Expanding the Fashion Journal, 1809–1878

Technological and commercial changes affected the representation of clothing in fashion journals, while also indicating how such representations illustrate divisions between Britain and France, men and women, and people from different economic classes.

Ready-to-wear clothing only became widely available in the late nineteenth century. Before this time, seamstresses and tailors made most clothing, if one did not make it at home. Shopping for textiles was therefore more common than shopping for full garments as one typically does today. For this reason, textiles were important registers of changing fashions. Fashionable textiles had also factored centrally in European industrialization, as foreign fabrics imported by the European East India Companies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had inspired domestic imitations. Britain took the earliest lead in innovative production, and the cotton spinning, weaving, and calico printing factories of Manchester set the standards for mass production and cheapness. Few fashion journals mention that this phenomenal expansion of access to clothing materials had been made possible by the labor of enslaved people across the Atlantic and poorly paid European factory workers.

New technologies also led to dramatic changes in publishing during the nineteenth century. The new printmaking medium of lithography greatly increased the speed with which images could be created and reproduced, while the medium of wood-engraving allowed images to be set alongside moveable type. The process of “stereotyping” made identical printing plates available to multiple publishers in different geographic locations. Taxes on printed material were being drastically reduced, and paper became cheaper with the switch from using rags in papermaking to using wood pulp. As a result of these changes, heavily illustrated fashion journals could be priced to appeal to a widespread middle-class (and increasingly female-dominated) audience. [CW]

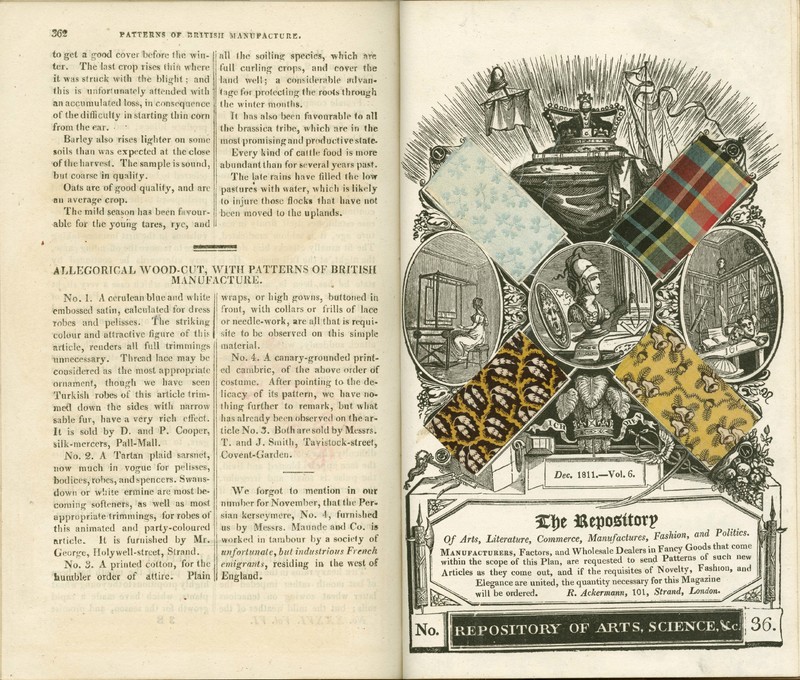

The inclusion of actual fabric samples in this general interest journal was complemented by textual descriptions of new fashions and visual information provided by fashion plates. This tactile feature, however, offered a far more exact understanding of the newest fabrics than engravings or text could. Thinly-disguised advertising for cloth merchants probably supported the added cost of including the fabrics. The textile samples shown here addressed a range of budgets and tastes, from the “striking” satin and “party-coloured” Tartan plaid pasted in the top spots of the framing woodcut, to the “humbler” printed cotton fabrics occupying the lower spaces.

Like the Gallery of Fashion (also on display), the Repository of Arts was helmed by a German immigrant, Rudolph Ackermann (1764-1834), who proudly broadcast his loyalty to England, his adopted country. Because textiles were key drivers of the British economy, fashion constituted a significant economic battle site in the wars against France. These international conflicts were a constant undercurrent in fashion journals at the time; for example, the text shown here notes the presence of French refugees working in the British textile trade. This reminder of the cruel human toll of France’s Revolutionary violence points to Britain’s view of itself as a commercially thriving place of refuge, while also reinforcing the facing textile feature’s privileging of British-made fashionable goods. [CW]

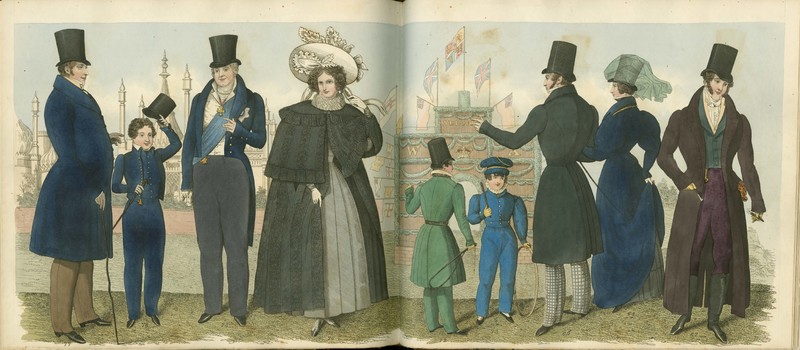

British tailors dominated the creation of men’s fashions throughout the nineteenth century. Self-promotion was paramount in establishing oneself in the tailoring trade, and publishing fashion journals became a popular strategy for claiming preeminence. The London-based tailor George Walker [life dates unknown] innovated this genre by commissioning elaborate lithographic illustrations, including pattern sheets touting his supposedly unique scaling system, and offering readers actual samples of the newest fabrics stocked in his shop. Tailors working outside London comprised the journal’s primary subscribers, and they likely displayed the Cyclopedia in their shops.

The illustrations in Walker’s Cyclopedia often utilize unmistakably British settings, much like the Gallery of Fashion. This double-page spread is set in Brighton. The recently completed Royal Pavilion peeks out on the left; its brazenly orientalist mixture of Indian and Chinese architectural components aligns with the borrowing from foreign cultures that also inspired fashions for European dress. A triumphal arch rises on the right side of the spread, celebrating the arrival of the royal family. The accompanying text identifies the people in the scene as the royal family. This image implies that Walker enjoyed the highest levels of patronage, but his creations were more likely worn by the upwardly mobile gentry and bourgeoisie. The bourgeois class’s ties to industry and finance rendered them increasingly powerful in both Britain and France during this period. Fashion, however, continued to take its stylistic cues primarily from the elite. [CW]

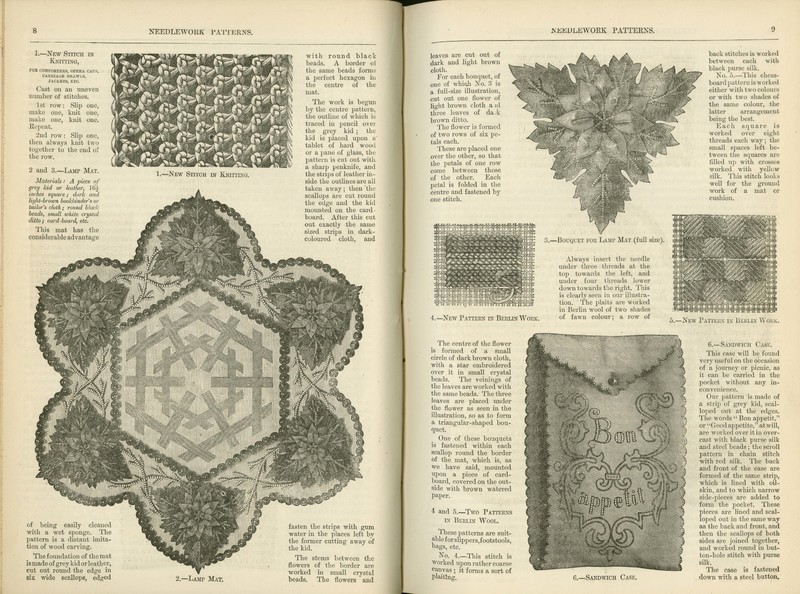

A woman with the skills, time, and energy could re-create fashionable clothing affordably by substituting inexpensive fabrics and utilizing her own labor. The availability of the sewing machine by the 1850s made dressmaking at home even easier. Many fashion journals catered to home sewers by offering more than just the visual inspiration of fashion plates. This 1867 spread from The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine gives detailed visual information about new needlework techniques. The medium of wood-engraving allowed the instructional images to be interspersed within the corresponding text, rather than printed separately.

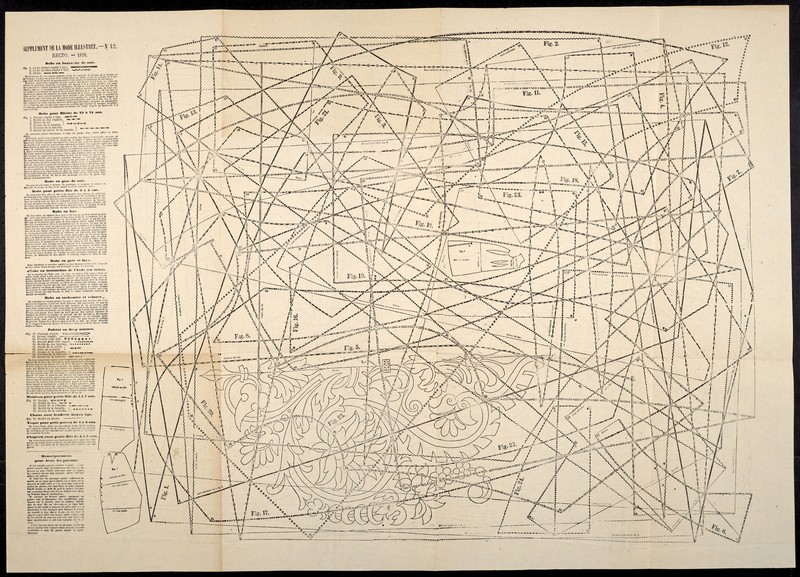

The sewing pattern sheet displayed in the top of this case guided the creation of full garments. Because these fragile sheets were often used in pattern-making, they rarely survive. This pattern sheet was created using the medium of lithography. By placing multiple patterns on top of one another, with each demarcated by a different type of line, the journal maximized the available space on the printing stone and thus reduced the cost of production by only using one sheet for a number of garments. Instructions for piecing the forms together are included on the side of the sheet. This text regularly refers to the finished garments shown in the issue’s fashion plates, suggesting that the images in fashion plates were not merely fantasies, but could also function as practical aspects of actual fashion production. [CW]

Godey’s Lady’s Book was one of the most successful early American fashion journals modeled on European counterparts. Unique among early fashion journals, it was directed by a female “editress,” Sarah Hale, from 1836 onward, rather than a male editor. Her example paved the way for women to pursue careers not just as fashion columnists but also as influential leaders in journalism more broadly.

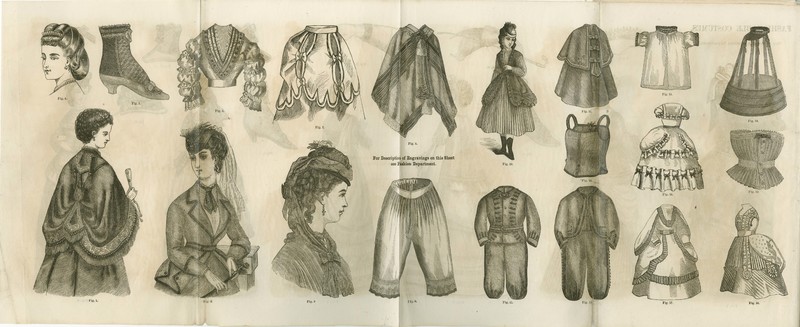

The wide range of goods shown in this “extension sheet” (a supplement to more conventional hand-colored fashion plates) seems to create a virtual analogue to window shopping. The text accompanying the plate even advertises an early precursor to online custom shopping services, and reveals the degree to which fashion journals actively participated in expanding the geography of commercial consumption:

“Having frequent applications for the purchase of jewelry, millinery, etc., by ladies living at a distance, the Editress of the Fashion Department will hereafter execute commissions for any who may desire it, with the charge of a small percentage for the time and research required. . . . Instructions to be as minute as possible, accompanied by a note of the height, complexion, and general style of the person, on which much depends in choice.”

The subscription information in Godey’s indicates a growing culture of female sociability built around journals: while a single year’s subscription cost $3.00, special deals were available for providing up to eleven copies to “clubs,” where women could perhaps sew collectively or discuss which of the pictured items they wanted to seek out on their next trip to a large city. [CW]

The Growth of Fashion Publishing, 1785–1815

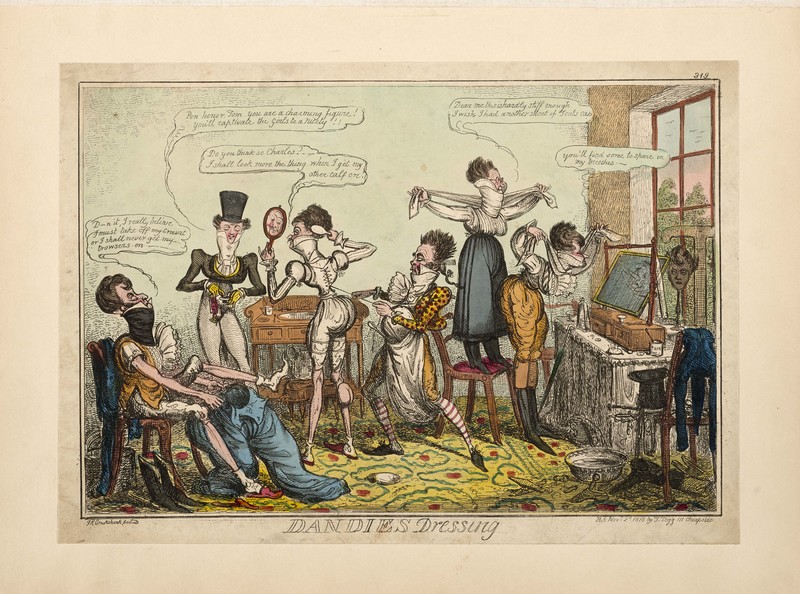

Parodies of Fashion in Print, 1818–1846