Political Retribution and Sanctions

The period of American sanctions beginning in 1990 under George H. W. Bush brutalized all levels of Iraqi society: the estimated human cost of these sanctions reached 1.8 million, caused by the severe restrictions on food and health infrastructure. Economic and educational opportunities dwindled. Once abundant, elite universities were forced to suspend the importing of new materials. Rapidly, their collections of scientific journals, research papers, and books became outdated, rendering the nation’s higher education alienated from the global academic community. The former luxuries of education-abroad became selective; access to positions and promotions depended on Ba’athi Party membership, which cost money, time, and safety. Economic recession decreased university spending; a professorial salary suddenly equaled $15 a month.

By 1996, it was this financial hardship that forced Dr. Mohammed Karim, at that time a professor, to leave Iraq and head for a teaching position in Libya, where he’d relocate his young family of four children a year later. He’d find that he was joined by colleagues fleeing persecution for their communist beliefs; others, he learned, left to the Soviet Union, Europe, or were executed.

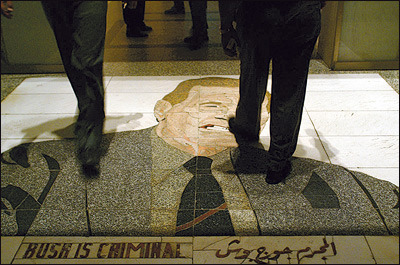

Two pairs of legs, pictured hips-down, walk over a depiction of President George H. W. Bush grimacing above the inscription “Bush Is Criminal,” written in English and Arabic. A reaction to cruel sanctions, war, and residual airstrikes, this floor mosaic was installed at the lobby entrance of the landmark Al Rasheed Hotel after it was hit in a U.S. airstrike in January 1993, according to a Wall Street Journal report. Prominent and respected artist Layla Al-Attar (1942-1993) was killed in subsequent airstrikes and rumors circulated that she had been targeted because of this piece. The piece would be removed in 2003 by American military forces.

Iraqi people continued to resist the sanctions wherever possible. The famous book and publishing center, Al-Mutanabbi Street, became known for its black market of censored materials. Artists like Nuha Al-Radi (1941-2004), made art from scrap in lieu of traditional art materials for her “embargo sculptures.”

In Portrait of Zain Habboo, two painted cans are placed side by side, with crudely drawn faces emerging from their lids. Like her later Embargo sculptures of ca.2000-2003, these pieces and practices symbolized the inner lives of Iraqis as they resisted the compounding censorship by their government and embargos by the West. Although Iraqis felt the ensuing material scarcity, their refusal to cease the consumption and production of art served the creative spirit of Iraq.

Under the guise of destroying weapons of mass destruction, the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, commencing another era of destruction and violence. Despite promises to do so, the invading army failed to protect universities and research institutions along with museums and national archives. Many buildings and campuses were burned and looted. Those that survived became headquarters for various sectarian and pro-occupation militias. Iraq intellectuals and academics became the subordinates of unqualified American officers who interfered in academic business.

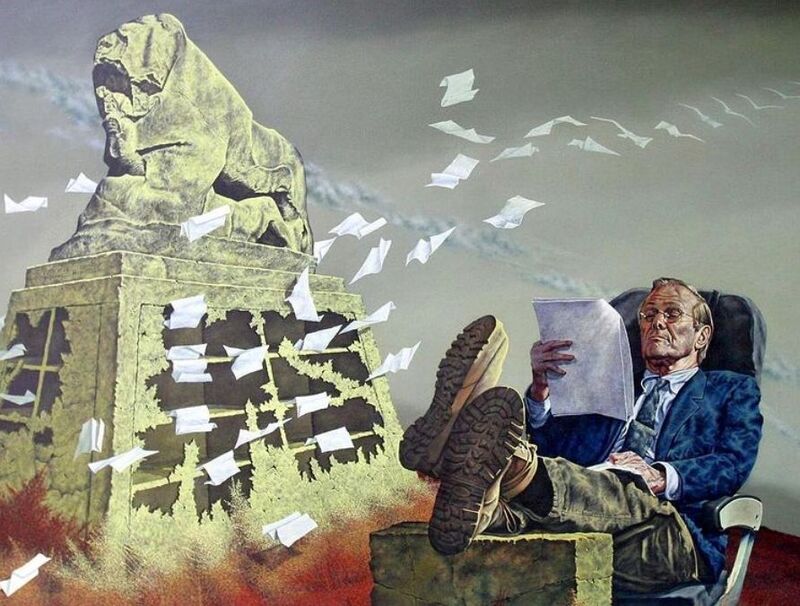

In this painting of the US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld lounges as he reads a newspaper, feet resting upon an Iraqi gravestone. In the background sit the ruins of a Babylonian statue as sheets of paper are blown away in the wind to a distant background. Chemtrails from bomber planes streak the sky; the ground is stained red with the blood of Iraqi civilians.

One canvas of many produced by the artist Muayad Muhsin (1964-) that deeply criticized the US occupation of Iraq, Picnic is directly inspired by a published photo of Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld in an interview where he grossly responded “..stuff happens” to the mass looting of Iraqi museums. This painting provides a scathing response to the neglect and chaos resulting from the invasion: Rumsfeld idly sitting upon dead Iraqis and looking away from the destruction of heritage items.

Renowned artist, Shakir Hassan Al-Said (1925-2004), shaped the artistic practice of a new generation when he refocused their attention on the Mesopotamian past, specifically a collection of artifacts housed in the National Archaeological Museum. Many of the objects were marked or ruined by the passage of time which informed the aesthetic direction of 1980s art. These artists, including Al-Said’s student Hanaa Malallah (1958-), deemed traditional art materials incapable of delivering their artistic message. Instead, they worked with: burnt paper and cloth; barbed wire and bullets; splintered war and found objects, all “borrowing from history and our catastrophic present”, as she explains in her artist’s statement from 2010. For many, this approach — what Malallah would come to conceptualize as her “ruins technique” — became a visual signifier of cultural resistance and a carrier of identity as Iraqi artists. As seen previously in Al-Radi’s “embargo sculptures,” when sanctions continued in the 1990s, it was necessity rather than rebellion that forced artists to use found objects.

This piece by Dr. Malallah is made up of burned canvas, cloth, and cardboard that has been cut, painted, and collaged on a burned wooden board. Like many of her works, it bears her signature grid of triangles which recalls the Islamic ceramic tiles that decorate many ancient walls in Baghdad. “The brown color,” she says in a 2007 Pomegranate Gallery exhibition catalog, “is from burning. It's like the color of my life in Baghdad.” Malallah strongly believes that creativity has survived through the war.

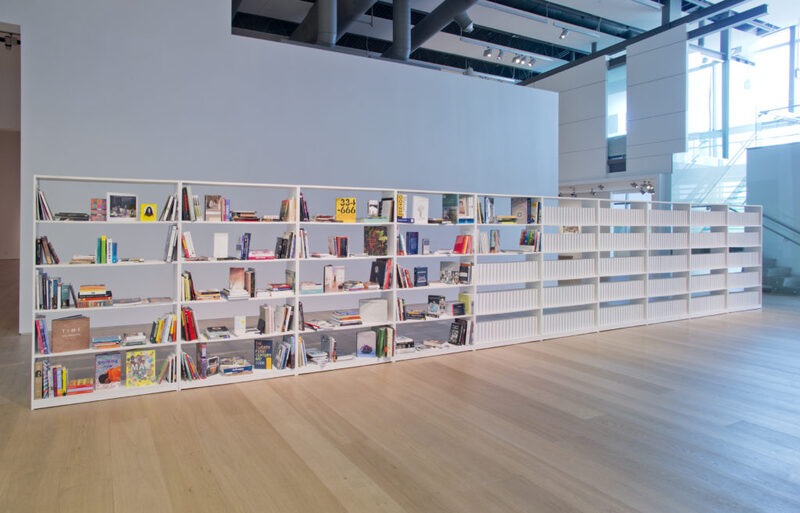

The College of Fine Arts at the University of Baghdad lost their collection of more than 70,000 books in a fire set by looters following the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Even now, students at the college still have few resources from which to study.

In Wafaa Bilal’s (1966-) work 168:01, an installation of an unadorned white library is both a monument to the enormous cultural losses endured throughout Iraqi history and a platform for its hopeful rebirth. The library, composed of a series of white shelves filled with blank volumes, serves to connect its visitors to the College of Fine Arts in Iraq. Intended to restore the collections lost in the destructive wake of the 2003 invasion, 168:01 positions viewers as potential donors invited to contribute funds for the purchase of texts on a faculty member wishlist. As the installation receives donations, the blank tomes are replaced with the purchased books. Donors receive the blank tomes in return for their contribution, and after the exhibition, the donated books are shipped to universities in Iraq to support the process of rebuilding. In its most recent installation in Sharjah in 2020-2021, donated books were offered to the University of Baghdad, the University of Mosul, the University of Babylon, and the National Museum of Iraq. The project symbolizes the will to move forward and the beginning of a global effort to begin anew.

Witness to Political Corruption

Resilience in Exile