The Qur'an: Functional formats

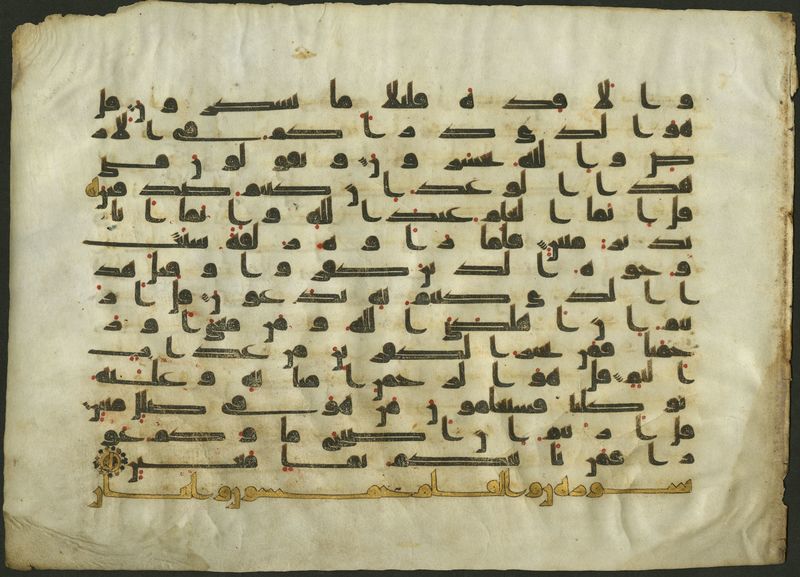

By the year 1000, paper had been accepted as a suitable medium for the Qur'an. A shift back to vertical formats seems to have accompanied the transition from parchment to paper, suggesting that the vertical format was better suited to the new material. More quickly and inexpensively made and prepared for use, paper facilitated an explosion in book production and ownership (encompassing the Qur'anic codex and beyond) that continued through the early modern period.

The intervening centuries saw the development of a range of cursive scripts, as well as new and increasingly sophisticated illumination and binding styles. The significance of reading and reciting the Qur'an as a key observance of Islamic piety and devotional practice fueled the effort that went into multiplying copies.

Throughout the manuscript period, the Qur'an appeared in a wide number of formats that were precisely suited to particular devotional functions. These included enormous presentation copies for communal settings, pocket-sized copies for personal devotion, miniature copies for protection, and multi-volume sets or slender volumes of select chapters for communal or individual recitation.

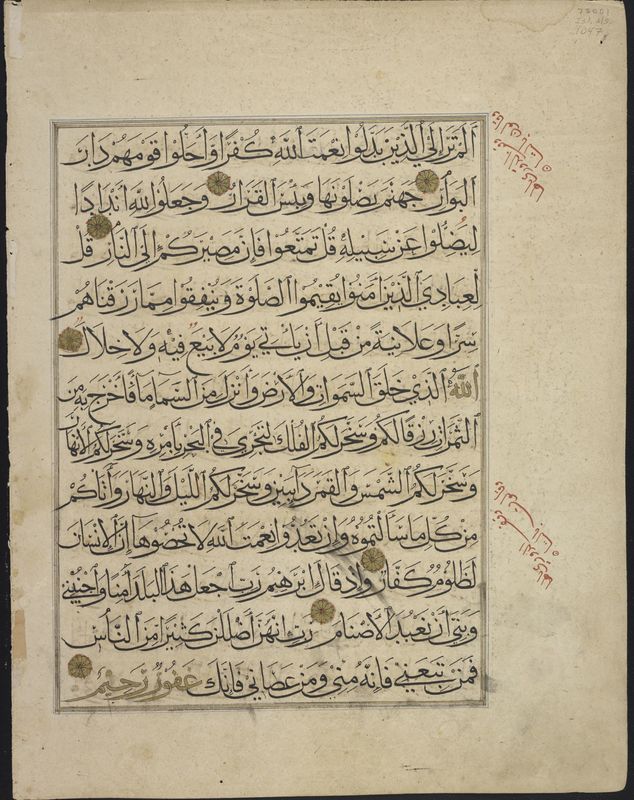

The monumental size of this opening manuscript (Isl. Ms. 1047, above) recalls the Qur'an codices -- many far larger than this codex -- commissioned by rulers of the Īlkhānid dynasty, as well as their contemporaries and successors, for mosques, royal complexes, and other communal settings. The text is penned in a carefully executed and fully-vowelled muḥaqqaq, a stately rectilinear script that emerged as one of the new proportioned scripts traditionally affiliated with the writing reform of Ibn Muqlah (d.940) and refined and standardized by Ibn al-Bawwāb (d.1022). Established as a bookhand by the 13th century, muḥaqqaq was especially favored by Mamlūk calligraphers and others of the mid-13th to 15th century for transcription of such large-format copies of the Qur'an. Amid the usual functional decorations marking various verse divisions, instances of the Most Beautiful Names of God including الله (Allāh, God the one and only), غفور (Ghafūr, the Very Indulgent who pardons much), and رحيم (Raḥīm, the Compassionate) are written in gold.

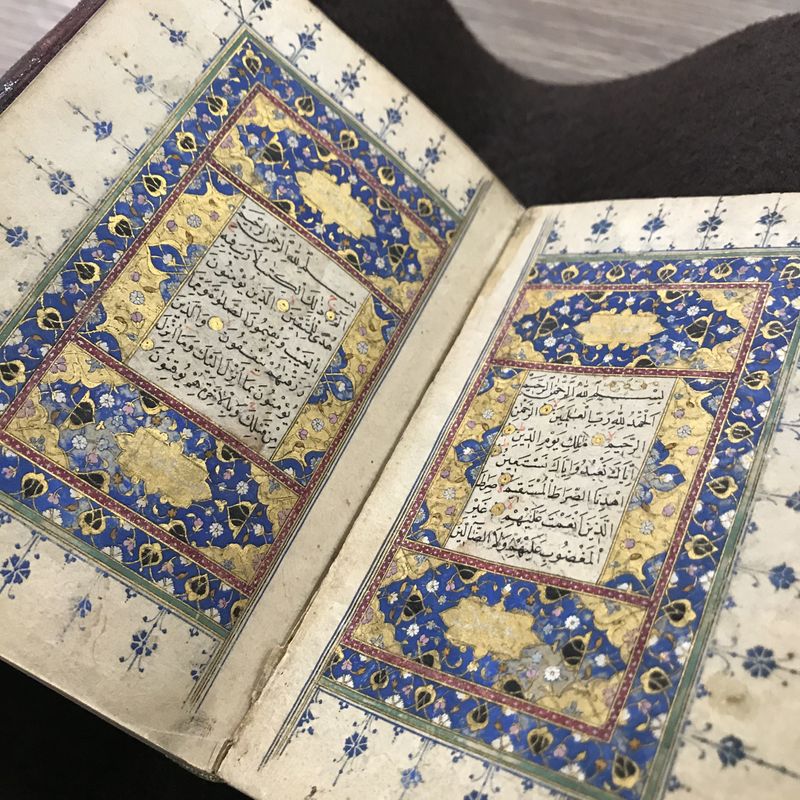

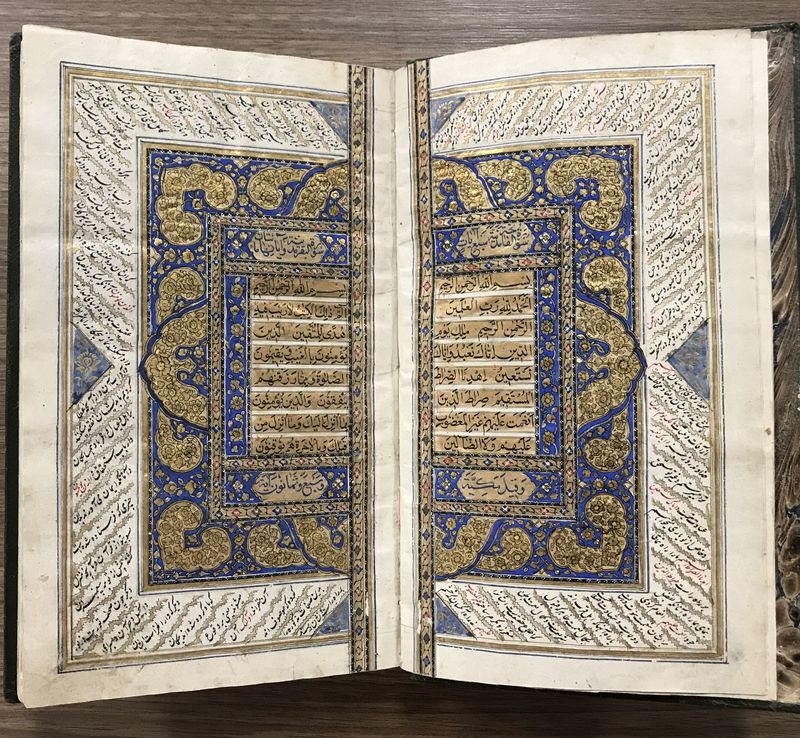

Very small manuscript copies were also produced. Among 17th and 18th century Ottoman elites, the intimate and affordable pocket-size (Isl. Ms. 168, above left) was incredibly popular. This format readily facilitated memorization and recitation in personal devotional. The miniature format (Isl. Ms. 1067, above right) permited a protective intimacy with the physical manifestation of the revealed word of God through wearing or carrying on the body as an amulet or talisman. In the Ottoman era, such miniature copies were also hung from the finials of military standards or banners carried by soldiers during processions and campaigns.

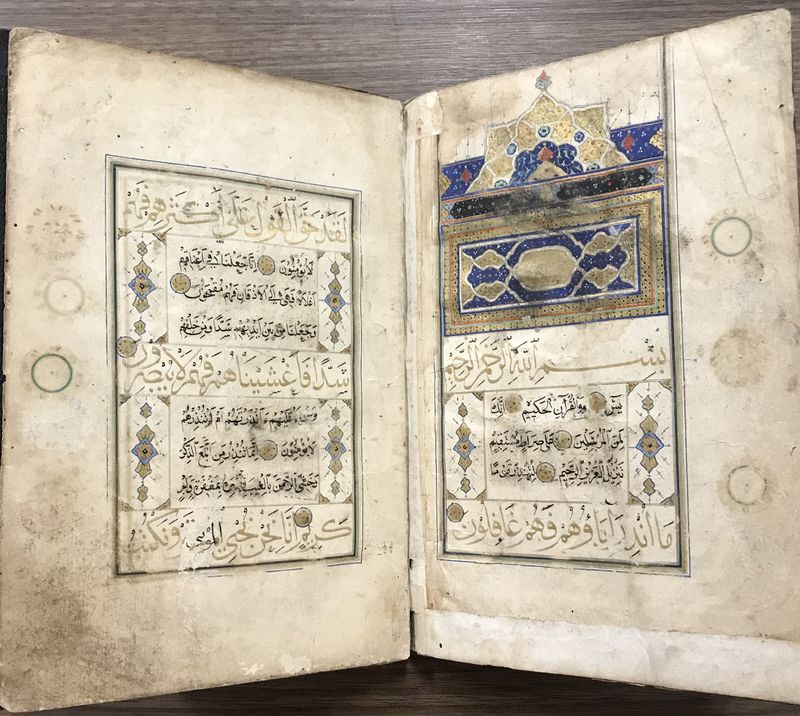

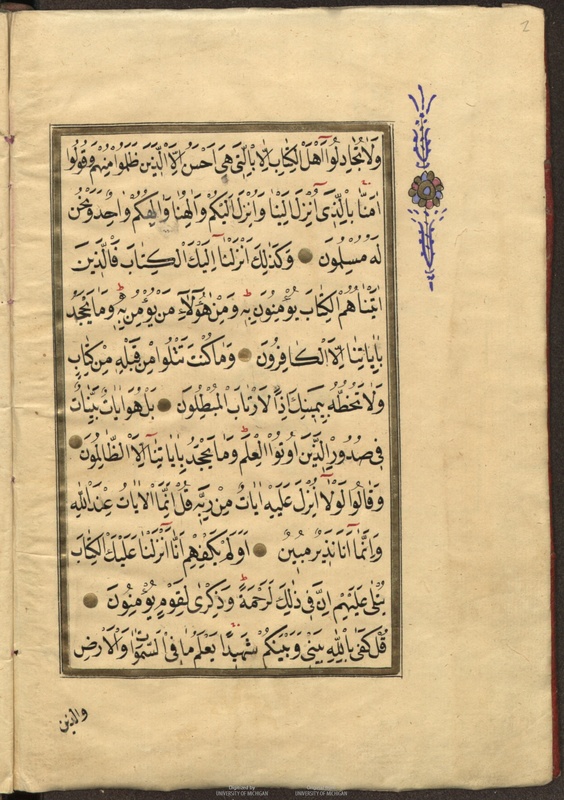

Volumes of select sūrahs (chapters) were also produced, suited to the practice of reciting these sūrahs on particular occasions. The 14th century traveller Ibn Baṭṭūṭah (d.1377) describes such an occasion, held daily in Tabriz in the courtyard of the mosque following the ʻaṣr (afternoon) prayer, in which sūrahs 36, 48 and 78 were read (cf Déroche 2006 p182). Manuscripts such as Isl. Ms. 231 (above) were likely produced in direct response to the demand generated by the development of these devotional practices. Further, these slender volumes -- though ornate, with multiple calligraphic styles and illumination -- made it possible for the less affluent to personally acquire a more affordable partial copy of the scripture. Such manuscripts were very popular in Turkish-speaking areas. The copy featured here carries inscriptions in Ottoman Turkish added by later owners at the opening and close of the volume.

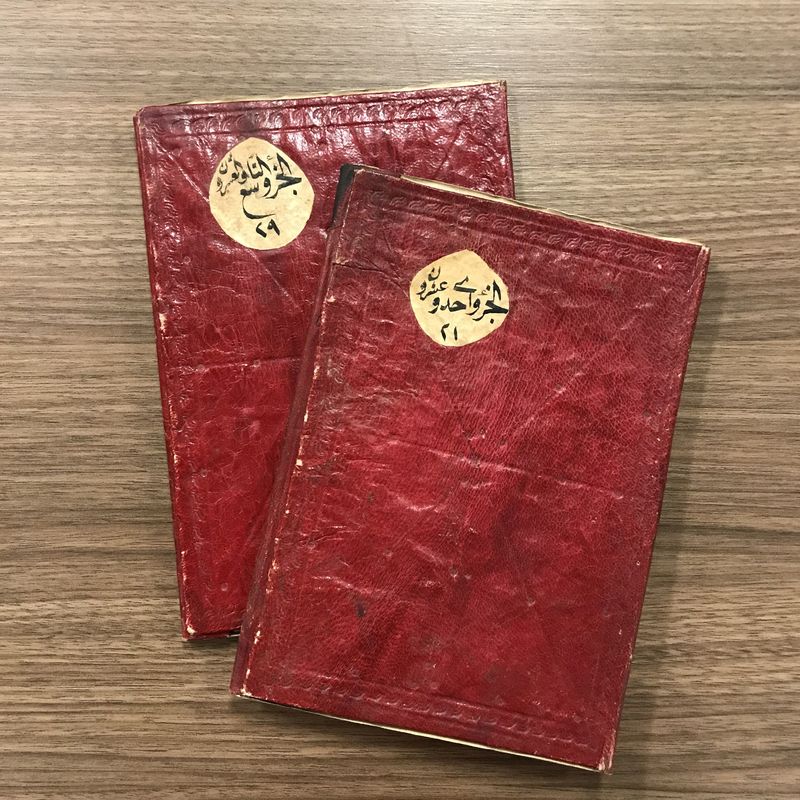

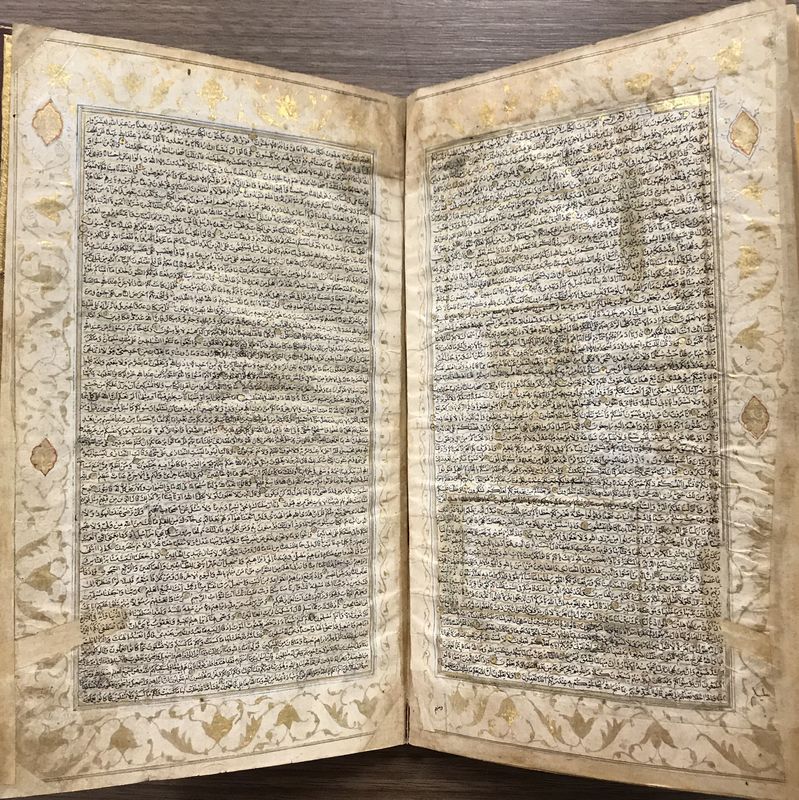

Multi-volume formats such as the thirty-volume set that included the two volumes above (Isl. Ms. 2 and Isl. Ms. 3) facilitated individual and communal recitation that might take place at the tomb of a ruler or a common burial site for the deceased, at a mosque on each night of the month of Ramadan, etc. The format makes it possible for each portion to be easily distributed among reciters or for a single reciter to easily take up the next section for recitation.

Another distinctive format presents the entire Qur'anic text in only a few folios. After the Fātiḥah, each double-page opening presents an entire juz’ (30th) of the Qur'anic text in 51 lines calligraphed in a small script. Quite popular in the Iranian world and India, this format supports recitation by juz’ such as practiced daily during the month of Ramadan. The volume featured here (Isl. Ms. 169, above) was likely produced in Iran or India in the late 17th or early 18th century, then later brought into an Ottoman collection where it was repaired and rebound.

The Qur'an: Early transcription

The Qur'an: Diversity in artistry