Fans & Readers

The cult of Jane Austen truly got underway roughly fifty years after her death in 1817, as posthumous fragments of writing, unpublished fictions, letters, and first-hand recollections by her surviving relatives began to pour forth from the press; the beginnings of critical and scholarly writings about her followed shortly thereafter. A second great wave of Austen-related publishing took place in the 1920’s, largely due to the work of the Oxford published and editor R.W. Chapman, who defined the canon of Austen’s texts for the twentieth century. While Austen’s reputation has gone through many transformations since her death, our current impressions of her work grow richer as we consider her earlier fans.

Memoirs, Letters, and Posthumous Publications

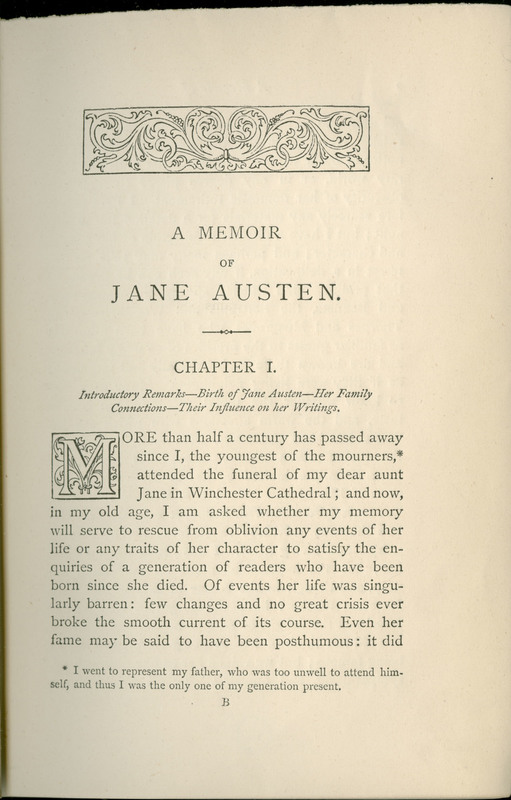

A memoir of Jane Austen was written by Austen’s beloved nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh. The first edition of the memoir was published in 1870, fifty-three years after Jane Austen’s death. This is a sixth edition published in 1886 with the original preface from 1870.

The second and subsequent editions of the memoir prominently debuted Lady Susan. After Jane’s death, the owner of the manuscript, Lady Knatchbull, allowed its publication against James’s wishes. Lady Susan is Jane’s only mature fiction written in the epistolary style. Like Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, both initially written in the epistolary style, this version of Lady Susan could possibly be a preliminary draft of a novel which would have later employed a direct narrative style.

This memoir is also noteworthy for its inclusion of The Watsons. An unfinished novel, The Watsons was written between 1803 and 1805 after Austen revised Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. It was written in Bath after her father’s death. James speculated that Jane did not complete The Watsons because she was struggling with the characters, but other theories claim she was too depressed to complete the novel. Caroline, James’s sister and the owner of the manuscript, gave permission for its publication against her sister Anna’s wishes. The Watsons is the only work Austen wrote between the first drafts of Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, and Northanger Abbey.

(Ha Eun Lee, Brooke White)

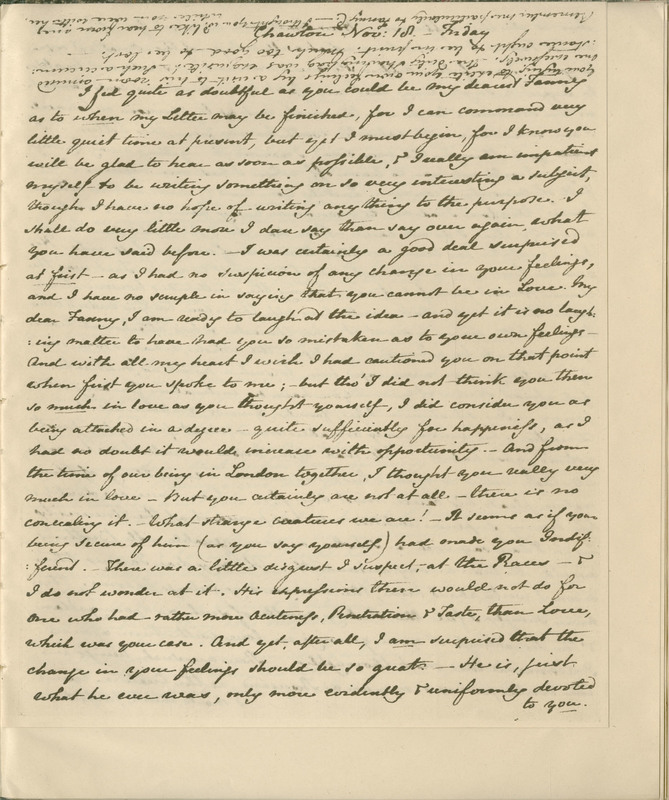

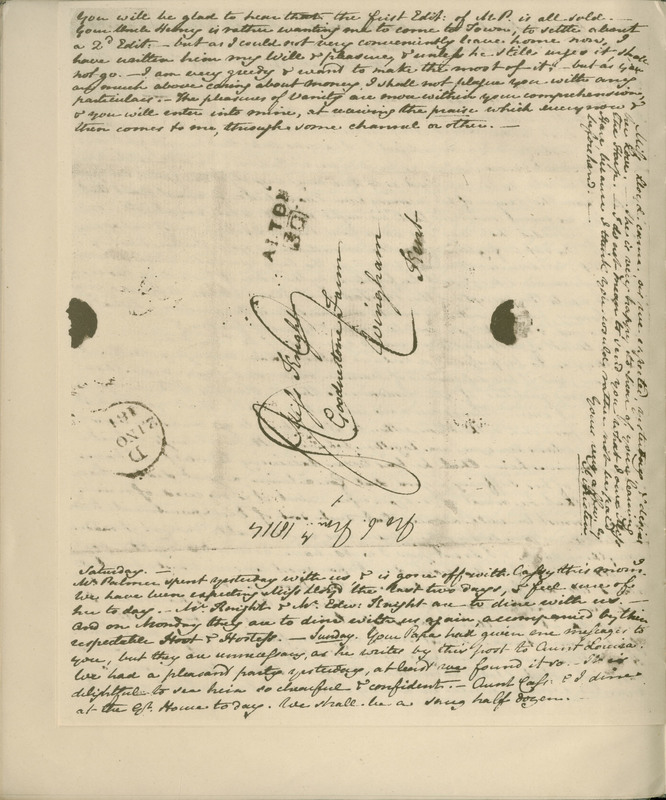

Jane Austen is estimated to have written 3,000 letters during her lifetime. These letters to her niece Fanny Knight are a good example of the conventions of letter writing in the Regency period. The paper the letter was written on was folded and then sealed. Envelopes were not used due to the extra expense. To cut down on expenses, writers would use as few pieces of paper as possible. Whoever received the letter would have to pay for it, and the thinner the letter, the cheaper it would be. Jane Austen would have written these letters with a quill pen, made from a goose or crow feather. Metal pen nibs had been invented, but the price again impacted the conventions of letter writing.

These five letters offer a rare glimpse into Jane Austen’s inner life through the candid and informal writing style she used in her correspondences with loved ones. Originally published in 1884, the Lord Brabourne edition of the letters omitted certain “family details” which were left untouched in later publications. While she writes to Fanny about many events in her daily life, including the impending publication of her novel Mansfield Park, the majority of the letters are devoted to offering her niece some much-needed love advice. Fanny’s predicament—whether or not she should consent to marry a man of high standing who she does not love – echoes the internal conflicts faced by many of Austen’s heroines, and the author seems unsure herself what her niece should do.

(Ryan Lakin, Alexandra Wisbiski)

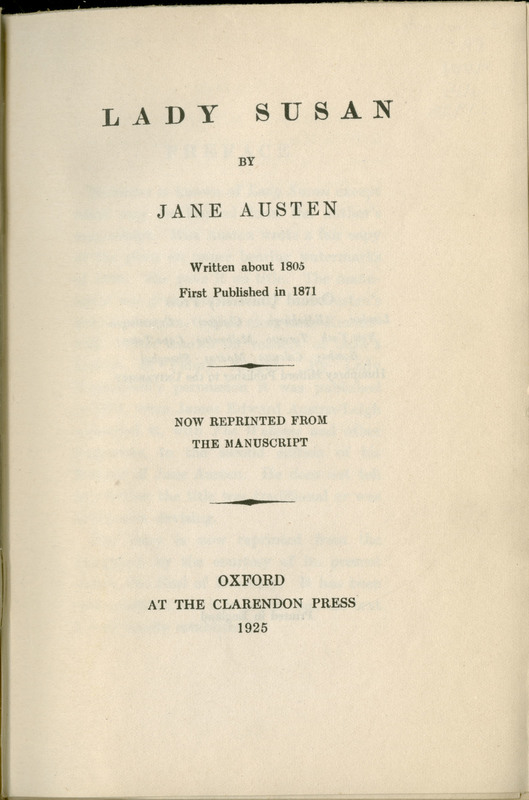

Lady Susan is a novel in epistolary style written by Jane Austen around the year 1805. This edition of the novel was published in 1925 and contains an index of all the changes from the original manuscript to the current copy. This version itself is quite plain, containing no cover art or any illustrations. The novel was originally completed but not published during Austen’s lifetime. It first appeared in print in 1871 in the 2nd edition of James Edward Austen-Leigh’s A Memoir of Jane Austen along with two unfinished works by Jane Austen. The untitled novel was originally gifted to Austen’s niece, Lady Knatchbull, who then gave permission to Austen-Leigh for publication. It was titled Lady Susan. The memoir was commissioned by the Austen family after the deaths of Austen and her brother.

Lady Susan is a humorous story that follows the escapades of the beautiful widow and accomplished flirt, Lady Susan Vernon, who gets mixed up with multiple lovers while also trying to marry off her daughter, Frederica, who is opposed to the idea. Lady Susan was never a well known novel of Jane Austen’s, but was recently adapted to the big screen under the title Love and Friendship.

(Heather Barnell, Megan McKenzie)

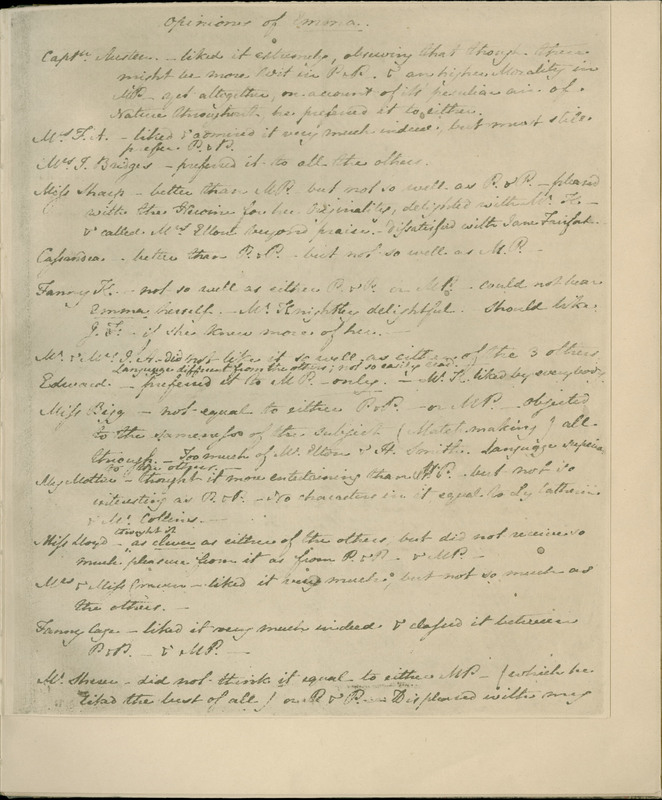

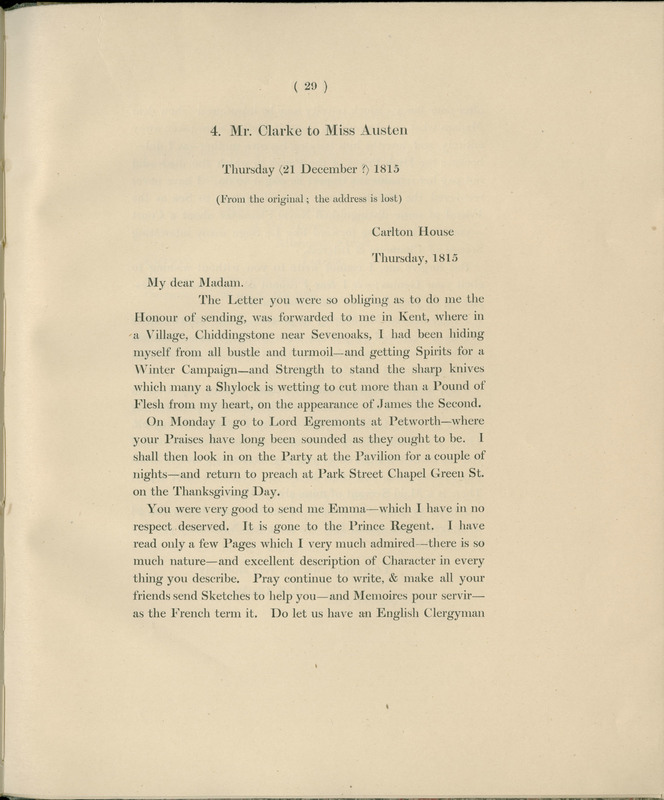

With only 350 copies printed, this book provides rare insights into the construction of Austen’s early novels. Plan of a Novel depicts opinions and suggestions from Jane Austen’s trusted family, friends, and acquaintances regarding her early works such as Mansfield Park and Emma. These give an interesting insight into Austen’s writing and editing process as well as personal insight into who Austen’s friends and family were. Some notable contributions included the opinions of Mr. Sherer, a reverend who was at odds with Austen’s description of clergymen, and Fanny Knight, Austen’s favorite niece, who provided detailed feedback. It’s interesting to note the sheer number of opinions Austen took into account for her novels. For Mansfield Park Austen asked fourty-one different opinions, including some families, and for Emma there are fourty-four different opinions. Another intriguing aspect of the book is that people were very honest in their feedback, such as that of Mrs. Digweed’s opinion of Emma, “did not like it so well as the others, in fact if she had not known the Author, could hardly have got through it." Mr. Cockerell, another acquaintance, liked it “so little, that Fanny would not send me his opinion.” Plan of a Novel also includes some of Austen’s letters to Mr. Clarke, a librarian and admirer of Austen’s work. These letters further highlight what Austen might have taken into consideration in her editing process. The book also includes Austen’s notes on her novels’ profits and dates of exposition.

(Chloe Chung, Brittany LeGwen)

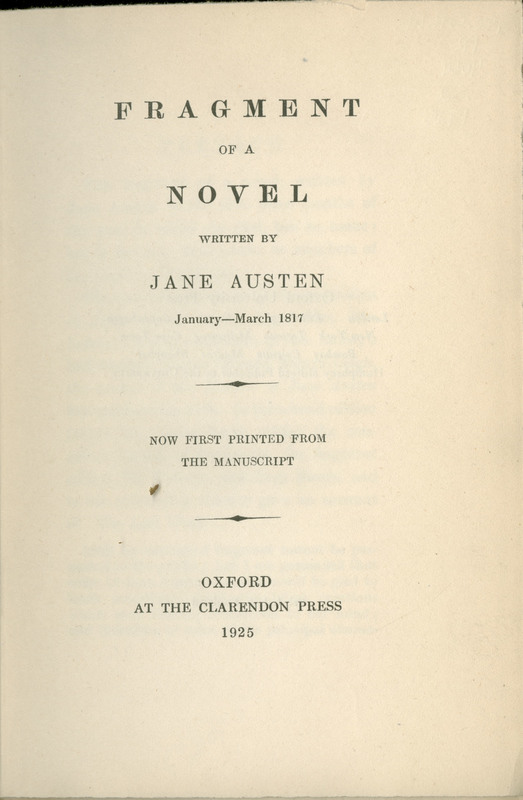

Fragment of a Novel was the last work written by Jane Austen before her death in 1817. The work was unfinished and untitled, but it was referred to by Austen’s family as Sanditon, which now remains the work’s title. Austen’s niece Anna was the first inheritor of the manuscript and it was later passed onto her great-great grandniece who decided to publish it in 1925. It was her belief that since many lines of the work had previously been published in the second edition of Memoir of Jane Austen by Jane’s nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh, the entire novel should not be withheld from the public.

Following its publication in 1925, book reviews and newspapers rejoiced at the release of Austen’s final work. Controversy still surrounds the moral implications of publishing Austen’s work posthumously however, as it is unknown if Austen would have wanted it to be published as it was. Even so, many scholars and fans are grateful for its publication. Fans continue to enjoy the work as it is republished and as many contemporary writers strive to complete the unfinished work. Notably, one of the first attempts, Sanditon by Jane Austen and “Another Lady” was a best-seller in England throughout 1975.

This first edition of Sanditon remains verbatim to and unedited from Austen’s original manuscript. It remains in its long-paragraph form, and the editor, Robert William Chapman, includes notes on Austen’s crossed-out passagesfrom the manuscript in the back of the work, allowing scholars and fans to follow Austen’s writing process and genius.

(Jennifer Emery, Kayla Kaszyca, Lauren Zavicar)

Reading and Responding to Austen

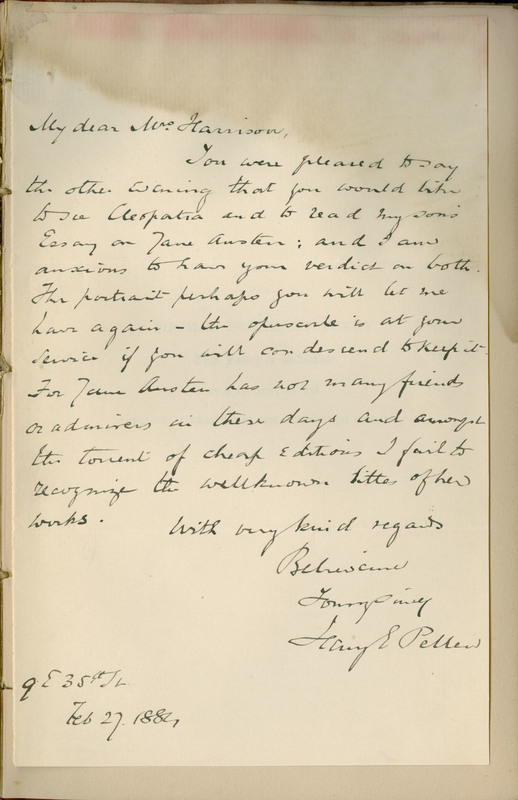

Published 80 years after Jane Austen’s major works, this critical study of Jane Austen focuses on her mastery of the mundane, and her clever and witty writing. This copy of the dissertation features a handwritten letter by the author’s father, Henry Pellew. This critical study, as well as the senior Mr. Pellew’s letter, exhibit the low readership and popularity of Jane Austen at the time. Although now Jane Austen is a highly respected English novelist, she started out with a relatively modest fame. When she first published her novels anonymously, they were well received but not widely discussed in academic spheres. It was not until later in the nineteenth century that her novels began to be approached from a more scholarly literary standpoint. Austen’s increased readership and respectability coincided with the publication of her biography, A Memoir of Jane Austen, written by her nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh. This increase in popularity caused a reissuing of her works in cheaper editions.

George’s dissertation displays the emerging respect and critique for Austen’s work. His father’s letter reinforces this shift: “For Jane Austen has not many friends or admirers in these days and [among] the torrent of cheap editions I fail to recognize the well known titles of her works.” Pellew’s work on Jane Austen was the beginning of a now massive body of scholarly work analyzing Austen’s writings.

(Ariana Hunter, Sophia Lusk)

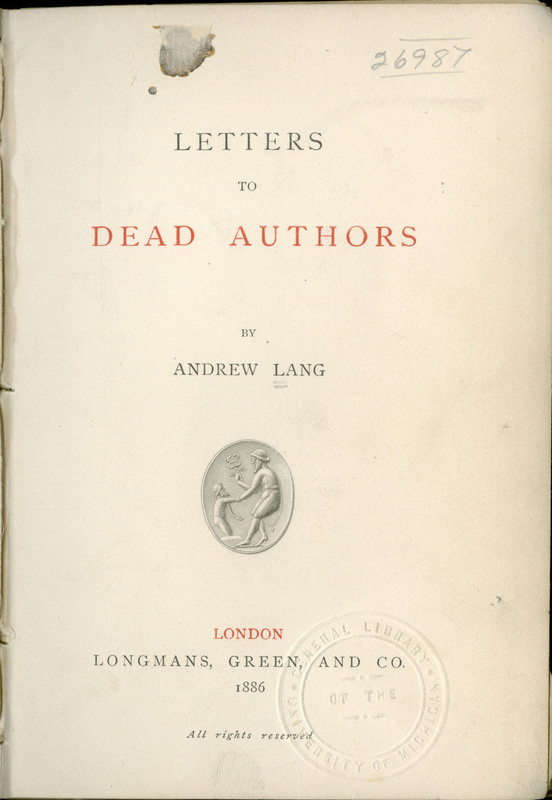

During the Victorian era, literary criticism served as a medium through which wide audiences could gain deeper insight on a broad spectrum of novels and authors from multiple disciplines. Literary criticism also provided commentary on social and cultural trends and production, which authors either reflected, criticized, or transformed. In this time period, Andrew Lang came to prominence as an author of fairy tales, a translator of ancient poetry, and a historian. During the 1880s, he was asked by the editor of the St. James Gazette, a conservative political newspaper, to write a column addressing letters to dead authors. Due to Lang’s expansive literary knowledge and skill, he was well-suited for this task, and cleverly penned each letter in the style of the author to which they are written.

Letters To Dead Authors encompasses sixteen of Lang’s letters to renowned authors, from English masters such as Alexander Pope and Charles Dickens to ancient, worldly writers such as Omar Khayyam and Herodotus. It is unsurprising, therefore, that Jane Austen is included amongst their ranks. However, she stands alone as the sole female author and influencer in the collection. Whilst Lang celebrates the likes of Edgar Allan Poe, his address to Austen is relatively sharp. He revives Austen’s work almost half a century after their publication, where he finds her stories are ill-placed amongst more “complex” literary novelists of his time period. While he expresses respect for Austen, his criticism offers a unique perspective differing from the reverence often ascribed to her.

(Janelle Jajou, Miranda St. Amour)

The Wit and Wisdom of Jane Austen is a collection of Jane Austen’s quotations and comments that have entertained readers for two centuries. Discussing topics from the specificity of a lady’s accomplishments to broad ideas on human nature, these excerpts from Austen’s writings provide the reader with a sampling of the main themes of Austen’s novels, and an opportunity to enjoy the “wit and wisdom” that has caused Austen to be so enduringly popular.

Austen only reached modest levels of fame in her time and published anonymously. While she did receive a few positive reviews, her novels were mostly read by men and women in high society. She became more popular after her nephew’s publication of Memoir of Jane Austen which portrayed her as “dear, quiet Aunt Jane”, a personality that was far more palatable for the general public. Her popularity soared and competing groups of “Janeites” began to appear at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Starting around the late 1980’s, the Jane Austen culture shifted into an industry of empowering, entertaining and speaking to women. By 1995, a flood of Austen adaptations began to be produced. From that time onwards, hundreds of books and scripts have modernized Austen’s general storylines but continue to draw ideas and inspirations from her works dating back to the 1800’s. This book is an example of the continued hunger of the reading public for more, new ways of consuming Jane Austen.

(Catherine Budd, Mackinzie Cole, Emma Kirst)

Austen’s formative years as an artist correlated perfectly with the growth of the literate population. There was a steep rise in the volume of publications, especially novels. This helped with her popularity at the time her books were published. For example, Sense and Sensibility (published in 1811) made back its printing costs quickly and went for a second edition in 1813. The book was translated into French and Danish in the nineteenth century. Her books were not necessarily best sellers at their time, but nowadays, Austen’s work permeates popular culture in a multitude of ways. Both her novels and Jane Austen herself have achieved a “cult status.”

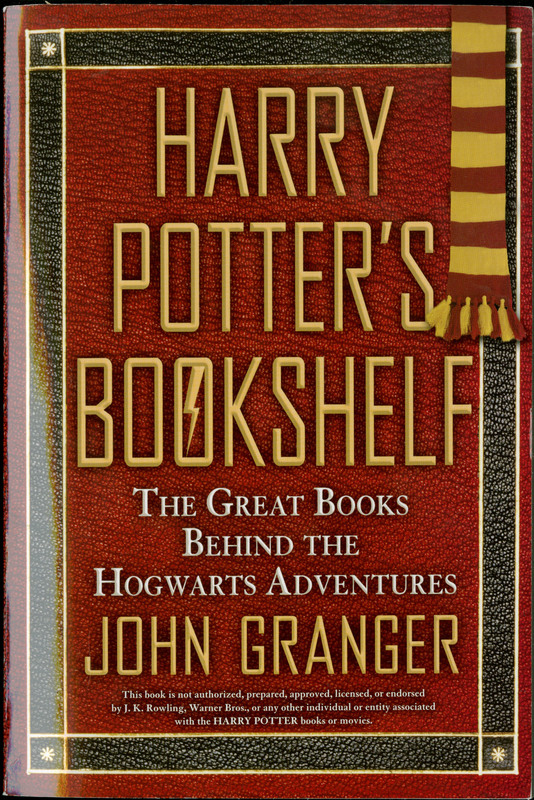

When we think of books that have a wide-reaching, widely-translated impact on pop culture, the Harry Potter series comes to mind. Like Austen’s works in their day, Harry Potter has been translated into many languages and reprinted many times. John Granger’s Harry Potter’s Bookshelf: The Great Books Behind the Hogwarts Adventures is an analysis of the influence of famous works and authors on JK Rowling, including Shakespeare, Dickens, the Brontë sisters, and, of course, Jane Austen. According to the chapter “Pride and Prejudice With Wands,” JK Rowling has named Austen as the “author she admires most,” and says she has read Emma “at least twenty times,” frequently re-reading the other novels as well. With strong themes of overcoming pride, preconceived notions, and prejudice, Austen’s impact on Harry Potter can be seen clearly today.

(Hannah Lupi, Rachel Thursby)

Exploring Georgian England

Acknowledgements