Parodies of Fashion in Print, 1818–1846

Prints have been used, since the birth of the medium, to disseminate irreverent political and social commentary. As an extension of the observation of social mores, it is no surprise that fashion was targeted by caricaturists. The caricatures highlighted fashion absurdities but sometimes also reached into moral and social anxieties. A close relationship between fashion plates and caricatures was established in both London and Paris, as they were centers of fashion and of the printed press. The detailed observation of current dress and manners are skills that were necessary to caricaturists and print designers alike. The prints often were a product of the same market, executed by the same designers and printmakers, issued by the same publishers and consumed by the same audience.

The humor depicted was not necessarily always about clothes or accessories but could be very revealing of social customs: what trends made people laugh at a particular moment in time? The topics under comical attention were often expressed in gendered terms. For instance, there was a fear that women would deceive men with their clothing and accessories, as shown in the surprised men kissing women through their large bonnets in Le Suprême Bon-Ton (The Supreme Bon-Ton, 1810–1815).

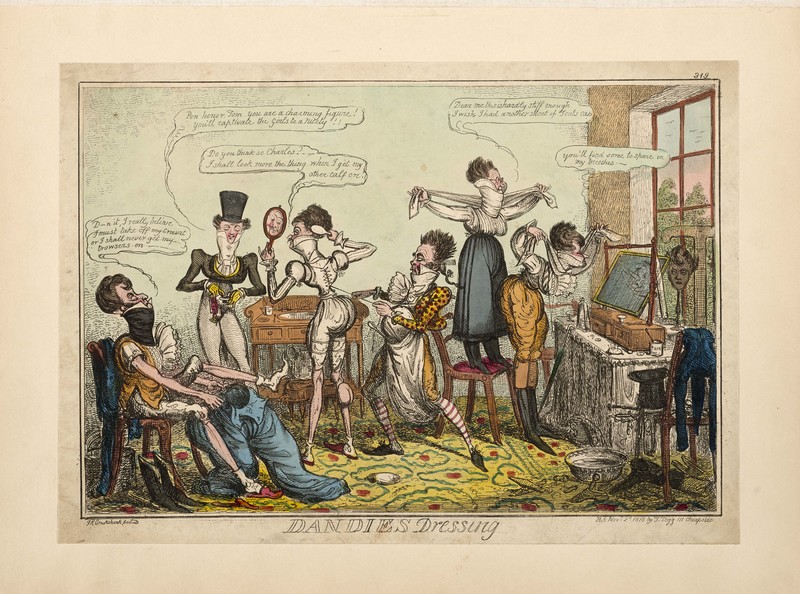

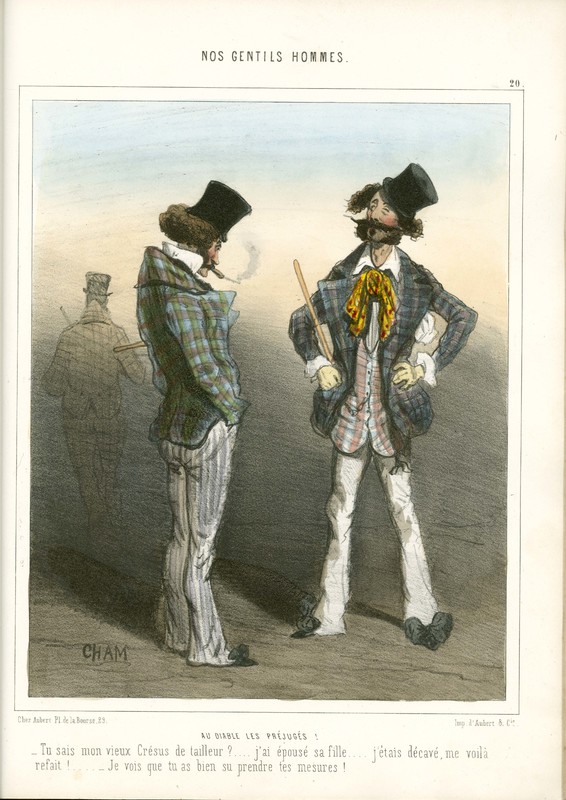

In other instances, the humor is less straightforward. If women were often held responsible for depleting their family’s fortune to keep up with fashion, that tendency is inverted in the case of the caricature from Nos Gentils Hommes (Our Tasteful Gentlemen, 1846) where the man is the one accused of prodigality. In the print of the “Dandies Dressing” from Dandies (1818), expected gender norms are disrupted: the male body is feminized, and their gestures could be characterized as effeminate. [IG]

The dandies, a group of clothes-conscious men, led male fashion during the Regency period (1811–1820) in England. In this print, none of the six dandies seem to be wearing clothes that fit. Consider the man in the lower left, complaining that he cannot get his oversized pants on unless he takes his cravat off. The third man from the left is wearing a bulging prosthetic calf while having his waist cinched. These satirical depictions point to the temporary body alterations dandies would endure, exaggerating their appearance with accessories and props to meet beauty standards.

The artist Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856) mocks the dandies’ narcissism and their insecurities: the figures all seek affirmation from one another (one asks, “Do you think so Charles?”) and use mirrors to examine their appearance. As extreme and flamboyant as the dandies appear, however, Cruikshank also invites us to consider how the clothed body is never quite natural. Instead, it is always shaped and codified by social pressure. Our responses to those social pressures can be subtle or extravagant. [IG]

Although fashion was largely a topic discussed in women’s magazines, both genders were affected by trends and pressure to stay in fashion. In this lithograph, the men’s bushy mustaches, impressive sideburns, and oversized bows are purposefully ridiculous. After the French Revolution, a newly established social order witnessed the rise of a slice of society called the nouveaux riches, or “new money.” The words jeunesse dorée (gilded youth) in the title of this book refer to this group of privileged socialites. Throughout the plates, the artist Cham (Charles Amédée de Noé, 1818–1879) pokes fun at men’s vanity, but the situation’s humor is complicated by the interplay of image and caption. Titled "Au diable les préjugés" (To hell with prejudices), two men engage in conversation. One says, “you know my old Cresus of a tailor? I married his daughter… I was ruined, but I’ve bounced back…” The other replies “you see, you were well able to take your measurements.” The punchline is a play on words that conflates sartorial measurements and life measures, satirizing the lengths to which men would go in order to keep their fashion up to date. [IG]

The plate’s title, Le Baiser Perfide, could be translated as “The perfidious or deceitful kiss.” The image humorously depicts the ways fashion can lead to deception in amorous enterprises. As one man’s hair gets caught in a woman’s funnel-like hat, the other man gets spooked by what he sees inside a second woman’s similarly cavernous bonnet. The book’s plates offer a glimpse of what was made fun of during this period, namely the outlandish ensembles worn by the ‘incroyables’ and ‘merveilleuses.’ The French hats, similar to Regency poke bonnets, were called the ‘invisible’ because the hat’s deep peak shielded the wearer’s face from view. In this case, the hats are ridiculously enlarged; a properly sized example can be seen in a fashion plate from the Journal des Dames et des Modes reproduced below. The publisher, Aaron Martinet (1762–1841), was one of the first to display prints on his shop’s windows as a means to attract potential buyers. [IG]

Expanding the Fashion Journal, 1809–1878

Historical Costumes and Historicized Clothing