Food and Drink

What today might be called “household management” was, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, called “domestic economy” and referred to the connected relationship between the woman as a consumer and a homemaker. Many women in the nineteenth century were taught to chase an ideal of the “economic woman.” She was supposed to be the managerial figurehead of the household, maintaining the wellbeing of its structure and inhabitants with frugalness and efficiency.

The Young Woman’s Companion: The Frugal Housewife... is an example of the synthesis of the conduct book and the cookery book. Published in 1811, as the novel was beginning to replace the conduct book in popularity, this book can be seen as an attempt to revive the genre. With everything from pickle recipes to letter-writing tutorials, the book spans the two genres to create a guide marketed to the “economic” elite woman, with elements of a cookery book.

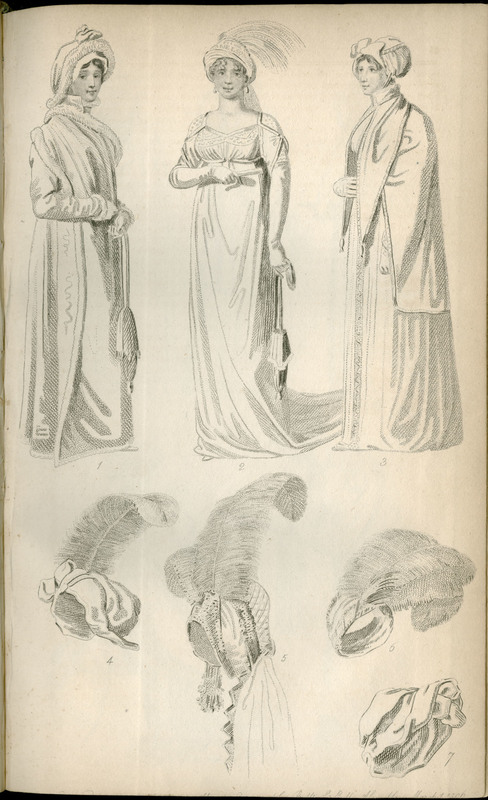

In the majority of Jane Austen’s novels, she structures characters’ introductions around their economic status. The young women in her novels, as a product of their class and era, were constantly navigating through the ‘marriage market’ and searching for a suitable, well-off husband. Instead of supporting the economy in the way we understand it today, Austen’s female characters served as a direct link between consumerism, marriage, and household management. For example, Mrs. Allen in Northanger Abbey pays intense attention to the cost of her outward appearance through the quality of the fabric of her clothes.

(Madeleine Gaudin, Dominic Polsinelli, Stephanie Stoneback)

Elizabeth Raffald

The Experienced English Housekeeper: For the Use and Ease of Ladies, Housekeepers, Cooks, &c., Written Purely From Practice

London: Printed for J. Brambles, A. Meggitt, and J. Waters, by H. Mozley, Gainsborough, 1808

A new edition

Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive

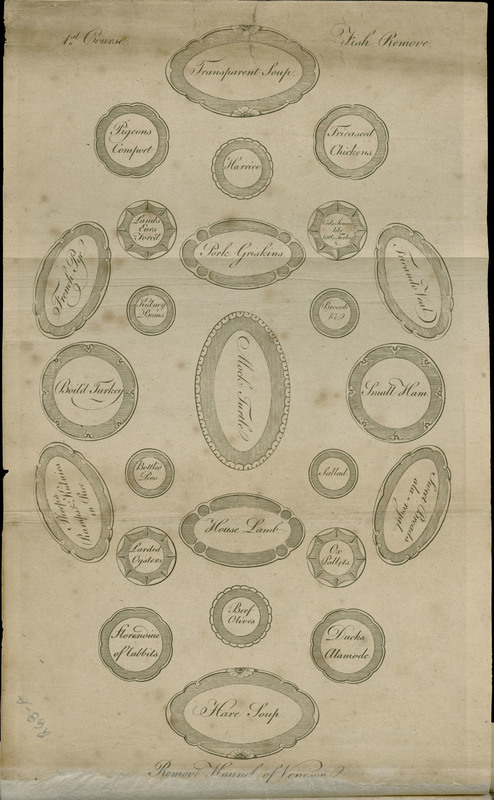

In upper class households, the dinner party was an elaborate production, often consisting of at least ten courses, each with a variety of dishes. Turkey, venison, duck, pheasant, and fish could all be served over the course of one meal along with various fruits and puddings. The most social meals could last three to four hours. Guests of the highest social standing were commonly seated next to each other around the table. These gatherings are common in Austen’s novels, and reflected the status of both those serving and those being served. The image of the table setting helps a modern-day reader understand the magnitude of executing such a dinner party.

Elizabeth Raffald’s instruction manual for housekeepers was initially published in 1769, and enjoyed large popularity in her lifetime. Male cooks were preferred by wealthy households, or at least a woman cook who had been trained beneath a man, so Raffald’s level of training and ability to pass on knowledge is unique in her time. Up until the book’s publishing, many cookbooks published had been written by men, so Raffald’s practical guide by a housekeeper for housekeepers filled a need. She had served in country houses as a housekeeper for fifteen years and her cookbook contains over eight hundred of her own recipes. The book also includes instructions for serving and setting the table, and even a drawing of the stove. Raffald’s inclusion of a diagram of the table is typical of cookery books of the period.

(Emily Fishman, Ingrid Johnson, Lars Johnson)

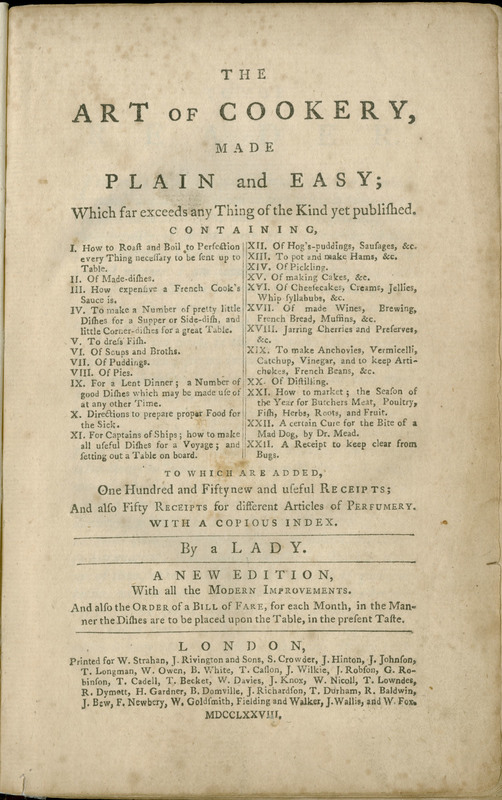

Toward the beginning of the nineteenth century, dining played a large role in the forming and maintaining of social acquaintances. Throughout many of Jane Austen’s novels, groups of individuals connect around a single circular table to engage in conversation, thus exchanging many niceties over food. Instructional books such as Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery... became immensely popular in the preparation of these meals. Although Glasse directs her work at servants in the introduction, middle class families often played an active role in the direction of these recipes. Even though Austen may not have been in the kitchen herself, her interest in exchanging these recipes and cooking tips has been documented in her letters to friend and companion, Martha Lloyd.

Dining in Jane Austen’s novels also held particular importance for her characters, as did simple conversation about food. At various times in Emma, Glasse’s recipes make a featured role in dinner scenes and conversation. “To make different sorts of tarts,” “to bake apples whole,” “to fry eggs,” and “to boil eggs” are all recipes featured in Glasse’s book, and are all foods which hold particular importance in exchanges between the characters in Emma. Baked apples are served to guests, and meals vary from gruel to those of scalloped oysters and chicken. The way a servant cooks eggs and a tart is held as a point of pride during dinner parties and a point of conversation for Mr. Woodhouse, demonstrating the gentry’s close association with the preparation of food

(Amber Mitchell, Natalie Zak)

Fashion and Design

Army and Navy