History

The Low Countries

The 16th and 17th centuries in the Low Countries were tumultuous, but also a period of immense cultural change and prosperity. Since 1477, the Low Countries were under the rule of Habsburg Spain, primarily Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain (1516-1556), and Philip II (1556-1598). Antwerp was expanding into a major center of trade and banking during the first half of the 16th century. This rapid growth had a dramatic effect on the development of the arts and sciences in the Low Countries, particularly the study of geography and graphic art. By 1550, Antwerp, located in the Southern Provinces, had become the second largest city north of the Alps, and the financial and trading capital of the world. The Portuguese used Antwerp as the center of their booming spice trade, as it provided easy access to central Europe's silver and copper mines. The precious metals were necessary to pay for the spices and other goods coming out of Africa and India.

By 1568 growing Dutch discontent reached a breaking point. The heavy taxation and other complaints against the absent monarchs finally led to the revolt of the Seventeen Provinces against their Habsburg sovereigns. Philip II's anti-Protestant fervor took physical shape in the form of the Spanish Inquisition, and his extreme militancy in response to the Dutch revolt led to an all-out rebellion and the beginning of what would later be called the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648). Antwerp was sacked in 1576, beginning the city's downfall as an economic capital. The political and religious upheavals caused many citizens, including printers, artists, and craftsmen, to flee to Amsterdam in the north. The Northern Provinces expelled Spanish control and declared their independence in 1581. While the Spanish control over the Southern Provinces remained strong, Amsterdam saw an "influx of new religious, philosophical, and scientific ideas" (Brotton, p. 267).

While war in the Southern Provinces raged on, the north prospered in their independence as their navy and merchant fleets grew. The first Dutch-led expedition to Java took place in 1595 and seven years later, in 1602, the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (V.O.C.), more commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was founded in Amsterdam. Between its founding and 1660, the highly profitable V.O.C. transformed Amsterdam society. With the V.O.C. offering all Dutch citizens the opportunity to invest in the trading company and in turn receive a share of the profits, the merchant and middle class grew rapidly and became the new ruling class of Amsterdam.

From 1609-1621, a temporary ceasefire in the midst of the Eighty Years’ War allowed the Dutch Republic to rapidly increase the size of their fleet, which ultimately led to Spain’s downfall in the region as the Dutch overtook their trading routes and markets throughout the East. The expansion of the Dutch East India Company into areas previously controlled by the Spanish meant an increased demand for complete and accurate commercial maps. This new need was met with a generation of mapmakers and printers, including the Hondius and Blaeu families.

Brotton, Jerry. A History of the World in Twelve Maps. London : Penguin Group, 2012.

Broecke, M. P. R. van den, ed. Abraham Ortelius and the first atlas : essays commemorating the quadricentennial of his death, 1598-1998. Houten, the Netherlands : HES, c1998.

Making a map: Publishing, Printing, Papermaking

Publishing

The battles waged on the political and religious stages of the 17th century had a direct impact on the publishing world of Amsterdam. There were two distinct periods where Dutch commercial cartography and publishing flourished. The first period, centered in the South Provinces around Antwerp, lasted into the 16th century and accompanied the city’s economic growth and cultural boom. The second, situated in the Northern Provinces, continued through the end of the 17th century and saw Amsterdam supplant Antwerp.

The first wave of prosperity for Dutch cartography in Antwerp was greatly influenced by the nearby University of Leuven. Located about 30 miles south, the university was one of Europe’s great centers of learning and had a far-reaching impact on the development of cartography across Europe. Studying at Leuven, the famous Flemish mapmaker Gerhard Mercator was greatly influenced by Gemma Frisius, the first to publish on the use of triangulation for accurate surveying (Koeman et al., p.1297). It was here where Mercator established his business, the first commercial map production in the Low Countries. During Mercator’s lifetime map publishing grew from being of lesser importance, concerning only academics and printers, to becoming a profitable business and essential economic enterprise (Koeman, p.1299).

The largest publisher at this time was Christopher Plantin whose publishing firm in Antwerp came to monopolize the map business. In 1570 Abraham Ortelius’s atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, first published by Gilles Coppens de Diest and later by Plantin, quickly became a commercial success throughout Europe. With the Theatrum and other important works the Low Countries soon surpassed Italy in map production and the Golden Age of Dutch mapmaking had commenced.

The second period of prosperity in Dutch cartography was underway in the Northern Provinces by the 1630’s, when the maps from our project were printed. By this time Amsterdam had surpassed Antwerp as the largest publisher of cartographic materials in the world. This shift occurred in large part because of the exodus of many of the best engravers and cartographers out of the Southern Provinces. At the same time, the growing demand for maps, both at home and throughout Europe, ensured a robust and stable market. Specific map firms, such as the Blaeu and Hondius families, profited immensely by officially supplying the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (V.O.C.), or Dutch East India Company with maps. The V.O.C. was established in Amsterdam in 1602, and their rapid growth created the need for a great number of maps and sea charts. The company’s distribution networks greatly benefited Dutch publishers, as the V.O.C. could easily move printed works to far flung markets. At the same time each expedition’s return meant vast amounts of new and increasingly accurate geographic information for Dutch mapmakers to incorporate into their maps.

Papermaking

Throughout the course of our project we studied the variations and unique features of the maps’ paper, looking for common attributes. With the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, parchment as a means for printing was quickly replaced by paper. During the 17th century, making paper by hand, or “antique laid paper,” was a multi-step process, with many opportunities for variation or the accidental creation of unique features. In the 1600’s, paper was made from rags, which were broken down, or “retted,” for their fibers. The fibers were then beat into pulp and mixed with water to give the necessary consistency required for the type of paper. A wooden handmould, constructed of wood “ribs” and a screen of metal wires, called “laids,” was dipped into the fibrous water repeatedly, until eventually a fresh sheet of paper would be carefully deposited on damp woolen felt. Subsequently the stacks of paper and felt would be pressed, dried, and eventually “sized”, using gelatin. “Sizing” made the surface of the paper liquid and wear resistant, making it easier to be printed or written upon.

As paper mills operated from Monday to Saturday, paper sizing occurred throughout the week, resulting in what former University of Michigan Library Senior Conservator, Cathleen Baker, refers to as “Tuesday/Saturday paper.” As gelatin spoiled quickly, alum and other preservatives were added to the mixture throughout the week. These additives counteracted the efficacy of the sizing, though, causing the paper to become more absorbent. At the same time, the addition of alum caused the paper to become acidic. Consequently, paper that was sized on a Saturday will often have dark grayish brown discoloration to it.

Watermark

A watermark is a symbol or lettering that becomes visible when the paper is held up to transmitted light. The watermarks were often added by the papermakers and could include the name of the mill or a symbol or crest to represent them. The mark is made by bending a small wire into the required shape, and “sewing” it onto the laids or the metal screen. As the handmould was dipped into the fibrous water, the paper would be thinner over the wire than across the rest of the mould.

Papermaker's tears

Papermaker’s tears are a blemish that can be found in antique laid paper. Once the sheet was pulled from the vat, papermakers were careful to not drip any water onto the newly formed sheets. Should a drop land on the new paper, it forced the fibers apart, causing a small disturbance in the weave of the paper. These “tears” are a thin spot in the paper, but rarely result in a hole.

Printing

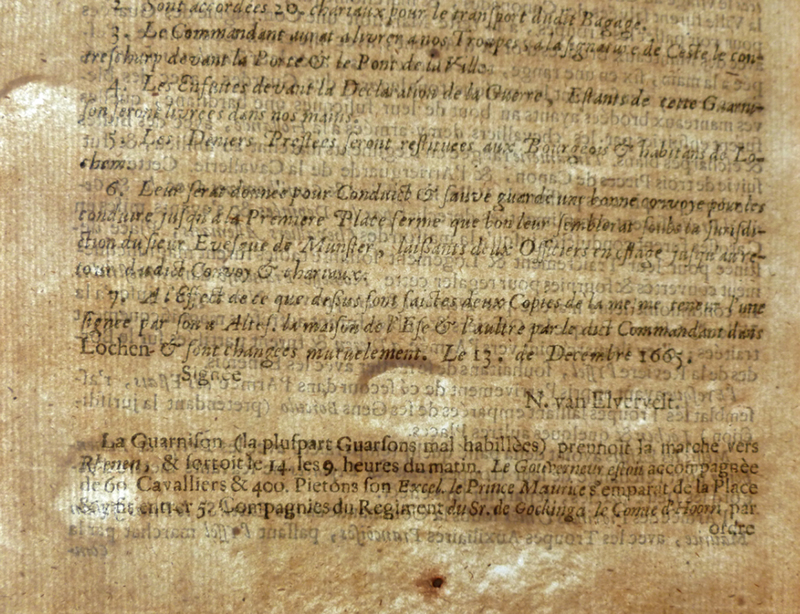

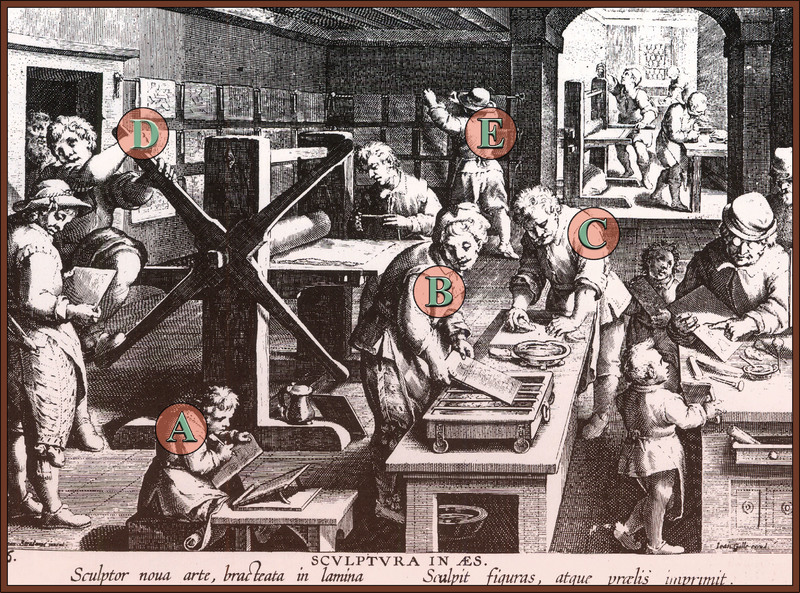

Understanding the map printing process used during the first half of the 17th century was paramount for analyzing the maps throughout the course of our research project. Two methods of printing were common at the time, relief and intaglio. The maps in this exhibit were all printed using the intaglio method and copper plates. The intaglio method involved removing metal from a copper or zinc plate, creating grooves which would hold the ink. One of the advantages of this method was that intaglio engraving allowed for finer lines and rounded lettering, and made for easier correcting as well. One clue to identifying if a map was reproduced using copperplate printing is by finding the indented plate marks, which mark the edge of the plate, and are visible just beyond the map border. Engraving was a highly skilled profession and art form that involved transferring the cartographer’s original hand drawn map to the plate. First, a thin layer of wax was applied to the surface of the plate and then a burin was used to engrave the image into the plate in reverse (see A below). Sometimes, lines from the original map would be transferred to the plate by pricking holes and rubbing chalk through the holes onto the plate, creating a line which would later be engraved.

Before printing, the plate would be heated to help the ink flow freely into the engraved lines and lettering (B). It was then inked and wiped clean so that the ink remained only in the grooved engravings of the plate (C). As it took around 20 minutes to re-ink a plate, other plates were inked simultaneously and made ready to be put on the press once the previous print was finished. The paper was moistened or “sized” to better hold the ink, then laid and pressed onto the plate with great force by the rolling press (D). The freshly printed map was then hung to dry (E) and once dry would be put in a press to be flattened. It was possible to get one to two thousand impressions from a single copperplate, though parts of the image would have to be recut throughout the plate’s life cycle to achieve that many impressions. Some plates would be reworked with updated information or authors’ names (Woodward, p.597).

Broecke, M. P. R. van den, ed. Abraham Ortelius and the First Atlas : Essays Commemorating the Quadricentennial of his Death, 1598-1998. Houten, the Netherlands : HES, c1998.

Koeman, Cornelis, et al. “Commercial Cartography and Production in the Low Countries, 1500-ca. 1672.” From History of Cartography, v.3 pt.2.

Tooley, R.V. Maps and Map-Makers. New York: Dorset Press, 1987.

Baker, Cathleen A. From the Hand to the Machine: Nineteenth-Century American Paper and Mediums: Technologies, Materials, and Conservation. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Legacy Press, 2010.

Verner, Coolie. “Copperplate printing”. From Five Centuries of Map Printing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975.

Woodward, David. “Techniques of Map Engraving, Printing, and Coloring in the European Renaissance”. From History of Cartography, v.3, pt.1.

Maps in the Low Countries

Cartographic Predecessors

While the work of Hondius, Janssonius, and Blaeu is still widely celebrated, it is helpful to look back at the mapmakers and maps that inspired and influenced them. The antecedents of the Hondius and Janssonius maps can be traced back to the portolan (sea navigation) charts, Ptolemaic maps, and local property and legal maps. During the early part of the 15th century, little was known of the world outside of Northern Europe. However, two factors profoundly changed this: the return of the Portuguese voyages of discovery and the reappearance of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia.

Originally published in Egypt by Claudius Ptolemy (100-170 C.E.), Geographia was first translated into Latin in 1406. It revolutionized cartography, allowing cartographers to create atlases with a geographical accuracy previously unknown. The Ptolemaic portrayal of the world was soon supplanted by the influx of new geographic information from the maritime explorations of coastal Africa, South and East Asia, and the Americas. With this new knowledge, atlases evolved into more accurate and standardized publications. In 1570 Abraham Ortelius published what many consider to be the first modern atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World).

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) began as a map colorist and eventually became a book, print, and map seller. Throughout his travels and business dealings, Ortelius made connections with mapmakers across Europe, many of whom provided maps for his Theatrum. Ortelius redrew these maps, in order to have a uniform style and size throughout his work. (Koeman, 319). The Theatrum, published in several languages, was not only the most expensive printed book, but also the most popular atlas of its day.

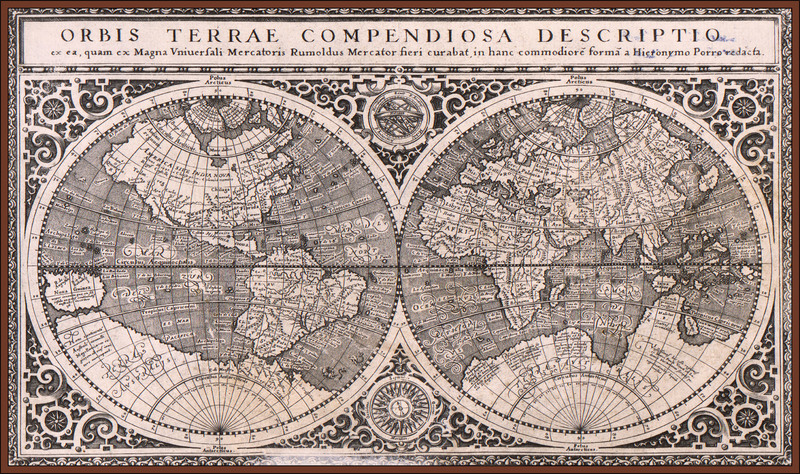

Gerhard Mercator (1512-1594), a close and influential friend of Ortelius, was a mathematician, globe and instrument maker, geographer, cartographer, and cosmographer. Mercator studied at the University of Leuven, under Gemma Frisius, an important mathematician and globe and instrument maker. It was through Frisius that Mercator became the most respected globe maker of his day. In the 1560’s Mercator began work on his famed atlas, which would shape the future of Dutch cartography. Mercator’s son Rumold (ca. 1545-1599) consolidated the maps and published the full edition of the Atlas sive Cosmographica Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (Atlas, or Cosmographic Meditations on the Fabric of the World and the Figure of the Fabrick'd) in 1595, one year after Gerhard’s death (Koeman, p.1323).

In 1604 Mercator’s grandson sold the copper plates to Cornelis Claesz. (1560-1609), a Dutch printer, publisher, and bookseller. Together with Jodocus Hondius Sr. (1563-1612), Claesz. published an updated version of the Atlas in 1606. It contained 37 new maps by various authors, including several engraved by Hondius himself. Even after Claesz’s death in 1609, Hondius continued to publish the Atlas until his own death in 1612. The 16 plates were passed to Hondius’s sons, Jodocus Jr. (1595-1629) and Henricus (1597-1651), and eventually Johannes Janssonius (1588-1664). They reused and reworked Mercator’s and Hondius Sr.’s copper plates and added their own maps to make the Atlas even more grand. By its last printing in 1675, the Atlas contained over one thousand maps.

Keunig, Johannes. “XVIth Century Cartography in the Netherlands: (Mainly in the Northern Provinces).” Imago Mundi, vol. 9, 1952, pp. 35-63.

Koeman, Cornelis, et al. “Commercial Cartography and Production in the Low Countries, 1500-ca. 1672.” From History of Cartography, v.3, pt.2.

Whitfield, Peter. The Image of the World: 20 Centuries of World Maps. San Francisco: Pomegranate Art Books, 1994.

Mr. Henry Vignaud and His Library