The Latin Vulgate

St. Jerome translated the Old and New Testaments from Hebrew and Greek into Latin at the end on the fourth century CE. Jerome was not only a translator but a diligent editor, using numerous manuscripts of the Scriptures in their original language and in old Latin translations. For instance, he excluded the books that had been already rejected in the Hebrew Bible, that is, Baruch, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Tobit, Judith, and I-II Maccabees, describing them as "apocryphal", which literally means "hidden." In other words, they became the "hidden books" to be separated from the authorized Bible. However, Jerome's extraordinary work of scholarship would be betrayed by subsequent generations of readers who gradually inserted back old inaccurate Latin versions of the books rejected from the Hebrew original. The final result is what we know as the "Vulgate", or popular version, a monumental Latin Bible that was not authored by Jerome alone. With some variants between copies, this is the version used in the Christian West throughout the Middle Ages.

For centuries, the text of the Latin Vulgate was materialized in a particular manuscript layout depending on its purpose and audience. Put differently, the content and shape of biblical manuscripts of the Vulgate reflected their use in various educational and religious settings. For example, in the first half of the twelfth century the demands of the cathedral schools were met by the introduction of a new biblical commentary known as the Glossa Ordinaria.

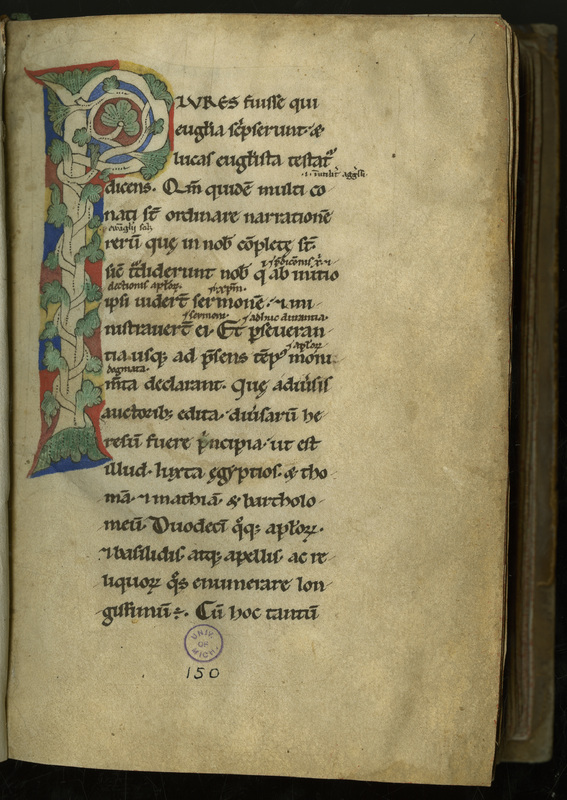

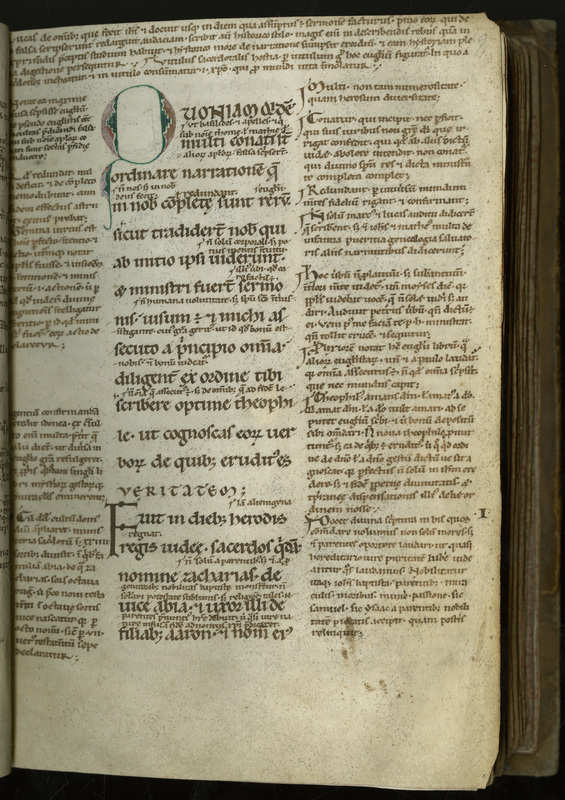

Mostly compiled by Anselm of Laon from the writings of the authorities of the Church, such as Jerome, Augustine, and Cassiodorus, the Bible with the Glossa Ordinaria, or Gloss, spread all over Europe from the French cathedral schools. Shown above is the first folio of a twelfth-century manuscript of the Gospel of Luke with the Glossa Ordinaria (Mich. Ms. 150). This first page displays the beginning of Jerome's Preface to the Four Gospels, opening with the decorated initial "P."

As displayed in the layout of our manuscript above, the main text was displayed in a central column, with the Gloss written in a smaller script and arranged on both sides of this central text and in between the lines of the biblical text. Obviously, the text of the Vulgate could not be comprised in a single volume but was distributed in dozens of volumes containing one or two books of the Bible with their respective commentaries.

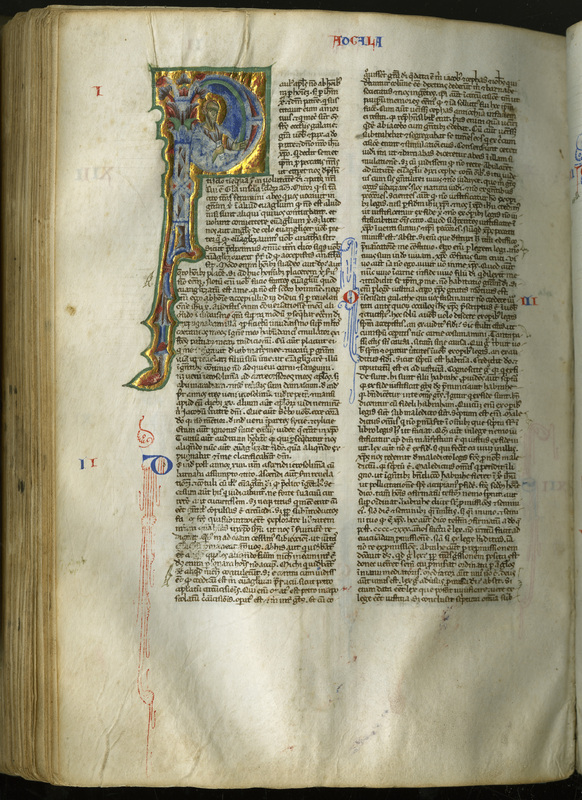

The page of the Bible displayed above (Mich. Ms. 1) exemplifies an important development in how the text of the Latin Vulgate was presented in the thirteenth century. We are referring to the massive appearance of the single-volume portable Gothic Bible copied on a carefully treated parchment, which resulted in extremely white and thin leaves. Specifically, this Bible was written in two columns with a minute compact and heavily abbreviated Gothic script, and adorned with red and blue headings across the top of the pages, and red or blue small chapter initials often accompanied by waving banners of the opposite color. The ornamentation of the pages also included the occasional large historiated initial exquisitely decorated in bright colors and a gold leaf. For instance, in the image above see the initial "P", depicting St. Paul holding a scroll, and opening St. Paul's Epistles to the Galatians. The phrase "Paris Bible" to designate these bibles was already used in the Middle Ages. It probably acknowledges the role of the Paris schools in adopting the order of the books of the Bible according to the Greek tradition as opposed to the Hebrew Bible.

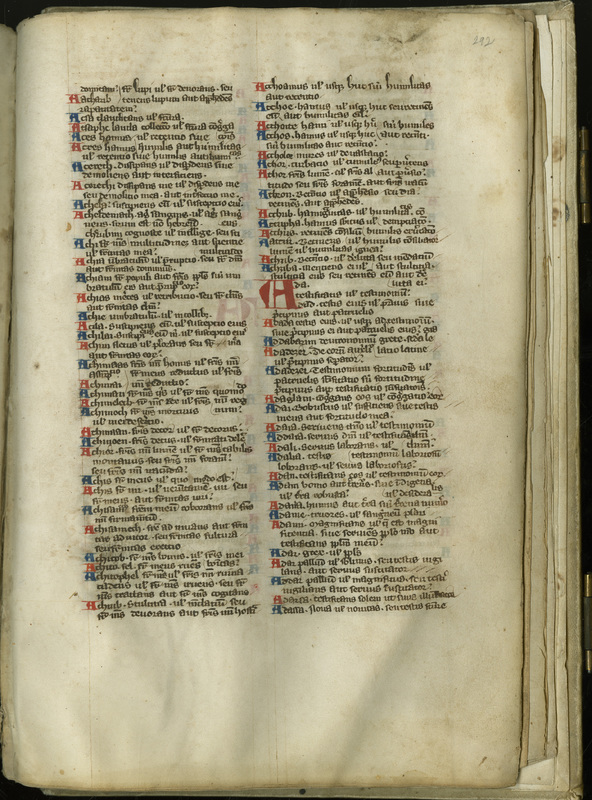

While these bibles include the text of the Vulgate, there are some variations and innovations. Some texts were removed, such as the Canon Tables of the Four Gospels. But others were added, like the glossary "Interpretation of Hebrew Names" (Interpretationes nominum hebraicorum) which was regularly added at the end: see example in the image displayed above. The prologues, which were brief introductions to each biblical book, or to a set of books, acquired a higher status, turning into small books that deserved their own illuminated initials. The Bible was arranged according to a standarized order of books, with the text divided into numbered chapters.

Overall, these standardized bibles addressed the educational demands of universities and schools recently founded across Europe. Moreover, these portable bibles must have served the needs of mendicant orders, like the Franciscans and Dominicans, who had adopted a lifestyle that included traveling and preaching.

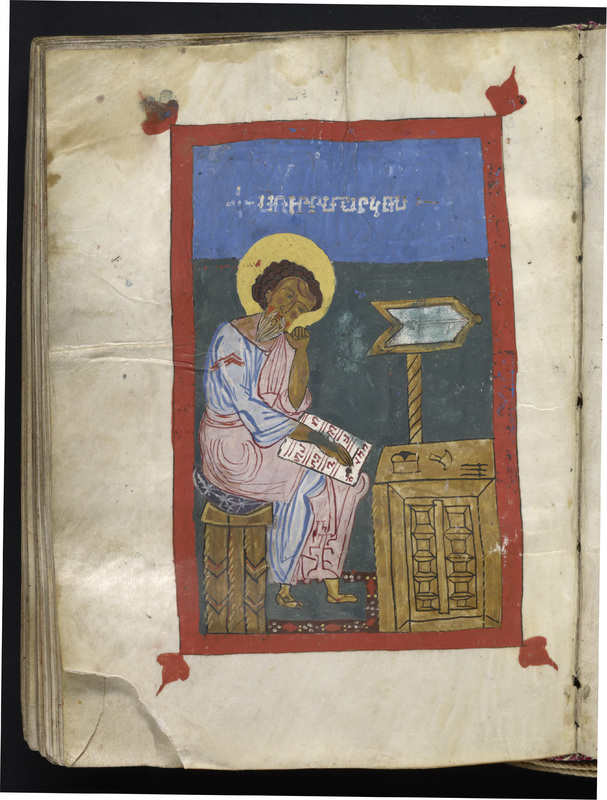

The Bible in Armenian

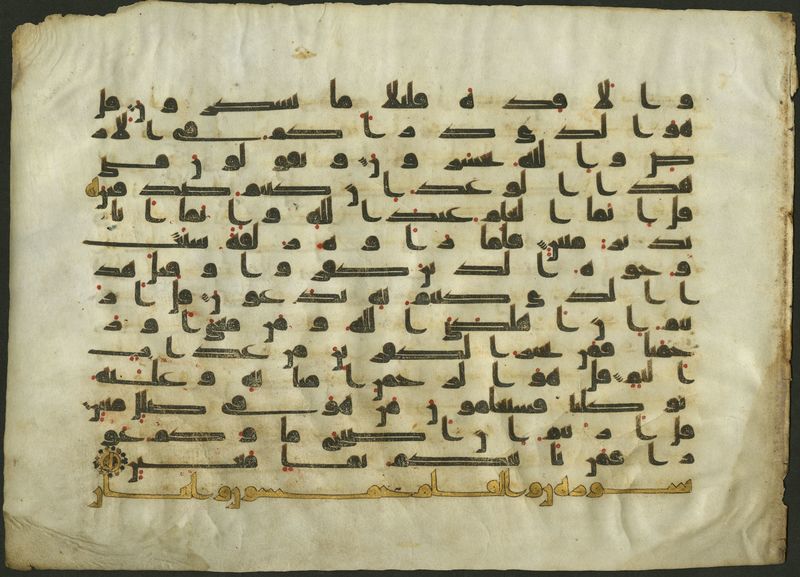

The Qur'an: Early transcription