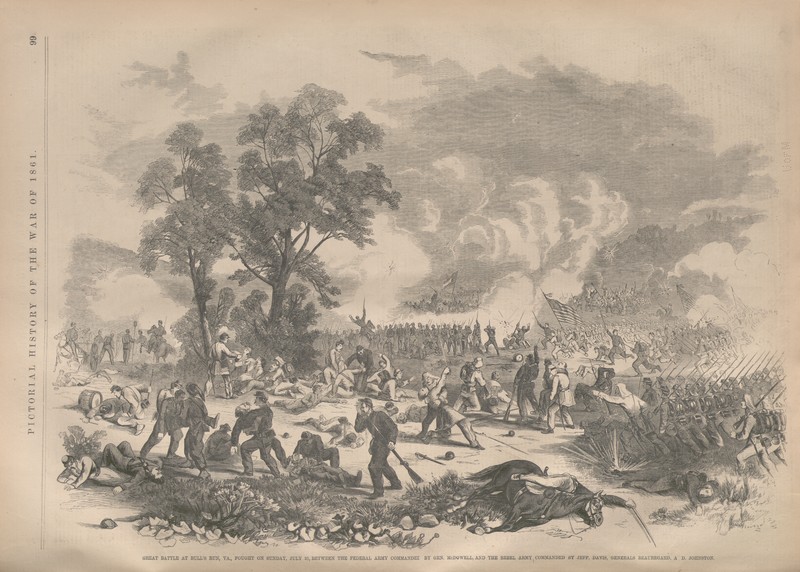

Frank Leslie's Pictorial History of the American Civil War was published in 1862 by Frank Leslie in New York. This illustration depicts the Battle at Bulls Run in July of 1861. In the background are multiple groups of men fighting, surrounded by large clouds of smoke. In the foreground there are more detailed images of dead soldiers and horses sprawled out, and injured soldiers being carried away. It is a chaotic scene. This was only the second year of the war, and is right when the conflict began heating up. The illustration shows the use of a wide array of weapons. There are men with sabres and guns rushing towards each other. The plumes of smoke could be the work of cannons which were frequently used during the Civil War. Prior to this battle, the Union was very confident in their chances against the South, which is shown through their aggressive charge towards Confederate soldiers. In the end, however, the South achieved a morale-boosting victory. The disorderly nature of the photo with the injured soldiers scattered across the ground, and the multiple fights occuring at once portrays the struggle which would ensue during the Civil War. The Battle at Bulls Run was one of many bloody and costly fights of the American Civil War.

Thomas Gaffney and Sam Nahass

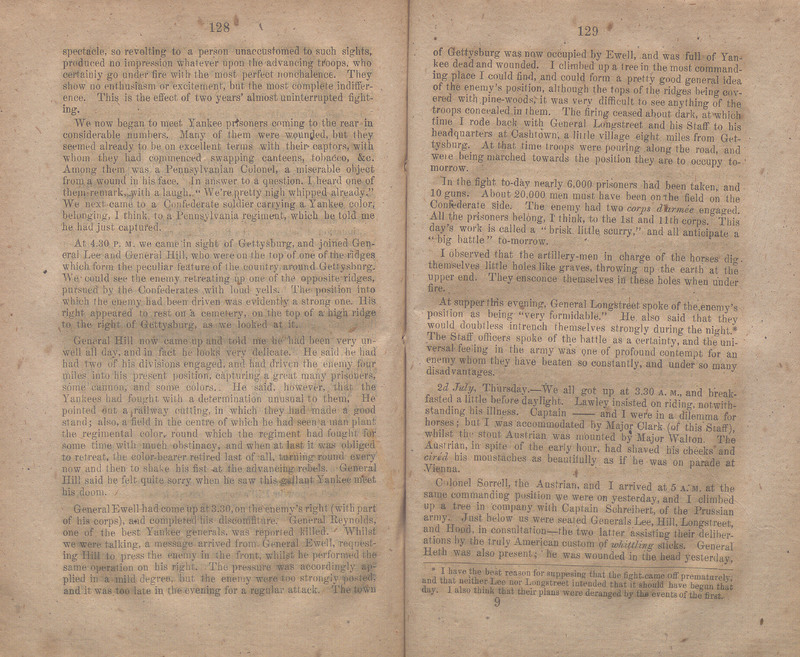

Published in 1863, Three Months in the Southern States gives the account of Sir Arthur James Fremantle’s tour of the South amidst the American Civil War. It tells a gripping tale of wartime travel to an intended audience of both Northern and Southern Americans seeking further insight into life on the frontlines. Fremantle also writes for his fellow English civilians back home who crave information about the conflict overseas.

Though Fremantle began his journey slightly favoring the North, as most of the English disapproved of slavery, he developed strong friendships with Southern Commanders such as General Longstreet and General Lee. His writing offers insight into Longstreet’s and Lee’s mindsets during the war, and also reveals Fremantle’s own shift in perspective about the supposed evils of the South. On display is a pagespread including Freemantle’s description of the Battle of Gettysburg. Here, Fremantle describes a few specific Confederate war tactics, such as a joint attack in which General Hill attacked the Yankees from the front while General Ewell attacked from the right. Fremantle also described the devastation wreaked by the conflict, explaining that nearly 6,000 prisoners had been taken, while the floor of the Gettysburg town was littered with Yankee bodies.

India Holland, Leo Krinsky, and Lyla Wotring

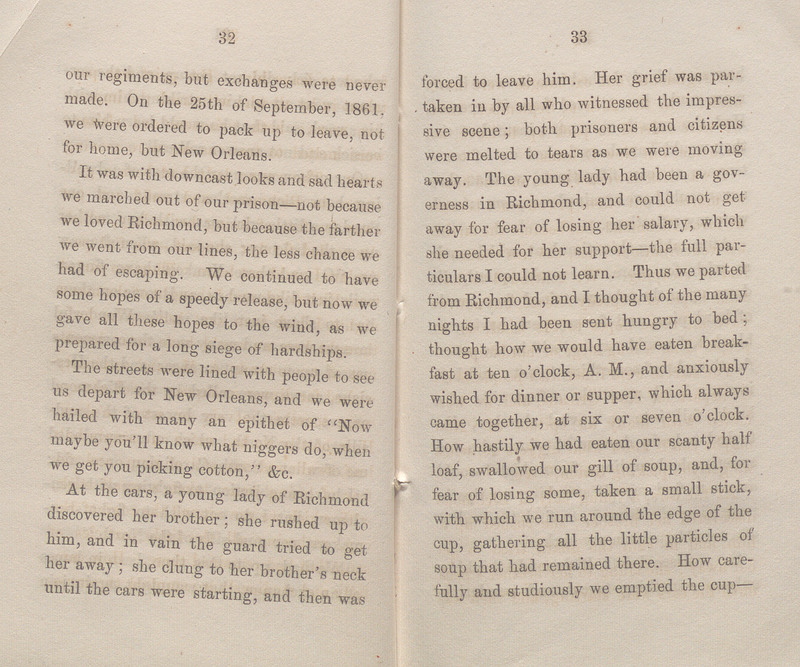

O.H. Bixby was a union soldier captured by the South early in the Civil War. His journal is historically significant because it gives a first hand account of what life was like in a Southern war prison, and how it affected soldiers mentally. For example, they were sad to be moving out of the prison at Richmond even though it was not the ideal living place. However, their despair was warranted because moving farther south meant the time it would take to be rescued would be significantly longer than if they had stayed in Richmond—closer to the Union’s front lines. Bixby writes, “We continued to have some hope of a speedy release, but now we gave all these hopes to the wind, as we prepared for a long siege of hardships.”

Bixby’s account is intended for mainly Northern readers who did not experience what a Southern war prison was like firsthand. It gives the common person a share of the experience he went through. From going to bed hungry, to receiving hateful comments from Southerners in the streets and beginning to treat a war prison like home, the book helps the common person understand what life was like in a Southern war prison.

There is no illustration on the page, but what the reader should take away from these two pages are the feelings the writer portrays. One can really get a sense of how he feels about his journey through the military prison, and how it has changed his perception of surviving.

Grace Clemens and Walker Cleveland

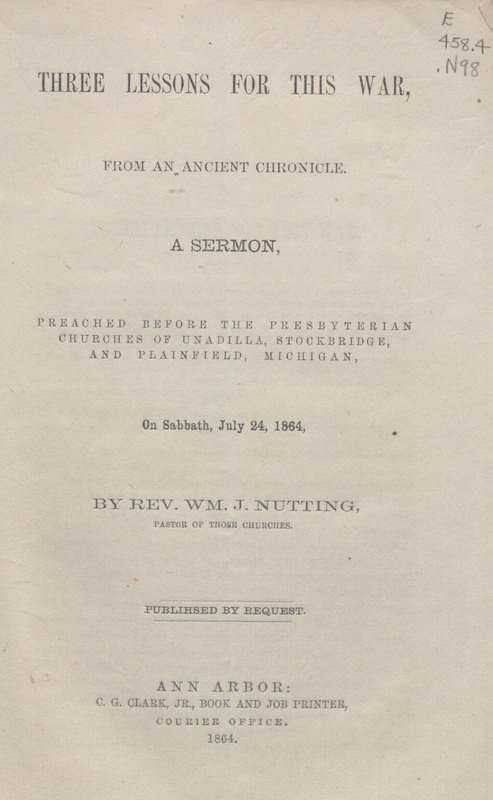

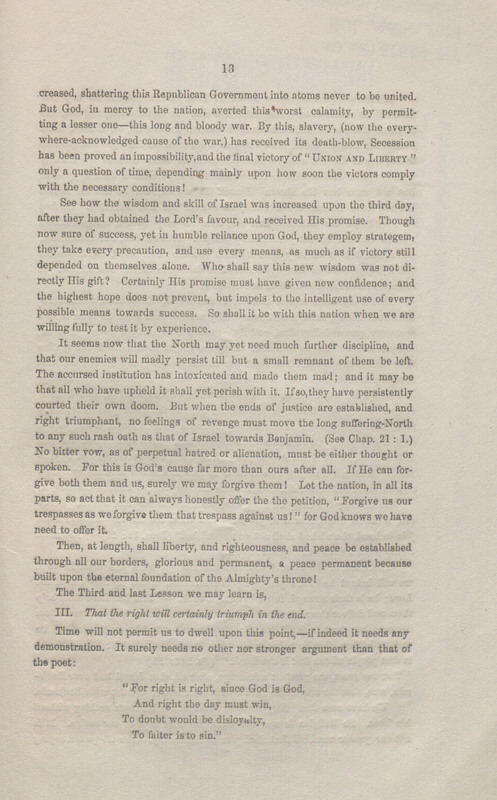

Displayed is the title page of the printed sermon Three Lessons for This War, as well as a one page excerpt containing Nutting’s concluding explanations of his second lesson followed by the introduction of his third: "The Third and last Lesson we may learn is, that the right will certainly triumph in the end."

Reverend Nutting’s sermon provides lessons to be learned from the Civil War, from the viewpoint of a Northern Presbyterian. From its popularization as an institution, African slavery had been rationalized by white slaveholders using Christianity, but abolitionists also drew on Christian principles to argue against slavery. Nutting’s text showcases the latter perspective in his support for the Union side of the war. His viewpoint is quite specific; as a minister, he has an in-depth understanding of the Bible and how one could use the word of God to argue against slavery and against the Confederacy. He also has a brother that lived in the South for much of his adult life, which probably increased his understanding of the relationship between northerners and southerners.

However, Nutting probably didn’t have to convince many people of his cause in Michigan; the Emancipation Proclamation was enacted about a year earlier, and the tides of the war had already turned mostly in favor of the Union. Although Nutting doesn’t necessarily present new ideas in his opposition, his viewpoint does give us a religious perspective on the ongoing Civil War, and depicts the Union homefront as confident in their moral position and their success in battle.

Brooke Christians and Brendon Haithcock

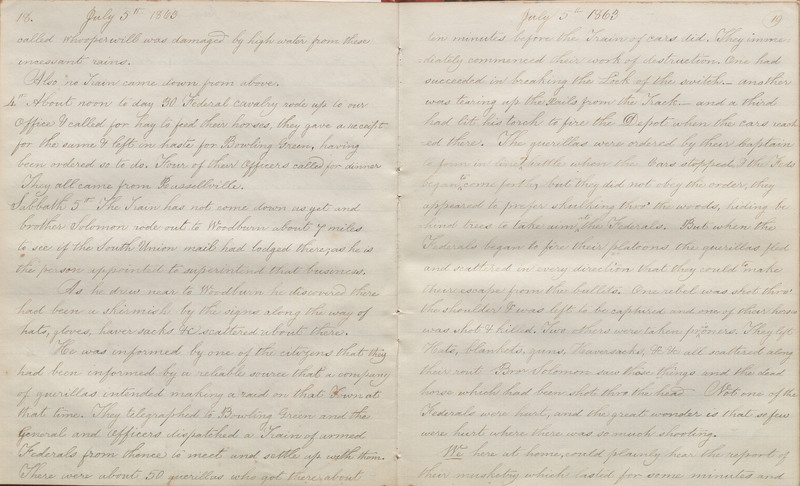

Displayed here is the fourth volume of a set of diaries written by Nancy Ely Moore during the Civil War, from 1861-1865. The pages are a faded yellow with neat, cursive handwriting, that provides a clear, firsthand account of a woman living in Kentucky, a border state between the Union and the Confederacy.

Kentucky had decided to remain neutral at the start of the war, but Moore’s diary highlights that despite neutrality, Kentucky often saw skirmishes that invaded the local townspeople’s lives. The text especially shows the role that civilians played in the war, as Moore explains on more than one occasion how Union and Confederate troops rode in on horseback and took corn and other crops from the farmers who lived in her town. This represents the emergence of total war, where the line between combatant and civilian was erased, as the everyday citizen increasingly was confronted with combat and the ransacking of their properties by both the Confederate and Union armies. Throughout her diary, Moore refers to the confederate troops as "rebels." Because of its negative connotation, and the general use of the word at the time, this indicates that Moore was a Union sympathizer, and thus most likely did not own slaves.

Madeleine Glasser and Emily Vanhaitsma

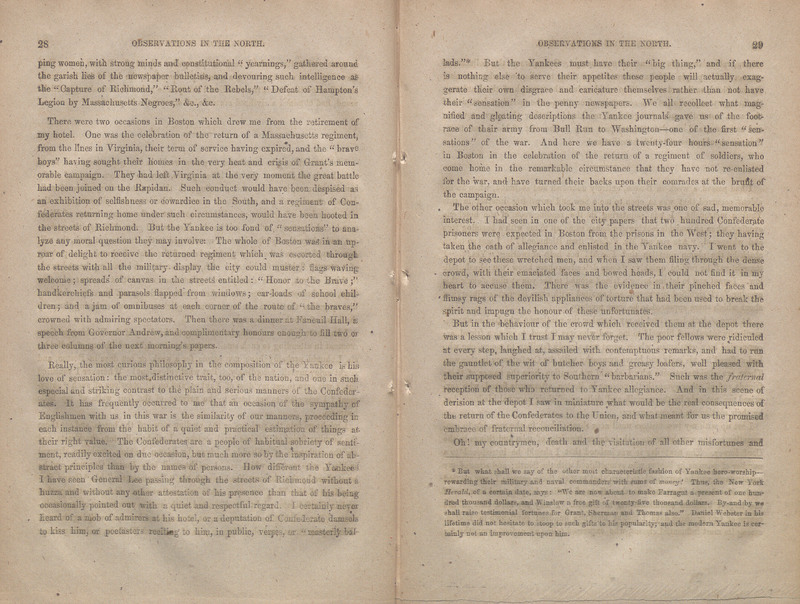

Edward Alfred Pollard was a pro-slavery lawyer, journalist, and writer, who wrote a book recounting his experiences as a confederate soldier captured by the North. In his book, Pollard expresses his fears concerning the Confederacy rejoining the Union. Published soon after the war ended, Observations in the North reaches out to Southerners to address their current feelings towards Northerners, rejoining the Union, and the impending occupation of the South.

Pollard’s fears of returning to the Union are clear on this page spread, where he writes: “The poor fellows were ridiculed at every step, laughed at, assailed with contemptuous remarks... And in this scene of derision at the depot I saw in miniature what would be the real consequences of the return of the Confederates to the Union, and what meant for us the promised embrace of fraternal reconciliation.” Encouraged by Pollard’s writings and other such works, many Southerners, having lost the war, began resisting what they saw as Union occupation. Pollard’s writing exemplified and stoked Southern anxieties about maintaining their culture, way of life, and independence as the war drew to a close and the Reconstruction era began.

Laura Scerbak and Nick Tilson

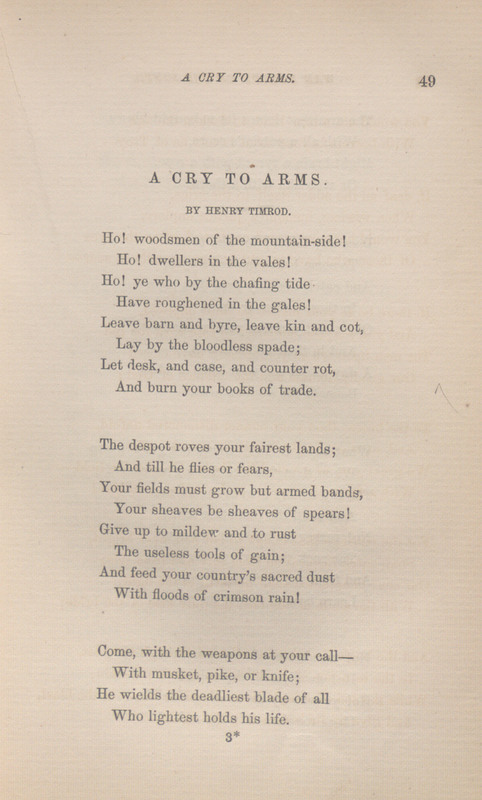

This collection of Confederate poetry was published the year after the end of the Civil War. In the poem on display here, Henry Timrod begins with a call to many different people evoking the imagery of the Southern landscape. A metaphor of the lily fighting a storm serves as a symbol for battle and evokes a fighting spirit.

Timrod’s poem is a literal cry to arms for the young men of the Confederacy with this poem. He begins his work by calling upon people from all regions of the Confederacy to lay down their lives and enlist. He tells men to abandon “kin and cot” to join the cause, acknowledging the sacrifice of leaving home to fight in a distant war. Additionally, Timrod takes aim at the Union, using careful propaganda to paint them as the enemy by referring to them as “the Despot” invading the South.

This piece was first published in a South Carolinian newspaper in 1862. During 1862 the Union achieved two major victories within two weeks of each other: the capturing of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. These two victories secured control of the Tennessee and Columbia rivers, cutting the South off from major waterways. Timrod is responding to these two big blows to the war effort, calling for “floods of crimson rain.” This deliberate work of propaganda is designed to light the fires of the Confederate public.

It is interesting to note how criticism on Timrod’s poems has developed over time. Timrod found little success reaching Union audiences after the war, begging the question of how Confederate contributions to literacy should be viewed in today’s society. Viewed by some as the “poet laureate” of the South, how does the elegance of Timrod’s work conflict with the antiquated and racist nature of his views?

Nicholas Baron and Brandon Burkhardt

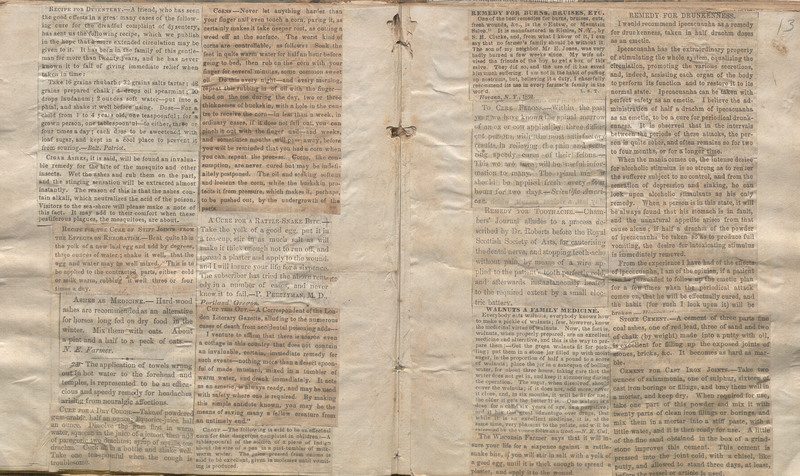

Food and Drink

About the Exhibit