Imagining the Other at Home I

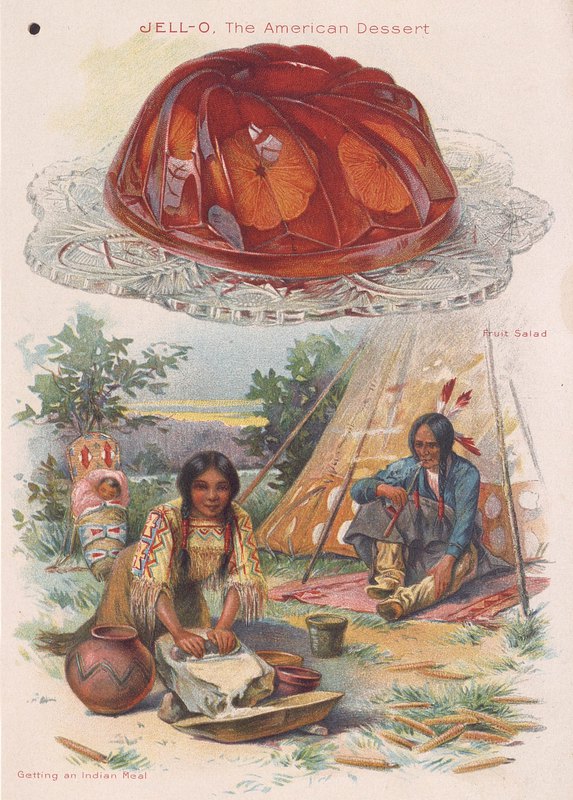

Although Plains Indians accounted for only five percent of the indigenous population, advertising iconography followed the lead of wider white culture in largely relying on a mash-up of ideas imagined to be associated with Plains Indian culture, as illustrated in Getting an Indian Meal. A beautiful woman gazes at the reader, sitting forward to use her body weight in grinding corn. Nearby, a contented papoose dozes on a cradle board. A befeathered Indian man sits in front of a tepee, smoking a peace pipe. Above this scene floats a fruited Jell-O mold, sliced oranges and bananas suspended in strawberry Jell-O. In the tradition of Wild West Shows and forced assimilation, the accompanying text waxes nostalgic about the Indians as a “vanishing race.”

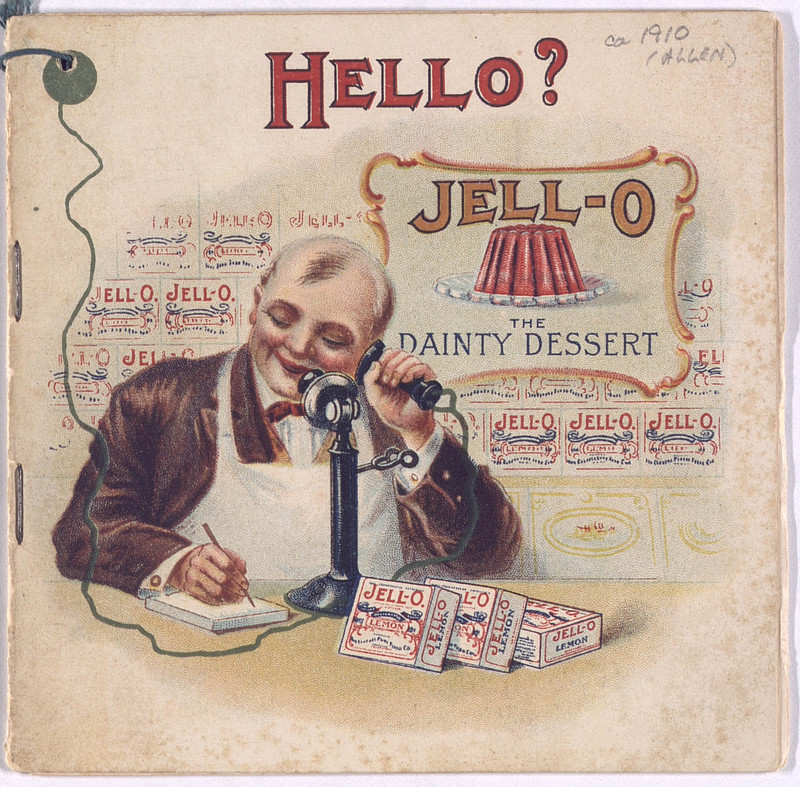

In the Hello? Jell-O: The Dainty Dessert booklet recipes are interspersed with illustrations of customers telephoning the grocer to place orders of Jell-O. The proverbial jolly grocer illustrates the front page of the booklet (the desserts are the dainty), where the cord from his candlestick telephone visually connects him with his callers, as the telephone cords segue into the cord that ties the booklet together. The callers are housewives, children, Italian chefs and maids. In this image a black woman in a lace apron and cap, perhaps signifying a fine housekeeper, places her order. Three desserts are shown – peach, cherry, and chocolate – all in elaborate molds decorated with cream and fruit. The stereotypical (“Yas Sah”) language is common in these advertisements, as is the depiction of black women preferring peach Jell-O.

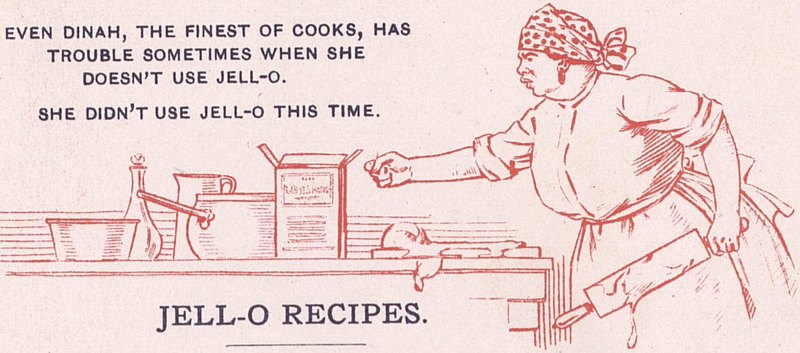

This 1913 booklet positions Jell-O as the solution to failed desserts – when the pudding is burnt and the pie went funny, make Jell-O, because “nothing goes wrong with Jell-O.” Line drawings of exhausted housewives, frustrated maids, and disappointed children illustrate the perils of non-Jell-O desserts. Recipes are provided for elaborate sweet and savory dishes – including marbled Jell-O, Jell-O made with pureed greengage plums, and stuffed tomato salad. The middle of the book is dominated by a full color illustration of Peach Jell-O with a resplendent bandana-wearing Mammy/cook. Above her is the line: “Yo’ ole Aunt Dinah never made nothin’ better’n dat.” On the following page, the titular Aunt Dinah is scowling and brandishing her rolling pin: “Even Dinah, the finest of cooks, has trouble sometimes when she doesn’t use Jell-O.” Popularized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and through blackface minstrelsy, the Mammy archetype peaked with Hattie McDaniel’s Oscar-winning performance in Gone with the Wind (1939). Jell-O’s Aunt Dinah may have been inspired by the pancake-promoting Aunt Jemima character, played in promotions for decades by Nancy Green.

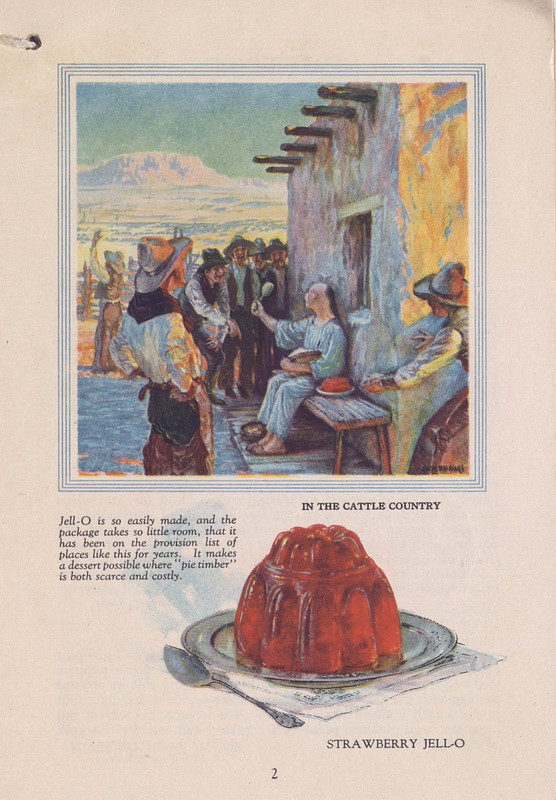

A Chinese camp cook sits on a bench, surrounded by laughing cowboys in In the Cattle Country, the first of the locations presented in Jell-O America’s Most Famous Dessert: At Home Everywhere. He is wearing loose-fitting cotton, neither Chang Pao nor Ma Gua, and his hair is styled into a queue (bianzi 辮子). 1922, the year of the publication of this booklet, was a potent year to be wearing the queue. Although it had been in steady decline since 1911, the removal of the 'queue' became, as historian Michael R. Godley put it “one of the better-known symbols of the fall of imperial rule, modernization and political change” in China. And it was in 1922 that the last Emperor of China, Henry Pu Yi, cut off his queue. If real, this Chinese worker would be either making a radical political statement or be rather behind the times. He is, however, made modern by the large bowl of Jell-O which sits next to him. Modern, but simple: “Jell-O is so easily made, and the package takes so little room, that it has been on the provision list of places like this for years.” A large strawberry Jell-O fills the bottom of the page.

Recreational camping grew enormously in popularity during the first quarter of the twentieth century US, most famously with the repeated car-camping trips shared by Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs between 1914 and 1924. In Among the Redwoods, a racially ambiguous woman un-molds Jell-O on the massive stump of a cut redwood. Her only kitchen equipment is an open fire tended by her companion, with steaming pot above the flames. The accompanying text claims that: “Wherever hot water is available, even in a ‘Gipsy’ auto camp, Jell-O may be enjoyed.” The Ford and Edison entourage eventually grew to fifty vehicles, and media attention led to the end of the Firestone’s treasured “simple, gipsy-like fortnights.” Perhaps these were the “other circumstances” in which Jell-O envisioned the elaborately molded four-layered Neapolitan shown at the bottom of the page.

Imagining the Other at Home II