Highlights from the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection

The University of Michigan Papyrology Collection contains a wide range of papyrus fragments, including personal documents, important Biblical texts, literature, mathematical texts, and even drawings. Some important highlights are shown below.

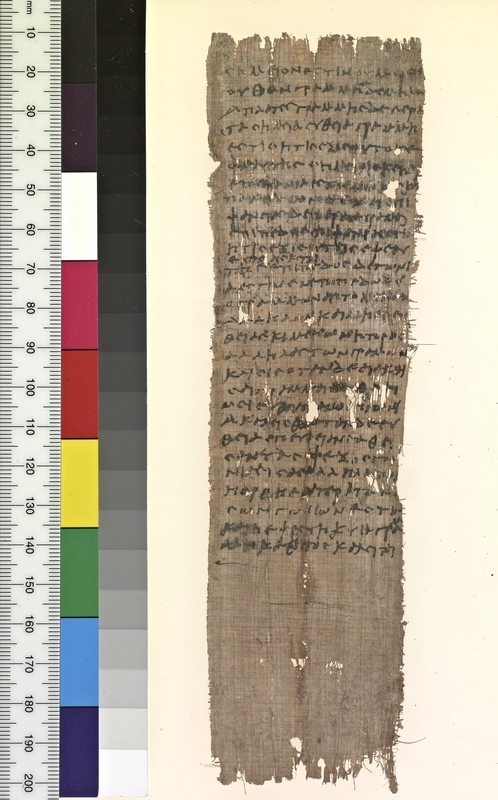

Euclid, Elements I, Definitions 1-10

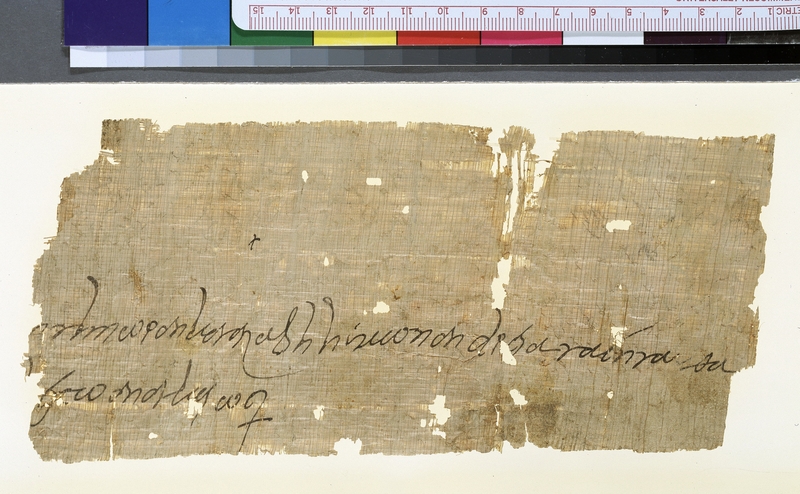

This papyrus contains the first ten definitions from Euclid’s mathematical work Elements, written on the back of a letter (see photograph). Euclid wrote this work around 300 B.C.E. in Alexandria. Soon, it became a foundational treatise in the field of mathematics, particularly in geometry.

The rendering of Euclid’s ideas in this papyrus contains elements from the two traditions that became the primary models for later readings of his work. Discrepancies in this papyrus that scholars once dismissed as errors are now being considered more seriously for their potential to enhance our understanding of the development of the two principal understandings of the Elements.

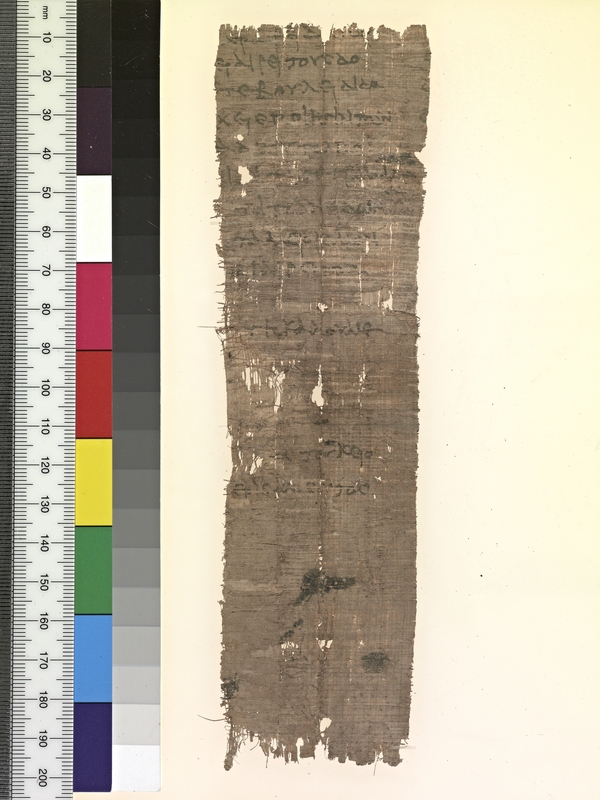

Documentary papyrus

This photograph shows the front of the papyrus containing the fragment of Euclid. Only a few faded lines of text are preserved, but it most likely deals with official or business affairs. Scholars hypothesize that a teacher later took this document — apparently not important anymore — and copied Euclid’s text on the back to use as part of a lesson plan.

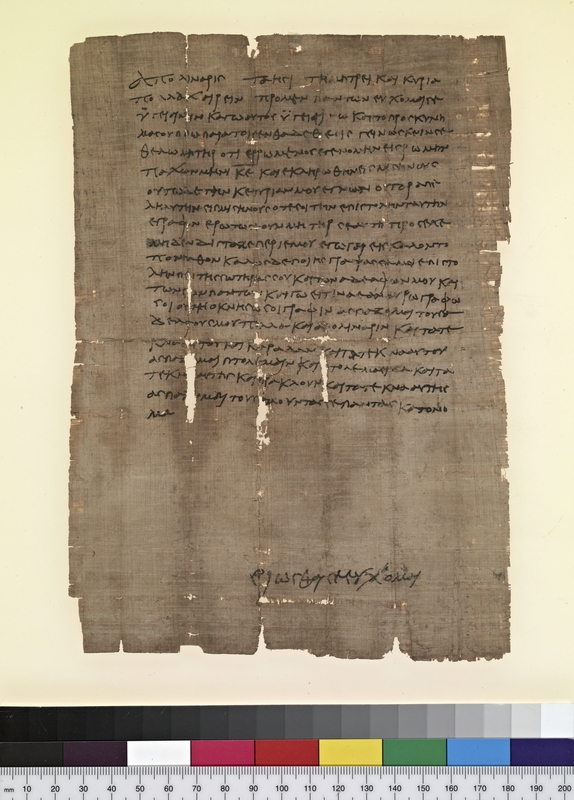

Letter from Apollinarius to his Mother, Taesis

Upon his arrival in Rome, a new recruit in the Roman military sent this letter to his mother in Karanis, Egypt. He wrote that he was preparing to join the navy at Misenum, a large base on the Bay of Naples, Italy. His enthusiastic assurances of safety and ardent promise to keep in touch echo sentiments still used by children today to comfort their concerned mothers. A touch of homesickness may be evident as well in the faithful son’s many greetings to friends and family back home in Karanis, as well as his request that his mother send him frequent letters with news of home.

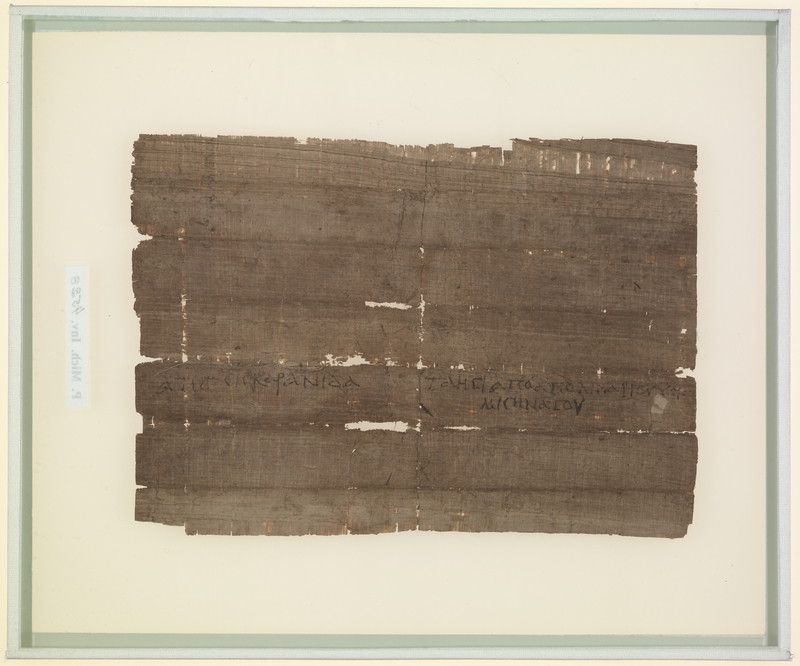

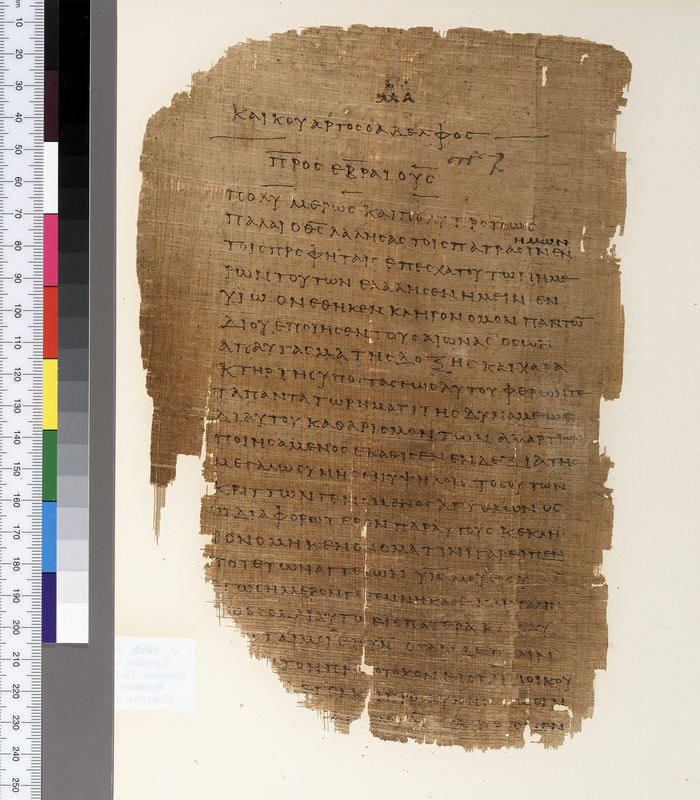

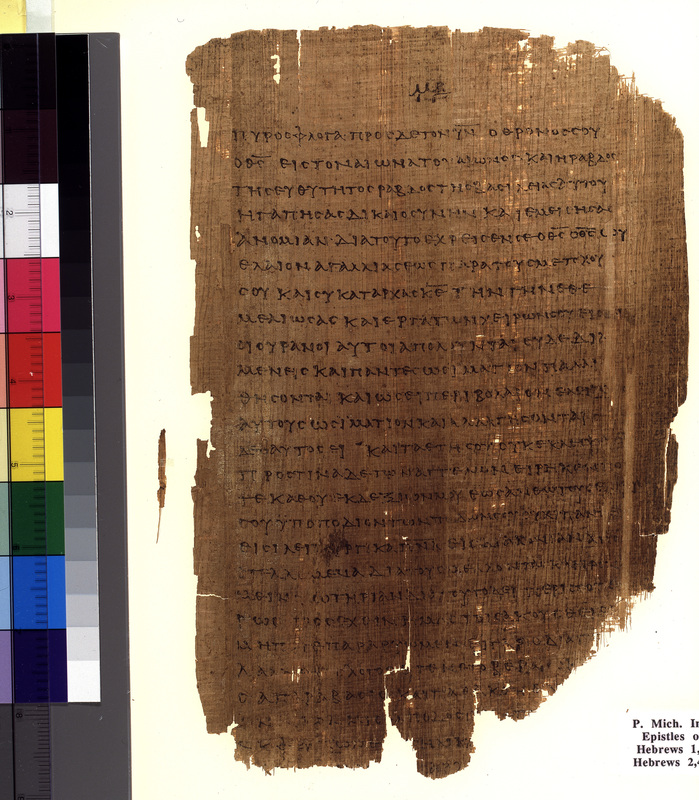

Epistles of St. Paul

These papyri represent two of over two dozen pages from the earliest known manuscript of the Epistles of St. Paul, which has long been a highlight of the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection. The pages were originally bound together in the form of a papyrus codex and thus represent an early stage in the development of the modern book form. The wear and tear that is especially prominent on one side of the bottom of each sheet indicates where readers would have leafed through the pages of the manuscript.

An unusual characteristic of page 41 is the placement of Hebrews directly after Romans, an order different from modern editions of the New Testament and occurring only rarely in other manuscripts. These papyri are valuable to contemporary Biblical scholars who are interested in examining differences between papyrological documents and later medieval editions of the Epistles of St. Paul.

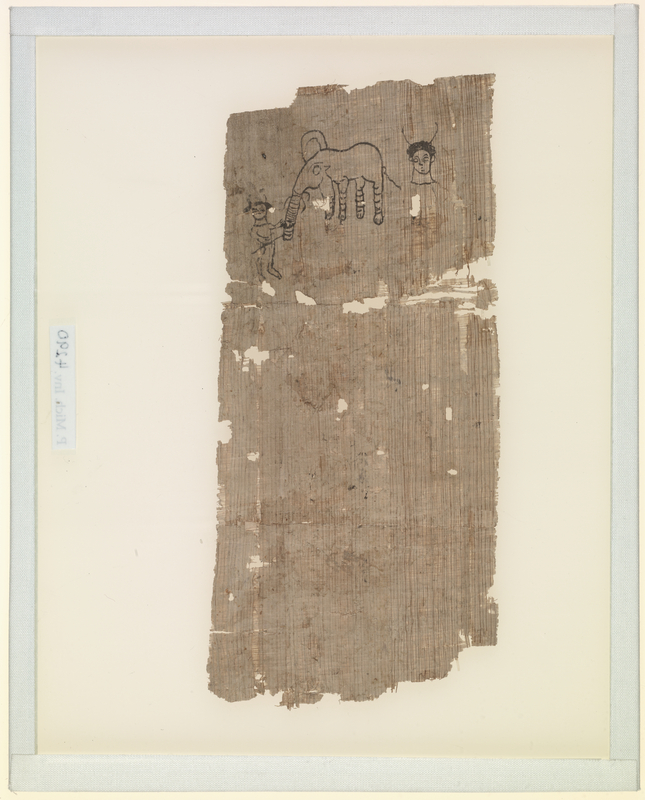

Sketch of an Elephant with Two Figures

This drawing is found on the back of an invitation (see photo), though it is unclear if the sketch is related to the content of the letter or simply a doodle created during a moment of leisure. The unidentified artist depicted an elephant, possibly African, facing a human figure (who may represent an elephant handler) and a relatively large human head. Elephants were not particularly common sights in fifth/sixth century Egypt, but the artist may have seen these animals at a Roman circus. The headdresses worn by both human figures are comparable to those in drawings of Africans and Indians of the same era.

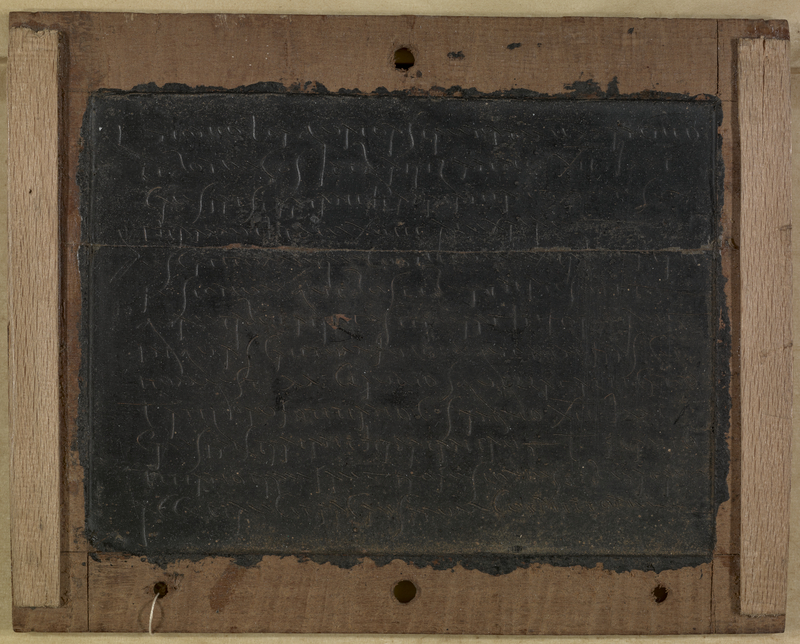

Birth certificate of Herennia Gemella

This pair of wax tablets is an official copy of the birth certificate of a Roman citizen, Herennia Gemella. In Roman Egypt, Roman citizens had to be recorded in Alexandria within a month of birth, and their registration was posted publically in the metropolis as evidence of Roman citizenship. Because Roman citizenship was highly valued as an indication of social status, parents sometimes made their own official copy of their child’s birth certificate to record and preserve the occasion.

The document would have originally been composed on two wax tablets bound in wooden frames sealed shut by the seals of the witnesses — with the text on the inside, so that it could be read only after breaking open the exterior seals. On the exterior of the wooden tablets is another copy of the same text. The entire text is written in Latin, reflecting the citizenship of the child, except for the final line on one of the exterior wooden frames, which includes a Greek transcription of the daughter’s name.

From Trace to Text: Interpreting Papyrus

New Discoveries