The Greek Bible

Jewish disciples and followers of Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified by the Romans around 30 CE, dramatically reinterpreted the Hebrew Scriptures through the lens of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, the Messiah, that is, the savior of Israel and the world. This revolutionary new interpretation materialized in the twenty-seven books of the New Testament, written in the so-called literary Koine Greek, a form of post-classical Greek used during the Hellenistic era, the Roman Empire, and the early Byzantine Empire. Briefly, the New Testament consists of three distinctive parts: the Gospels, which is the story of Jesus as told by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; the Letters or Epistles by Christian leaders to give religious guidance to the early Christian communities; and the Book of Revelation, or the Apocalypse of John, a prophetic account of the end of the world.

It is very plausible that the Christian Bible played a crucial role in the adoption of the codex as a book format by the early second century CE. A codex is a rectangular block of manuscript text with separate leaves hinged along their left or right margins so they can be turned in succession to follow a text from beginning to end. In other words, like a modern book! One of the many explanations for this crucial development in book history is that the Epistles of St. Paul, edited about 100 CE, was such a large compilation that it would have been impossible to include it in a single scroll.

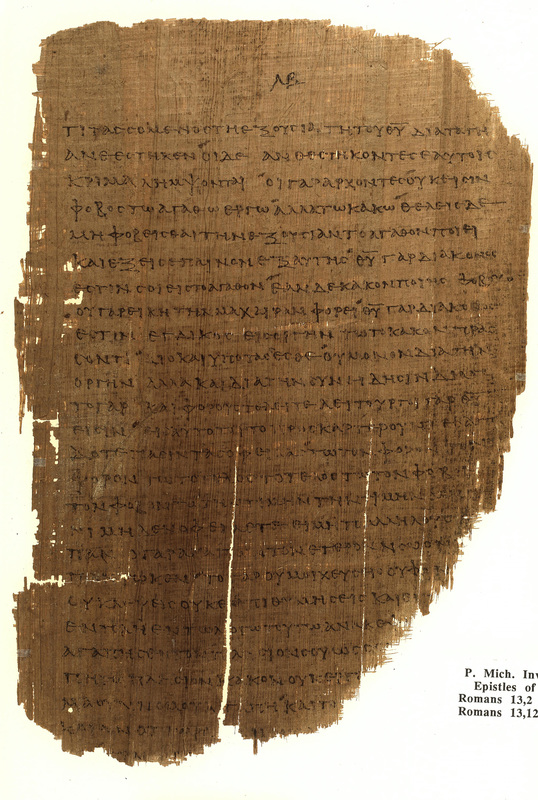

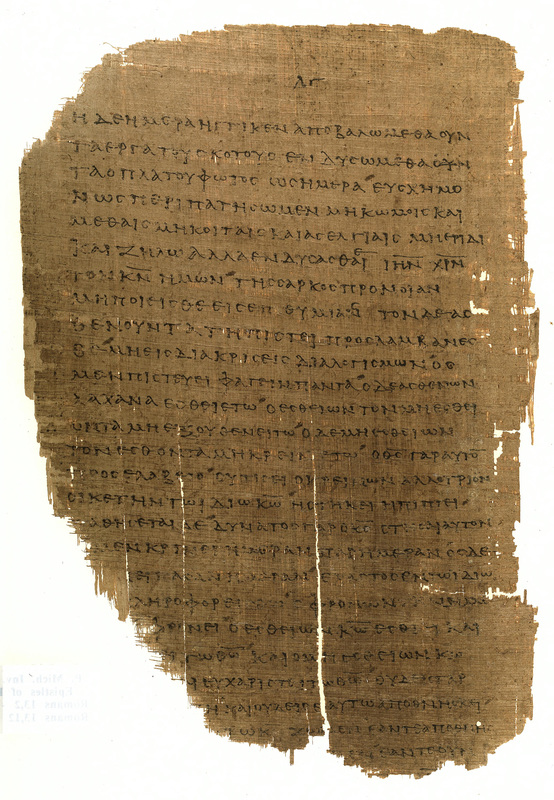

The two images displayed above (P. Mich. inv. 6238, p. 32 & 33) describe a papyrus leaf (recto and verso), part of a thirty-leaf section of a codex that contains the Epistles of St. Paul. They are written in a beautiful hand that can be dated from the late second to the fourth century CE, making this codex the oldest known copy of the Epistles of St. Paul.

The regular handwriting demonstrates the work of a skilled professional scribe, giving each letter the same amount of attention. At a later moment, a reader went through the text and added reading marks above the line in a slightly darker ink than the main text. Although the precise purpose of these readings marks is not clear and they are placed fairly irregularly throughout the text, they must have aided the reading of these verses in church: as it is usual for such early manuscripts, there are no word or sentence divisions in the text and the reading marks are placed where there are clear sense divisions.

The group of letters with a horizontal line above them are the so-called nomina sacra (sacred names). In Christian manuscripts, the names of Jesus, the Lord, Holy Spirit, and so on, were not written out in full, but only with the first and last letter. For instance, the nomen sacrum, ΘῩ, that is, θεοῦ, can be found throughout these two pages.

Vestiges of what was the gutter of the binding of this codex can be seen on the left and right hand sides of the recto and verso pages respectively. Readers would turn the pages of the manuscript on the opposite side, explaining the damage on that side of the leaf.

The complete codex (in New Testament scholarship commonly referred to as P46) must have contained 104 leaves. Of these, eighty-six leaves are extant: thirty are at the University of Michigan (purchased in 1930/1931), and fifty-six are housed in the Chester Beatty Collection of Dublin, Ireland.

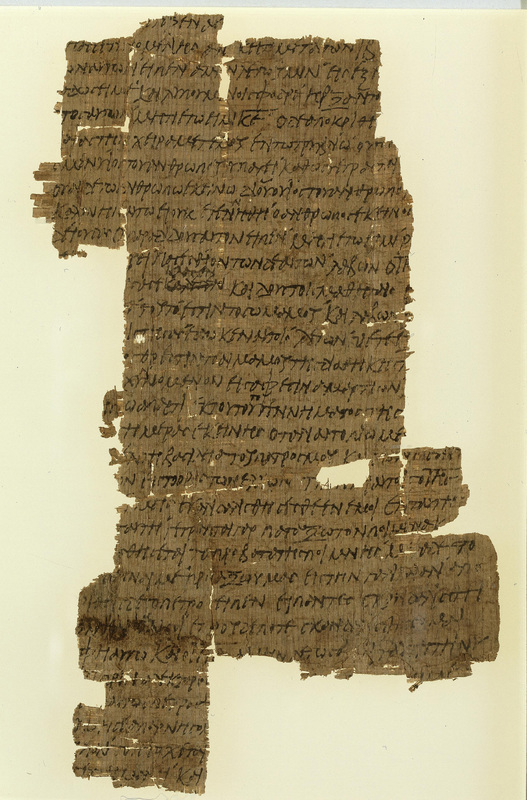

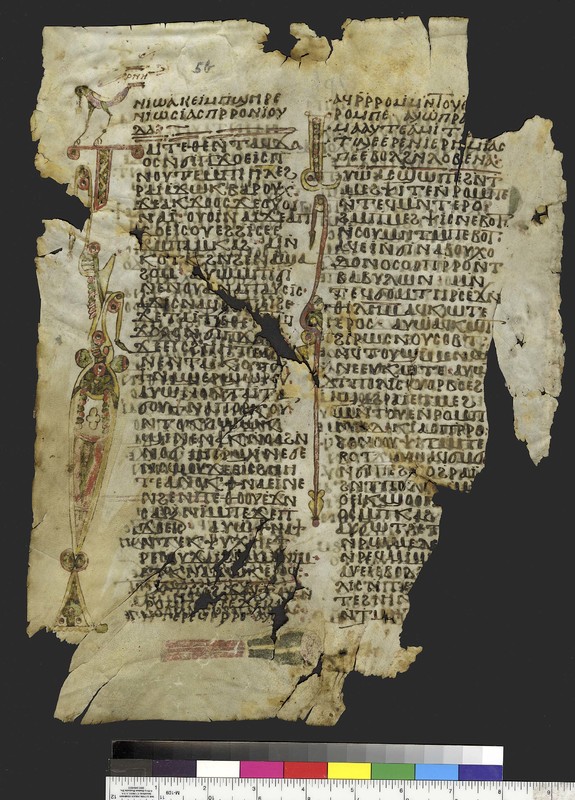

This recto of this heavily damaged papyrus leaf shown above, P. Mich. inv. 1570, contains Matthew 26:19-37, detailing the Lord's Supper. The verso contains Matthew 26:37-52. The handwriting is a regular but not very elegant cursive. It is the work of somebody used to writing, but not of a professional scribe of literary texts. At a later moment someone added diagonal dashes to the text, possibly, reading marks for reading in church.

The text is revealing for the early manuscript tradition of the Gospel of Matthew. It provides a number of readings not known from later traditions. A remarkable scribal mistake is clearly visible in line twelve from above, where the scribe first wrote "he called [the bread]," but then crossed this out and added the correct "he broke [the bread]" above the line. In Greek, the diference between these verbs is small: ἔκαλεσεν (called) ἔκλασεν (broke).

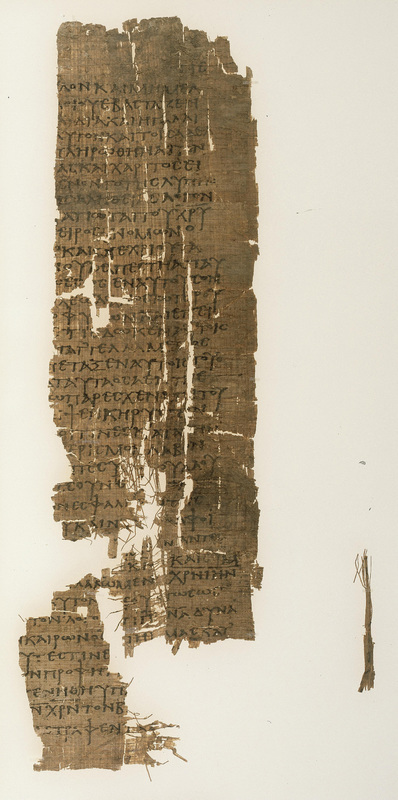

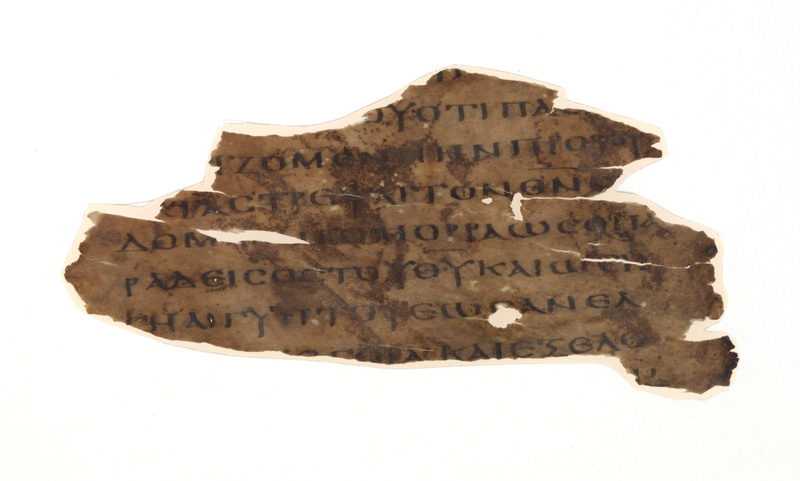

The papyrus fragment displayed above, P. Mich. inv. 1317, preserves the final lines of a page containing the Acts of Paul. This apocryphal work, composed in the late second century CE, describes the life, deeds, and martyrdom of the apostle Paul. This particular passage deals with Paul's arrival in Italy, on his way to Rome, where he is received in the house of a certain Claudius and gives a speech to the people present there.

The text is written in a formal book hand of considerable care that is known as the "severe style." In the right upper margin, the page number 85 (ΠΕ) is visible.

This papyrus was purchased by the University of Michigan as two separate fragments in 1924 and 1925. The beginning of the lines that are missing in this papyrus are preserved on a fragment acquired by the Berlin Papyrus Collection in 1925.

In his Epistles, St. Paul, like other earlier Christians, quoted the Old Testament by using the text of the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures originally undertaken in the third century BCE. The legend of the origin of this translation is based on the “Letter of Aristeas”, a Jewish court official under King Ptolemy Philadelphus, who reigned Egypt from 285 to 247 BCE. According to Aristeas, the king commissioned seventy-two Jewish scholars the translation of the Torah or Pentateuch to be included in the library of Alexandria. Gradually, over many decades, other books were translated into Greek until the whole Scriptures were translated. Thus, the name “Septuagint”, seventy in Latin, and with the number “two” being dropped over time, designates the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.

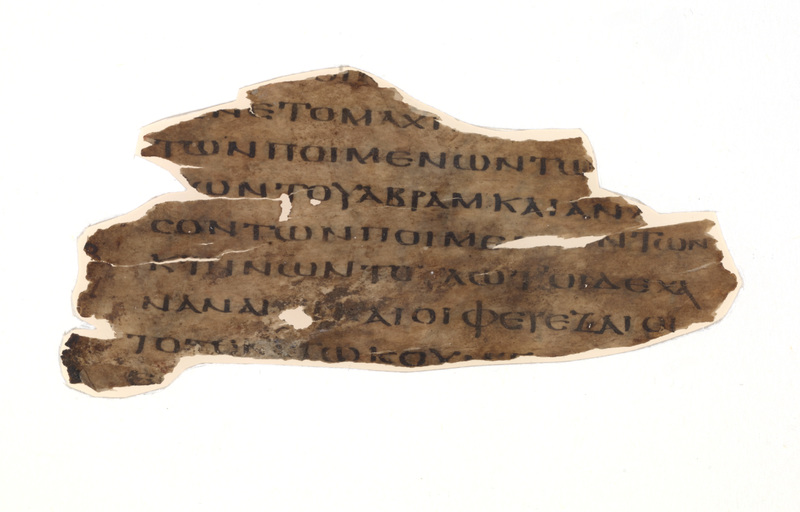

Above is a small parchment fragment, P. Mich. inv. 2724, containing some Greek lines from the Septuagint: Genesis 13:7-8 on the recto and 13:10 on the verso. Each page of this codex must have contained between twenty and twenty-three lines with eighteen to twenty letter per line. Judging by the extat fragments, Genesis was after the Psalms, the most popular Old Testament text in Egypt. The text is written in a beautiful book hand with characters that are very evenly spaced.

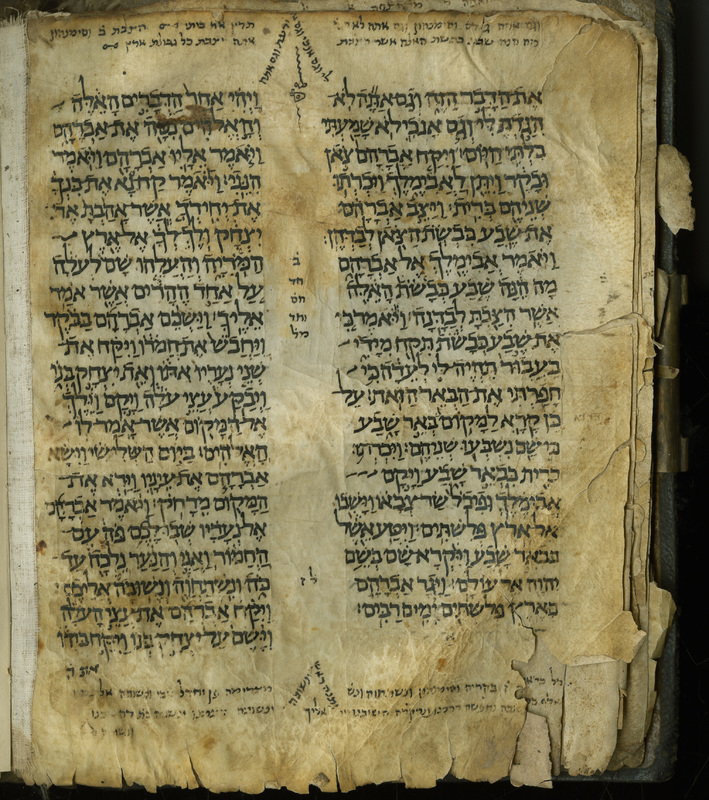

The Hebrew Bible

The Bible in Coptic