Voting Rights: The Fight Against Voter Disenfranchisement

If the right to vote is what grants us our citizenship and political voice, then a democratic government that values the participation of the people should guarantee the vote for all people. Even in the face of questioning the real impact of the vote, there cannot even be the potential for democratic engagement without the vote. The ability of all citizens to vote has been unavailable since the founding of the United States. Only white, male, landowning citizens were given the right to vote in America’s founding documents. As women incrementally gained voting rights at the beginning of the twentieth century, Black women remained disenfranchised.

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many states enacted laws meant to hinder Black citizens’ access to economic and political agency. Among these were barriers to the right to vote. Requirements stipulating that voters own property, pay poll taxes, and pass literacy exams in order to cast a ballot, for instance, created major obstacles for African American communities. The Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 60s represented a major effort to remedy the voter disenfranchisement of African Americans. In 2013, the Supreme Court case Shelby County v. Holder struck down a crucial part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which required certain state and local governments to clear changes in election laws with the United States Attorney General or the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. This Supreme Court decision made it easier for states to enact discriminatory voting laws once again.

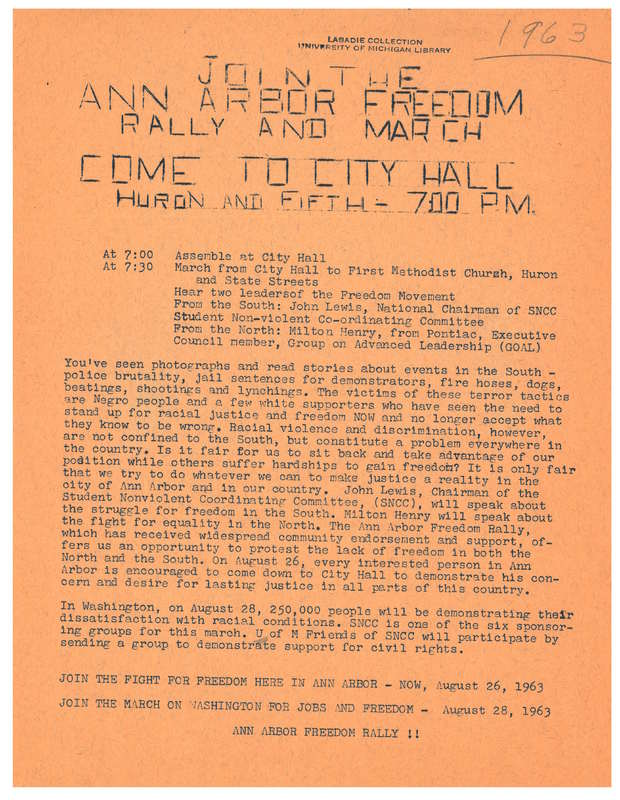

In the summer of 1963, Ann Arbor and many other cities were getting fired up in their local communities for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was to take place on August 28 in Washington, DC.

The flyer above was distributed locally to announce a rally in Ann Arbor on August 26. The headline states "Join the Ann Arbor Freedom Rally and March - Come to City Hall - Huron and Fifth - 7:00PM." Black residents in Ann Arbor were experiencing discrimination in housing and access to services. John Lewis was the main speaker at this rally. He was on a nationwide tour to raise awareness about the March on Washington and to gain support for the Civil Rights Movement.

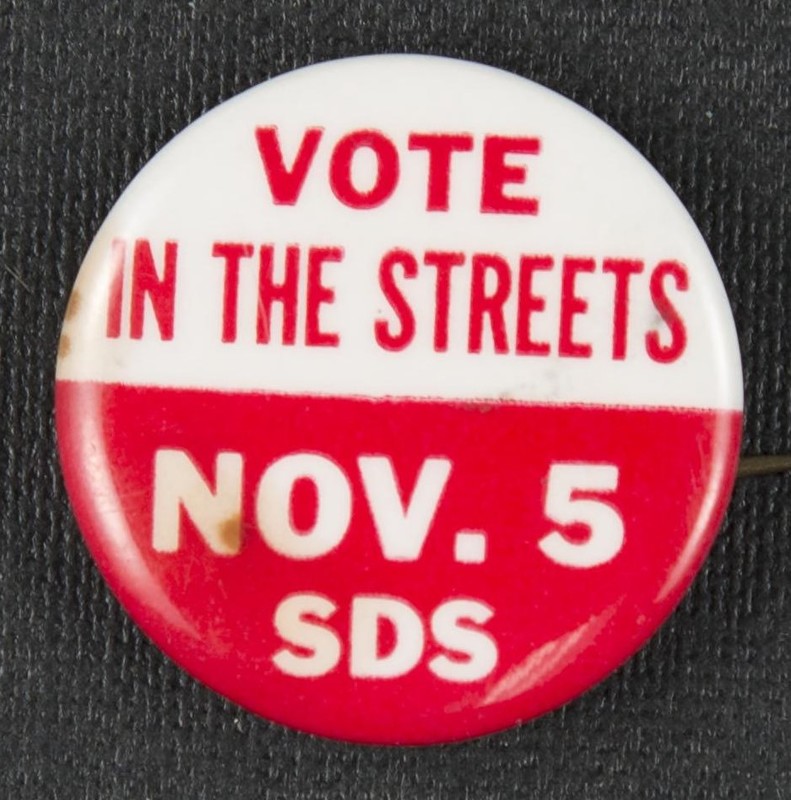

Student groups were actively involved in the fight for civil and voting rights. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had an active chapter in Ann Arbor in the early 1960s. Some University of Michigan students were involved. Out of this group came Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which was formed in response to the civil rights struggles in the North and the South.

This red and white pin from 1969, pictured above, reads “Vote in the Streets, November 5, SDS.” SDS is the acronym for the Students for a Democratic Society. The activist organization was strongly invested in the idea of “participatory democracy” and decentralized leadership, with the aim of promoting civil, political, and voting rights for all people.

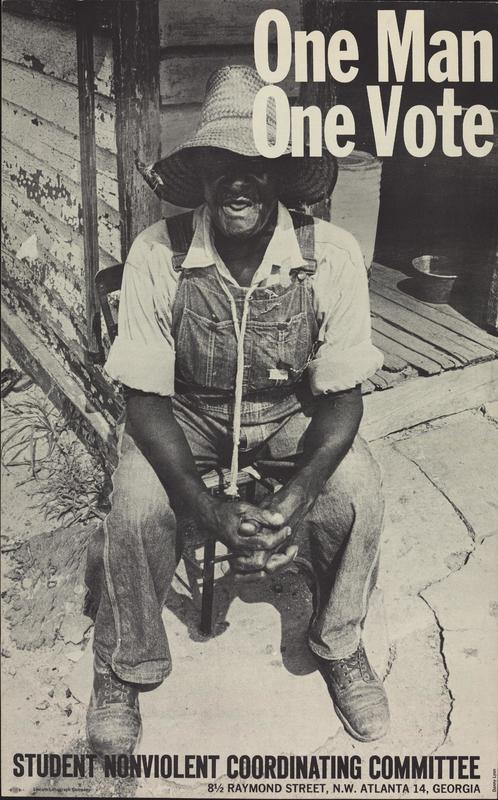

The poster above features an image of a Black man in work overalls, work boots, and a straw hat sitting on a chair near what looks to be his front porch made of worn wood and cracked cement. The main title text reads “One Man One Vote.” At the bottom it advertises for the “Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee” and lists the location of the committee at “8 ½ Raymond Street, N.W. Atlanta 14, Georgia.”

The pictured man represents ordinary people, such as poor, rural, African American farmers located in the Deep South that SNCC worked to help empower through their organizing efforts. In 1962 the SNCC began conducting voter education and registration drives in Mississippi using the slogan, “One Man, One Vote.” The slogan adorned buttons, banners, and posters.

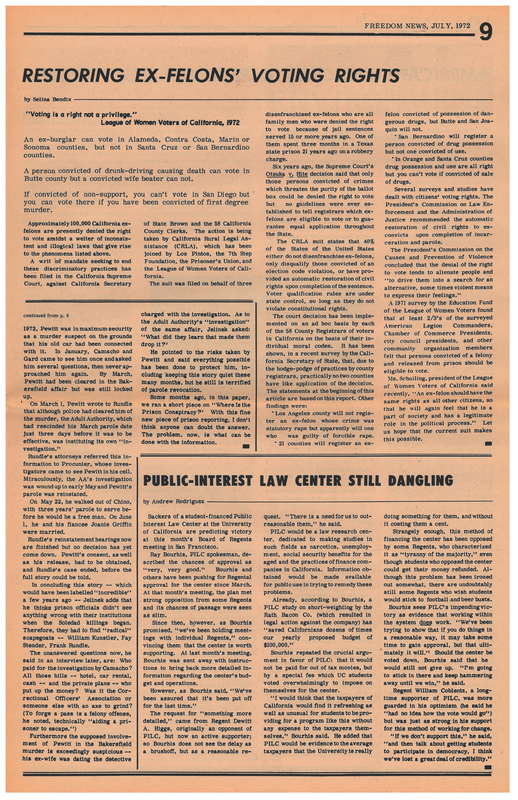

Incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people have also been targets of voter disenfranchisement. Most states disallow voting for felons actively incarcerated. But more than 30 states extend that disenfranchisement well beyond time served. Some 20 million Americans have felony convictions. When far, far more Black and brown Americans than white ones are convicted of felonies, this form of disenfranchisement secures meaningful advantages for the dominant political body (white, affluent, patriarchal).

The article above in the July 1972 issue of Freedom News, a local alternative community newspaper from Richmond, California, describes a lawsuit filed by the California Rural Legal Assistance group in 1972 on behalf of three disenfranchised ex-felons. It explains how voting rights for ex-convicts are differentially applied on the local level, based on varying interpretations of the Supreme Court's Otsuka v. Hite decision which limited denial of voting rights only to those whose crimes would "threaten the purity of the ballot box." Supporting the right to vote, evidence is provided from the President's Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence which found that denying voting rights may lead to alienation and negative, sometimes violent, expressions of emotion. The article closes with a quote from the president of the League of Women Voters of California who said that "An ex-felon should have the same rights as all other citizens, so that he will again feel that he is a part of society and has a legitimate role in the political process."

The long struggle to obtain voting rights for Black and other Americans of Color may, as part of the larger Civil Rights Movement, be emblematic of concerted efforts to deny or suppress the vote among a certain population. But it is by no means the only instance of such efforts, nor, indeed, is that struggle ended.

It was only on August 18, 1920, after a campaign lasting nearly 100 years, that the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment granted white women suffrage. It marked the single largest expansion of voting rights in the nation’s history and meant that political decision making could no longer solely reflect the priorities of white males.

This white pin shown above reads “I am woman, Watch me vote,” referencing the popular 1972 song by Helen Reddy “I am woman.”

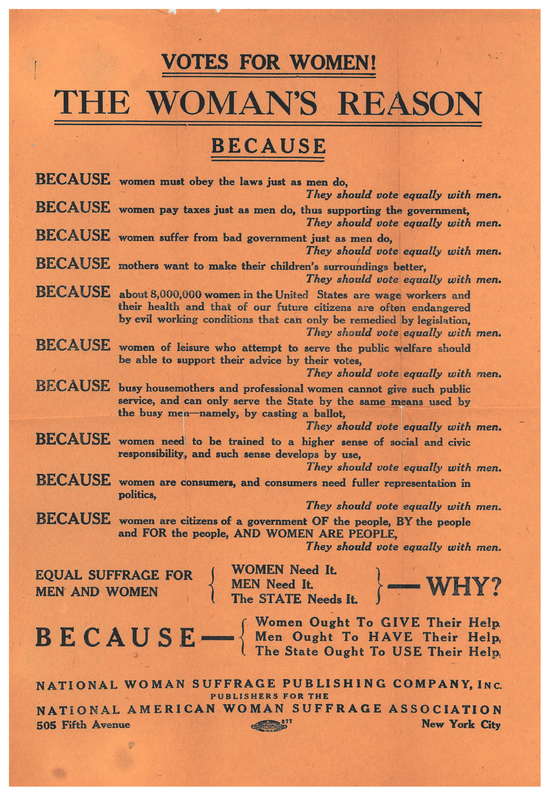

The above broadside was created in 1912 by the National American Woman Suffrage Association. It states 10 reasons why women should have the same voting rights as men. In making its case, the flyer alludes to a famous statement from Abraham Lincoln's second inaugural address when it reads, "Because women are citizens of a government of the people, by the people and for the people. And women are people."

Legal battles continue to affect the rights of voters in many states, which have changed rapidly before and since the 2020 election. Another current front for voter suppression is the debate over mail-in ballots, with some fighting to limit access to mail in ballots on the basis of unsupported accusations of voter fraud. Voting rights groups seek to expand access to mail-in ballots in order to make it easier and more convenient for people to vote.

Independent Journalism: Making Dissident Voices Heard

Anarchism & Anti-Voting