Censure & Camouflage

Note: Some materials displayed on this page contain fascist symbols. In context, they are used for a subversive, anti-fascist purpose, but we recognize that this imagery is culturally sensitive and may be offensive. This is not an endorsement from the library but offered as a method to confront challenging histories associated with the objects through scholarship and discussion. Please use your discretion while exploring this page.

Mass production and the information on the title page made books identifiable with one glance. As such, print publications also lent themselves to be subject to control. Where rights to freedom of expression were or are not enshrined, printers often had to submit their products to the authorities for review and approval. At any rate, if the books they printed were said to violate social, political, religious, moral, or other codes, they could face repercussions.

Already in the early history of print, printers developed ingenious ways to disguise books with possibly controversial or subversive subject matter. In this sense, camouflage refers to the purposeful obfuscation of a book’s contents on the title page in order to allow for its covert distribution.

Strategies of deception in publishing challenge not only societal standards, but also the standards of the title page. Title pages promise readers certainty, if not legally binding information. Yet various restrictions forced and still force printers to hide or subtly signal the true character of their books. The truth remains up to the reader to discover.

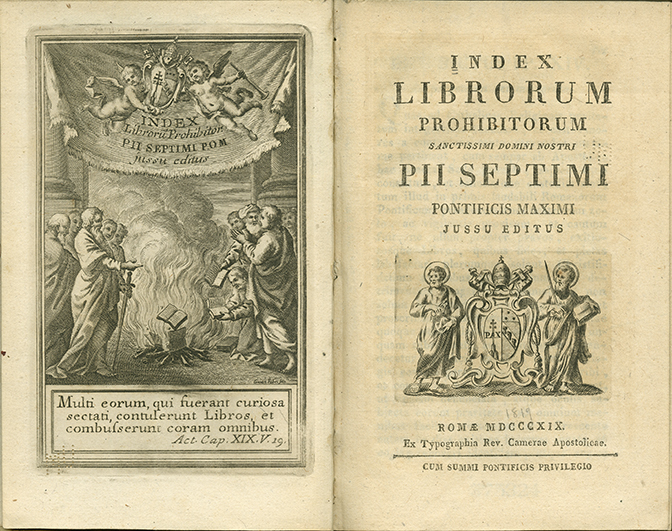

Facing the title page of this volume is a detailed scene of a book burning. A group of men are shown gathered around a bonfire, throwing open volumes into the flames. At the top of the image is a banner with the book’s Latin title, "Index Librorum Prohibitorum," and two cherubs carrying the coat of arms of Pope Pius VII, who was head of the Catholic Church from 1800 to 1823. On the right-hand page, the book’s title appears in large black letters. The publication information is in a smaller font at the bottom, beneath another image of Pius VII’s coat of arms.

The history of books is, among other things, a history of efforts to ban books. The Index of Prohibited Books, issued by Catholic authorities since the mid-sixteenth century until 1966—the item shown here dates to the early nineteenth century—served as such instruments of control. Indices contain the titles of publications to be censored or confiscated. Such lists aided religious and other authorities in controlling a market so vast that it eluded their grasp. Initially, indices grouped titles according to subject matter (theology, erotica, etc). Later, as in this case, the index was strictly alphabetical.

Title pages with their rendition of titles and author’s names played an important role when censoring books. After all, they allowed censors to identify certain prints unmistakably. In fact, this and similar volumes preface the index with a set of rules that include the following from the sixteenth century: "in the future no book shall be printed that does not feature upfront the first name, last name, and residence of the author [and printer]."

In this case, the title page is paired with a frontispiece of a book burning. This image legitimates the destruction of books, as mandated in this book, by reference to practices among early followers of Christ.

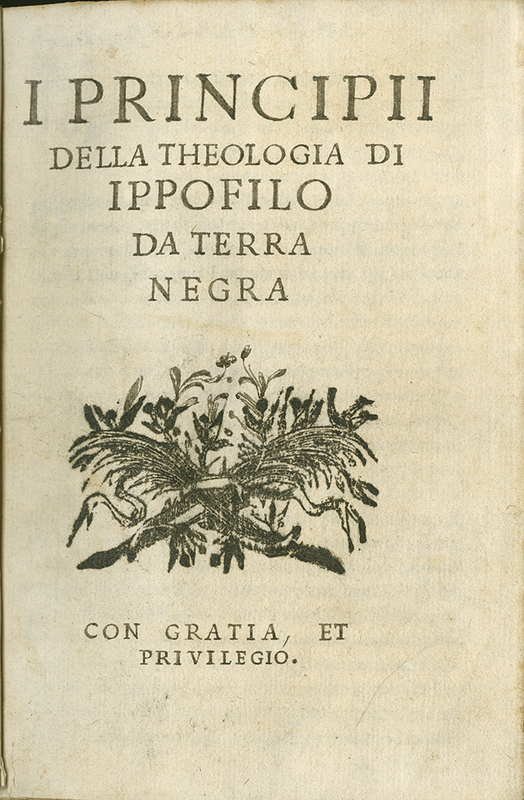

The title of this book, "I principii della Theologia," is printed in large black capitals at the top of the page, followed by the author’s pseudonym, "Ippofilo da Terra Negra." A botanical printer’s ornament, featuring two crossed bundles of foliage, occupies the middle of the page, above the Latin phrase: "CON GRATIA ET PRIVILEGIO."

As this unassuming title page demonstrates, texts by religious reformers made inroads in Catholic Europe via print. This volume is an Italian translation of Philip Melanchthon's Loci Communes, a prominent early modern textbook of rhetoric. Published in an undisclosed location, most likely in Venice, the book appeared in print without authorization, despite the legal formula cum gratia et privilegio ("with permission and legal protection") on the title page which suggests otherwise. In order to avoid censorship or prosecution, the unknown publisher obfuscated the volume's Protestant author, though his famous name could be decoded easily. The Ippofilo of the title is an anagram for Filippo, while da terra negra ("of black earth") is a literal translation of Melanchthon’s surname into Italian. Schwarzerde or "black earth" was his family’s German name, which translates as Melanchthon in Greek, a self-fashioning practice common among scholars at the time.

What you see is exceedingly rare. Only two copies of this camouflage publication have survived the passing of time.

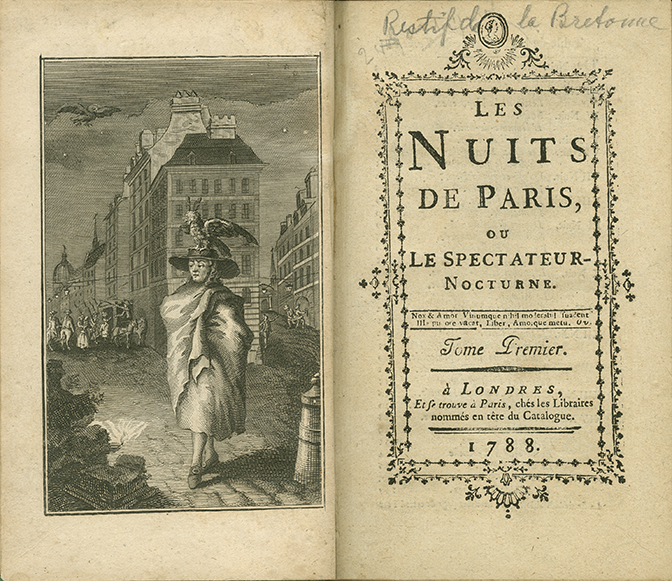

Facing the title page of this volume is an image of a man wrapped in a cloak with a bird perched on his wide-brimmed hat. Behind him we see elegant buildings and the cobble-stoned streets of pre-revolutionary Paris, with other figures visible in the distance. Another bird soars overhead in the dark night sky. The right-hand page features the title and other front matter, surrounded by a delicate floral border.

On this frontispiece to the left of the title, the author appears in a camouflage coat, a compelling variation on the author’s printed likeness with its promise that we can meet the person behind the book (see the previous section on Images Upfront). His portrait captures this eighteenth-century printer, publicist, prolific writer, and pornographer—a word Restif de la Bretonne coined—as an explorer of one of the largest cities of the time, Paris, by night—therefore the owl on his hat and the title, The Nights of Paris. Shadowy figures populate the scene's background, as tales of erotic adventures and urban mishaps loom. What we see is not the City of Lights of the nineteenth century but a dark corner of the metropolis before the French Revolution. On the title page, our tell-it-all urban explorer, the "nocturnal spectator" of the title, combined a firework of fonts in an idiosyncratic, if not antiquated, style. The information provided to the potential buyer or reader possibly contains an element of camouflage: the place of publication is given as London when in fact the book is likely to have been produced in France.

This volume was once owned by the "State Psychopathic Hospital at the University of Michigan."

Compare this page with the other examples of authors' portraits in "Imagery Upfront."

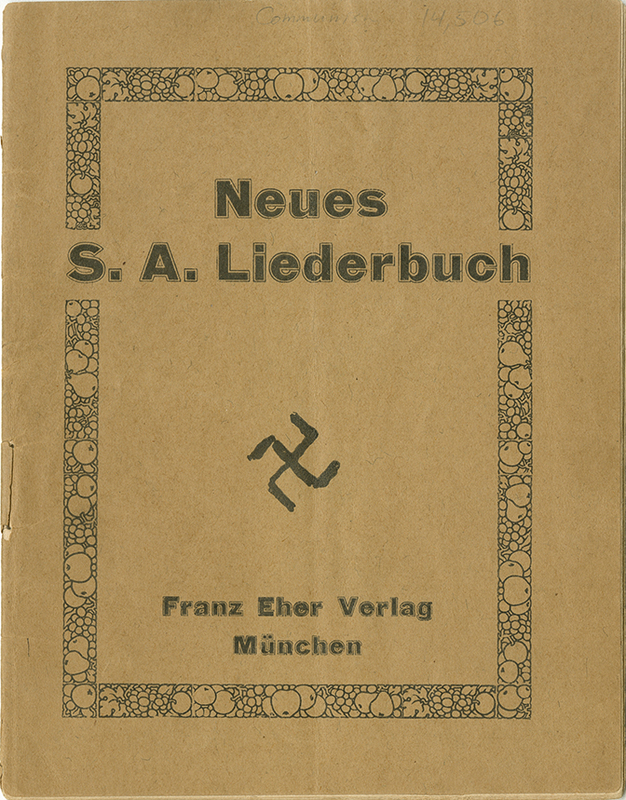

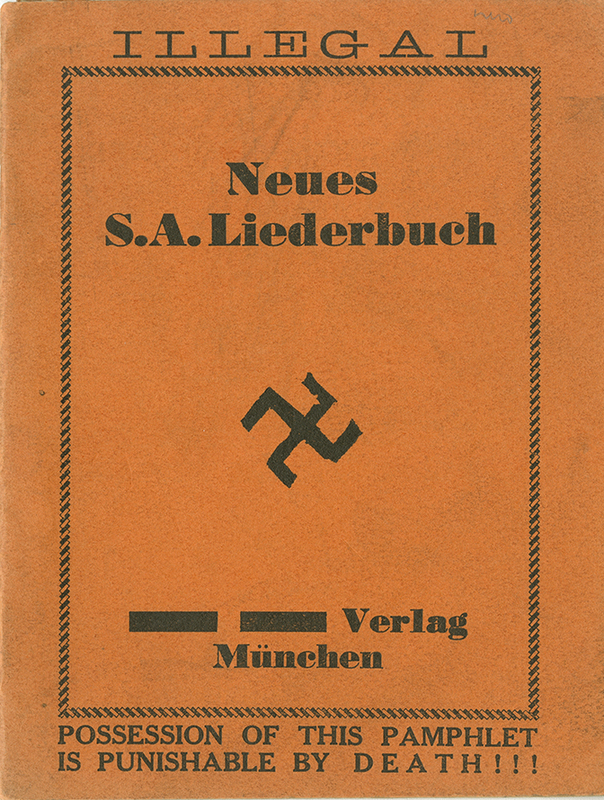

An innocuous border of grapes and other fruits surrounds the German title, "Neues S.A. Liederbuch," on this yellowish-brown cover. In the center is a swastika, beneath which information about the publisher is listed. A faint crease down the middle is visible, showing signs of wear.

According to its title, this pamphlet contains a "new songbook" for storm troopers (SA) in National Socialist (NS) Germany. If you open the item, however, instead of music you will find a hodgepodge of small texts that ridicule life under Nazi rule. In other words, the cover of this anti-fascist pamphlet was designed to go undetected in a country where resistance against the regime was suppressed and the handling or ownership of such materials was severely punished.

A second glance suggests subtle signs that the publication's actual content differs from what the title page says. The pamphlet is thinner than an ordinary songbook; the ornament that frames the title with its fruit-like design appears strange for a piece of propaganda; the swastika depicted is reversed compared to NS convention. Also, the title alludes obliquely to the "new" SA of 1934, the year this pamphlet saw the light of day, when the storm troopers had been disempowered as the party consolidated its hold on the state. At any rate, in this case, the camouflage may be decipherable for the discerning eye, and purposefully so.

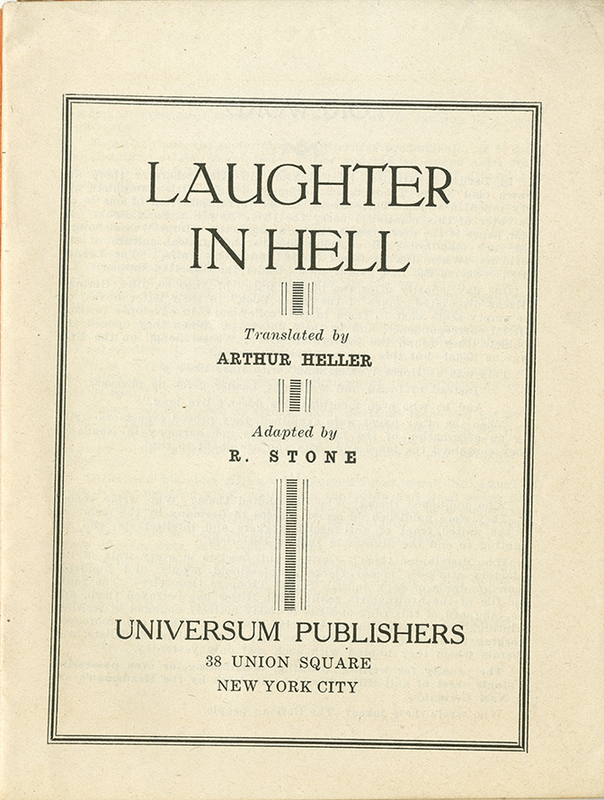

The lurid brown-orange cover of this text is emblazoned at the top of the page with the word "ILLEGAL," and at the bottom, also in capital letters, with the ominous warning: "POSSESSION OF THIS PAMPHLET IS PUNISHABLE BY DEATH !!!". In the center of the page is a swastika, beneath which the name of the publisher has been obscured by thick black censor bars. The border around the central text is simpler than in the example above, resembling a twisted black and white rope. Inside the pamphlet, however, the title page, seen on the right, is much more understated, with simple black text on white paper. It features the name of the text, the translator, the adapter, and the publisher, surrounded by a simple linear border.

This print advertises its supposed illegality on the cover—that it is not what the title says it is. This pamphlet appears to have been censored, but in fact camouflages its actual status. The publishers used censorship to arouse curiosity about the pamphlet’s contents in order to attract buyers and call attention to repression in National Socialist Germany. What you see is a translation of the item by the same title shown above, printed in New York in the mid-1930s as part of a short-lived publishing program by resisters against the Nazi state in the US (Universum Publishers). The blackened parts and supposed stamps on the title page of this orange-brown cover—brown was the color of the storm troopers—were not applied after publication but are in fact in the same ink as the rest of the item.

The pairing of the two items–one camouflage item published in Germany and an item published in English–as well as the text invite the reader to reflect on how resistance in an authoritarian regime may have functioned, and the difficulties of resisting in such a society. It was a call to action against the Nazi regime, not a support of it. But in a society that was heavily controlled and censored, resistance could only take subtle forms.

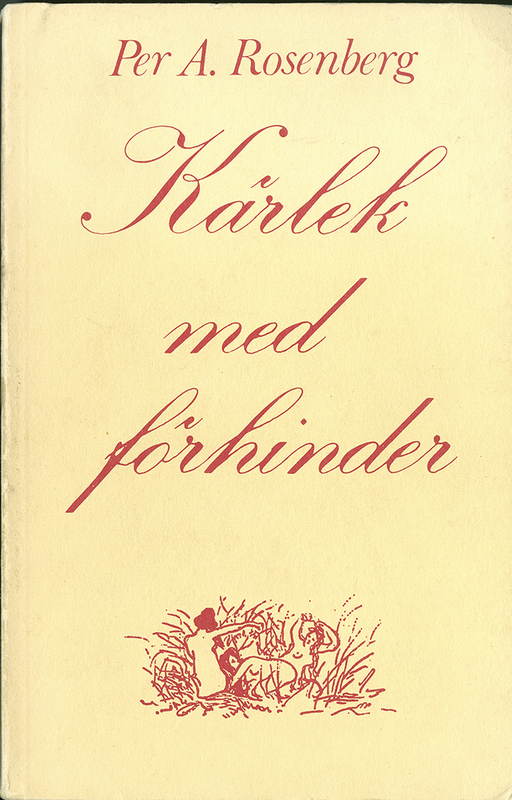

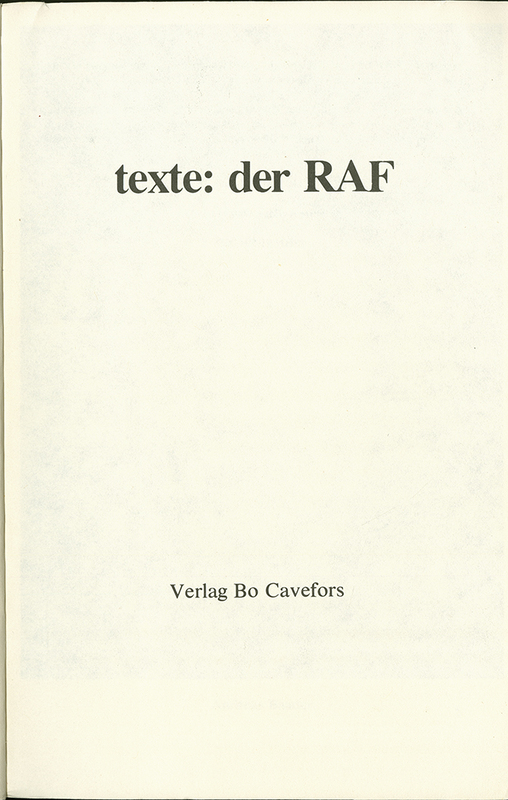

The yellow cover of this volume bears the (supposed) name of the text and its author in bright red ink and an elegant italic font. It is decorated at the bottom with a small image of three naked women bathing amidst tall grass. Inside, however, the first page of the text, located on the right, displays a different title in stark black letters: "texte: der RAF." Listed at the bottom of the page, is the name of the Swedish publisher, Bo Cavefors.

As a title Love with Obstacles sounds nothing if not innocuous. Yet the Swedish Kärlek med förhinder on the book’s cover masks the German content and title page, texte: der RAF, a collection of texts by the leaders of the Red Army Faction, a leftist guerrilla group in West Germany from their time in a maximum-security prison. These political messages and manifestos would have been illegal to distribute in the country at the time. Once the reader grasps the camouflage, Love with Obstacles and the somewhat risqué emblem on the cover take on a new, if not ironic, meaning. Still, the copyright information of this Swedish print features legitimate details, even if the ISBN number is incorrect. This book's "First Edition" is dated October 1977, which was the month of the RAF leaders' collective suicide while in prison. The book with their photographs may well have served as a postmortem tribute or an attempt to call on readers to continue their mission in the future.

Imagery Upfront

Acknowledgements