Production Overview

Progressive Era food advertising often relied on ideas of food purity, hygiene, sanitation and scientific production. For Jell-O, this meant images emphasizing the cleanliness and mechanization of production, and the modernness of the factory.Even the name (until 1923) the ‘Genesee Pure Food Company,’ asserts the purity of the product. This was an era of food fear – of fraud, of adulteration and of attempts at regulatory control like the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906). In this context, Jell-O cautioned its customers to ‘accept no substitute,’ and provided detailed descriptions of packaging so that consumers were not duped into buying lesser, counterfeit, or adulterated products. In what looks remarkably prescient, Jell-O’s constructions of purity extended to advertising that mapped the international sourcing of ingredients. Combined with advertisements focused on exotic settings, Jell-O thus helped furnish the American imagination about the world, while simultaneously hinting at American superiority.

Production

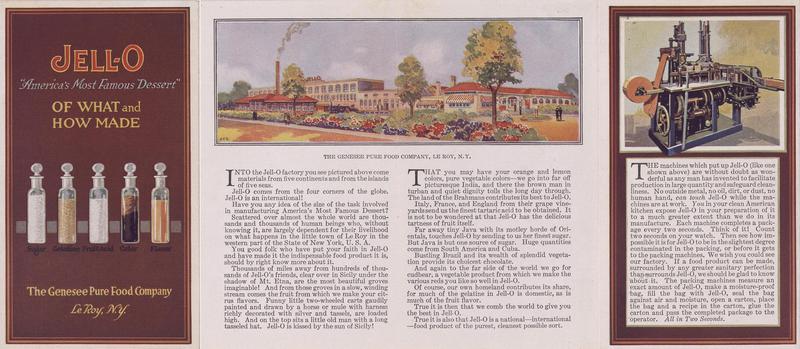

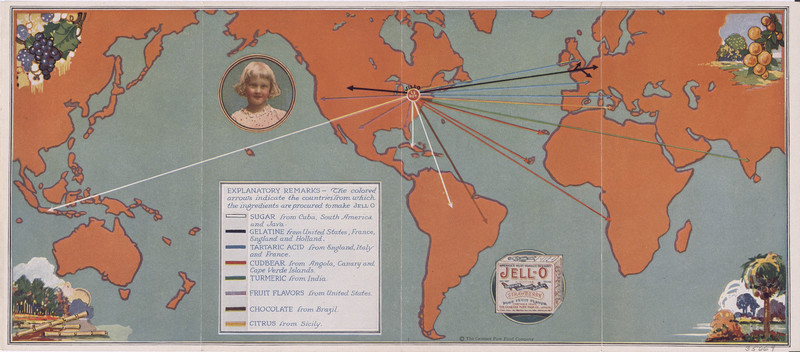

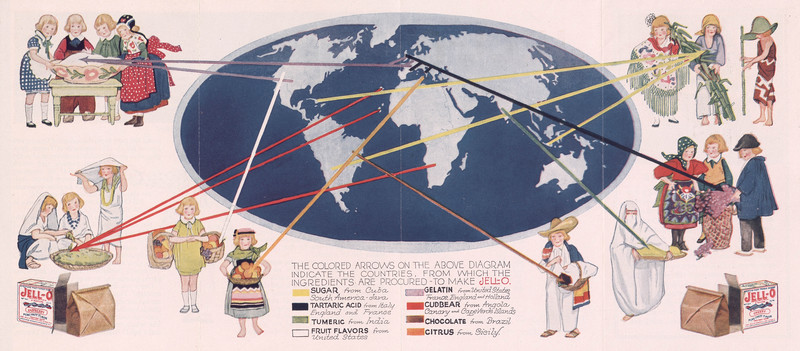

Images in Jell-O: Of What and How Made encapsulate three themes: modern, pure, and international. Five stoppered vials emphasize the modern with the essential ingredients (at the time): Sugar, Gelatine (as original), Fruit Acid, Color, and last, Flavor. As the pamphlet is unfurled, science (the vials) and production (the factory) are linked in a full page image of the Genesee Pure Food Company Factory. Smoke puffs signal a modern factory in action, ordered and imposing; industrial productivity softened by trees and gardens. The emphasis on the international is captured in the central text and the main illustration – mapping the origins of the those vials (see the following image). The final image is of the packing machine and it connects scientific manufacturing to hygiene in very explicit terms. “No outside metal, no oil, dirt, or dust, no human hand, can touch Jell-O while the machines are at work. You in your clean American kitchen expose Jell-O in your preparation of it to a much greater extent than we do in its manufacture.” Text echoes image, as readers learn that “Jell-O is a national – international – food product of the purest, cleanest possible sort.”

Taking Le Roy, New York as the center of the world, the map in Jell-O: Of What and How Made visually connects international ingredient producers to the Jell-O factory. Materials come “from five continents and from the islands of five seas” and “four corners of the globe,” making Jell-O “an international!” The map lists eight origins, including, turmeric from India, chocolate from Brazil, and sugar from Cuba, South America and Java. Java, like Cuba and India provides a touch of ‘quaint’ racialization: “Far away tiny Java with its motley horde of Orientals, touches Jell-O by sending us her finest sugar.” In a prescient summation of the global food system, Jell-O imported raw materials from all over the world. Readers are told that “scattered over almost the whole world are thousands and thousands of human beings who, without knowing it, are largely dependent for their livelihood on what happens in the little town of Le Roy in the western part of the State of New York, USA.”

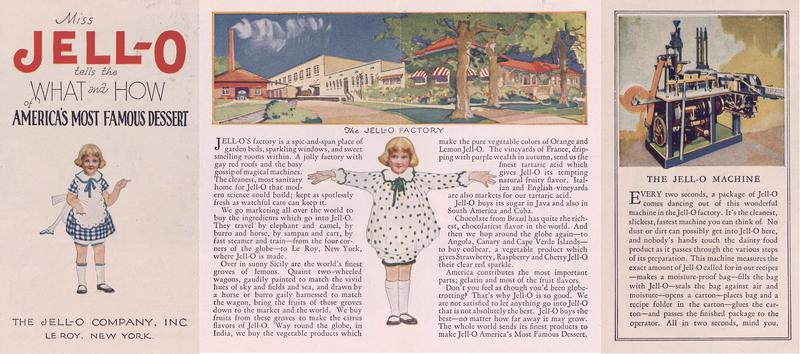

The folded pamphlet MissJell-O Tells the What and How of America’s Most Famous Dessert again connects science, the sourcing of goods and production. But this factory is of machines indistinguishable from magic, not of workers. A cartoon fantasy of: “a spic-and-span place of garden beds, sparkling windows, and sweet smelling rooms within. A jolly factory with gay red roofs and the busy gossip of magical machines.” On the back page the famous Jell-O packing machine again equates mechanization with sanitation: “It’s the cleanest, slickest, fastest machine you can think of. No dust or dirt can possibly get into Jell-O here, and nobody's hands touch the dainty food product as it passes through the various steps of its preparation.” There are apparently no human workers in Le Roy, New York

The Miss Jell-O Tells the What and How of America’s Most Famous Dessert pamphlet includes a full page map. Arrows show the sources of raw materials, which are illustrated by Miss Jell-O in various Jell-O-imagined national costume. Dressed in an imagined white niqāb and laden with turmeric, Miss Jell-O peers through eye-slits to embody India. Citrus from Sicily is captured by Miss Jell-O’s bare feet and colorful apron. Beyond hats and costumes, Jell-O ingredients: “travel by elephant and camel, by burro and horse, by sampan and cart, by fast steamer and train – from the four corners of the globe – to Le Roy, New York.” This is the logic of Jell-O colonialism -- native peoples in quaint costumes provide raw materials to feed the machines at the center of the Jell-O empire. America provides gelatin, fruit flavor and the consumer.

Polly Put the Kettle On: We’ll All Make Jell-O, a 1924 booklet with recipes and illustrations inspired by nursery rhymes, includes a center-fold about the production of Jell-O. There are four distinct images, from left to right - the packing machine, a sealed sachet of Jell-O, an open Jell-O box and the Jell-O girl, holding a package of Jell-O and a kettle. Both the capacity (forty-two machines, making thirty packagers per minute) and the steps of mechanization are detailed: “The Jell-O packing machines measure an exact amount of Jell-O, make a moisture-proof bag, fill the bag with Jell-O, seal the bag against air and moisture, open a carton, place the bag and a recipe in the carton, glue the carton and pass the completed package to the operator.” The humans at the factory are nearly invisible, yet Jell-O is so easy to make even a child can do it. All she needs is a packet of Jell-O and a water-filled kettle.

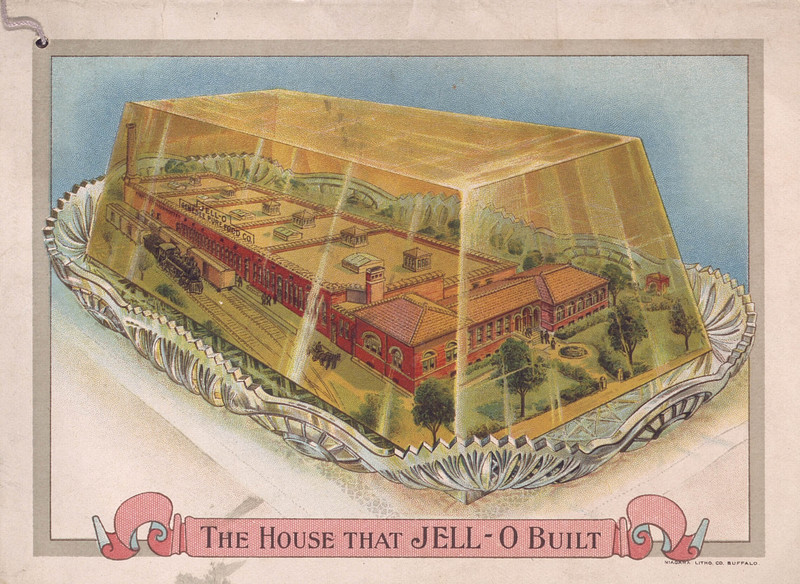

In the 1913 Jell-O America’s Most Famous Dessert booklet the back cover comprises a full-page illustration, printed sideways, entitled The House that Jell-O Built. What Jell-O built is a factory and garden, complete with trees, grass and garden ornaments - a freight train, a horse and trap, some workers, all suspended in a massive lemon-flavored cuboid. This mighty manor is the seat of the Jell-O empire, a symbol of industrial production and modernity. The neat brick factory set in manicured grounds negotiates tensions between technological machine and pastoral garden, enveloping physical, psychological and market space, in a tasty dessert treat.

Overview

Exotic Tales Overview