Searching for Printers' Errors

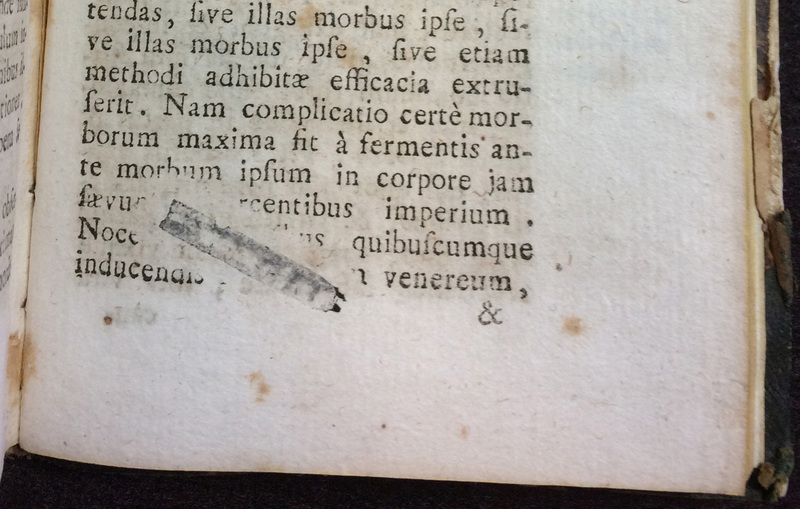

Ink marks left on the page by fallen types have been recorded in some copies of early printed books such as the one shown below. While it was not a widely-spread printing accident, it might have happen frequently enough to be a matter of concern among some printers like Alonso Víctor de Paredes, a Spanish compositor working in Spain in the second half of the seventeenth century. In his printing manual, Institution, and Origin of the Art of Printing, and General Rules for Compositors [Madrid: ca. 1680], Paredes mentions the cause of a fallen type when describing the type of errors a pressman should look for when examining his proof sheet: "The third sheet goes to the pressman so that it can be seen if, by mischance, the error was caused by a type that was pulled out by the ink balls, and which was then displaced, or if the sheet was put on the tympan the wrong way round."

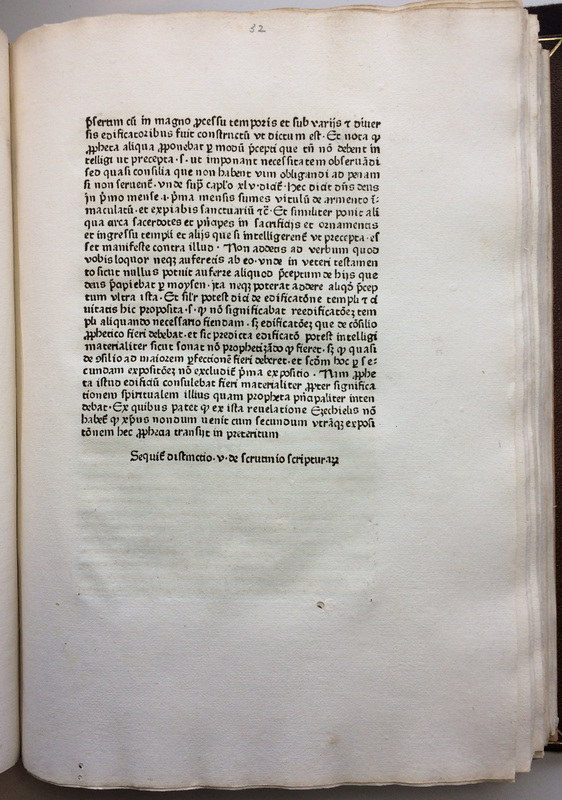

Casting off copy is the practice of estimating the length of the book to be printed by counting the words in the printer's copy or exemplar (manuscript or printed) and calculating the length of the entire text, considering the size of the paper, the format (folio, quarto, octavo, etc.), and the type size to be employed in the projected book. But some terrible mistakes or miscalculations might happen. If a casting off ends up being "short", it means that the compositor needs to add extra spaces to fill the page. Conversely, if it is "long", that is, if there are too many words to fit in the page, the compositor needs to shorten the extra text by inserting abbreviations. In the following images, we see an example of a casting off becoming too short. Since the page on display below is followed by a blank page, the printer, Johann Mentelin, inserted an explanatory line describing the content to follow, so that the reader should not assume that the blank space suggests that text is missing. Thus, Mentelin inserted the line: Sequit(ur) distinctio V de scrutinio scriptur(arum). In other words, "to follow is distinctio V de Scrutinium scripturarum", which is precisely the title of the chapter following the blank page.

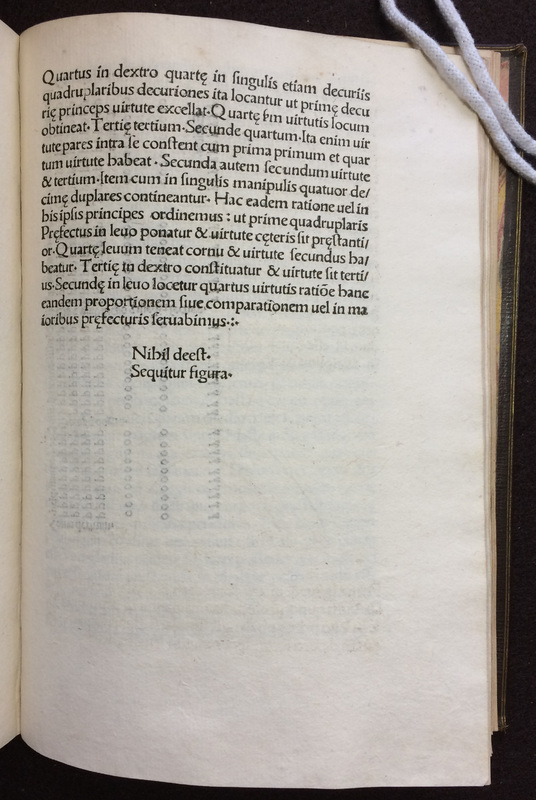

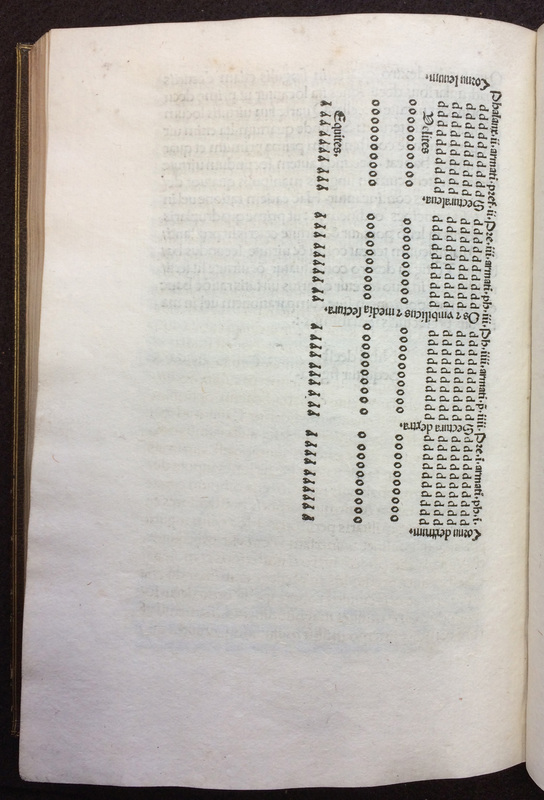

In 1487 the German printer working in Rome, Eucharius Silber, published a series of four Latin military treatises originally designed to be bound in a single volume, which is cataloged under the title, Scriptores rei militaris, sive Scriptores veteres de rei militari. Next is a new example suggesting that the printer seems anxious to assure the reader that the blank space in the lower half of the page does not indicate a missing text. Accordingly, Silber added the following warning: Nihil deest. Sequitur figura. "Nothing is missing. A figure to follow."

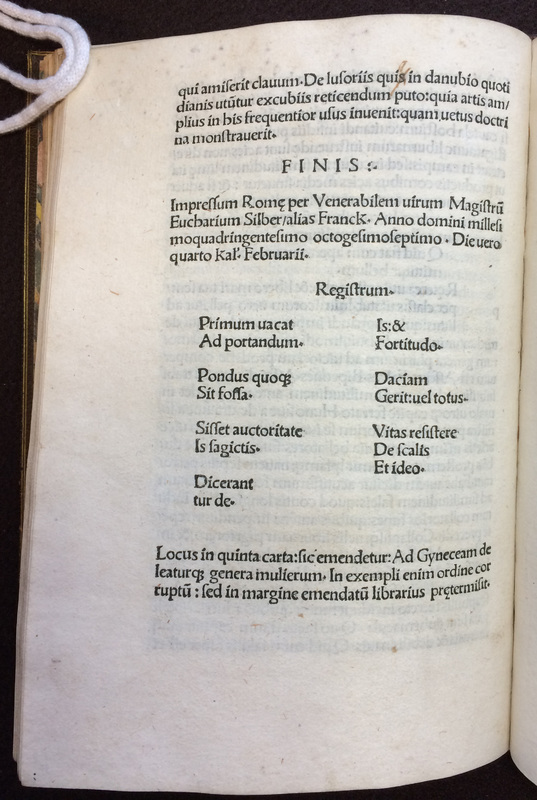

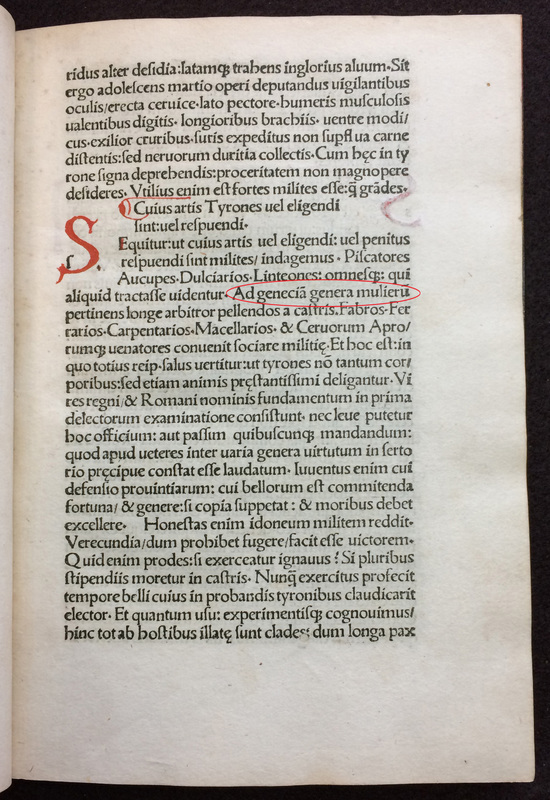

On display below is the last page of Vegetius' military treatise, De re militari, which is the first work of the already mentioned four-treatise volume published by Eucharius Silber in 1487. The page shows two features that were fairly common in incunables, that is, in books printed in the fifteenth century. Firstly, we find the colophon, here recording the name of the printer and the date of publication. Secondly, is the registrum, which singles out each quire by including their respective first words: a useful tool for the binder! Additionally, as a brief example of the so-called "errata sheet", the printer included instructions about how to correct an error that was not detected before or even during printing. The last three lines can be tranlated as follows: A section in the fifth folio should be corrected like this: Ad Gyneceam de leaturq(ue) genera mulierum. While it was wrong in the text of the manuscript, the copyist failed to see the emendation on the margin.

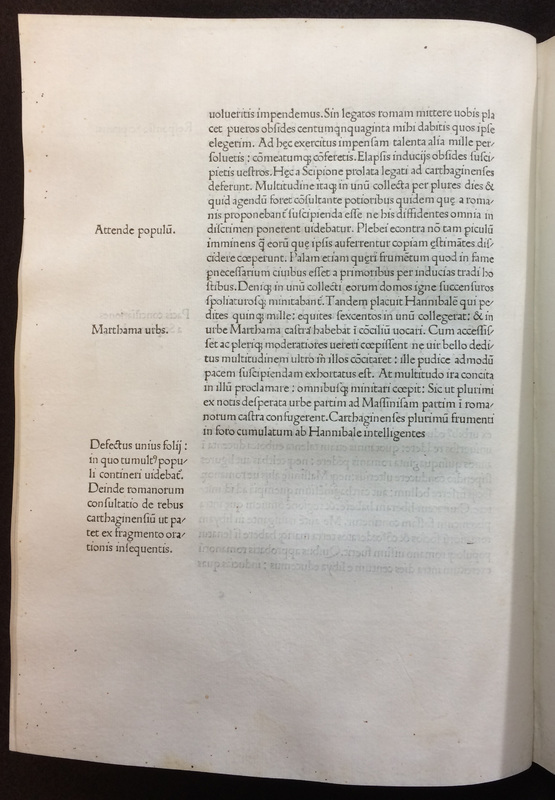

However, the presence of a sudden blank page within the text does not necessarily mean that the compositor made a miscalculation when casting off. For instance, in an early printed edition of Petrus Candidus Decembrius' Latin translation of Appian's Historia Romana published in Venice in 1477, the blank spaces we see in the pages below are replicating the manuscript that was used as a printer's copy or exemplar for this edition. Thus, we can read on the lower left margin a warning to the reader, which can be transtaled as follows: "The absence of one leaf in which it seemed to contain people's uproar followed by the Romans' deliberation about the affairs of the Carthaginians as it is shown from a section of the following speech." In the manuscript tradition, scribes often left blank pages to acknowledge gaps or lacunae in the trasmission of the text.

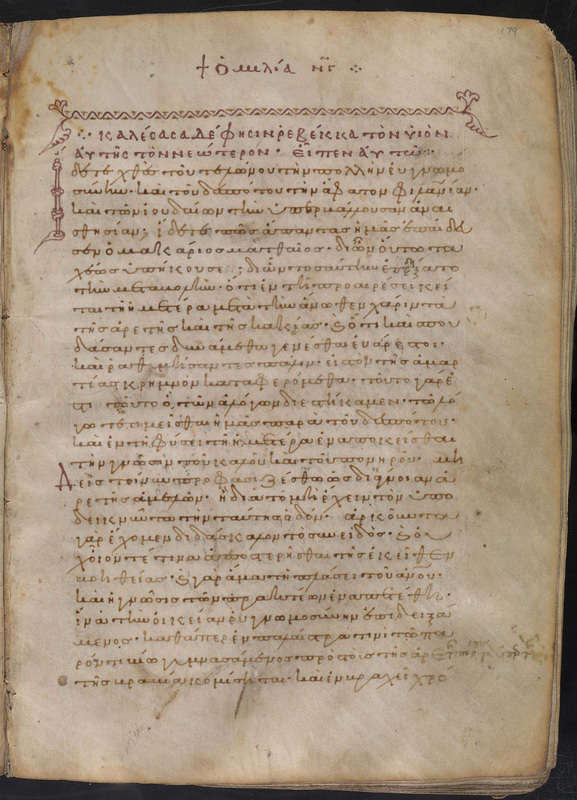

Marks of Correction: How to fix a Manuscript Line

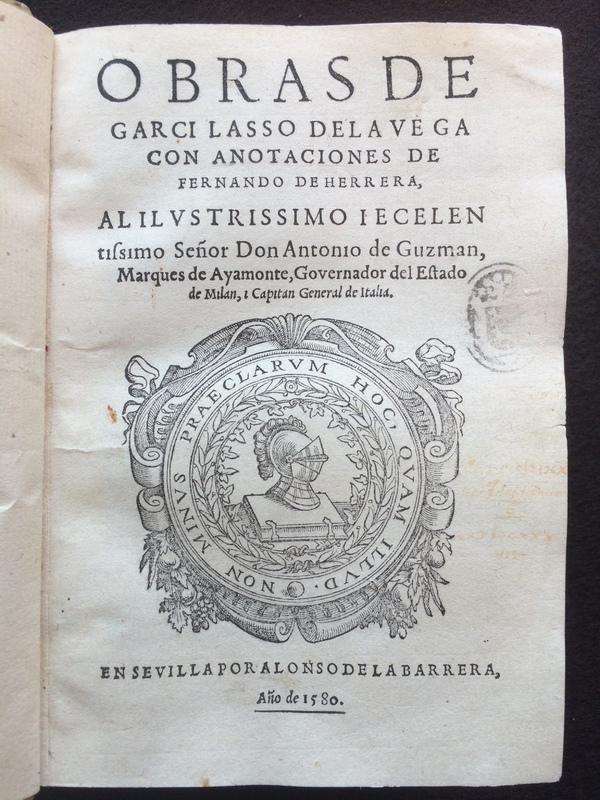

Marks from an Anxious Corrector: Fernando de Herrera