Ann Arbor and Race

With a liberal political climate, Ann Arbor has historically embraced diversity. Early settlers traded comfortably with Native Americans who came into town with deerskins, venison, berries and other items. City residents founded the Michigan Anti-Slavery Society in 1836. More than a dozen Ann Arbor homes were part of the Underground Railroad and offered safe haven to slaves making their way to freedom in Canada.

Ann Arbor Historical Notes, Population, and Enrollment

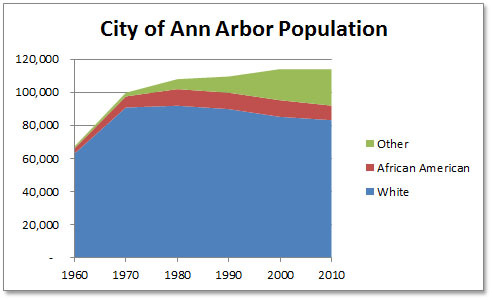

The census of 1870 listed 231 black community members, but this number soon grew. Due in part to building projects initiated by U-M president James Angell, many black laborers moved to Ann Arbor: between 1900 and 1910 the black population climbed to 515 residents, and continued to rise in the early 20th Century. By 1940, the black community in Ann Arbor was over 1,200 people, about 4% of the city’s population.

The city of Ann Arbor appointed their first black police officer in 1907. However, city government took much longer to diversify. Albert Wheeler, Ann Arbor's first black mayor, was not elected until 1975, more than 100 years after black residents began to settle in the area in large numbers.

Minority Enrollment All-Time High

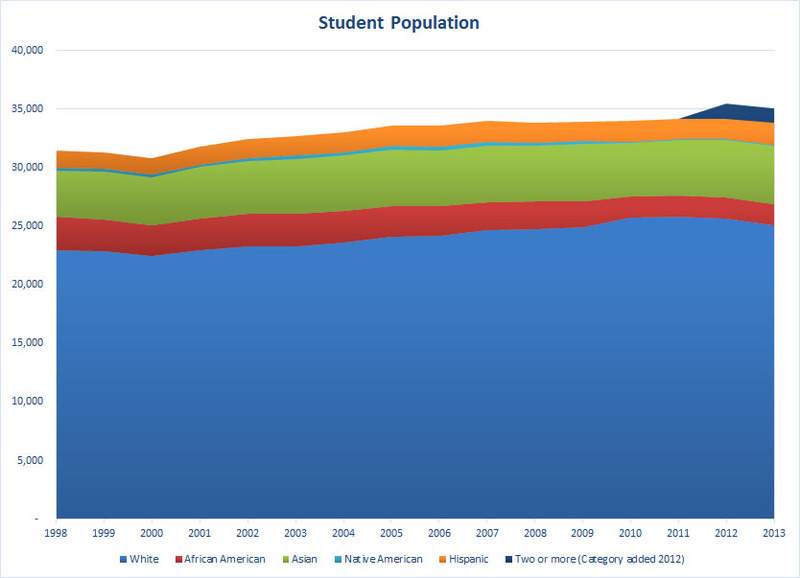

In 1992, enrollment of underrepresented racial groups reached 21.4% of the student body; with 7.8% of the student body African American. U-M President James Duderstadt had set a goal in 1988 to increase minority enrollment. After the 2006 ballot initiative forbidding consideration of race or gender in public education passed in Michigan, black enrollment began to decline considerably.

A Puzzling Problem

Reason for Race Prejudice in Ann Arbor

An unnamed writer offered a somewhat convoluted justification for the prevalence of racial prejudice in Ann Arbor in a 1912 Free Press article. The writer's theory was that the marriage of an American girl and a Chinese student that presented a “puzzling problem” caused by the matriculation of “Oriental students at the University of Michigan.” The writer mused that the presence of “foreign students” would make parents hesitate to send their daughters to U-M.

Lydia Belle Morton

Lydia Bell Morton’s family roots in Ann Arbor run deep. Her grandmother worked for the U-M men’s dean, and her mother played piano at the Music School. Morton says she only experienced direct racism once, when she and her husband were denied entry to a city union picnic even though Morton’s husband was a union member.

Morton wrote an editorial describing her frustration and received enormous community support. The man who turned them away from the picnic eventually lost his job. This renewed Morton’s belief in the uniqueness of the Ann Arbor community, where racial prejudice was not as common as it was in other places during this period.

In 2013, Morton was interviewed for the Living Oral History Project of the African American Cultural and Historical Museum of Washtenaw County.

Origins of U-M

Diversity in Student Life