Printing in Venice & Benedetto Bordon

Printing with movable type was originally introduced in Italy by the German printers Konrad Sweynheym and Arnold Pannartz, who issued books at Subiaco and Rome from 1465 onwards. In Venice, another German, Johann Speyer, printed his first book in 1469. Venice soon attracted many other printers from Italy and the rest of Europe, such as Aldus Manutius, Nicholas Jenson, and Erhard Ratdolt. Venice was indeed an excellent choice for two reasons. First, the city had been the main commercial city of Italy for many centuries, being very well connected by sea and land routes with western and northern Europe. Second, the intellectual atmosphere of Venice in the second half of the fifteenth-century was ideal for the publication of Greek and Latin authors. Venetian humanists were interested in rediscovering all aspects of antiquity, including science, philosophy, and literature. Many of these intellectuals gravited around the prestigious teacher and scholar, Ermolao Barbaro, who in turn had an extraordinary library of Greek and Latin manuscripts. And following the capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, Venice overwhelmingly welcomed a dispora of Greek scholars, many of whom actively collaborated in printing entrerprises as scribes, type designers, and editors.

There is evidence that Benedetto Bordon accepted commissions to decorate printed books, most of them coming from Venetian presses. We know of two individual copies of books printed in Venice by Nicholas Jenson in 1477 (Justinianus, Digestum novum) and 1479 (Gregory XII, Decretales) that include the following inscriptions in their respective hand-illuminated frontispieces: BENEDIT. PATAV. OPVS and BE. PAT. Many scholars rightly argue that this Benedetto of Padua should be identified with our Benedetto Bordon. Furthermore, in a letter dated January 13, 1515 by the nobleman and scholar Andrea Navagero to Giambattista Ramusio, Navagero mentions that "Benetto" has done the miniature in his copy of Vergil. Though this particular copy is no longer extant, it is very plausible that Navagero was referring to the Aldine edition of Vergil of 1514, in which Navagero's assistance is acknowledged as editor in the preface.

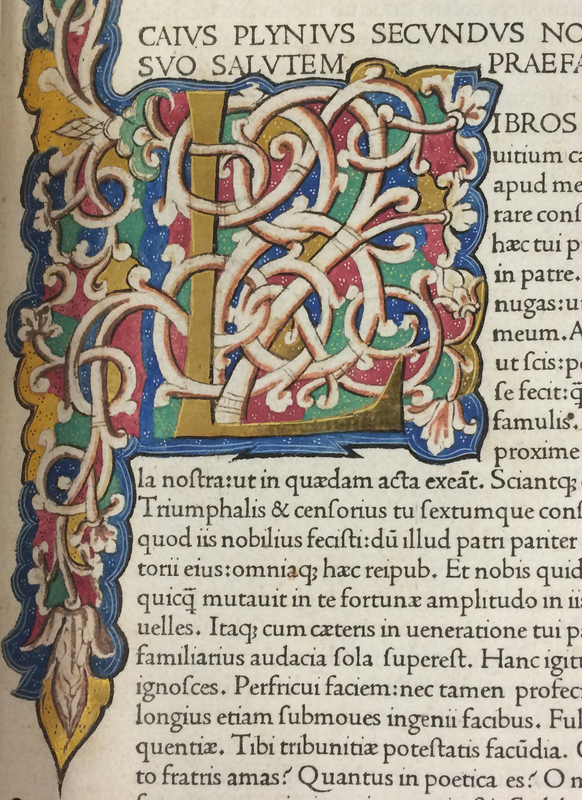

In brief, this type of old-fashioned manuscript illumination applied to the product of the new technology of printing was fairly common until the end of the fifteenth-century. Wealthy owners would personalize their recently purchased books by commisioning special bindings and an illumination of the kind executed by artists like Bordon. Above we have included an excellent example of this practice from our copy of Pliny's Historia Naturalis (Venice: Nicholas Jenson, 1472). More importantly, and as we will discuss in the next pages of this exhibit, in Venice Benedetto launched two major printing projects as a woodcut designer: Pliny's Natural History (1513) and a description of all known islands, the libro di Benedetto Bordone (1528). Moreover, it is very likely that Bordon was the woodcut designer of the first edition of Francesco Colonna's Hypnerotomachia Poliphilii (Venice, Aldus Manutius, 1499).

Lucianus Samosatensis (1494)

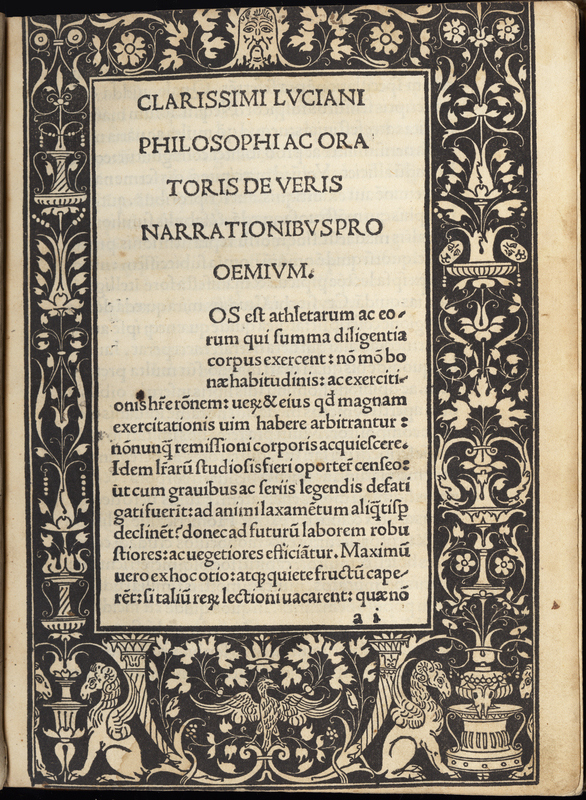

Benedetto Bordon was fully responsible for the design of this edition of Latin translations from the dialogues of Lucian of Samosata (c. 120-c. 180), printed by Simon Bevilaqua in Venice in 1494. Being aware of what readers expected to see when an ancient author was published, he chose a small portable octavo, a format that, in a slightly smaller and elongated size, Aldus Manutius would use to print classical authors from 1501 onwards. In this image of the prologue, folio 1, one can appreciate the extraordinary clarity of the Roman typeface, exquisitely surrounded by a black-ground woodcut border with elegant ancient motifs. This magnificent border is actually the earliest extant evidence of Bordon's work as a designer of woodcuts.

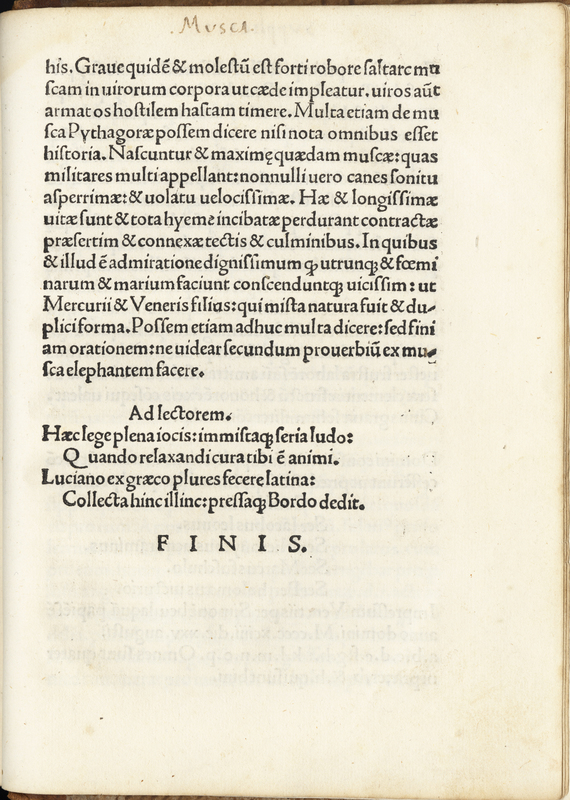

In the form of a colophon, Bordon added this charming Latin poem whereby he encourages readers to engage with the playful spirit of the dialogues with their mixture of jokes and seriousness, for they are the perfect recipe when the concern is to relax the soul (quando relaxandi cura tibi est animi). Bordon also states that several people have translated Lucian from the Greek into Latin, having gathered these translations from here and there (collecta hinc illinc) to include them in this volume.

Author of some 80 short pieces, mostly in dialogue form and on a wide range of topics, Lucian was rediscovered in humanistic circles through a series of Latin translations undertaken from the end of the fourteenth century onwards. Eventually, Greek refugees working as teachers in Italy realized that the language of Lucian was not only easy to learn for beginners but fairly suitable to be translated into Latin without sacrificing the tone of the original.

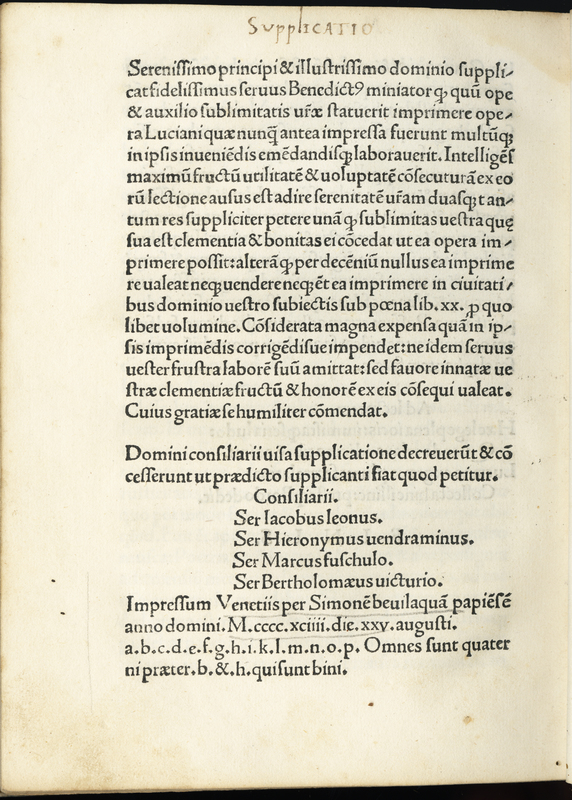

The founder of printing in Venice, Johann Speyer, had the brilliant idea to secure for his books a privilege from the Senate of Venice so that everybody else was prohibited to print in the Venetian dominions for five years. Within a few months Speyer died and this privilege was cancelled. The Venetian authorities soon realized that granting the monopoly of printing was not a good idea so this privilege was restricted to particular books. Here in the last page of his edition of Lucian, Bordon printed a copy of the privilege that he had requested to the Senate of Venice. Essentially, he asked, and was of course granted, that nobody else be allowed to print or sell this book for ten years in Venice and the cities ruled by the Doge, the highest civil authority. But Bordon might have been carried away in his desire to convince the authorities about the excellence of this edition, erroneously stating that the works of Lucian had never been printed before (quae nunquam antea impressa fuerunt). Actually, the first printed edition (editio princeps) of the Latin translations of two dialogues by Lucian had been published by Georgius Lauer in Rome around 1470-1472.

Pliny's Historia Naturalis (1513)

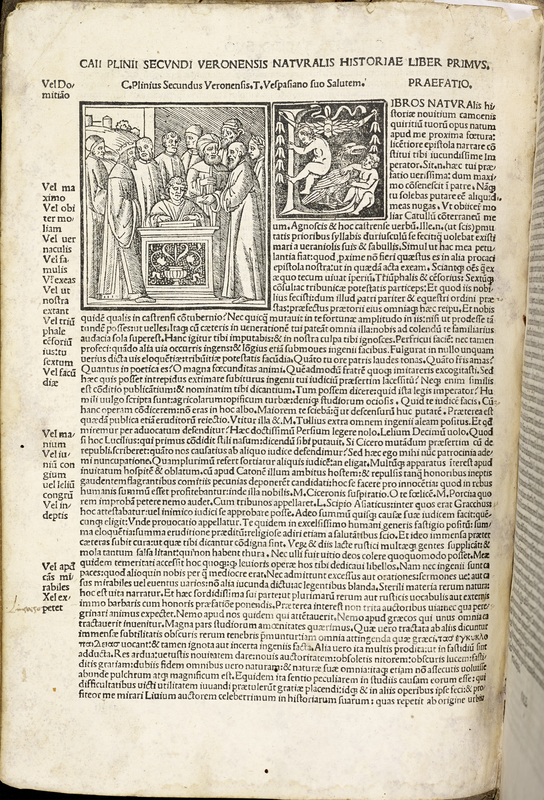

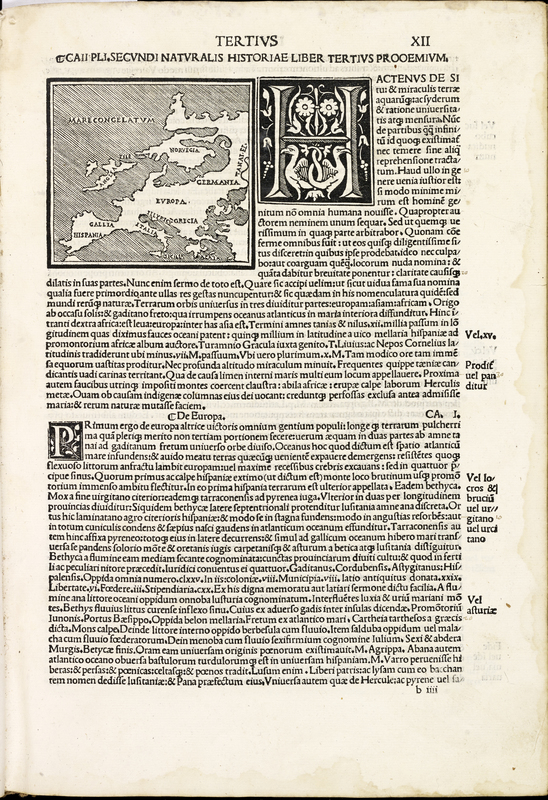

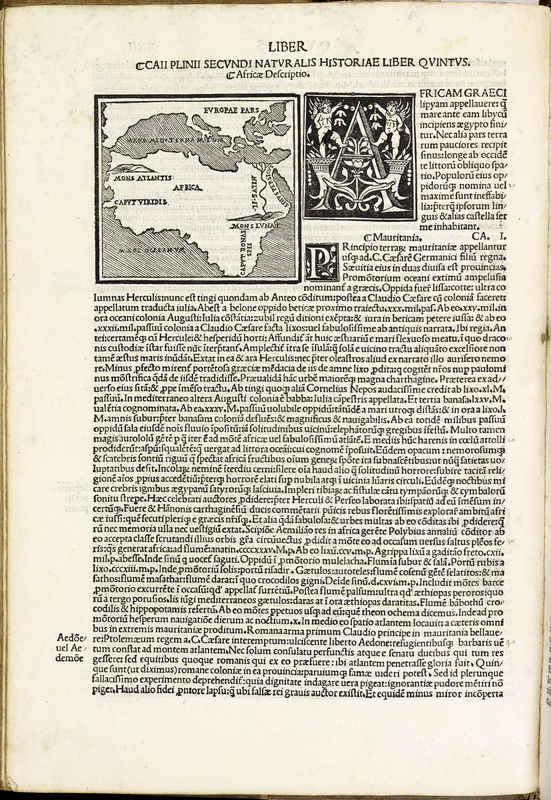

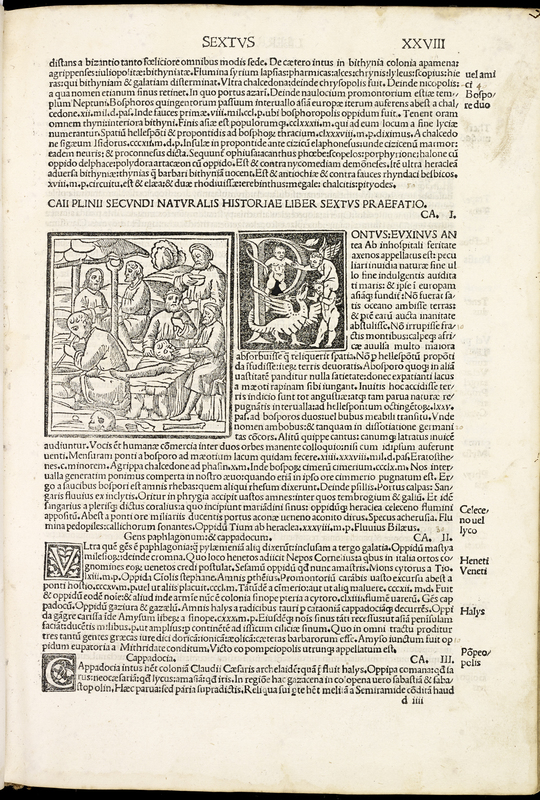

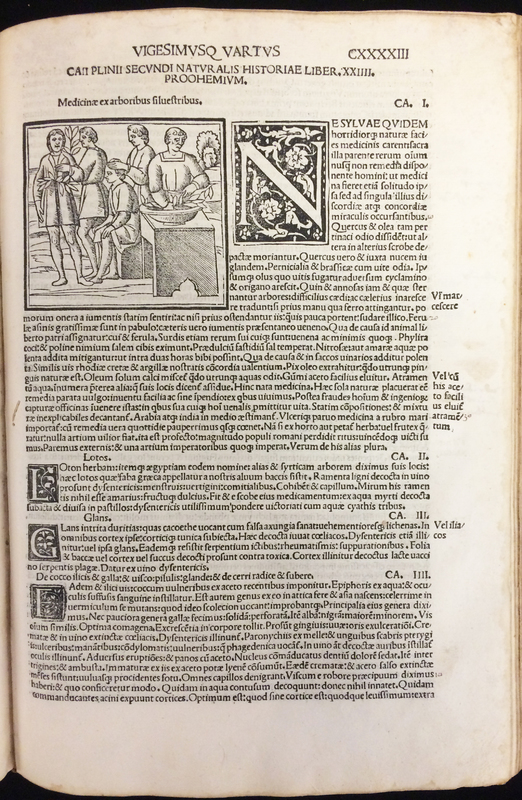

Here is a selection of images from our copy of the first illustrated edition of Pliny the Elder's Natural History (Historia naturalis). Printed by Melchior Sessa and edited by Alessandro Benedetto of Verona, it is very likely that the woodcuts of this edition were designed by Benedetto Bordon. Each of the 37 books of this work begins with a woodcut and an ornamented woodcut intial. For example, observe the layout of the Praefatio. Pliny is sitting at his desk; to the left we see the crowned figure of the emperor Titus, to whom the Natural History was dedicated; around him are other figures, plausibly the authorities that Pliny acknowledges as his sources. This composition, argues scholar Lilian Amstrong, reminds us of Bordon's miniatures in a vellum copy of the 1494 edition of Lucian.

Libro di Benedetto Bordone (1528)

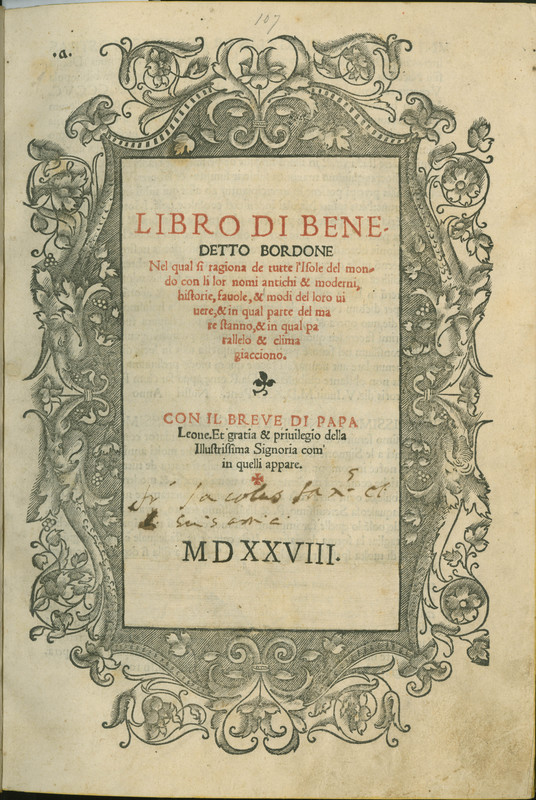

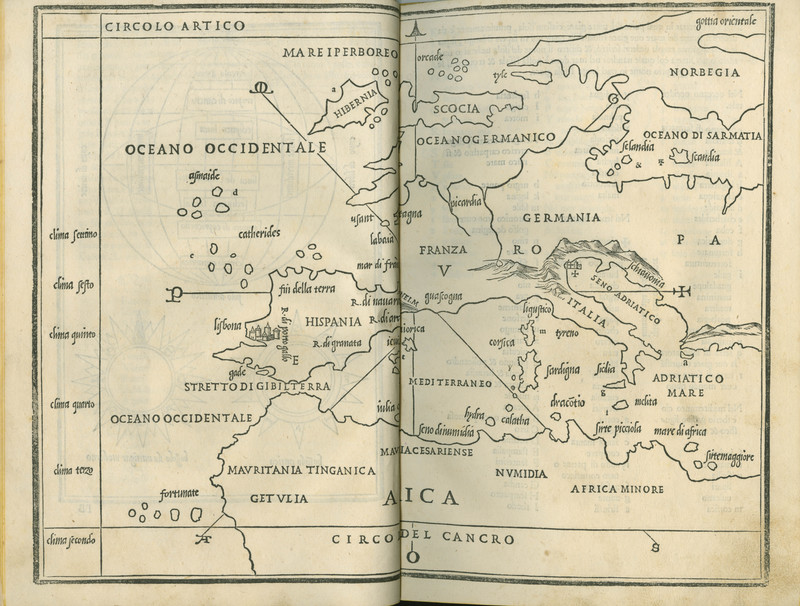

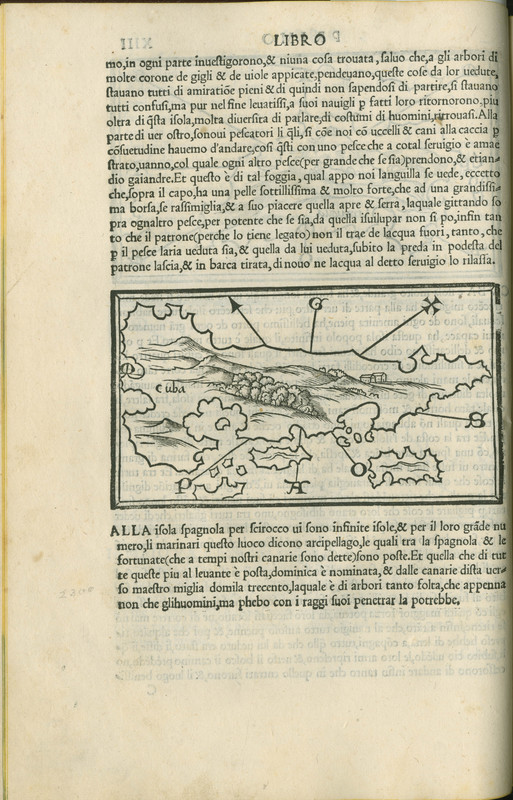

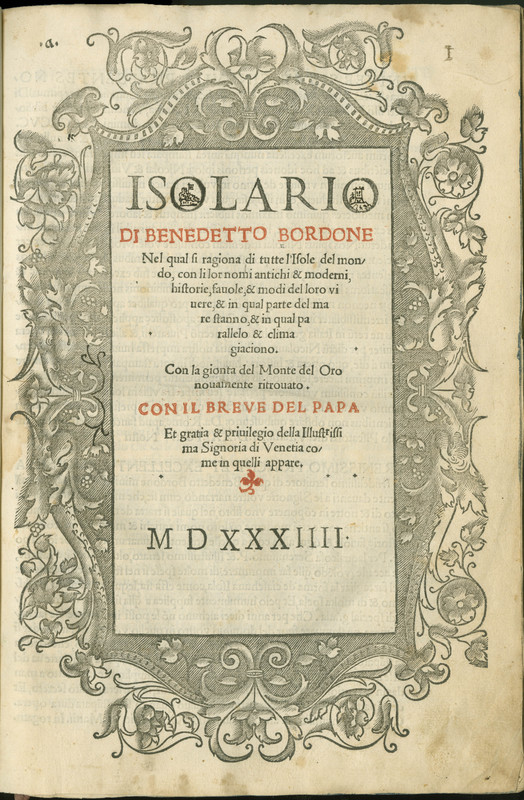

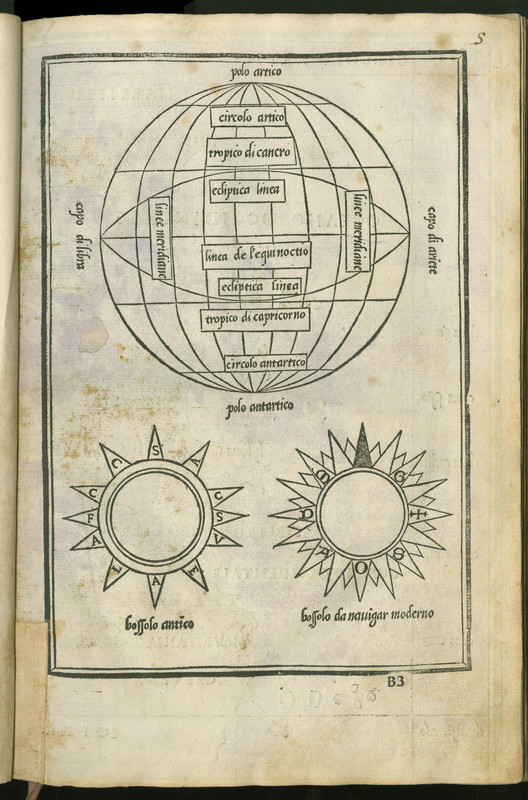

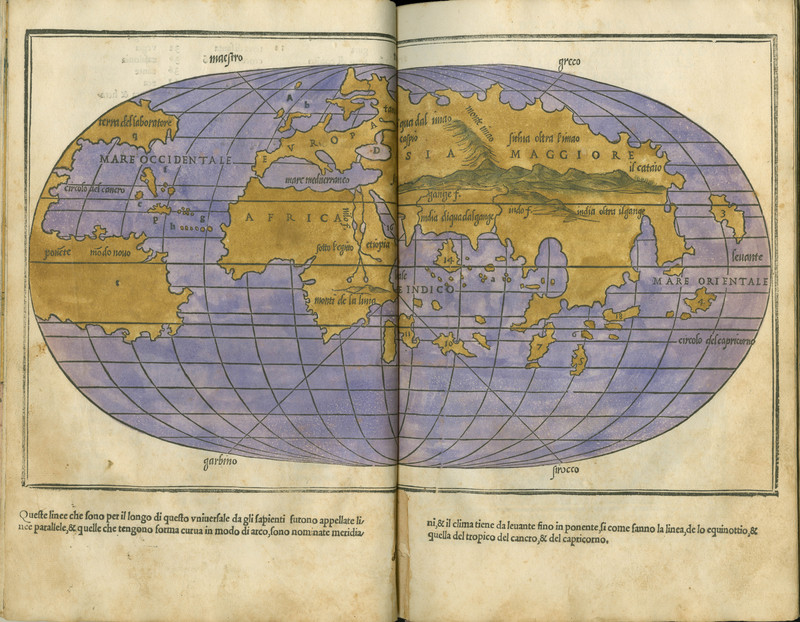

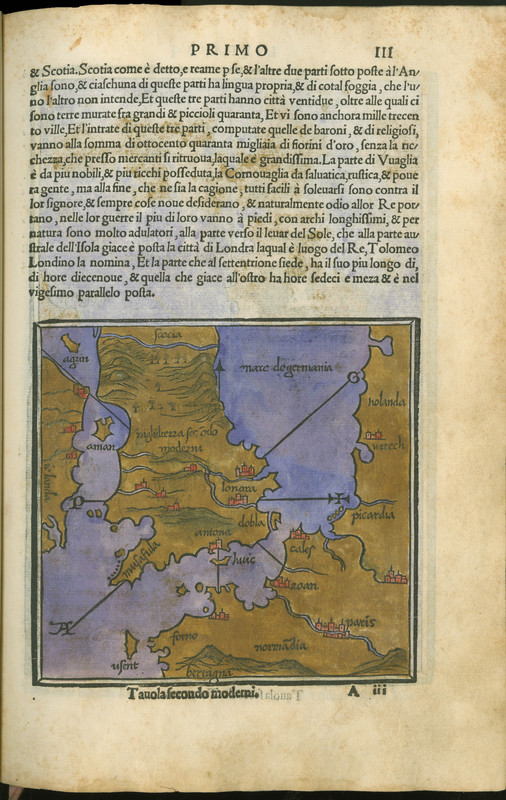

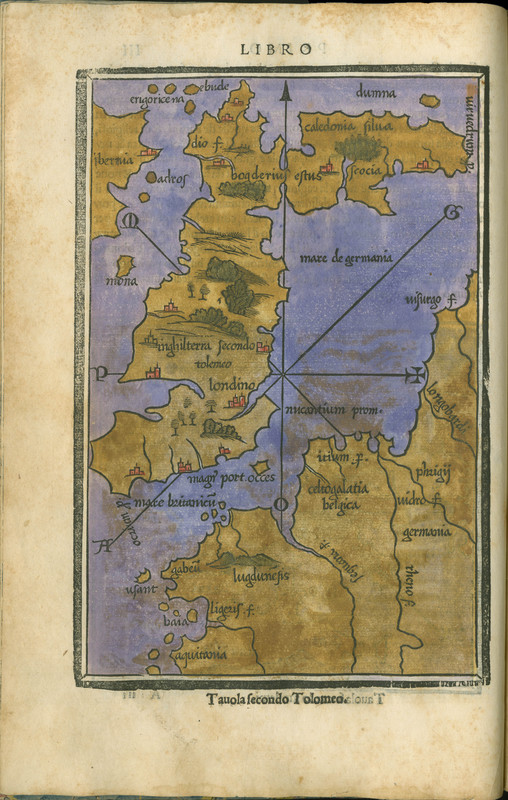

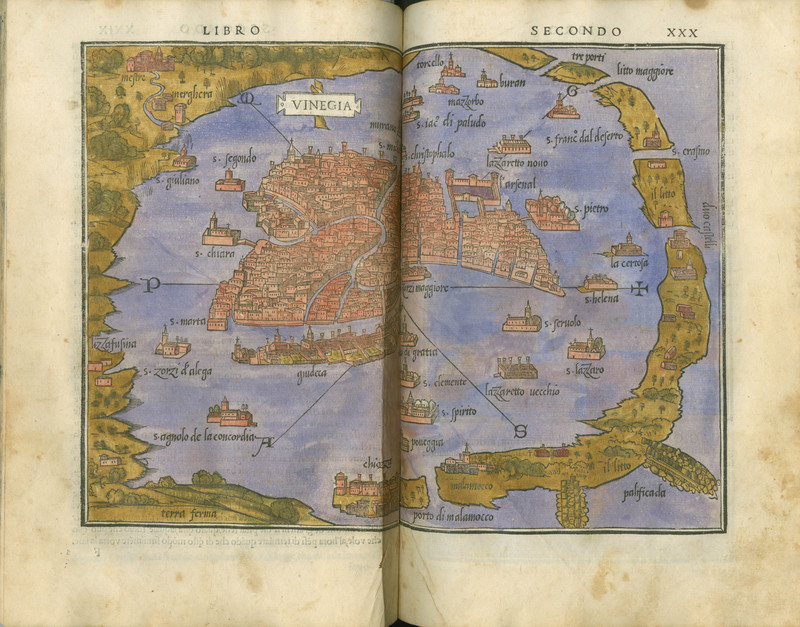

The Libro di Benedetto Bordone is an eighty-folio book that describes all the islands of the world (nel quale si ragiona de tutte l'isole del mondo). Designed and edited by Bordon, Niccolò Zoppino printed it in Venice in 1528. The title page is framed by a woodcut border that originally appeared in the earliest illustrated edition of Vitruvius's De architectura (Venice: Johannes Tacuinus, 1511). The preliminary material includes woodcuts depicting a schematic sphere, three maps of Europe, the Aegean, and the world. Then, the rest of the book is a consistent sequence of text in Roman typeface and woodcuts of islands framed by pairs of lines.

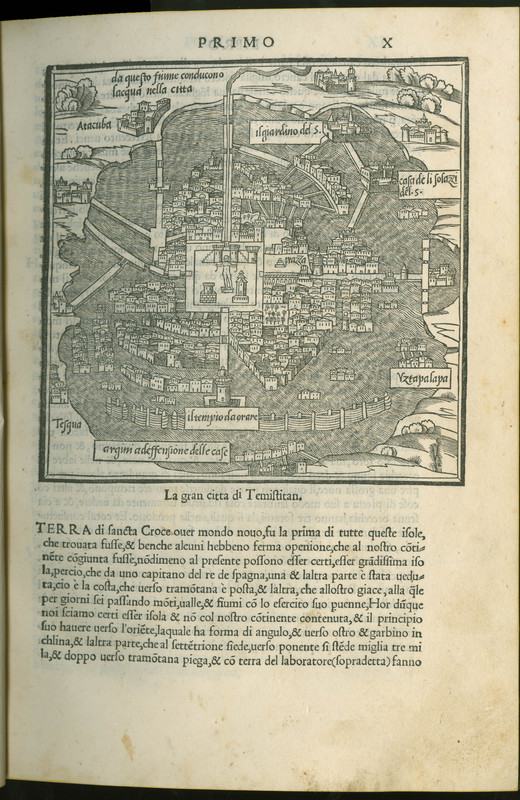

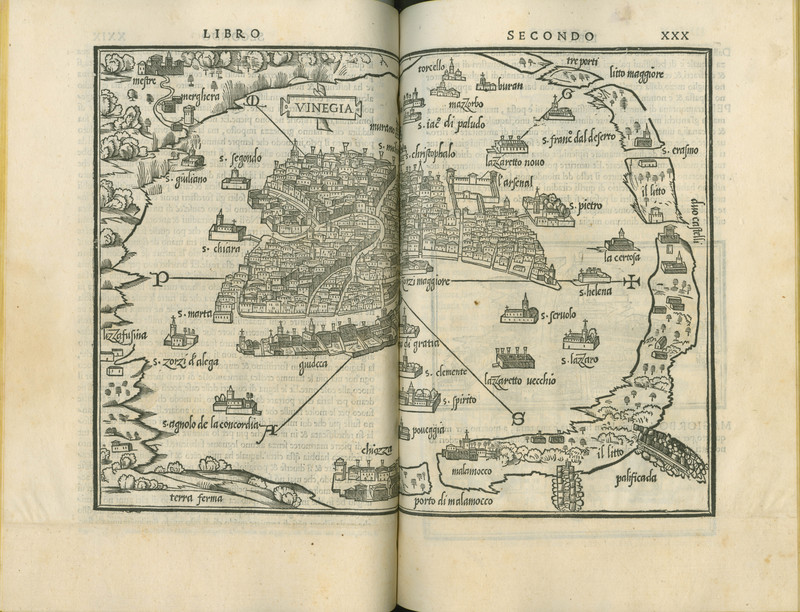

Specifically, the text is divided into three books. Book I includes 21 maps and descriptions of the islands in the Atlantic as well as a city plan of Tenochtitlan; Book II has 74 islands in the Mediterranean and bird's views of several Italian cities; and Book III contains 8 islands in the Indian Ocean and near East Asia. In general, the islands are described in simple lines, with occasional details such as mountains, trees, towers, and houses. The Libro is particularly fascinating for inserting the latest discoveries by the Spanish in the Americas. See, for instance the magnificent woodcut of the city of Mexico (Tenochtitlan).

Libro di Benedetto Bordone (1534)

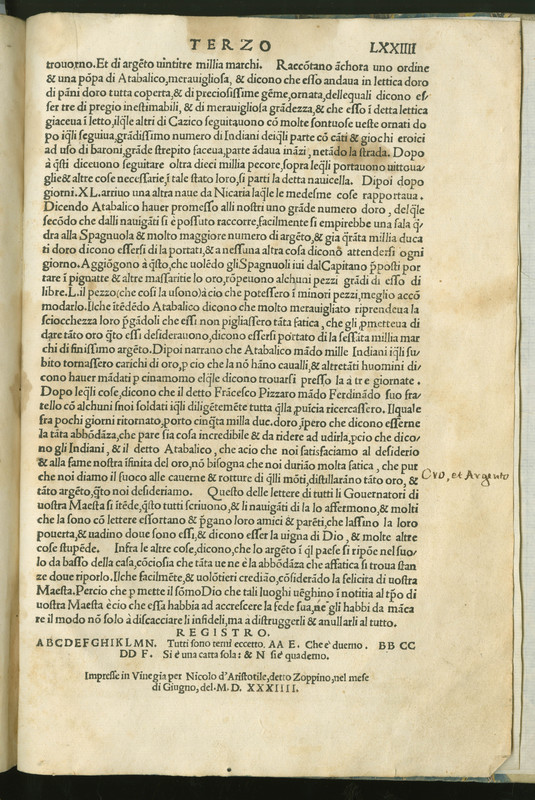

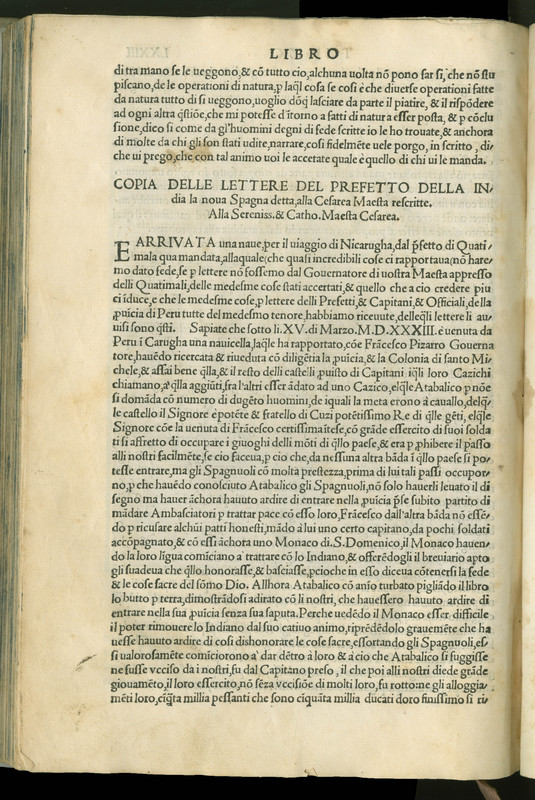

Here we are displaying a selection of images from the second edition of the Libro di Benedetto Bordone, published, like the first edition, by Niccolò Zoppino in Venice in 1534. The publisher reused the same woodcuts as the 1528 edition, but this particular copy has been hand-colored by a contemporary artist. Among the images, is a magnificent map of the world, greatly based on engravings of world maps by the miniaturist and cartographer Francesco Roselli (1447-c. 1513). However, Bordon introduced important modifications to reflect new geographical knowledge. North America (terra del laboratore) is joined to South America (mondo novo) by land, and the mare orientale reappears continuously on the right edge, emphasizing the separation of Asia from America. Moreover, at the end of the book is a copy of a letter addressed to the emperor Charles V by a unknown officer (prefetto della India la nova Spagna). It contains the account of Francisco Pizarro's conquest of Peru. In turns, it is a copy of a pamphlet published also in 1534. Possibly, it is a translation and summary of the Spanish original letter, of which no copy is extant.

About the Exhibit

This exhibit is the outcome of a truly interdiciplinary initiative that, by combining expertise in various areas such as music, art, and manuscript studies, has greatly contributed to our understanding of a richly decorated fifteenth-century antiphonary (Mich. Ms. 246).

If you have questions or comments about the exhibit, please, contact Pablo Alvarez (pabloalv@umich.edu).

For more information about the University of Michigan Special Collections Center, please visit our website.

Acknowledgments

My most sincere gratitude goes to the group of six extraordinary singers who enthusiastically undertook this project and performed beautifully with little rehearsal time: Adam Wills Begley, Noah Horn, Austin Stewart, Glenn Miller, Matthew Abernathy, and Dr. Stefano Mengozzi. The filming and editing was made by Zoë Crowley (Media Assistant II, Learning & Teaching Unit) and David Hytinen (Media Consultant, Learning & Teaching Unit).

The content of this exhibit greatly depends on the scholarly work of Dr. Lilian Armstrong. I sincerely hope that the selected bibliography dutifully reflects her work in reconstructing the content of the six antiphonaries and in identifying Benedetto Bordon as the author responsible for the illuminations in these magnificent manuscripts.

This online exhibit has been a truly collaborative project, which is attested in the following list of colleagues who generously helped at its different stages:

Karmen Beecroft, Collection Services Specialist, Special Collections Library

Lucia Campbell, Minister of Music at St. Thomas Apostle Catholic Church, Ann Arbor

Emiko Hastings, Curator of Books & Digital Projects Librarian, Clements Library

Nancy Moussa, Web Developer, Library Information Technology

Meghan Musolff, Special Projects Librarian, Library Information Technology

Randal Stegmeyer, Media Digital Photographer, Digital Library Production Service

Rights Statement

The University of Michigan Library has placed copies of these works online for educational and research purposes. These works are believed to be in the public domain in the United States; however, if you decide to use any of these works, you are responsible for making your own legal assessment and securing any necessary permission. If you have questions about this exhibit, please contact the Special Collections Research Center (special.collections@umich.edu). If you have concerns about the inclusion of an item in this exhibit, please contact ask-omeka@umich.edu.

Selected Bibliography

Angioli, Gabriela. "Codici rinascimentali della Chiesa di S. Francesco a Lucignano in Valdichiana." Miniatura 5-6 (1993-1996): 27-40.

Armstrong, Lilian. "Benedetto Bordon, 'Miniator', and Cartography in Early Sixteenth-Century Europe." Imago Mundi 48 (1996): 65-92.

________. "Benedetto Bordon, Aldus Manutius and LucAntonio Giunta. Old Links and New." In Aldus Manutius and Renaissance Culture. Essays in Memory of Franklin D. Murphy, ed. David S. Zeidberg, 161-183.

________. "Benedetto Bordon and the Illumination of Venetian Choirbooks around 1500: Patronage, Production, Competition." In Wege zum illuminierten Buch. Herstellungsbedingungen für Buchmalerei in Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit, ed. Christine Beier and Theresia Kubina, 221-244. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2014.

________. "Benedetto Bordon and the 'San Nicolò Antiphonaries': New Discoveries. " In Il codice miniato in Europa. Libri per la chiesa, per la città, per la corte, ed. Giordana Mariani Canova and Alessandra Perriccioli Saggese, 569-585. Padova: Il Poligrafo, 2014.

Billanovich, Myriam. "Bordon, Benedetto." In Dizionario biografico degli italiani 12 (1970): 511-513.

Harper, John. The Forms and Orders of Western Liturgy from the Tenth to the Eighteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Mattioli, Emilio. Luciano e l'umanesimo. Istituto Italiano per gli studi storici series 31. Naples: Nella sede dell'Istituto, 1980.

Singing the Antiphonary

Gallery