Beyond Valmiki

Bali

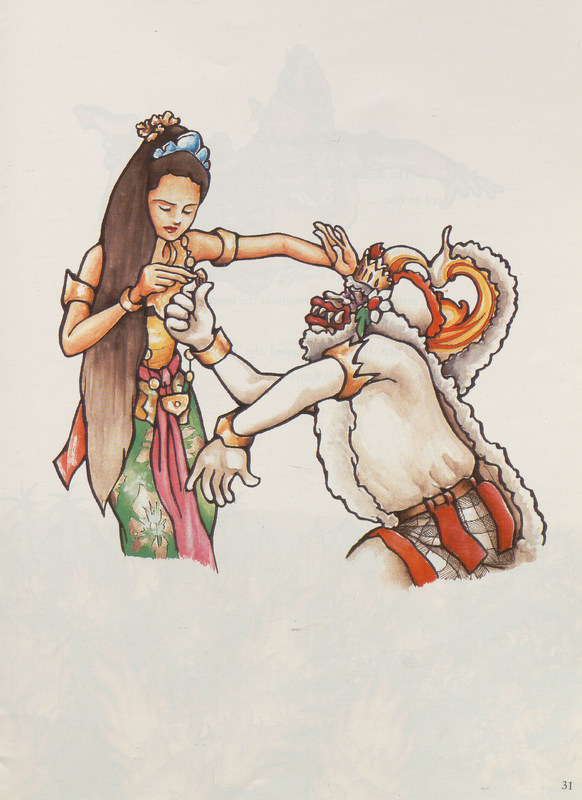

The illustration below comes from a Balinese kecak book. Kecak is a style of Balinese dance and drama that tells the story of the Ramayana. Rhythmic chants and dances have long been a part of Balinese tradition, but kecak is a newer addition. The dance, which is typically performed by men, was developed in the 1930s by German expatriat and artist Walter Spies.

As for the story, it is very similar to the Valmiki version, with a few exceptions. As expected, several of the spellings are different — Hanuman becomes Hanoman, Lanka becomes Langka, Ravana becomes Rawana. A plot difference involves the heroism of a supporting character. In the Valmiki Ramayana, Jatayus is a noble vulture who tries to stop Sita from being kidnapped by Ravana. He flies after Ravana's chariot and attacks the evil rakshasa, but is badly injured. Moments before his last breath, Jatayu tells Rama and Lakshmana what happened, allowing them to better prepare to rescue Sita.

In the Balinese version, Jatayu still yets a moment of heroism, but it occurs at a different point in the epic. When Rama and Laksmana are on their way to Langka, a son of Rawana attacks them, trapping them inside the coils of a gargantuan serpent. Jatayu comes to the rescue by pecking the serpent, allowing the brothers to escape unharmed.

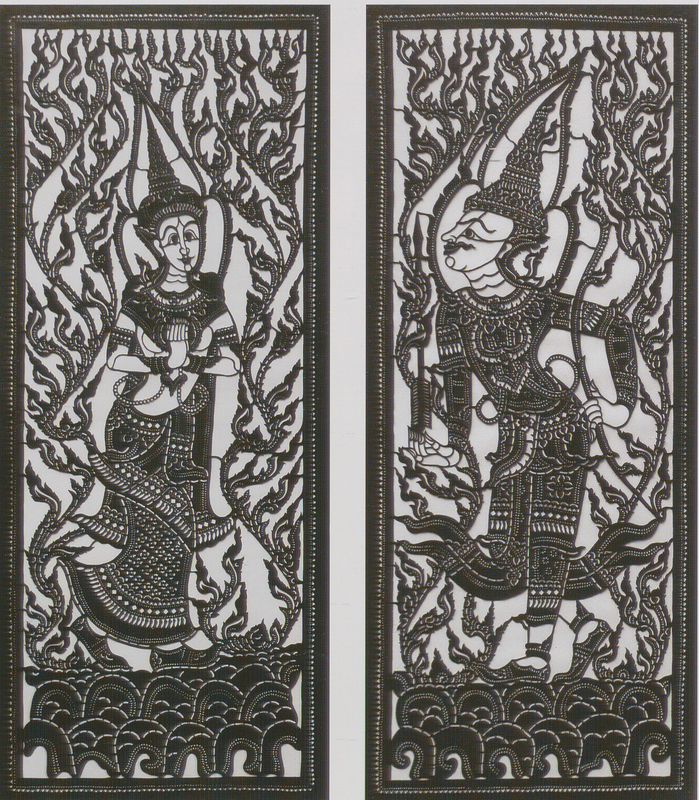

Malaysia

Just like Valmiki's version, the Hikayat Seri Rama gained popularity through both written and oral tradition. In Malaysia, puppetry is another popular way to tell the epic. The image below is an example of wayang kulit siam — traditional leather puppetry. Wayang kulit siam puppets are two-dimensional and intricately carved with fierce expressions and ornate decorations. Besides the puppets' dialogue, there is a narrator who gives commentary and an orchestra with drums, cymbals, and gongs.

Interesting, Seri Rama is not portrayed as favorably in the Malaysian version. While Valmiki holds Rama up as a true hero and an ideal man, Malaysian storytellers are more likely to emphasize his weaknesses, such as arrogance and vanity. This makes Rama seem more human, which audiences in Malaysia connected to. Brother Lakshmana is given a greater role in the Hikayat Seri Rama, and Ravana is appreciated as a noble, dynamic character. Hanuman's character also changes; rather than being celibate, the monkey warrior has a lover.

Another notable difference between Valmiki and the Hikayat Seri Rama is in the nature of Kaikeyi's boon. In Valmiki, Kaikeyi is given two boons when she saves King Dasaratha's life. Alternatively, in the Hikayat Seri Rama, Kaikeyi is explicitly told that her son will be king, and she is given an extra boon. This makes her palace ambitions more understandable.

Thailand

The Ramakien, as the Ramayana is known in Thailand, is the country's national epic. Though the story has been told for hundreds of years, the earliest versions have been lost, so the retelling by King Rama I is the one most commonly studied. Rama I changed his name to match that of the legendary hero when he ascended to the throne in 1782. To this day, Rama is an extremely popular name for South and Southeast Asian men.

Widespread affection for the Ramakien has led to incredible artwork. Below is a mural from the Wat Phra Kaew, or the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. The temple was constructed under the reign of Rama I, who wanted the sared twenty-six-inch jade figure of the Buddha to be surrounded by the great Hindu epic. This cultural blending was not unusual for the region, and even long after Rama I's passing, the murals have continued to be restored.

As for the story itself, the central goal of rescuing Sita from Ravana remains the same, but there are some deviations from the Valmiki. Like in the Mayalsian version, Hanuman is not celibate; the monkey has a child with Nang Supranamajcha, a half-woman, half-fish daughter of Ravana. The story of Sita's banishment near the end of the epic is also markedly different than the Valmiki Ramayana. While Valmiki explained that there was too much gossip about Sita's supposed infidelity for Rama to keep her in the palace, King Rama I writes that a rakshasa, bitter about Ravana's defeat, tricks Sita into drawing a picture of Ravana and leaving it under Rama's bed. This makes Rama believe that Sita misses Ravana.

Divine Power

About the Exhibit