Altman Sound & Music

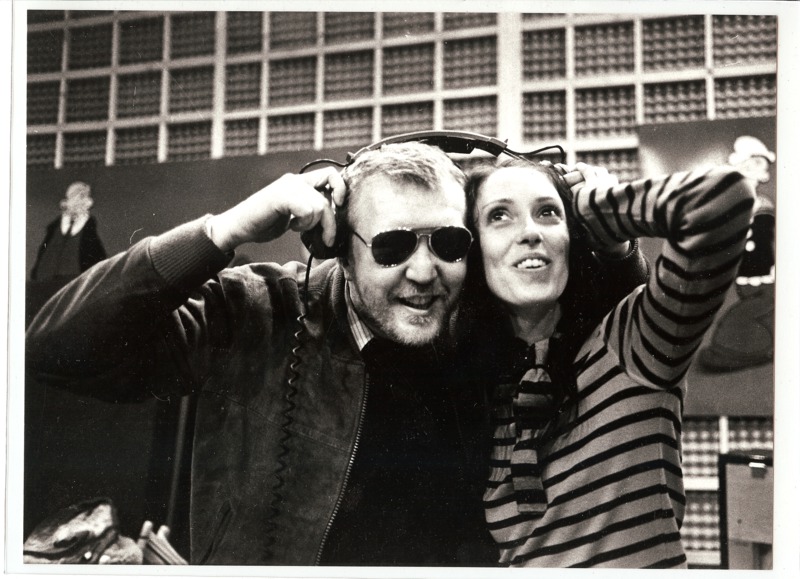

Robert Altman had a passion for music, though he said he could not read a note on the page. This passion shows up again and again in his work, going all the way back to the lyrics he penned in the 1940s, to filming music-rich films such as Nashville and Popeye, recreating the Kansas City jazz environment of his youth in Kansas City and Jazz ’34, and collaborating in staging operas with Bill Bolcom. And if music was a personal passion, Altman’s use of sound in his films is a professional trademark that is among the most distinctive of his work.

The Altman Sound

The spaceshot movie Countdown (1968) featured the overlapping dialogue that became an Altman trademark – and is said to have gotten him fired from the project and banned from the studio lot! This technique presented challenges to the technical crew as well as to the actors. Altman’s notable sound mixers included James Webb and Robert Gravenor, who are credited with creating “that whole process of simultaneous multitracks for production sound.” It has been suggested that the reason there were 24 characters in Altman’s Nashville was because of the music industry’s common use of 24-track recording. Each character was recorded separately and then brought together physically and metaphorically via the sound mixing board. Among the realia included in the Altman Archive is a Yamaha 802 sound mixing board.

The quintessential and recognizable Altman trait of using overlapping sound and dialogue has been pointed to as a symbol of the messiness of real life, of making characters behave more as their real-life counterparts do. It is so much a part of how he is known as a director that Lily Tomlin and Meryl Streep used it brilliantly in presenting him with an Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 2006.

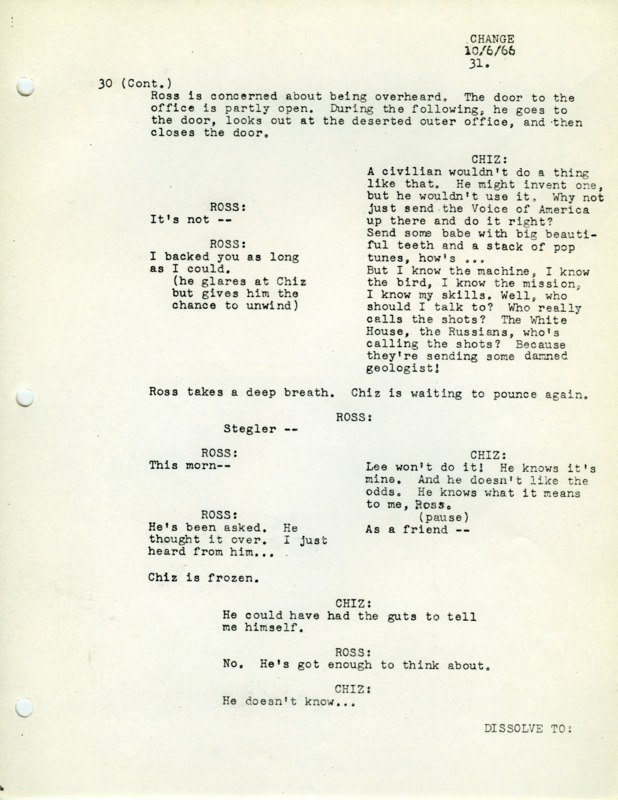

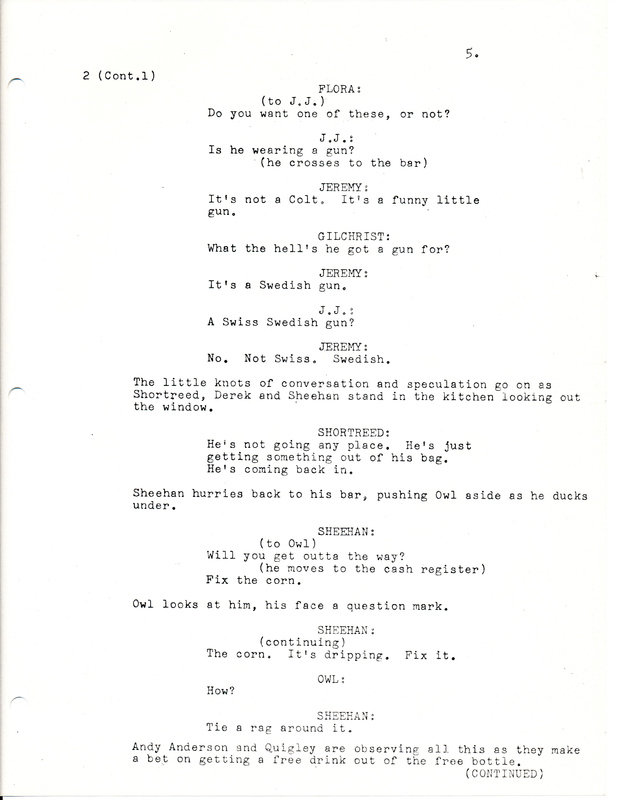

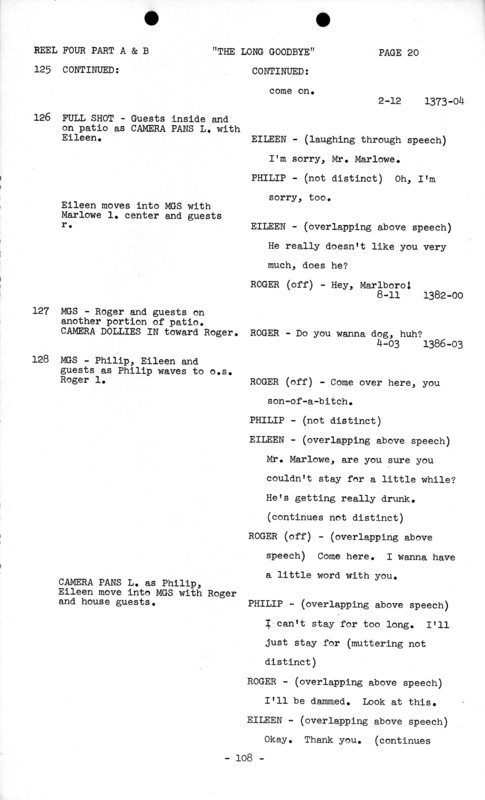

Even in various screenplays with different writers, by the final drafts they seemed to indicate in some way Altman’s desire to use overlapping dialogue. Not surprisingly, the Altman Archive, contains documents that reflect how this signature overlapping was achieved, being carefully written down. There are a number of subtle marks within the scripts:

- In Countdown (1968) the writer puts the dialogue of two characters side by side

- In McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971) parenthetical cues begin to appear, but are very sparse and subtle

Songs & Rights

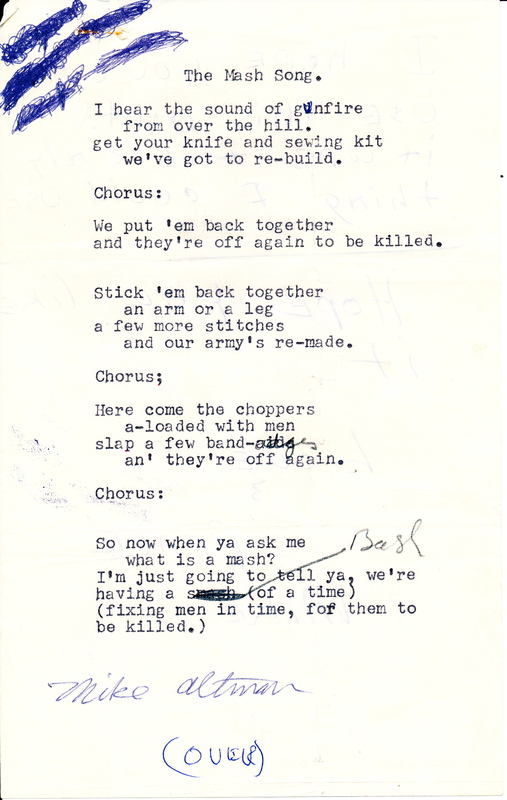

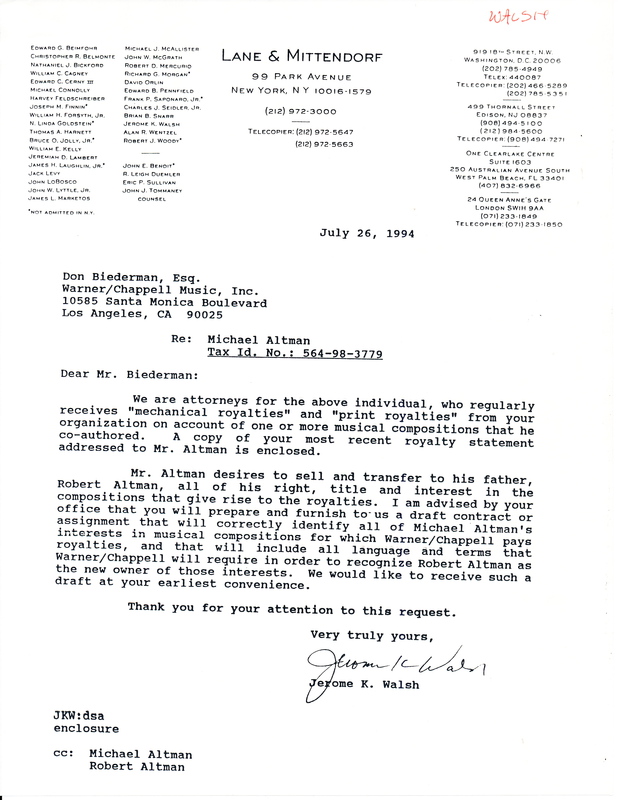

Michael Altman, son of Robert Altman, wrote the lyrics to the theme from M*A*S*H when he was only 14 years of age in 1969. An original draft for the lyrics signed by him is in the Altman Archive. The song’s music was written by veteran songwriter Johnny Mandel. In an interview in the 1980s, the director said that his son had made more than a million dollars in royalties for the song, while his fee for directing the hit film had been $70,000. Given the popularity of the television show M*A*S*H which used this song as their theme, the large and continuing royalties payments are not surprising. In the American Film Institute’s “100 Years … 100 Songs” it is ranked #66. The archive has legal documents from 1994 showing Altman buying the rights from his son, after months of correspondence and draft agreements.

M*A*S*H Song (Suicide is Painless)

Through early morning fog I see

Visions of the things to be

The pains that are withheld for me

I realize and I can see…

[chorus]

That suicide is painless,

It brings on many changes,

And I can take or leave it if I please.

Working with Composers

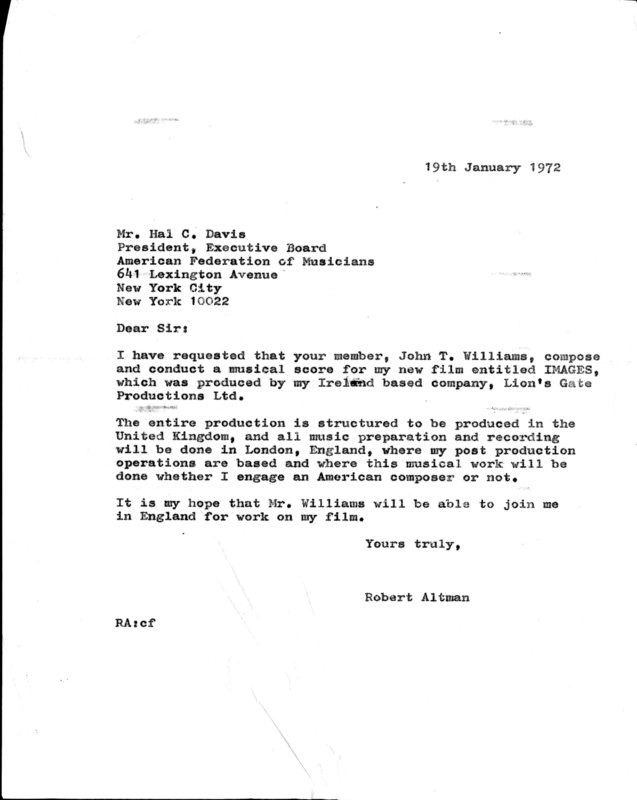

John Williams, the prolific American film composer who wrote memorable scores for films like Star Wars and Jaws, worked with Altman on Images (1972)and The Long Goodbye (1973). His score for Images, matching the film’s psychological tone, was nominated for an Oscar. The Robert Altman Archive contains items that show many behind-the-scenes agreements and working documents that were part of the complex world of creating films.

Popeye (1980), Altman's first and only attempt at a musical, was riddled with drama throughout its production. Harry Nilsson, the composer who wrote the featured songs, didn't expect Altman's changeability with the score and left the island of Malta halfway through filming. Altman trusted Nilsson to finish the production and claimed to get on with him terrifically despite the disagreement. In the end the dispute was settled, and all of Nilsson's songs are featured in the final film.

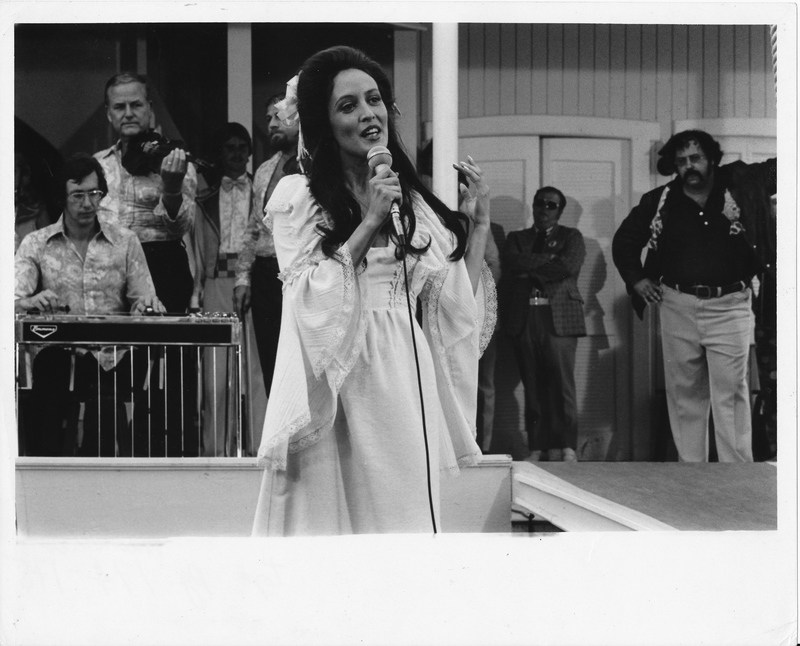

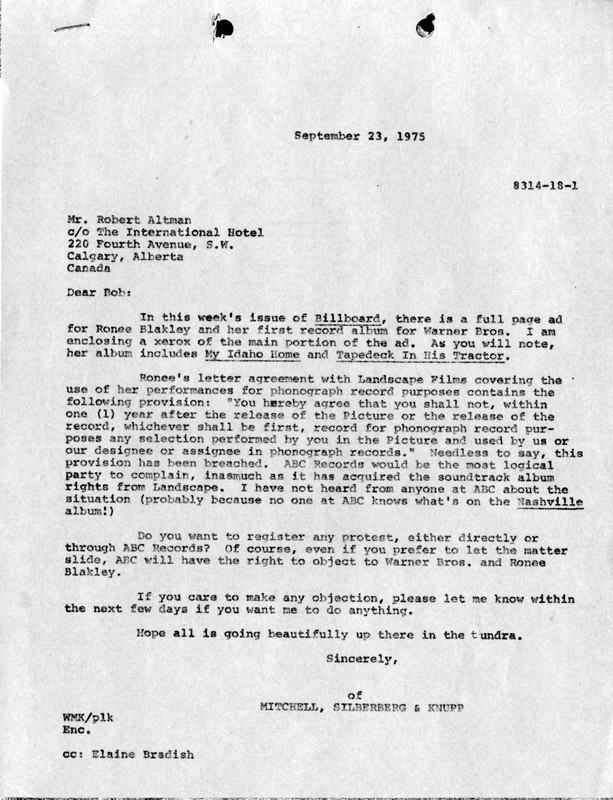

After Ronee Blakley starred as Altman's fragile country singer Barbara Jean in Nashville, she released an album within that same year featuring several songs she wrote, composed, and performed from the film. This violated the contract between Blakely and Altman, which spiraled into a series of lawsuits that extended 1975 to 2005.

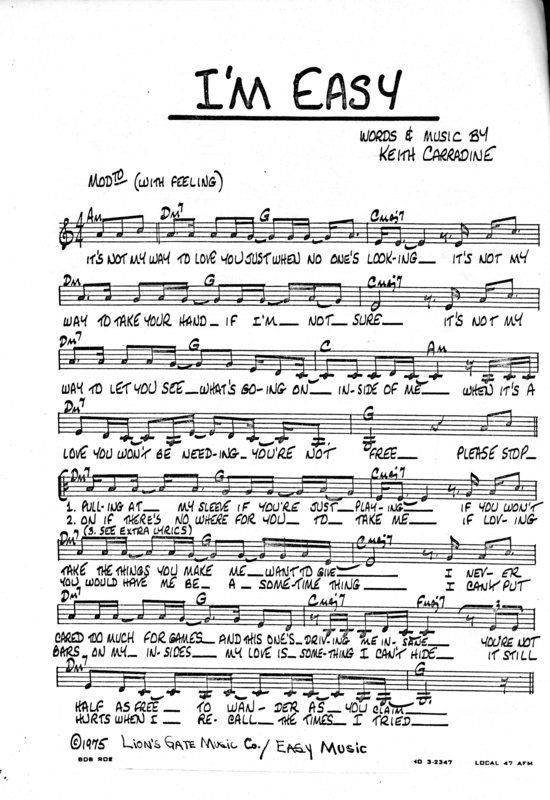

Nashville

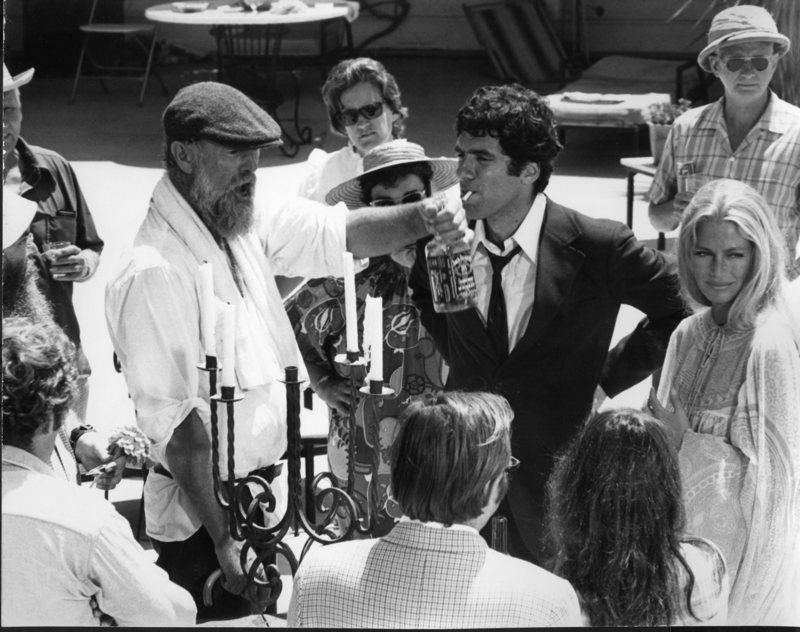

Nashville (1975) is arguably the most highly acclaimed Altman film, in large part due to the fantastic sound throughout it. This film is a perfect example of a large ensemble cast, which was an aspect of film Altman became very well known for. In its time Nashville was widely labeled as the best portrayal of the United States of America in any film to date. Altman’s masterful use of music as well as overlapping dialogue permeates the film and creates an incredible auditory experience from start to finish.

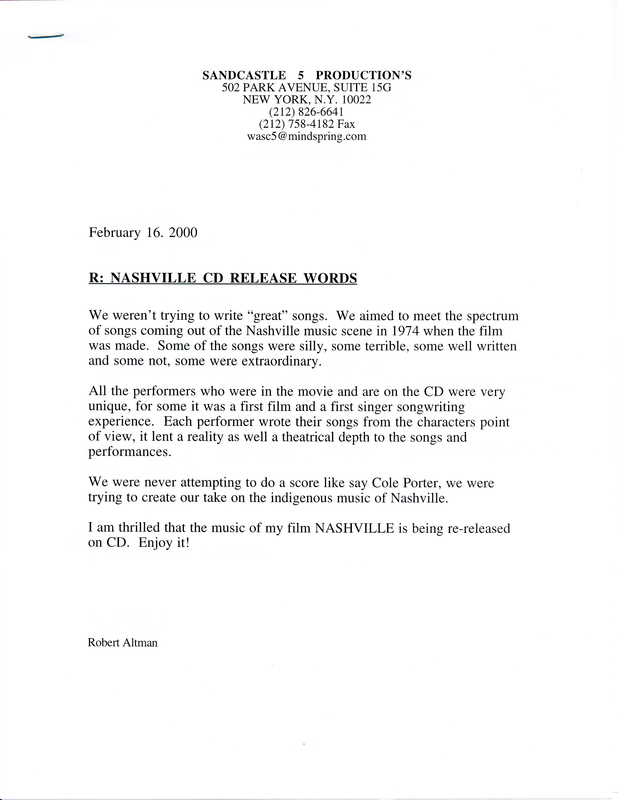

Altman has always been known for making an accurate portrayal of the era in which his films take place. In this essay for a new CD of Nashville’s music he speaks of this intention to be authentic. Altman’s deliberate use of songs of all form and quality display the range of the music industry in Nashville in 1974. By having the songs written by the performer whose point of view they are portraying, it helps increase the depth and believability of character, which is consistently a strong point in Altman films.

Altman & Genres

About this Exhibit