Anna Caulfield McKnight

Anna Caulfield McKnight accomplished a great deal in her lifetime. She was highly educated and travelled broadly as an independent woman in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She built her reputation as a respected intellectual in the art field well before she married her husband at the age of thirty four. McKnight was likewise involved in politics and business to a remarkable extent. Today, her life can be examined through several points of interest, from its impact on arts education, history, and women's history to the technological significance of her slide collection.

Family Connections

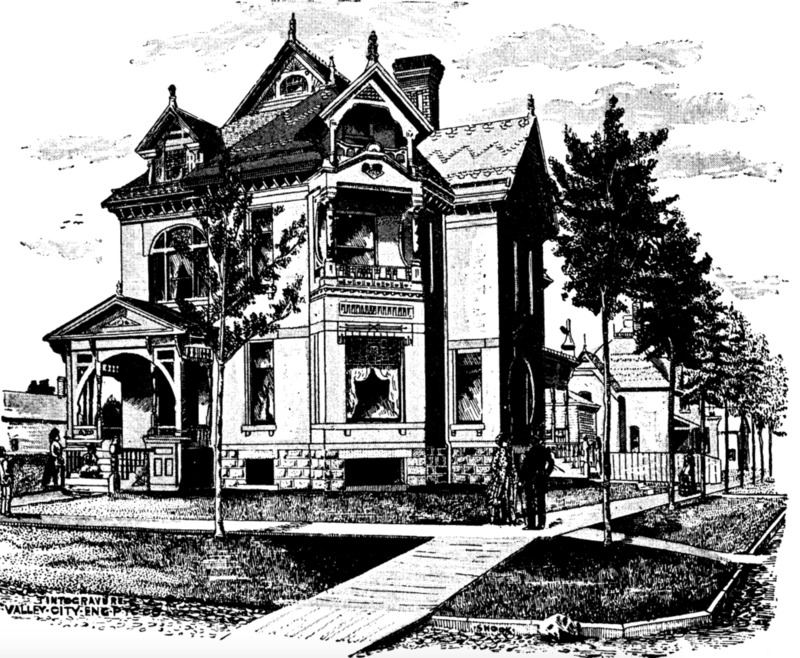

The Caulfield family first made a name for itself in the United States with the arrival of John Caulfield, Anna's father. In 1857, at the age of nineteen he sailed from Ireland, and, after arriving in New York, made his way to Grand Rapids. There, the young Caulfield began his career as a grocery clerk for a major merchant, George W. Waterman. Caulfield would go on to run his own business, and in his retirement become a prominent real estate broker. He married Esther Egan in 1864 and they had seven children, making Anna one of five daughters and two sons. The Caulfields were also active in the Democratic party and devout members of the Catholic Church.

Anna was born in 1873. Her family's reputation and upper-class standing afforded her the opportunities that led to her productive life as a lecturer, philanthropist, and world traveller. She was educated first at Sacred Heart Academy in Detroit and went on to pursue secondary education at the Harvard Annex (Radcliffe College) before taking off to study and travel throughout Europe in the early 1890s.

Remarkably for a woman of her time, Anna pursued the majority of her career and established her professional reputation independently. She travelled mostly by herself across Europe and the East to build her lantern slide collection. During this time, Anna fostered political connections in several countries. She met with the Pope in Rome, the French government named her a member of the Fine Arts Department for the 1900 Paris Exposition, and she was honored by several presidents. In 1897, President McKinley was so impressed by one of her early lectures that he personally invited her and her mother to spend an evening at his summer home in Lake Champlain.

While Anna's husband, William F. McKnight, was a successful lawyer with numerous political connections himself, none of this contributed to Anna's early career, as they were not married until 1907. Her charm and determination of character seem to have been the key to her early success. Her lectures were highly praised from the beginning. A reporter for The Catholic Sunday Union covered the lecture in front of President McKinley and wrote, "The lecture was indeed of itself, a matchless piece of oratorical elocutionary and educational work. This young girl is gifted with a voice of metallic clearness and of silvery sweetness, the voix d'or." Clearly, Anna had a propensity for public speaking. This, in combination with the fairly new practice of lectures illustrated by colored slides, must have impressed her audiences and gained her the respect she needed to be able to travel and have access to so many of the world's cultural treasures.

A Prolific Career

Anna's illustrious career began with her strong education. After returning from Sacred Heart Academy, she gave some of her first art talks when she joined the Ladies' Literary Club. Anna was secretary of the club, but the success of her talks resulted in her friends encouraging her to "enter the lecture field." Heeding their advice, Anna pursued her secondary education. At the Harvard Annex (which became Radcliffe College in 1894, just after Anna left), she studied with Charles Eliot Norton, an esteemed professor offering the only course in art history at the time. With his encouragement and her parents' support, Anna left in 1892 for four years of study in Europe. In Rome she studied with the prominent archeologist, Commendatore da Rossi. She also travelled to Paris to continue her education and lectures. Anna returned home after four years and her success quickly spread in the United States.

Over the course of her life, Anna continued to travel around the globe and give lectures. She spoke for many prominent institutions, including the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the National Arts Club in New York, the Boston Art Club, the Hartford Art Society, the Art Institute of Chicago, Vassar College, and the Congressional Club in Washington D.C.

In 1907 Anna became Mrs. McKnight after marrying Grand Rapids lawyer and businessman, William F. McKnight. She was thirty four years old, and during this period in her life, she turned her attention to work beyond the fine arts. Anna McKnight began serving in a variety of civic roles. She was appointed to several congressional committees such as the National Civic Federation, the National Conservation Congress, and the second Pan-American Scientific Congress. Upon her husband's early death in 1918, McKnight succeeded him as the president of his enterprises, the White River Timber Company and the Miami Lumber Company, and as secretary-treasurer of the Dickie Mining Company. With these engagements, McKnight began to incorporate political and entrepreneurial interests into her career as a public figure.

After her husband's death, McKnight began travelling again. She lectured abroad in London and at the Louvre in the 1930s. The French government appointed her Officier de l'Instruction Publique. In the post-war years, McKnight also went to India and Russia, developing further lectures on these cultures.

McKnight continued her philanthropic work at home and abroad. She was the vice president of the American Artists Professional League of Paris in 1938-40. She likewise organized and oversaw the Alliance Francaise and the Drama League of Grand Rapids. McKnight served on many women's clubs and leagues, both at the state and national level. Her service of the International Council of Women in Paris was just one example of civic connections she maintained between the United States and France throughout her life.

Anna Caulfield McKnight passed away in 1947. While little work exists on the significance and impact of her life, her slides provide an insightful view into the world of the early 20th century, as witnessed by a remarkable, independant woman. Many of the views she documented no longer exist or have been altered with the passing of history. McKnight's collection stands out as one of the finest early aids to a now essential part of artistic education - the illustrated lecture. Not only important documents of history, these lantern slides can also be appreciated as artworks in and of themselves.

Lantern Slides: An Historical Technique