Resilience in Exile

Dr. Mohammed Karim arrived in Libya with his family, expecting their return to Iraq would be imminent and joyous. When America declared war against Iraq, a majority of Iraqis celebrated, expecting their country to return to the global market and to resemble the oil nations of the Gulf. The reality of American occupation quickly defeated the trust and optimism of Iraqis, including those who had returned to see this “new” Iraq. Dr. Karim’s brief trip home in 2008 showed him firsthand the assassinations of his former friends and colleagues initiated by the wave of sectarian violence that the American military accidentally facilitated.

He decided to stay in Libya for good, until the Libyan Revolution displaced his family again. He took his family to the Choucha Transit Camp within the Tunisian desert, where they resided for 8 months awaiting acceptance into the refugee programs of Denmark, Norway, Germany, Australia, Austria, and Canada — ultimately denied by all of them. During this time, Karim worked with the Danish Refugee Council who provided him with materials to teach art. Deciding to flee the worsening conditions of the camp, the family secretly left to rent an apartment in the city, although Karim kept returning to the camp to teach.

Here, Karim stands with visitors to an exhibition of his students’ artwork. Colorful paintings and drawings fill the walls and a metal sculpture stands out near the center of the room.

For two and half years, Dr. Karim and his family depleted their savings, unsure where they were headed yet certain that it would not be back to Iraq. In August 2013, a fateful letter arrived from the refugee camp; America had accepted their family for asylum. On January 16, 2014, the family of 6 adults arrived in Dearborn, Michigan. His four children started working at the Ford plant and eventually enrolled in local colleges. Hoping to restore his life in the arts and apply his political experiences, Dr. Karim received an MA in social justice from the former Marygrove College and began volunteering for the Detroit Institute of Arts. He started participating in the local artist community, where he connects with artists of similar background through social media and events, such as the Iraqi American Artists Guild exhibition of August 2019.

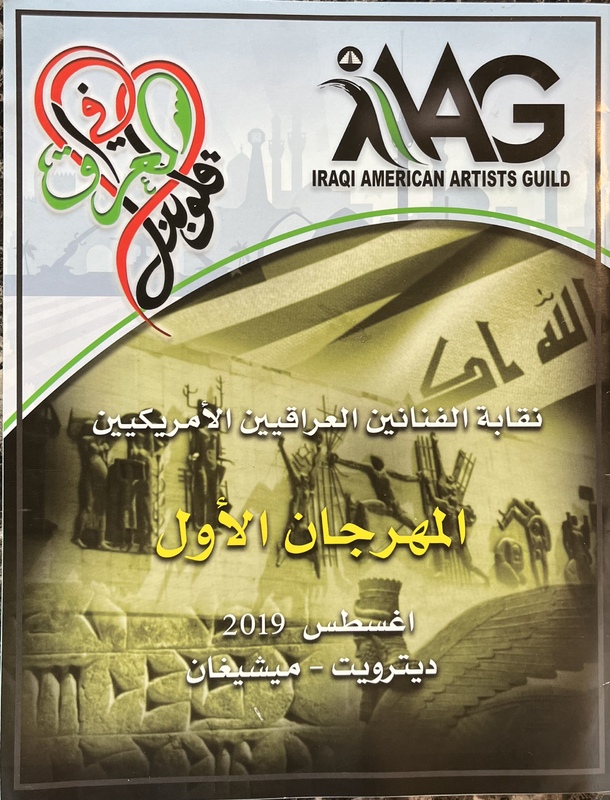

This exhibition brought together many Iraqi artists in the US and Canada. On the cover of the exhibition pamphlet, a calligram in the shape of a heart reads “Our hearts are in Iraq.” The pamphlet, written entirely in Arabic and thus catering to those who were born in Iraq, features photos of artists and imagery of the Iraqi flag, Sumerian art, and scenes of familiar architecture.

The event was funded by the Consul General of the Republic of Iraq in Detroit. The organizers displayed plastic art, screened a movie, read poetry, performed music, and gave speeches. The exhibition was meant to be the first of many festivals held in celebration of Iraqi artists in the North American diaspora before their plans were interrupted by the pandemic. The experience of an exhibition like this brings into stark relief the disparate experiences of Iraqi artists in diaspora. Dr. Mohammed Karim was an active participant in the festival. Other Iraqi artists in the Detroit area participated as well, including the popular Ghaleb al-Mansouri.

In this photograph from the event, Dr. Karim stands with al-Mansouri in front of some of the artwork exhibited. As a newly close friend of Dr. Karim, he supported and enabled his connection to the local Iraqi art community when he moved to metro-Detroit. Each has experienced diaspora and exile differently. Al-Mansouri arrived in the States in 2014 after receiving asylum and performed solo exhibitions for a number of years, before being deported back to Iraq.

Some Iraqi artists from further abroad were able to participate in the Iraqi American Artists Guild exhibition also. The aforementioned Mahoud Ahmed attended as a distinguished guest, as did artist Dr. Saad Al-Tai (1935-).

Though Dr. al-Tai was able to participate in the exhibition, his experience represents another kind of exile. In this image he poses before a large rug reproducing one of his paintings. The composition depicts abstractions of Iraqi architecture with figures in the windows, made from bold streaks of red, yellow, and blue. Al-Tai’s career is long and prominent; already recognized as a great artist by the 1977 Iraq Contemporary Art collection, Al-Tai is of the very few surviving artists who has continued to live in Iraq. His career survived all of Iraq’s political destructions and reincarnations — today, he is considered a national treasure. Although Al-Tai anchored himself to Iraq, there is still an exile to be spoken of when the university and the artist’s community did not remain in Iraq with him. Colleagues, friends, students, and spaces did not follow him through his long and distinguished life.

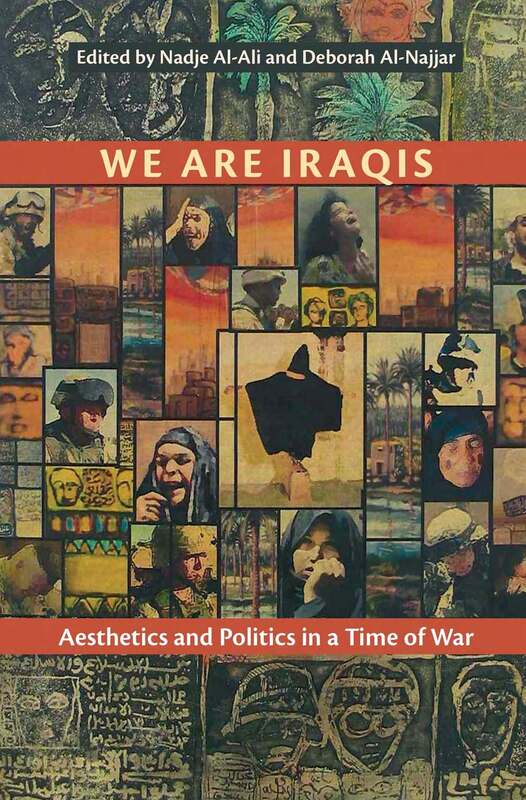

Still other Iraqi artists in diaspora have been prevented from attending US-based exhibitions. The same year as the Iraqi American Artists’ Guild festival, the painter Afifa Aleiby was denied a travel visa to attend a New York exhibition featuring her work, Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011. As reported by ARTNews, several other prominent artists among the 80 with work in the exhibition were also denied visas and thus unable to attend.

Born in Basra in 1952, Aleiby studied at the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad, before leaving Iraq for the Soviet Union in 1974. The political situation in Iraq kept her from returning home, and she lived and worked in Italy, Moscow, and Yemen before settling in the Netherlands.

Aleiby’s pieces reflect her experience of diaspora and exile. Aleiby laments the Iraqi identity that fell with the political upheaval; leaving before the Ba’athi enforced and UN sanctioned isolationism, the following generation of Iraqi refugees embodied a sectarian identity, forwarding their ethnicity and religion instead of their nationality. Aleiby, who belonged to an Iraq propelled by the socialist revolution, does not find solidarity within the Iraqi-European community. Instead, she identifies as a woman artist, as embodied by her portfolio of women in nature. Still, Aleiby occasionally produces pieces reacting to the despair of her homeland which stand in stark contrast to her typical productions.

These paintings, both oil on canvas, are examples of two different facets of Aleiby’s work. In The Rape of Baghdad, she reflects on the destruction caused by the war and occupation, focusing on the violence faced by women. A mother holds her daughter as tanks roll through the background, the colors of the American flag bright against the surrounding destruction. The painting makes one think that the mother has experienced many cycles of destruction, has become accustomed to seeing her country in pain, while her daughter is perhaps facing it all for the first time.

In the second painting, The Window, a woman in a red dress holds a child. She stands in front of a window out of which we can see a garden and a large structure. The colors are bright but the expressions on the face of the mother and the child are somewhere between neutral and grim. We can assume that this is a depiction of a woman in Europe. The emphasis on women is a notable shared trait of these two very different works.

Political Retribution and Sanctions

Art as Resistance