Imagining the Other at Home Overview

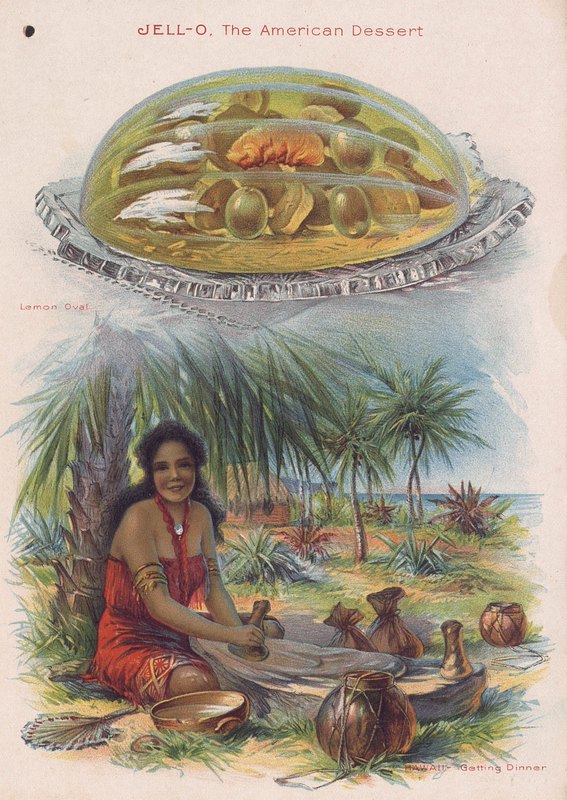

In the aftermath of World War One, it is popularly imagined that American turned away from the world; this inwards focus is strikingly absent from the Jell-O advertising of the era, which is remarkably global in outlook. Orientalist, and racist, but global nonetheless. From Dutch kitchen scenes to Company Luncheons with Buddha figurines, the Other is imagined; sometimes consuming Jell-O, sometimes too Other to be consuming it.

White American culture (building on work by Eric Lott, in particular Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class) was endlessly fascinated and fearful of what they imagined the Other to be, and continually appropriated the imagined authority and/or attributed power. In melting-pot America, Jell-O advertising imagined the racialized Other at home – he as the archetypical Chinese Cook; she as the mythologized Southern Mammy, as geographic -- from the extreme territory under the Northern Lights to the windswept Great Plains, and temporal – shown in both contemporary and historical settings. The Jell-O brand is thus thickly ubiquitous – both white and non-white, both everywhere and at home, both historical and contemporary – until the viewer fixes their meanings.

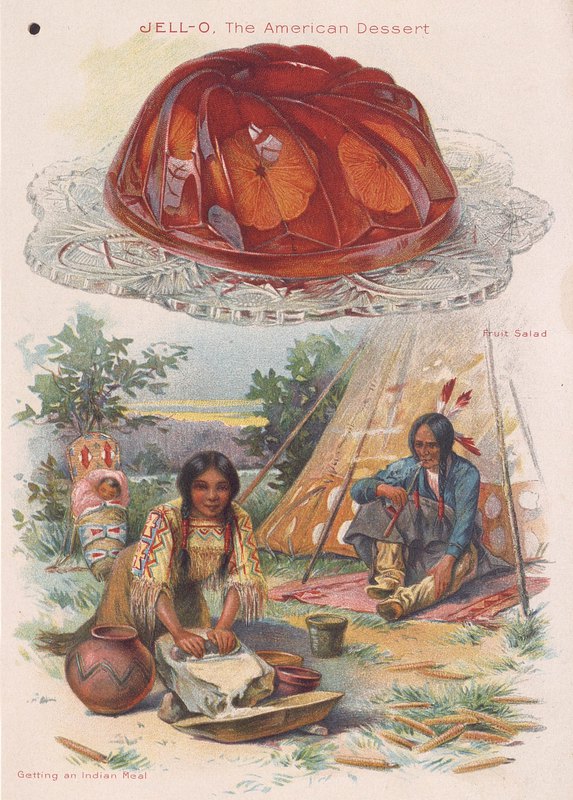

Imagining the Other at Home I

Although Plains Indians accounted for only five percent of the indigenous population, advertising iconography followed the lead of wider white culture in largely relying on a mash-up of ideas imagined to be associated with Plains Indian culture, as illustrated in Getting an Indian Meal. A beautiful woman gazes at the reader, sitting forward to use her body weight in grinding corn. Nearby, a contented papoose dozes on a cradle board. A befeathered Indian man sits in front of a tepee, smoking a peace pipe. Above this scene floats a fruited Jell-O mold, sliced oranges and bananas suspended in strawberry Jell-O. In the tradition of Wild West Shows and forced assimilation, the accompanying text waxes nostalgic about the Indians as a “vanishing race.”

In the Hello? Jell-O: The Dainty Dessert booklet recipes are interspersed with illustrations of customers telephoning the grocer to place orders of Jell-O. The proverbial jolly grocer illustrates the front page of the booklet (the desserts are the dainty), where the cord from his candlestick telephone visually connects him with his callers, as the telephone cords segue into the cord that ties the booklet together. The callers are housewives, children, Italian chefs and maids. In this image a black woman in a lace apron and cap, perhaps signifying a fine housekeeper, places her order. Three desserts are shown – peach, cherry, and chocolate – all in elaborate molds decorated with cream and fruit. The stereotypical (“Yas Sah”) language is common in these advertisements, as is the depiction of black women preferring peach Jell-O.

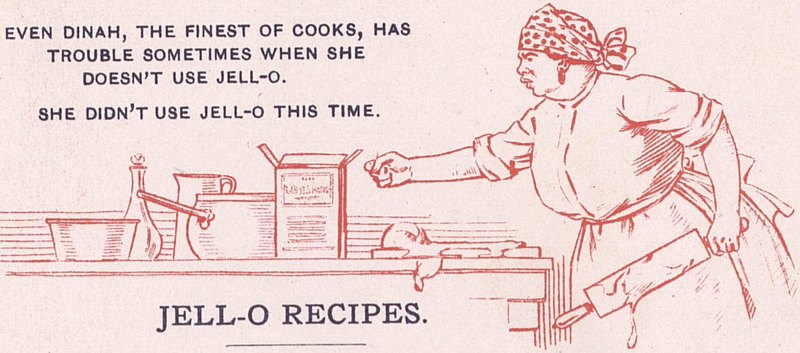

This 1913 booklet positions Jell-O as the solution to failed desserts – when the pudding is burnt and the pie went funny, make Jell-O, because “nothing goes wrong with Jell-O.” Line drawings of exhausted housewives, frustrated maids, and disappointed children illustrate the perils of non-Jell-O desserts. Recipes are provided for elaborate sweet and savory dishes – including marbled Jell-O, Jell-O made with pureed greengage plums, and stuffed tomato salad. The middle of the book is dominated by a full color illustration of Peach Jell-O with a resplendent bandana-wearing Mammy/cook. Above her is the line: “Yo’ ole Aunt Dinah never made nothin’ better’n dat.” On the following page, the titular Aunt Dinah is scowling and brandishing her rolling pin: “Even Dinah, the finest of cooks, has trouble sometimes when she doesn’t use Jell-O.” Popularized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and through blackface minstrelsy, the Mammy archetype peaked with Hattie McDaniel’s Oscar-winning performance in Gone with the Wind (1939). Jell-O’s Aunt Dinah may have been inspired by the pancake-promoting Aunt Jemima character, played in promotions for decades by Nancy Green.

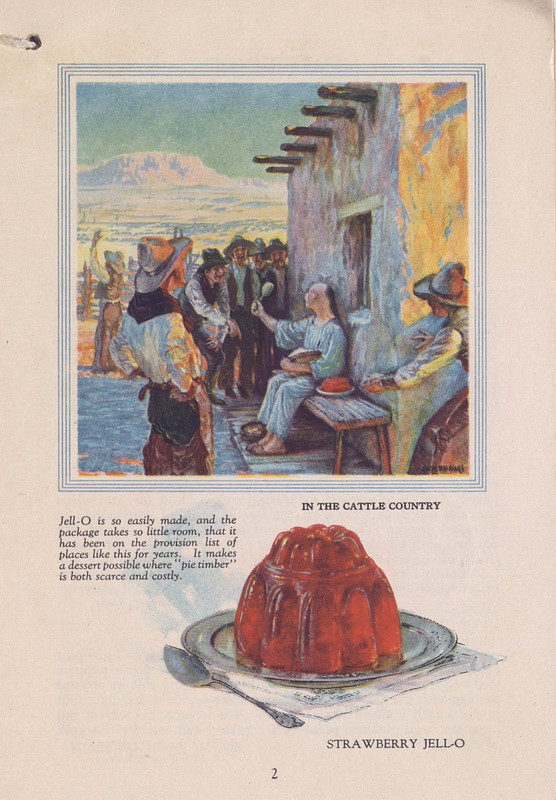

A Chinese camp cook sits on a bench, surrounded by laughing cowboys in In the Cattle Country, the first of the locations presented in Jell-O America’s Most Famous Dessert: At Home Everywhere. He is wearing loose-fitting cotton, neither Chang Pao nor Ma Gua, and his hair is styled into a queue (bianzi 辮子). 1922, the year of the publication of this booklet, was a potent year to be wearing the queue. Although it had been in steady decline since 1911, the removal of the 'queue' became, as historian Michael R. Godley put it “one of the better-known symbols of the fall of imperial rule, modernization and political change” in China. And it was in 1922 that the last Emperor of China, Henry Pu Yi, cut off his queue. If real, this Chinese worker would be either making a radical political statement or be rather behind the times. He is, however, made modern by the large bowl of Jell-O which sits next to him. Modern, but simple: “Jell-O is so easily made, and the package takes so little room, that it has been on the provision list of places like this for years.” A large strawberry Jell-O fills the bottom of the page.

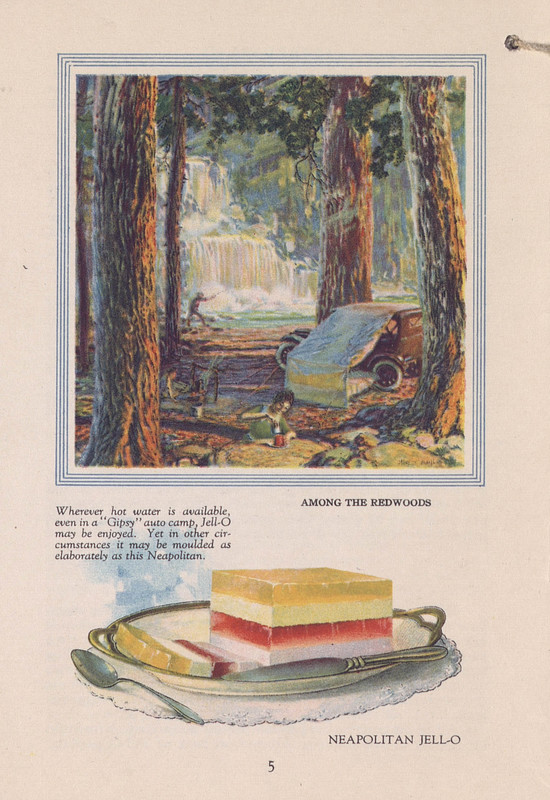

Recreational camping grew enormously in popularity during the first quarter of the twentieth century US, most famously with the repeated car-camping trips shared by Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs between 1914 and 1924. In Among the Redwoods, a racially ambiguous woman un-molds Jell-O on the massive stump of a cut redwood. Her only kitchen equipment is an open fire tended by her companion, with steaming pot above the flames. The accompanying text claims that: “Wherever hot water is available, even in a ‘Gipsy’ auto camp, Jell-O may be enjoyed.” The Ford and Edison entourage eventually grew to fifty vehicles, and media attention led to the end of the Firestone’s treasured “simple, gipsy-like fortnights.” Perhaps these were the “other circumstances” in which Jell-O envisioned the elaborately molded four-layered Neapolitan shown at the bottom of the page.

Imagining the Other at Home II

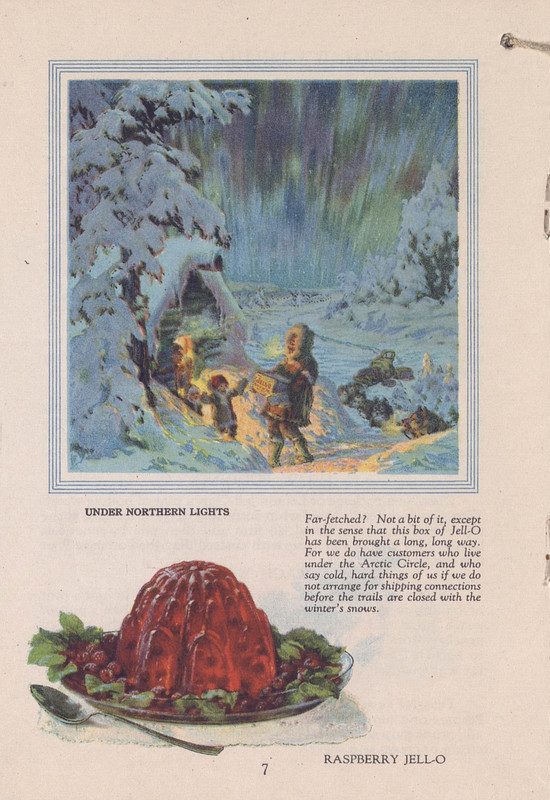

Raspberry Jell-O served on a glass platter decorated with fresh raspberries and their leaves stands in contrast to the snowy scene in Under Northern Lights. A well-bundled figure arrives carrying a box of Jell-O, met by two excited children and a woman. Warm light pours out of the house and illuminates the snowy scene. “Far-fetched?” viewers are imagined to wonder, “Not a bit of it, expect in the sense that this box of Jell-O has been brought a long, long way.” Reader doubts about the existence of these customers are assuaged: “...we do have customers who live under the Arctic Circle, and who say cold, hard things of us if we do not arrange for shipping connections before the trails are closed with the winter’s snows.” Cold, hard words can be avoided with soft Jell-O, though fresh raspberries may be available only in season.

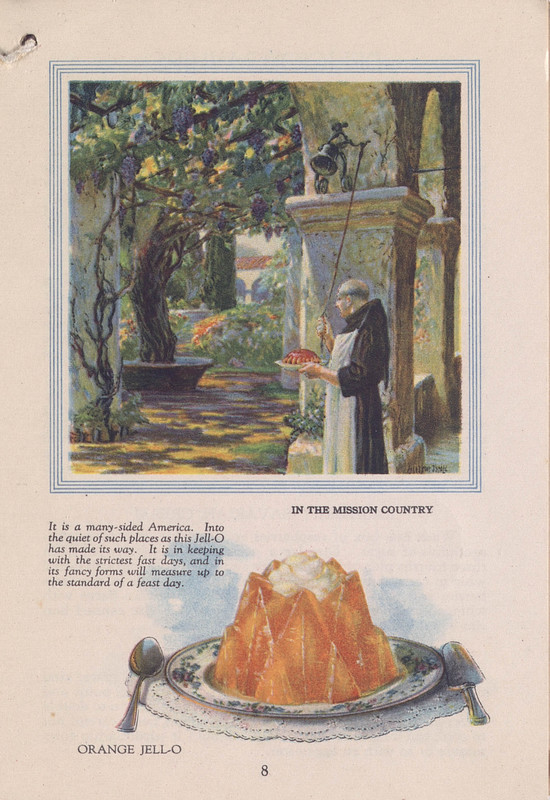

In light dappled by grapevines and verdant trees a Padre rings a bell In the Mission Country. In his other hand, he holds a large Orange Jell-O dessert, mirroring the illustration at the bottom of the page. Simple Jell-O, we are told, “is in keeping with the strictest fast days, and in its fancy forms will measure up to the standard of a feast day.” The dominant American narrative of westward expansion sometimes obscures the older European colonization of the western states. San Diego, for example, was permanently occupied by the Spanish in 1769. Fast day or feast day, this Jell-O is obviously the same product, remade and re-imagined, versatile, adaptable and suited to the “many-sided America.”

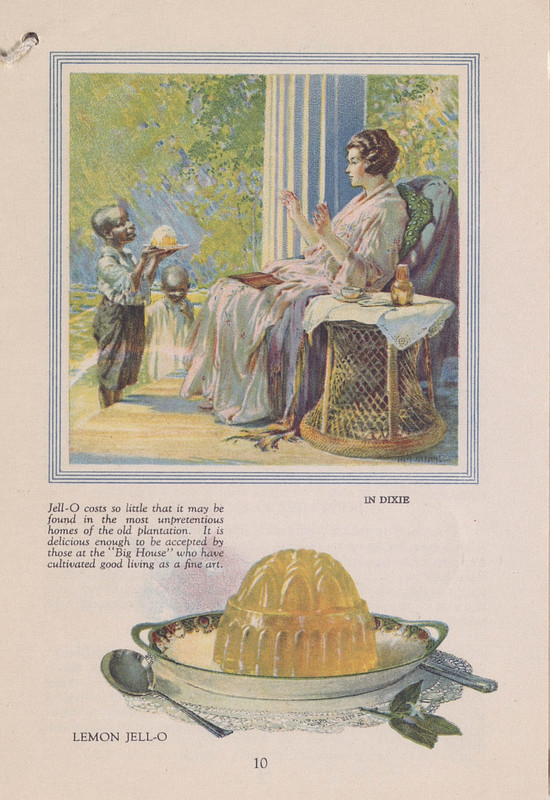

Originally published in 1922 as "Mammy Sent Dis Ovah" this Angus MacDonall piece, republished here as In Dixie, shows a white woman reclining in a large chair. She is dressed in simple silk robes, with an open book resting on her lap. A cup, a plate and a pitcher sit on her cane side-table. Her elegance is interrupted by the arrival of two black boys, one of whom presents a golden Lemon Jell-O. Thickened with racist nostalgia for an imagined past, “Jell-O costs so little that it may be found in the most unpretentious homes of the old plantation. It is delicious enough to be accepted by those at the ‘Big House’ who have cultivated good living as a fine art.”

On the Prairies two women look out over a vast dry land. Plates, flatware, four large stacks of bread, red Jell-O, and several pitchers fill the table behind the women. The vast land, however, is shown empty of people. This is the American Farm Wife, symbol of the lonely plains, source and upholder of plain hearty Good American Cooking, preparing a harvest-time supper for the hands. The frugality of farm life is underscored by the text: “In the Wheat Belt a thing has to prove its worth before it finds a place on a table like this.” The Jell-O dish accompanying this illustration is not a dessert, but rather Imperial Salad. A concoction of Lemon Jell-O mixed with vinegar, canned pineapple, pimentos and salted shredded cucumber, set in individual molds and dressed with cream salad dressing, Imperial Salad suggests the conquering of seasons, of good taste, and in this setting, of the land.

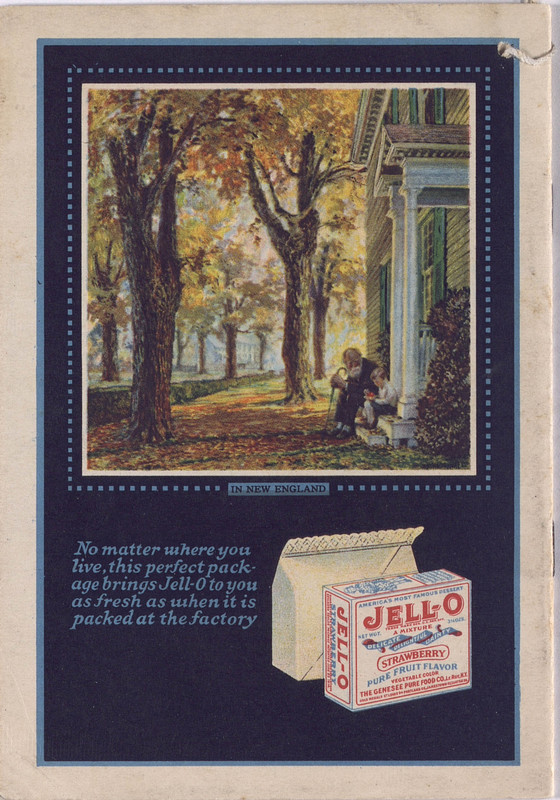

The back cover of Jell-O America’s Most Famous Dessert: At Home Everywhere is dominated by the fall foliage of New England. A child and an old man, perhaps his grandfather, sit on the stoop of a substantial clapboard house. The illustration appears to have been influenced by the nationalistic sublime of the then-unfashionable Hudson River School of painting – wild and beautiful American landscapes, vast nature made both vaster and intelligible by tiny humans wielding mighty industry. The text of the advertisement focuses on production and distribution: “No matter where you live, this perfect package brings Jell-O to you as fresh as when it is packed at the factory.” Standardization and mechanization are ‘at home everywhere,’ in part because home is imagined as the same everywhere, in all the ways that matter. Jell-O’s America is bound together by this shared experience, a community imagined, and imaginable, through consumption and a gustatory experience repeatable and replicable.

Imagining the Other Overview

About the Exhibit