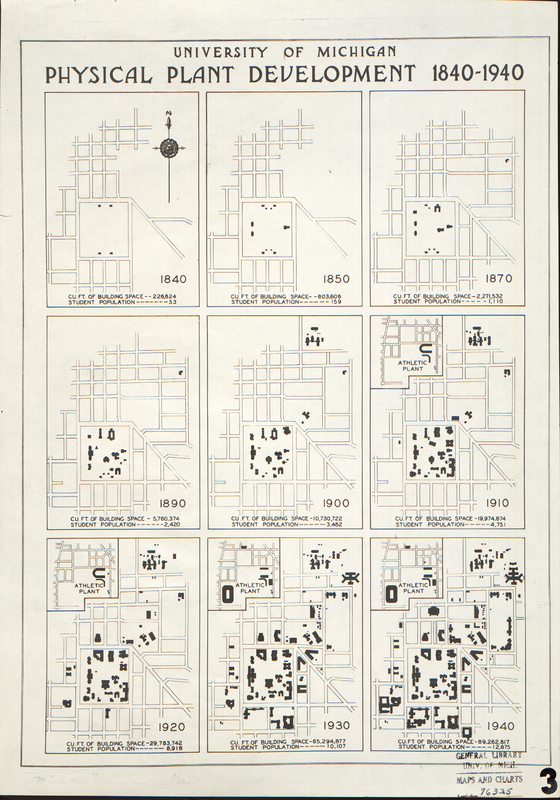

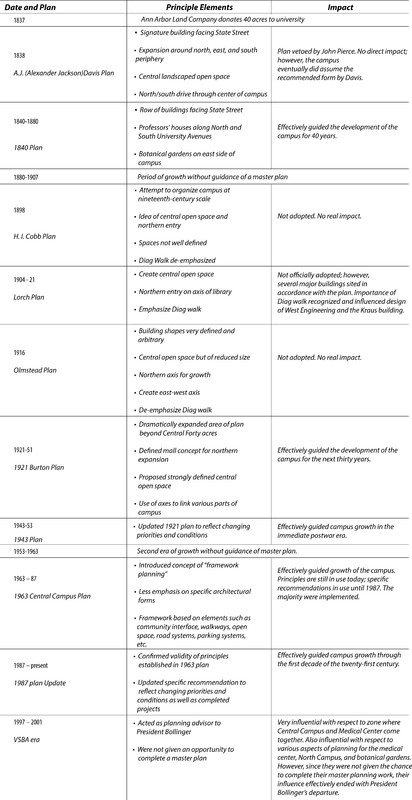

Growing the Campus: 1850s - 1869

Much like for the rest of the country, the Civil War marked an important turning point in the university’s history and the development of campus. While the 1840 plan continued to guide campus planning over the next two decades, its influence became increasingly amorphous. At the same time, the visual continuity of campus slowly began to crumble as the architectural styles across campus continued to evolve. Alexander Jackson Davis’s original design featured the Gothic Revival style, which was abandoned by the 1840 plan, in favor of other classical styles, including Greek Revival and Italianate and Carpenter Gothic (Mayer, 59-60).

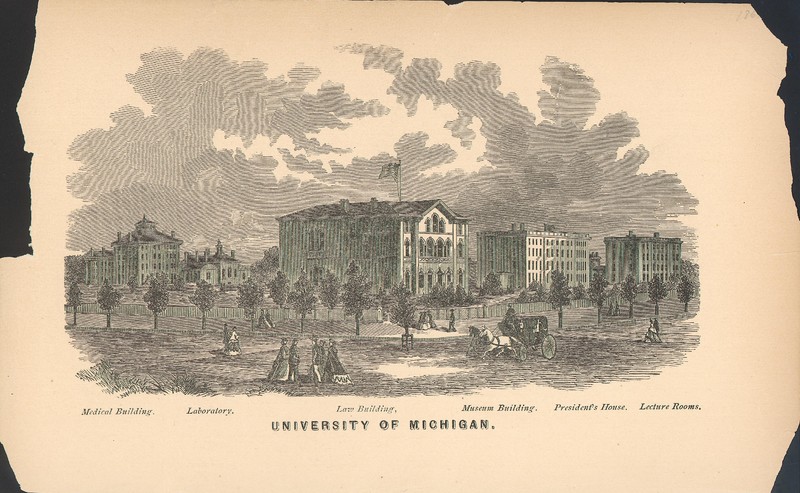

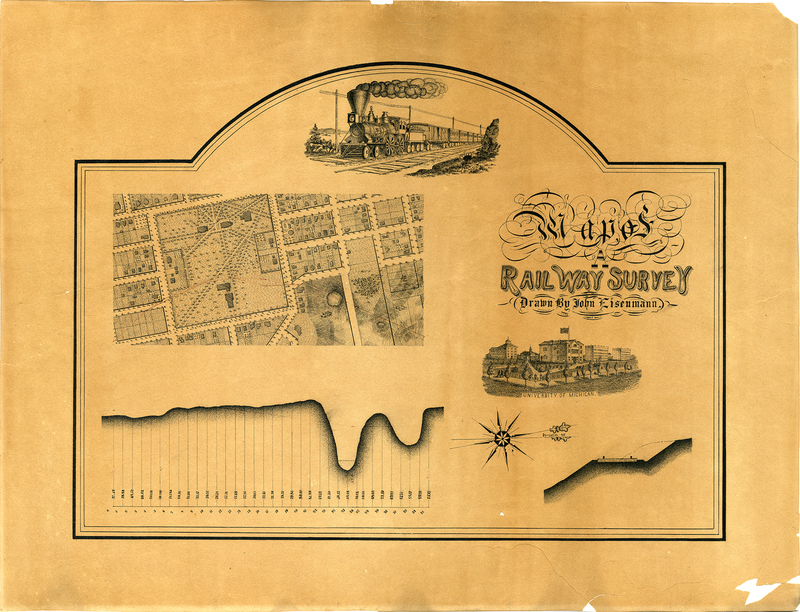

Similarly, the arrival of President Tappan in 1852 marked a stark change in direction for the growing school. Henry Tappan wanted the university to become one of the first and foremost research institutions in the country, with an emphasis on research and applied sciences. President Tappan was an advocate of the German style of university, believing strongly in the research component (Mayer, 28). In line with this vision, the majority of the buildings constructed during Tappan’s tenure were scientific in nature, including the Medical Building (1850), the Detroit Observatory (1854), and the Chemical laboratory (1856).

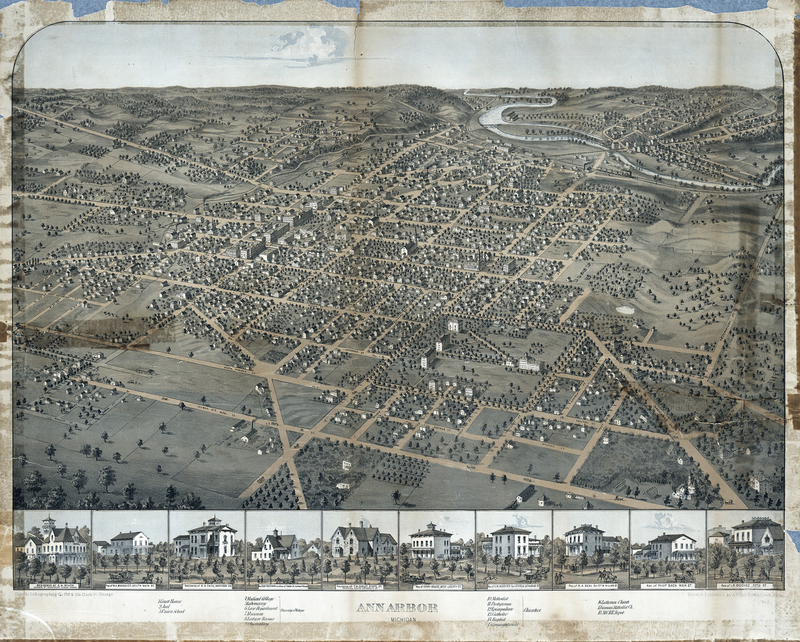

Prior to the Civil War, the University of Michigan campus resembled the many other small liberal-arts campuses that spread across the country, small and classical in style. However, the war marked a stark change in universities throughout the young country. Instead, there came a shift towards larger universities, modeled after the German style of university, focused on graduate and professional education and research (Mayer, 58). Immediately following the war, the campus remained much as it had, but the ensuing decades brought drastic and unguided growth.

1870s-1890s

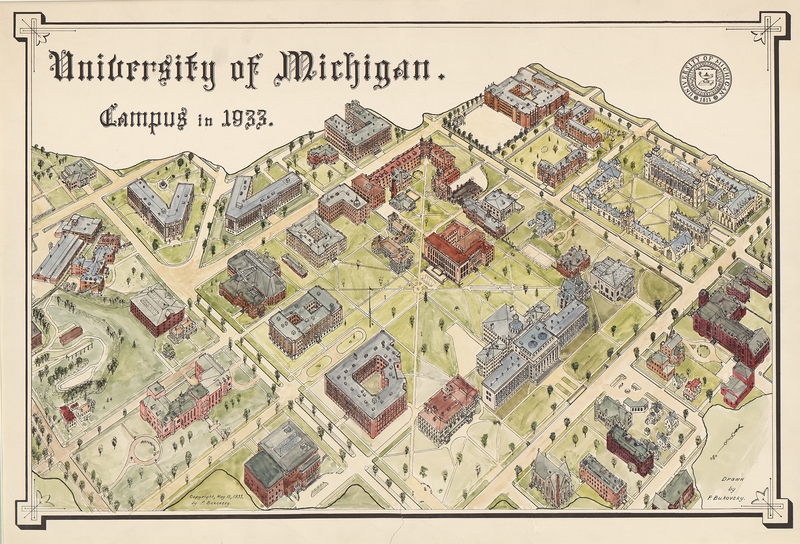

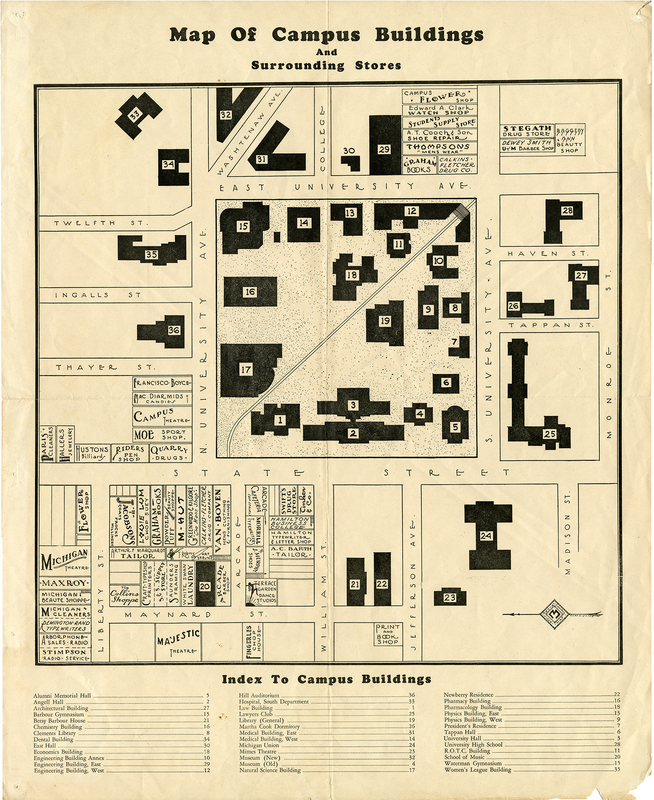

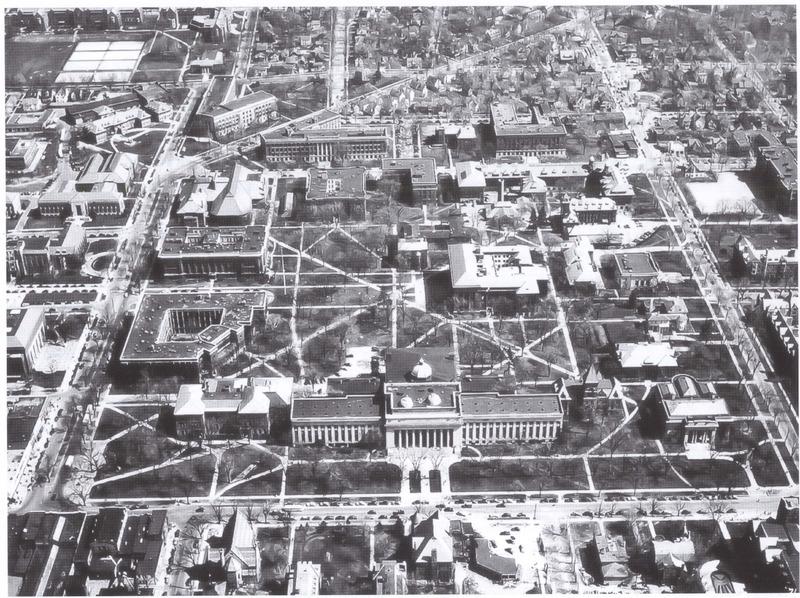

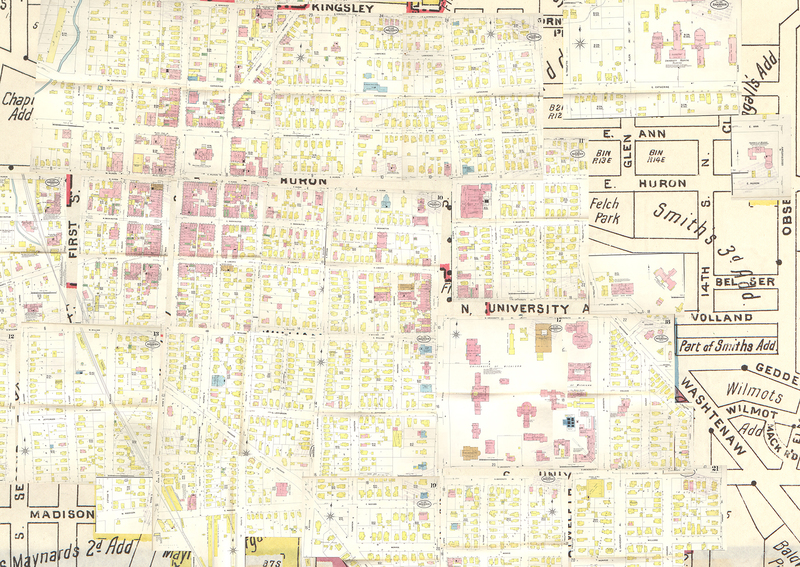

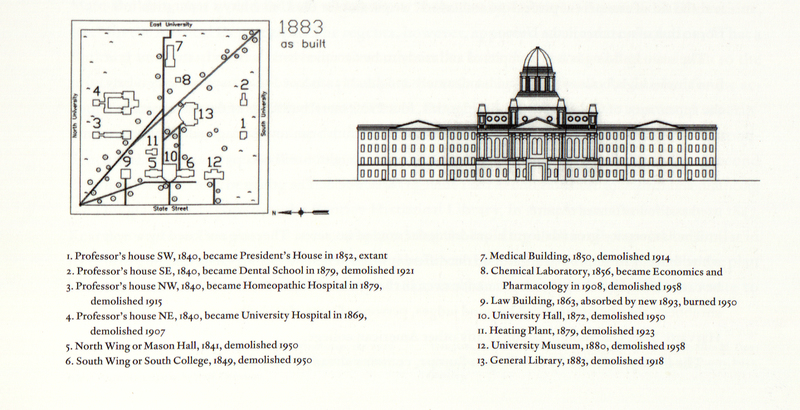

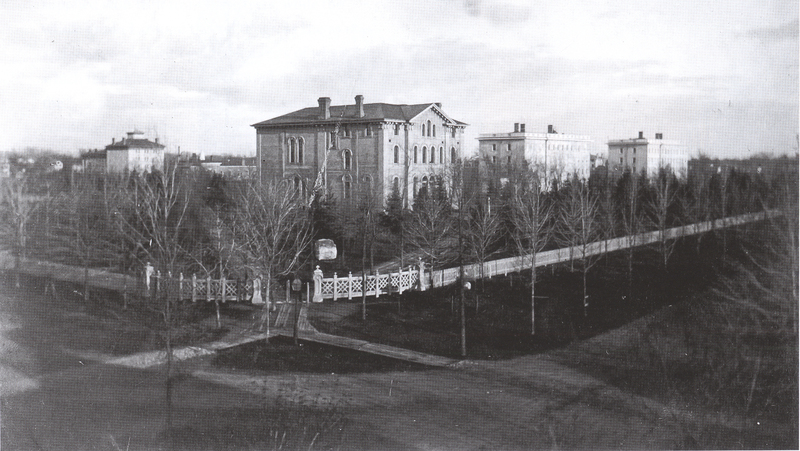

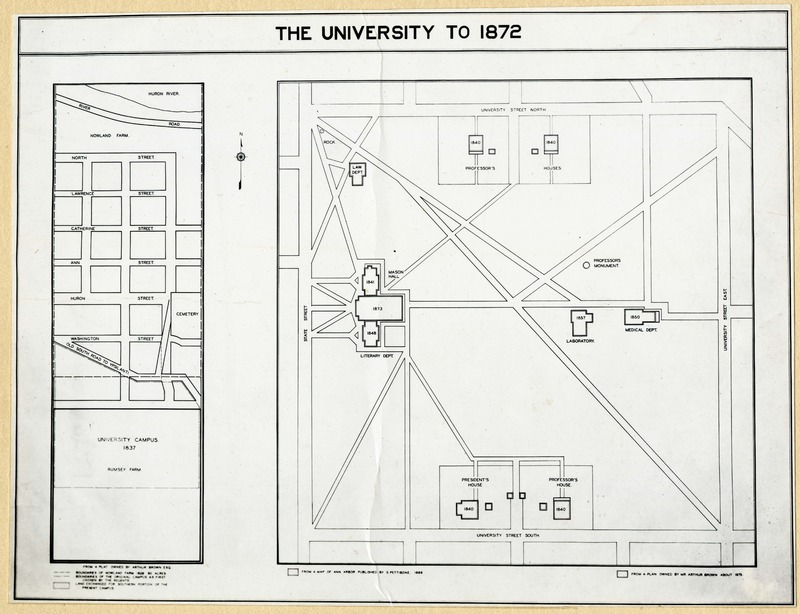

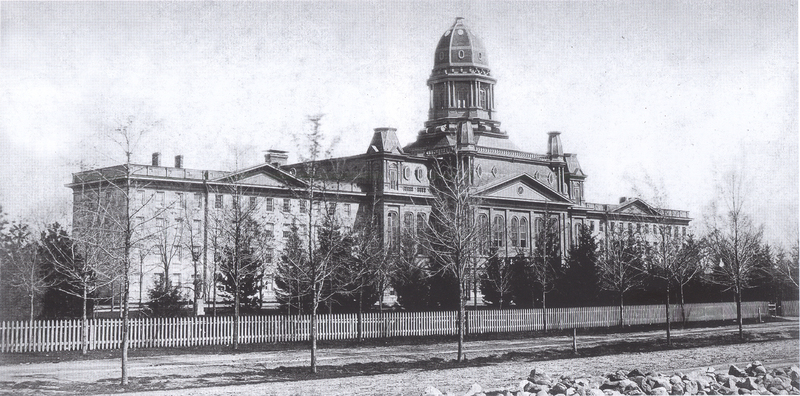

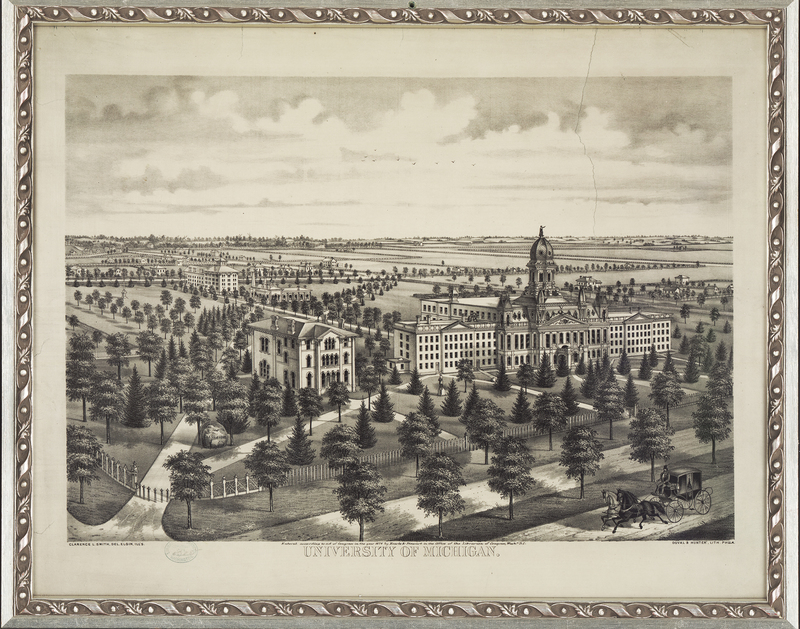

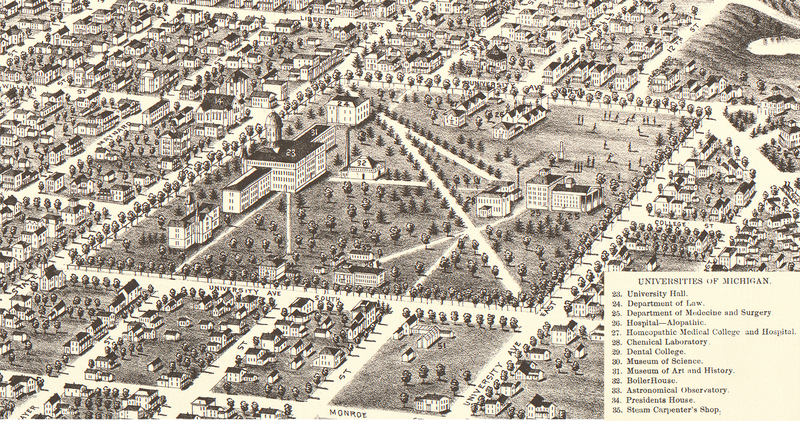

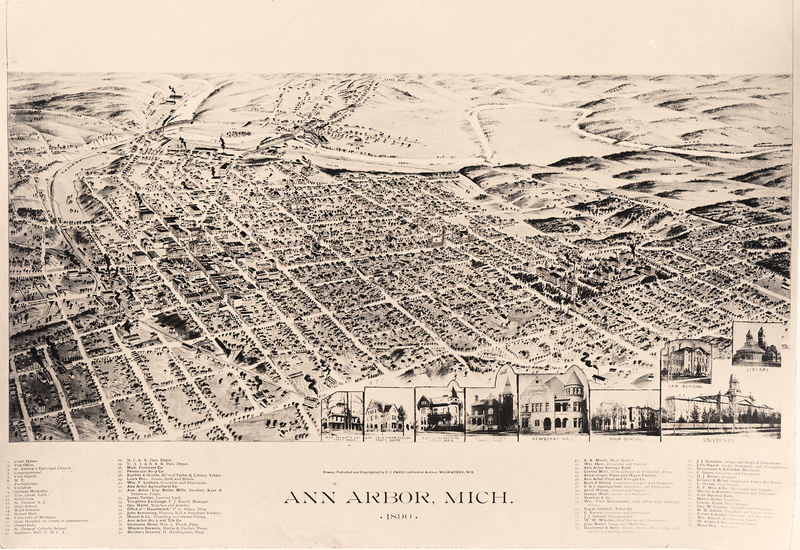

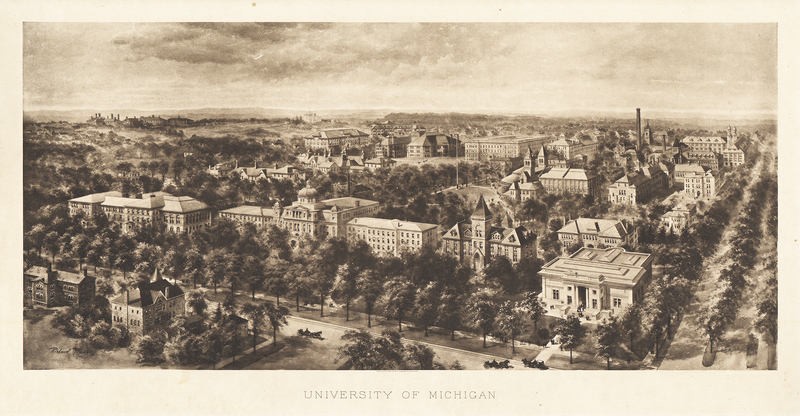

From the 1870s to the 1890s the University of Michigan campus underwent exceptional growth, far surpassing the anticipated needs of the university prior to the Civil War. Enrollment rose rapidly following the war and the university quickly outgrew the confines of the 1840 plan, growing from a small liberal arts college into a large Victorian Campus. Space was needed for growth, but the university was expanding so quickly there wasn’t time to build new facilities. Instead, existing buildings were co-opted and converted for academic use, including three of the original four professors’ houses (Mayer, 61). The only building constructed during the 1870s was the new University Hall, which was built in 1872. University Hall, in conjunction with the Law Building, later renamed Haven Hall, and South College, established the strong State Street row proposed by Alexander Jackson Davis in his original plan for campus. The latter half of the 1870s was a period of mainly remodeling and repurposing facilities on campus.

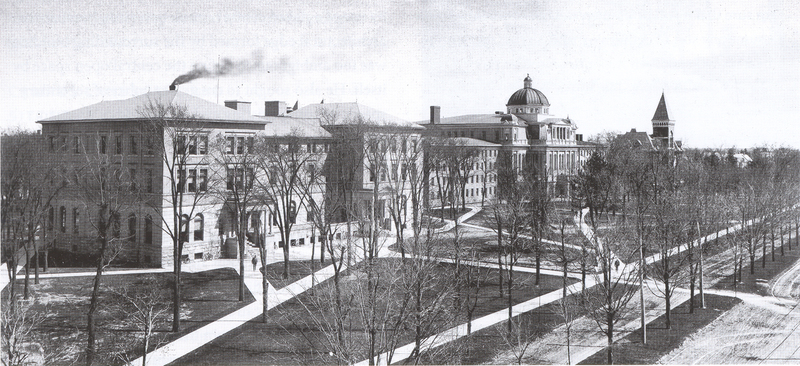

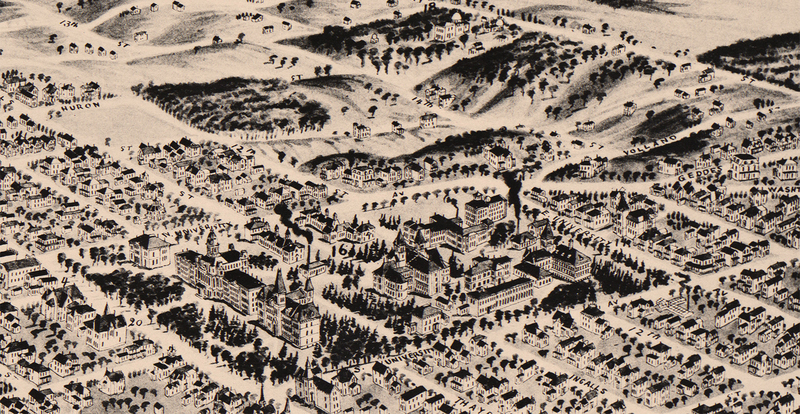

Unlike the recycling of the previous decade, the 1880s were a period of new construction and rapid expansion on campus. It was during this decade, as well, that the 1840 plan’s influence on campus growth officially ended. Emphasis shifted away from the State Street row, instead focusing inward towards the Diag and the academic heart of campus, the new General Library (1883). During this time additional architectural styles were added to campus, further disrupting the visual cohesion and plan of campus. During the 1880s seven of the buildings added to campus were built in the Romanesque Revival style, including the University Museum (1880), the General Library (1883), West Physics (1889) and Tappan Hall (1894). Whereas, as recently as the previous decade, the Carpenter Gothic style had been utilized in the construction of the Pavillion Hospital (1876) and the College of Dental Surgery (1879) (Mayer, 61).

One factor that had profound impact on the development of campus throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century was the appointment of James Burrill Angell as president in 1871. President Angell did not believe in the visual importance of campus or the “bricks and mortar” of a university. Instead, he believed that more emphasis should be placed on enriching the school through its professors and academic leadership. As such, the role of campus planning fell to others during his tenure (Mayer, 60).

Growing without a plan

Throughout the country, the second half of the nineteenth century was a period of “growth, creativity, dynamism, and increasing sophistication, but it was also a period of rough-and-tumble opportunism - the heyday of laissez-faire, every-man-for-himself capitalism and the great age of the individual” (Mayer, 58-59). City planning fell out of favor, with momentary needs outweighing guidance from existing plans. As cities that had outgrown their old plans discarded them and began building, buildings were constructed without consideration of a larger plan or concept for the city. Vistas were destroyed and parks were turned into construction sites (Mayer, 59). Similarly, these national trends played out on the campus level as well.

At the University of Michigan, the importance of campus planning had fallen from favor as well. President Angell chose to focus on enriching the university academically and disregarded any plans for campus development. By the 1880s the original plan for the development of campus had been discarded and the focus shifted inward towards the Diag and the heart of campus. While there were no plans guiding the growth of campus during this time, there were those on campus who saw the importance of such plans and carefully considered the siting of new buildings. In fact, with no plan to guide them, the placement of new buildings was done pragmatically, accounting for the requirements of the facility and any academic relationships to other buildings. The General Library was placed at the heart of the original forty-acre campus, new engineering and medical facilities were added close to the Engineering College and old Medical School, respectively (Mayer, 65-66). One disadvantage of this period of rapid growth was the varying architectural styles utilized. The architectural diversity of campus meant that it would be impossible to embrace one singular style for the design of campus.

It would not be until the Columbian Exposition in 1893 before planning resumed its previous prestige within the nation’s collective consciousness. The world’s fair reminded people of the benefits of a planned environment and launched the City Beautiful movement across the country and across college campuses (Mayer, 59).

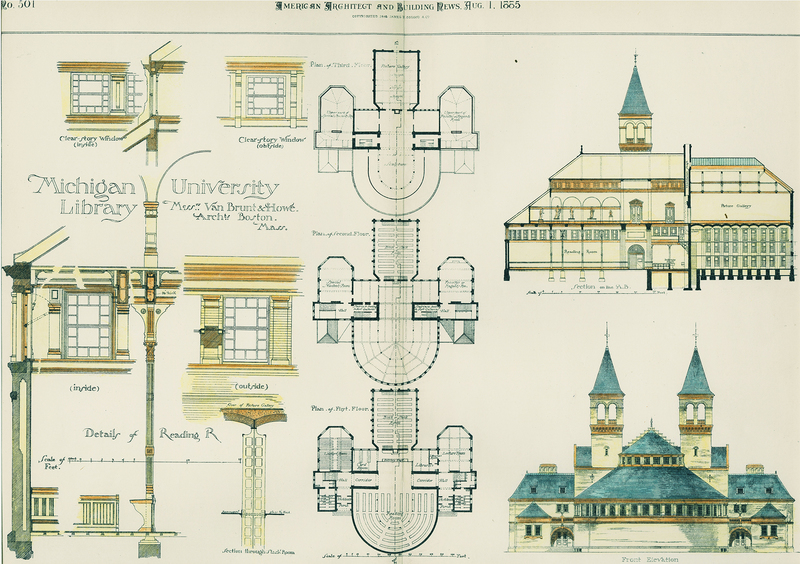

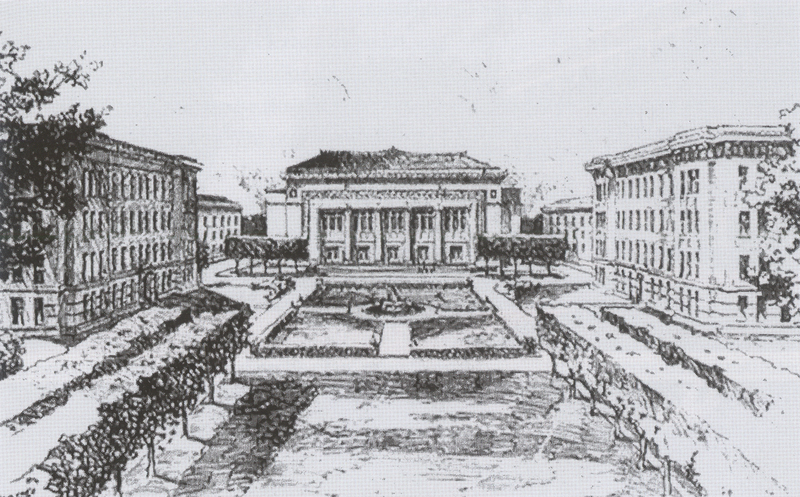

The Library

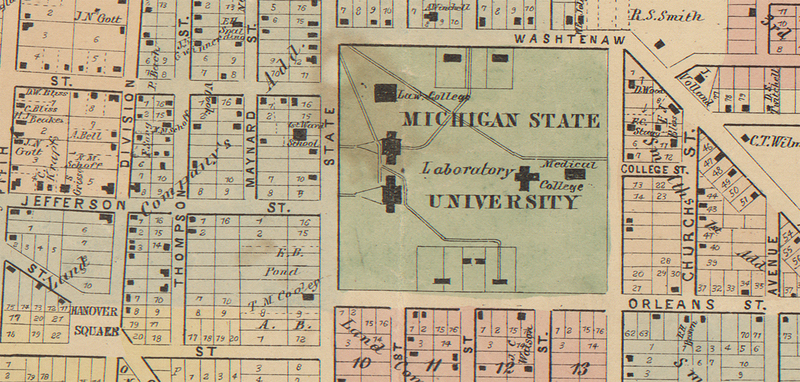

As the university continued to grow throughout the nineteenth century, so to did the university’s need for a general library. Leading up to this point, the library’s holdings had been housed in Haven Hall and the Law School, until funding could be approved for a new building. After much debate over the siting and a competition to select the architects, the architectural firm Ware and Van Brunt won the commission. In 1883 the General Library was built in the Romanesque Revival style at the center of campus. The placement of the library at the heart of the original forty acres was the first derivation from the 1840 campus plan, turning the external focus of campus away from State Street Row and inward towards the Diag and the academic core of the university (Mayer, 64).

The General Library featured a rounded reading at the north end of the building, while the southern and rectangular end housed the stacks. Another notable feature of the library was the presence of two towers, one which housed a set of bells donated by E.C. Hegeler, J.J. Hagerman, and Andrew Dickson White (Mayer, 65). By the early part of the twentieth century, the library had outgrown its home and was demolished in 1918 to make way for the new General Library, which was built on the same spot. The new General Library, later renamed the Harlan Hatcher Library, opened in 1920 and to this day the library continues to sit at the academic heart of campus.

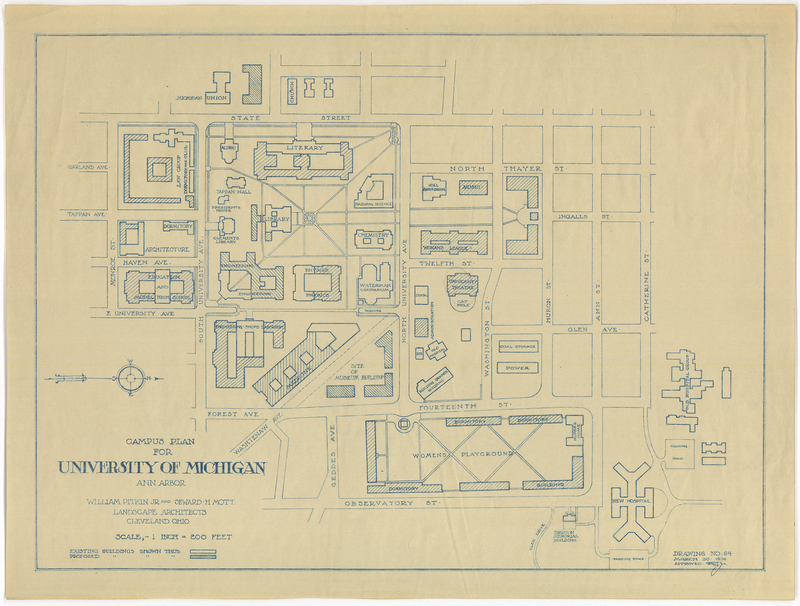

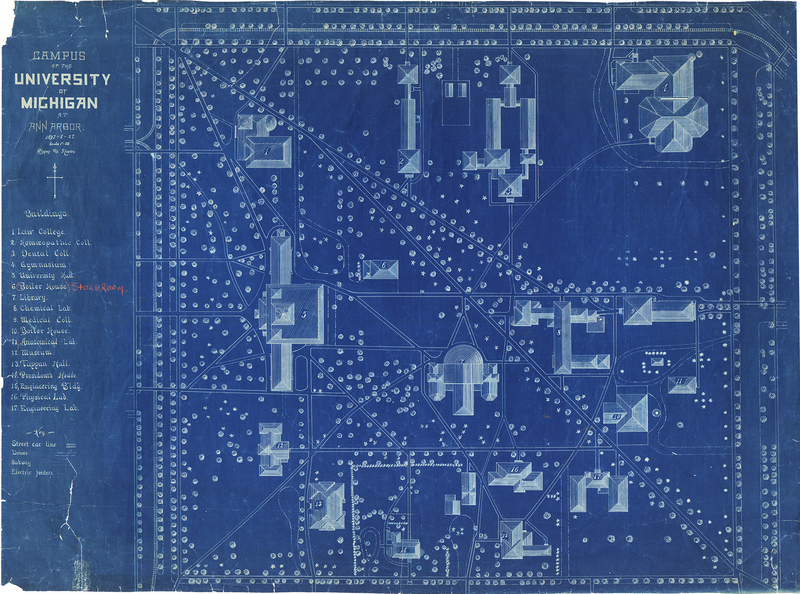

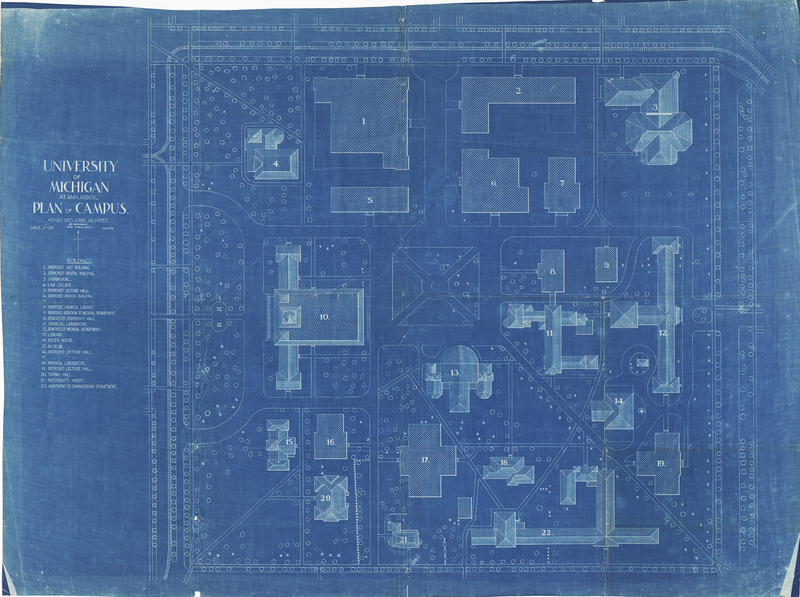

Cobb Plan (1898)

Henry Ives Cobb was first approached in 1895 about designing a new art building for the University of Michigan. However, after examining the layout of the existing campus Cobb determined that it would be impossible to design such a building without first knowing where the new building would be built. Additionally, Cobb felt that in order to determine the site of the building, he would need to take into consideration the entire campus (Mayer, p. 68). So a plan of the existing campus, seen below, was drawn up and sent to Cobb. He drew two different designs for the new art building, and the drawings were used to raise funds for the art building. In the process, though, Cobb was authorized by the regents to create a new proposal for the organization of campus (Mayer, p. 69).

When Cobb delivered his master plan to the regents, there were three distinct deviations from previous ones, including the most recent from 1840. Cobb’s plan was the first to deal with the entire 40 acres as a whole, rather than dividing it into zones, which had been done in the past. Secondly, Cobb introduced the idea of a central open square whose main access was via North University Avenue, much like Ingalls Mall today. Additionally, Cobb wanted all the buildings surrounding the central open space to have a second inward-facing orientation as well (Mayer, 70). Sadly, Cobb’s spaces were not well defined and the Diag became de-emphasized. His idea for a northern entrance to the Diag did eventually allow for the expansion and inclusion of Ingalls Mall as part of Central Campus.

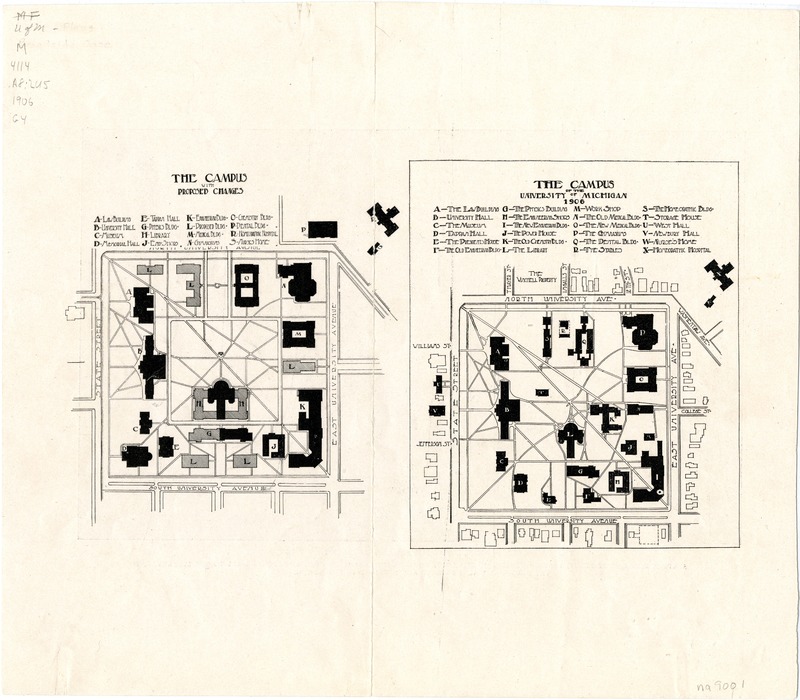

Lorch Plan (1907) and the Diag

As the university continued to grow beyond State Street Row, without any set plan or real organization, the regents created the Committee on Location of Buildings in 1907. The new committee was to accommodate the siting of the new Alumni Memorial Hall and other buildings. The committee was composed of regents, faculty, and architects. Emil Lorch, though an architecture professor at the time, was not selected to be part of the committee, but instead served as secretary (Mayer, p. 80).

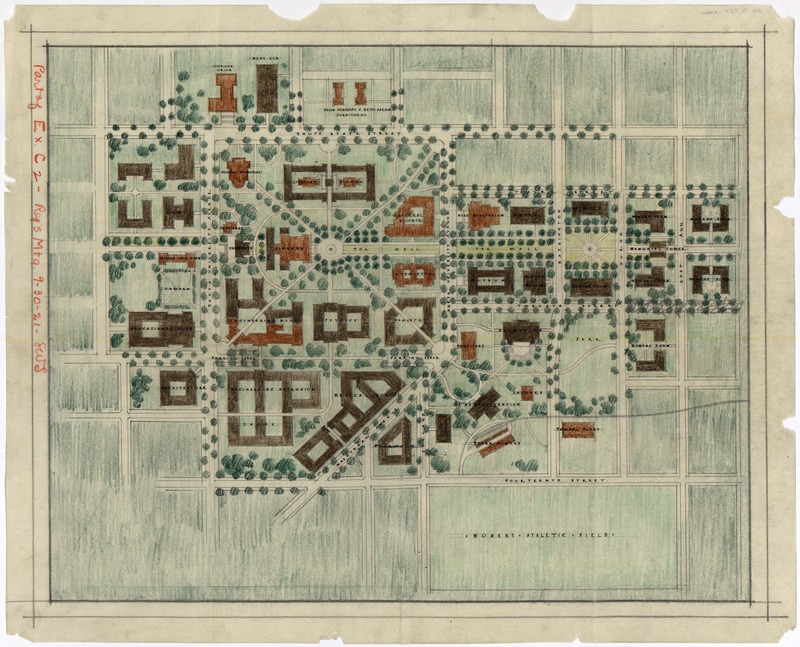

In 1907, before the committee met, Lorch drew up a plan for campus and presented it to the group, but the plan was never submitted to the regents and therefore was never formally adopted. While his proposal was never official used, it did strongly influenced subsequent plans, including the siting and design of several buildings, such as the West Engineering and Kraus buildings. Additionally, concepts defined by Lorch are evident in every campus plan prepared since, including the creation of a new mall, which became Ingalls Mall (Mayer, 80-82).

Emil Lorch drew these artistic renderings of campus in 1906. Lorch’s proposal had three distinguishing features. After Cobb’s de-emphasis of the Diag, Lorch highlighted the historical and functional importance of the Diag and suggested lining it with trees to further strengthen its permanence. He, also, advocated a central mall on the same axis as the library, even extending it over North University and placing the proposed Hill Auditorium at the northern terminus of this mall. The third element of Lorch’s plan was the creation of a central shady square at the heart of the campus (Mayer, p. 82).

One of the downsides of Lorch’s plan was that it only dealt with the 40 acres and did not adequately address the areas outside the original campus. Additionally, other members of the committee objected to Lorch’s placement of Hill Auditorium and it was due to the conflict that Lorch’s plan was not submitted to the regents until the fall of 1911 (Mayer, p. 82).

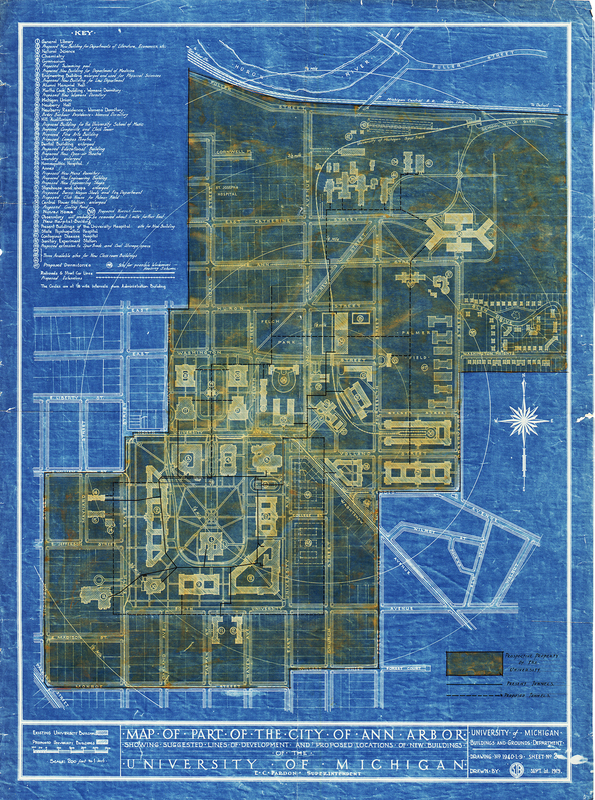

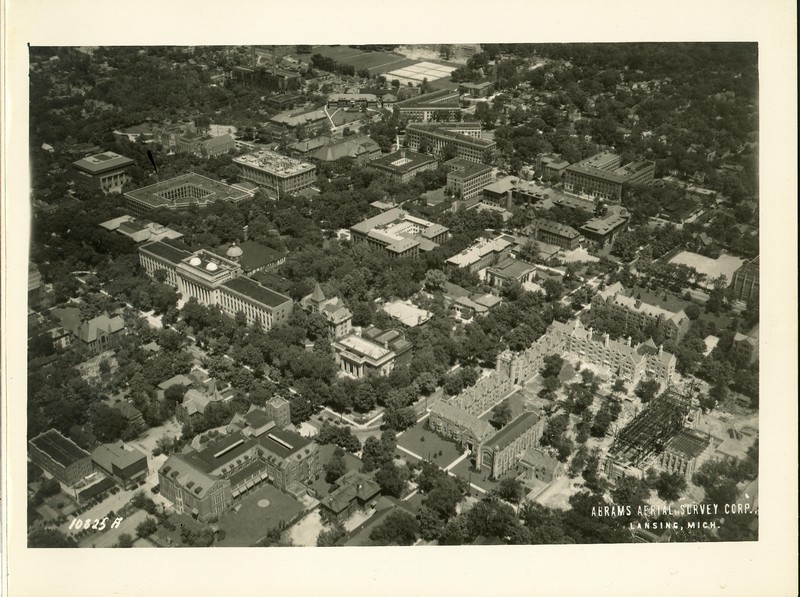

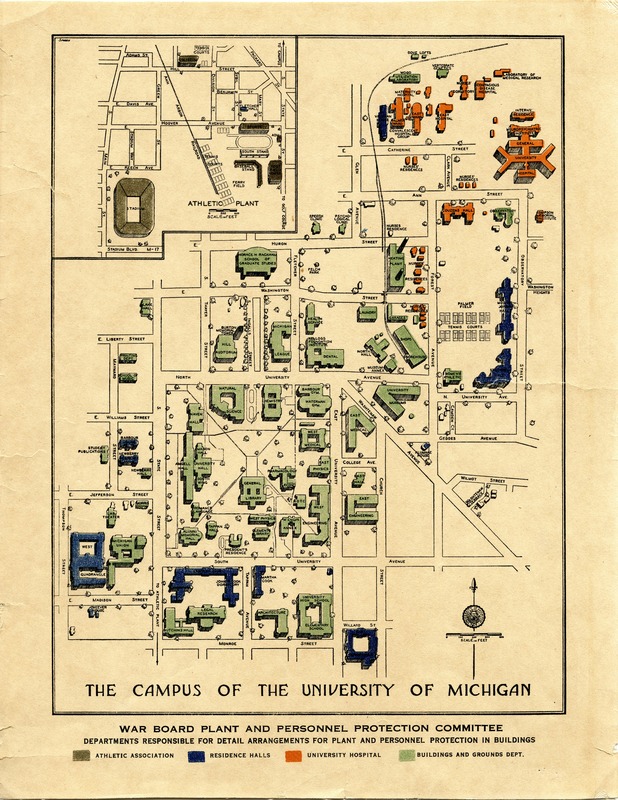

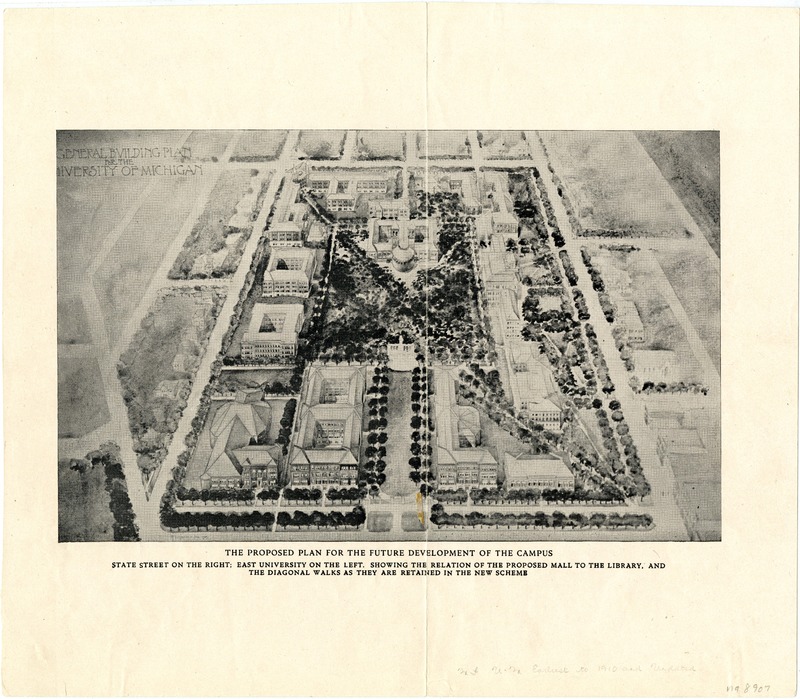

The Burton Plan (1921) and Expansion in the 1920s

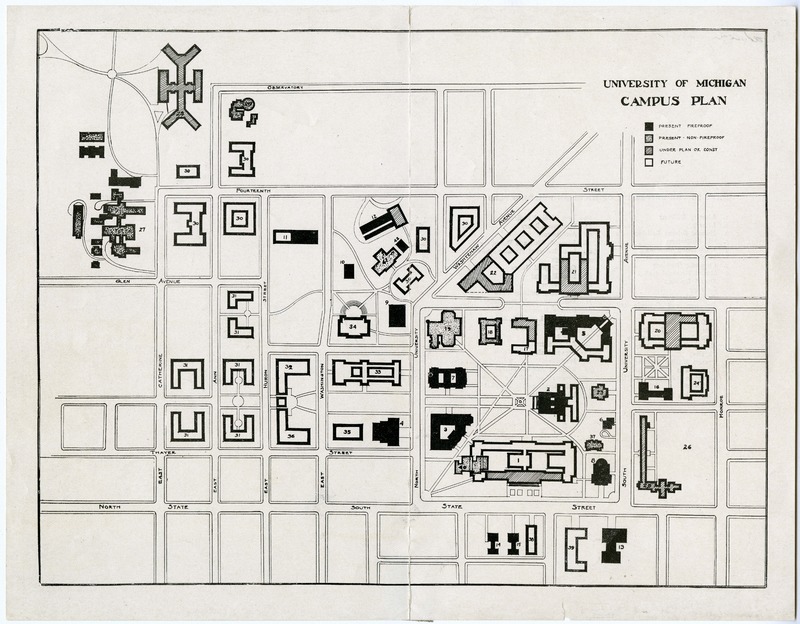

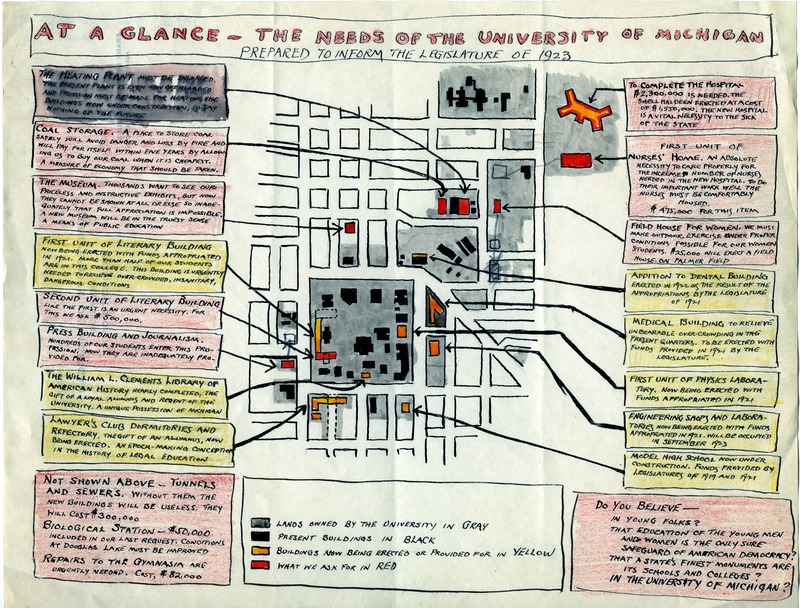

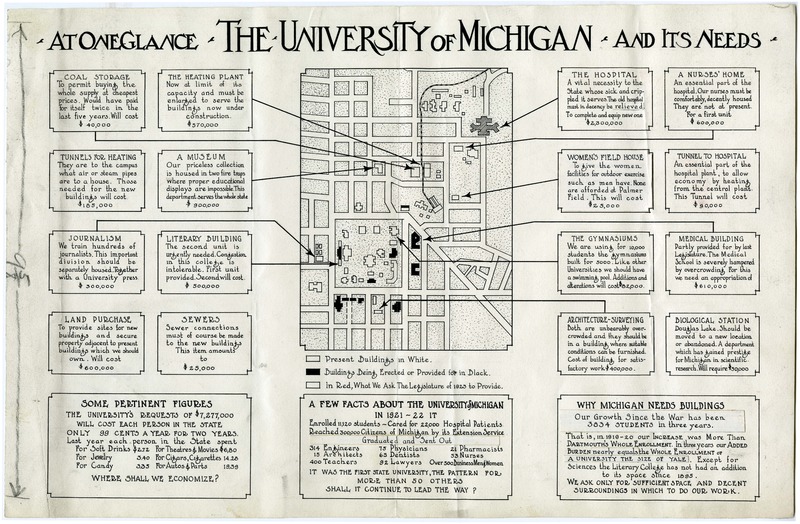

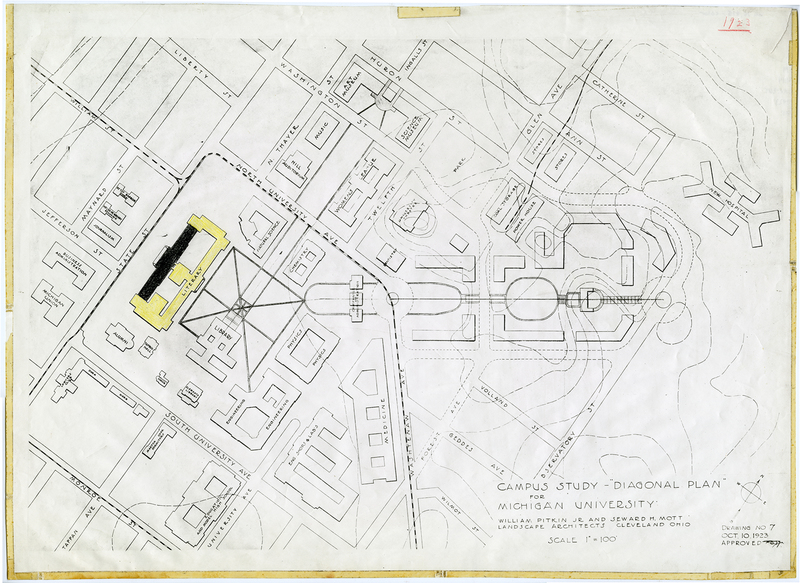

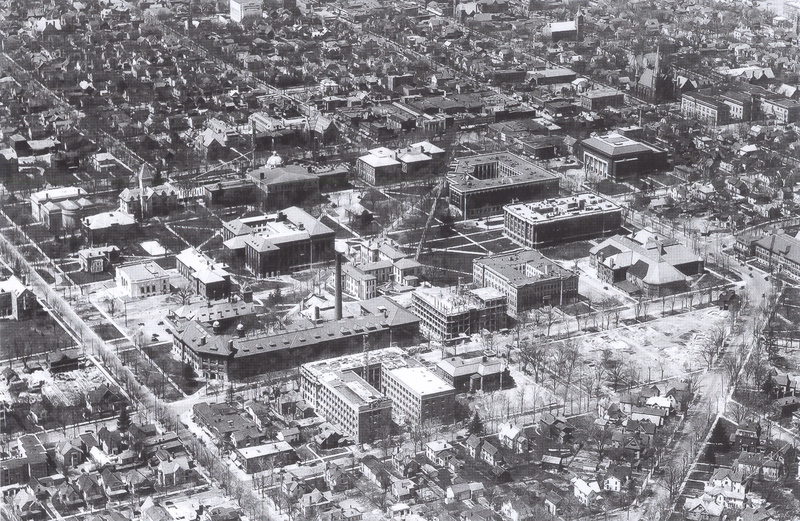

During the early decades of the twentieth century campus continued to grow, first under President Harry Burns Hutchins (1909-1920) and later President Marion Leroy Burton (1920- 1925). None of the previous plans could have anticipated the building boom that took place in the 1920’s under President Marion Leroy Burton and it became increasingly more apparent that a new plan was needed to codify the expansion.

Burton accomplished much during his very brief tenure at the university, including reinstating a visual order to campus and integrating the new official master planning function into the administrative structure. With the creation of the Comprehensive Building Program, all plans now had to receive approval from the regents, so Burton’s in 1921 was the first to be formally adopted and implemented since the 1840 plan (Mayer, 101-102).

The Burton plan dramatically expanded campus beyond the original 40 acres given by the Ann Arbor Land Company. It defined the mall concept for the northern expansion, proposed a strongly defined central open space and the use of walking paths to link various parts of campus. It also saw the Beaux Art style spread widely across the campus (p. 102). Unfortunately, President Burton died unexpectedly in 1925, but his plan effectively continued to guide development until the 1950s.

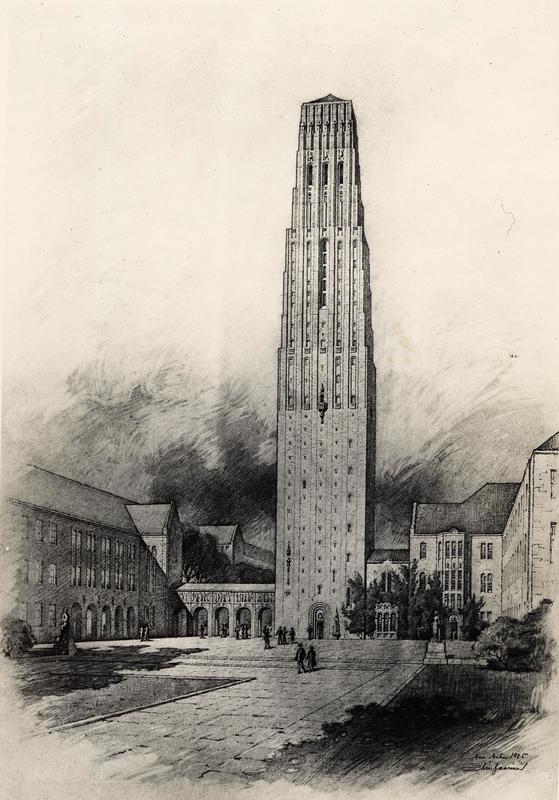

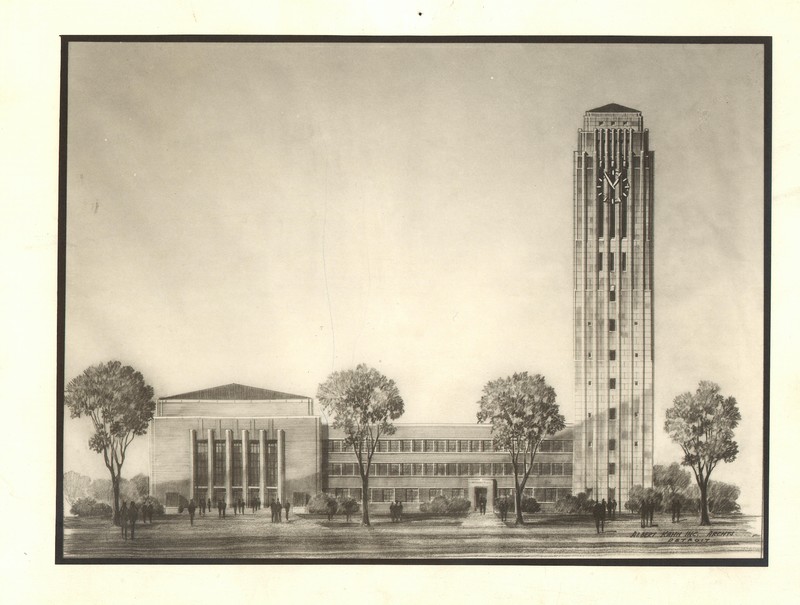

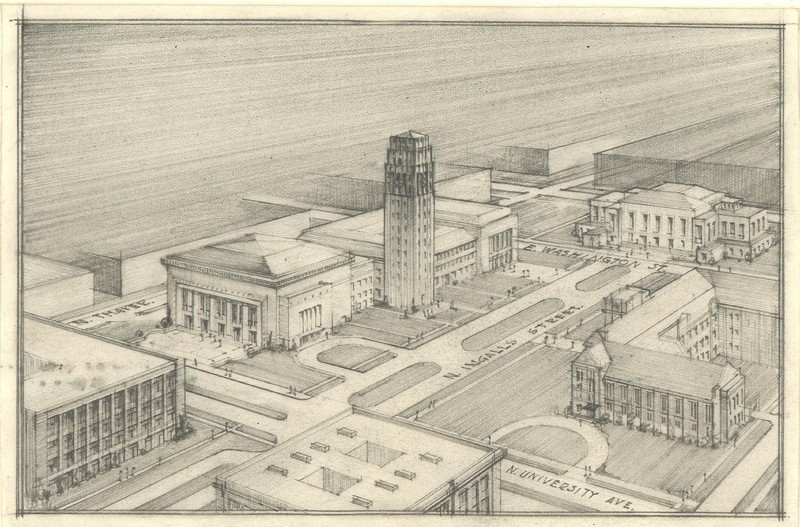

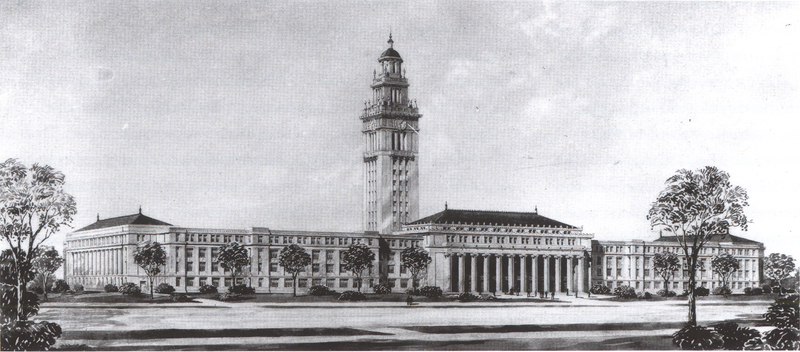

The Proposed Music School

One of the projects that President Burton championed during his tenure was the raising of funds for a bell tower. Unfortunately, he died before the tower was constructed and it was decided that the tower would be built as a memorial to him. Working with Albert Kahn’s firm, it was Eliel Saarinen who first proposed placing the tower at the terminus of the mall and between the League and a proposed music school, to be built behind Hill Auditorium. When it came time for the final design, Saarinen was unavailable, due to other obligations, and Albert Kahn and Associates drew up the final plan (Mayer, 114).

Kahn proposed a complex attached to Hill Auditorium, including the bell tower, and a music building. However, the university could adopt only parts of the plan. As the university did not own the proposed land, it had to be re-sited to just northeast of Hill Auditorium. Additionally, the proposed music school was eliminated as the funding went instead to the construction of the memorial tower with the promise of including music classrooms. Due to limited funding the height of the tower was reduced as well.

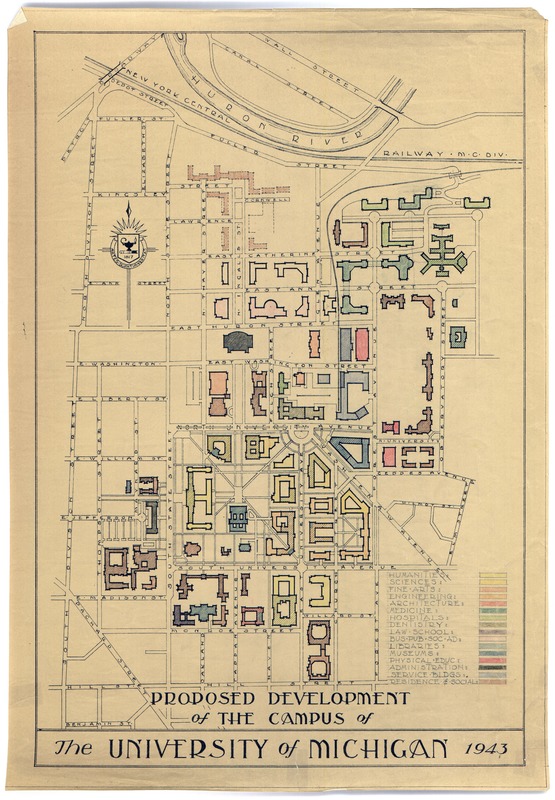

1943 Plan

The rapid and unguided expansion of the 1920s demonstrated the growing need for a new plan to oversee the development of campus. With the outbreak of the Second World War construction efforts ceased, giving the university the opportunity to re-examine its changing needs and devise a plan for the postwar era. Two plans were created during the span of the war, one in 1941 and the other in 1943. Both were updates to Burton’s plan and those of Pitkin and Mott, and reflected the changing priorities and conditions of the University, including the increase in the student population between 1910-1920. The 1943 plan sited many of the projects in the postwar era and continued to guide planning throughout the 1950s (Mayer, 1118-120).

1963 Plan

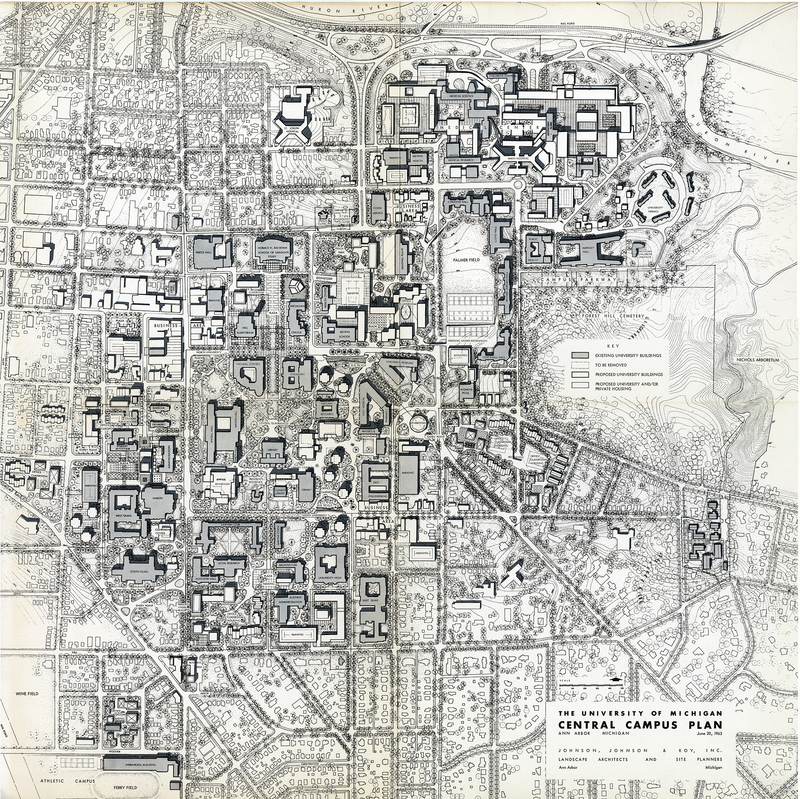

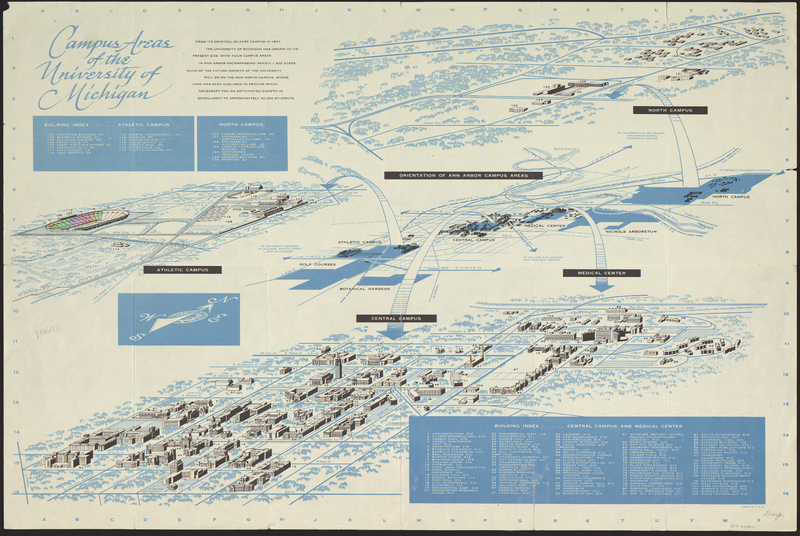

In the 1960s the University anticipated the student body growing to around 40,000 students. With this in mind, the university understood that a new plan that looked to the future would be necessary. Johnson, Johnson, and Roy were hired as consultants and in turn were given a list of requirements for the new plan. It made the campus beautiful and orderly while maintaining easy circulation of pedestrians and vehicles. Most importantly the new plan had to be flexible enough to meet the future needs of the growing university (Mayer, 132). The plan, developed in consultation with Johnson, Johnson, and Roy, introduced the concept of "framework planning." There was less emphasis on architectural styles and more on community interface, walkways, open space, road systems, parking systems, etc. This new style of framework planning became a pioneering effort for campus planning across the country (Mayer, 133).

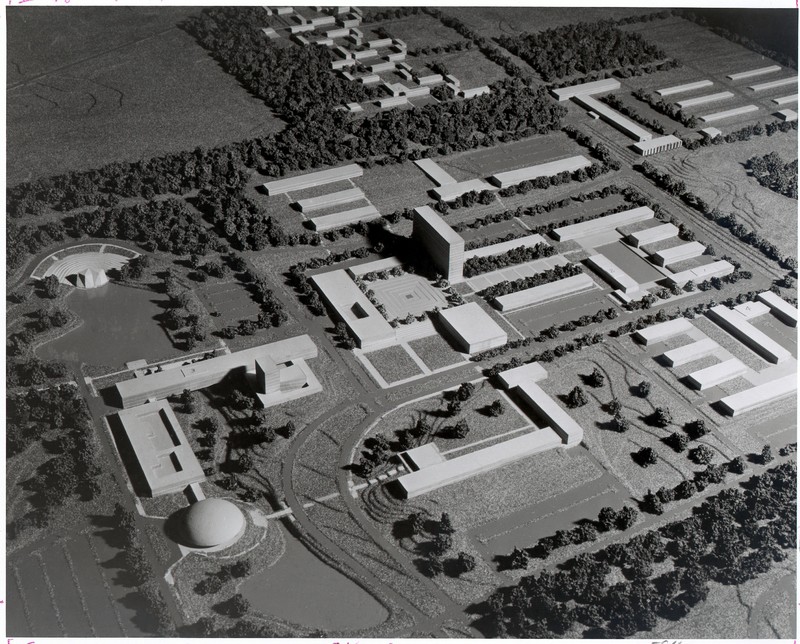

The new plan also looked beyond the original forty-acres and included the development of North Campus. Eero Saarinen, son of Eliel Saarinen, developed a master plan for North Campus, but only the design for the Earl V. Moore School of Music was used (Duderstadt, p. 275). The principles set forth by the 1963 plan and the ideas behind it are still influential, making the campus of today.

Creating a Campus

Wall Maps

![hs16929[1]_Proposed Campus Plan for University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.jpg hs16929[1]_Proposed Campus Plan for University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.jpg](https://apps.lib.umich.edu/online-exhibits/files/fullsize/220d76d2de89d6e09711e3ae03fd8f26.jpg)