From Trace to Text: Interpreting Papyrus

Papyrus fragments go through a number of processes before they can be presented for viewing and study. After excavation, they must go to a conservator who prepares the papyri for study. A papyrologist then transcribes, translates, and interprets the text on the papyri, sometimes with the help of modern technology.

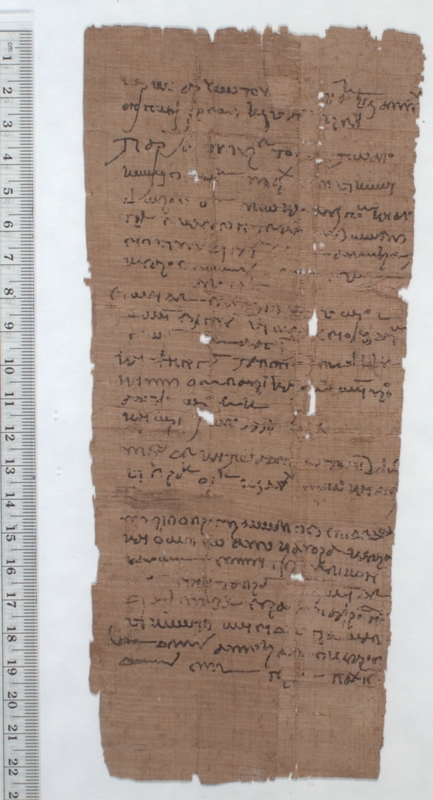

What does a papyrus look like when it is found?

Papyrus documents that come out of the sand of Egypt are often in bad shape, such as the heap of papyri shown here. Having spent on average two-thousand years in the desert sand, many papyri are damaged by time, insects, or humidity. They are often found in places that do not provide optimal conditions to preserve papyrus, such as tombs, rubbish heaps and even, occasionally, ancient mummy casings.

How do you conserve a papyrus?

Papyrus documents need careful attention. Papyrologists and conservators now do most of the restoration and conservation work on the site of the discovery, because the papyri will be stored in a local storage facility in Egypt after the excavation season is over. For papyrus documents that are already in collections, such as here at the University of Michigan, conservation experts sometimes work in special laboratories. Conservation work includes cleaning the papyrus, straightening fibers, and sometimes unrolling a papyrus roll that has survived the ages unopened.

What do papyrologists do?

When the work of the conservator is done, the papyrologist can get to work. Their task is to decipher what is on the papyrus. This is not as simple as it seems, because texts on papyrus documents are written in a variety of handwritings and languages, including Egyptian (in its different scripts), Aramaic, ancient Greek, Latin, and Arabic. Papyrologists often specialize in one or more languages and in either literary or documentary texts.

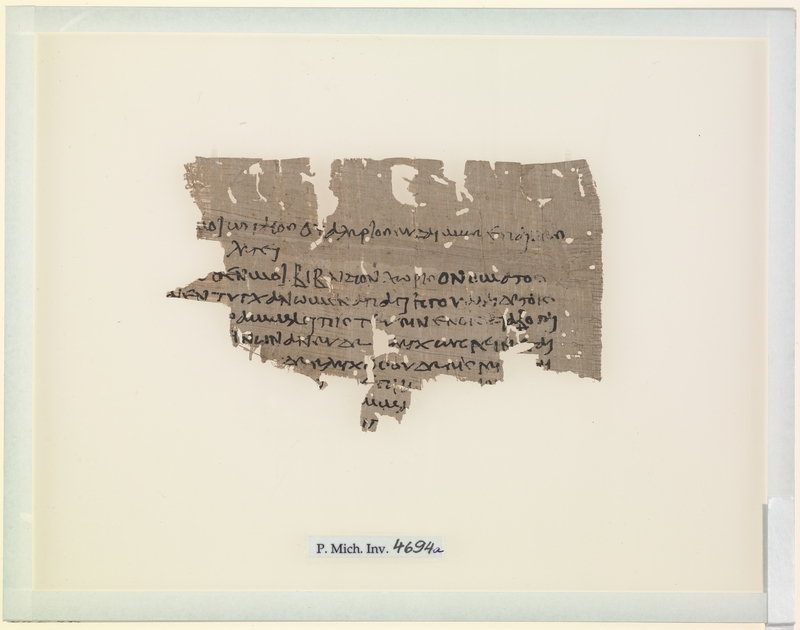

Original Papyrus

This papyrus preserves the beginning of an edict from the Roman official Gaius Valerius Eudaimon. It is directed against people who are making anonymous accusations of some kind.

How do papyrologists communicate their findings?

After transcribing the papyrus, the papyrologist prepares the text for publication. A traditional papyrus publication (“edition”) contains a description of the physical characteristics of the papyrus, an introduction to the importance of the particular document, a transcription of the text, a translation into a modern language, and some explanatory notes on individual words or passages.

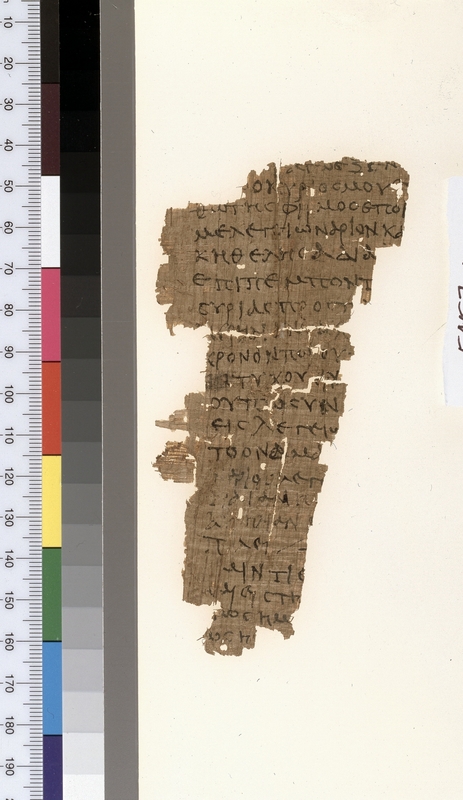

Original Papyrus

This papyrus contains a letter, of which the beginning has not survived. The unidentified sender writes he has just been appointed as a legionary, but is experiencing some difficulties with the appointment. Because the letter was found in Karanis, Egypt, it is likely that the addressee was an inhabitant of that town. The sender was probably stationed near Alexandria.

Are papyrologists ever done with a papyrus text?

Editing papyrus documents is a never-ending effort. The incomplete and damaged state of many papyri leaves ample room for large or small mistakes in the process of reading the texts. Words can be misread, sentences can be misunderstood, interpretations can be wrong. These mistakes may be uncovered by future generations of colleagues, as new texts are published that shed light on old texts.

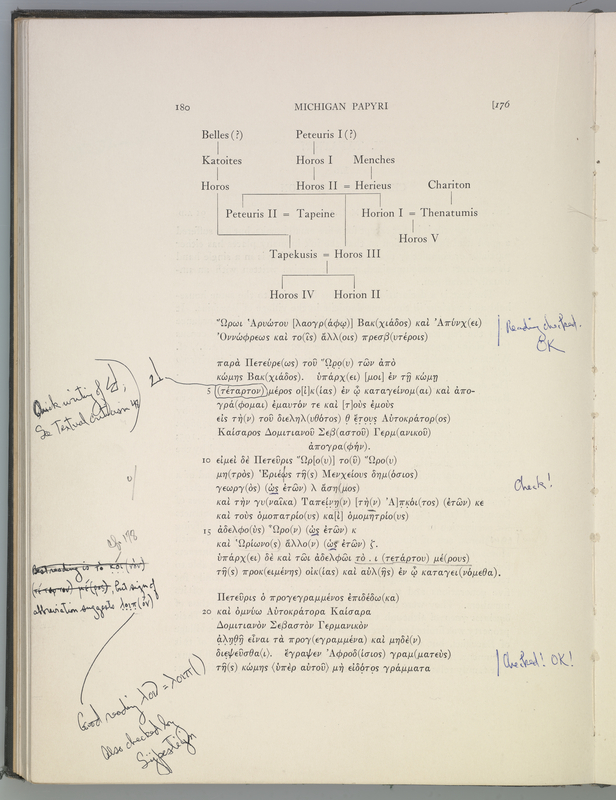

Original Papyrus

This papyrus document contains a census declaration. Peteuris, son of Horos, an inhabitant of the village of Bacchias, registers the members of his household for the Roman census that was held every fourteen years. From the text it appears that Peteuris is living in a house with his wife and two brothers (aged 20 and 7).

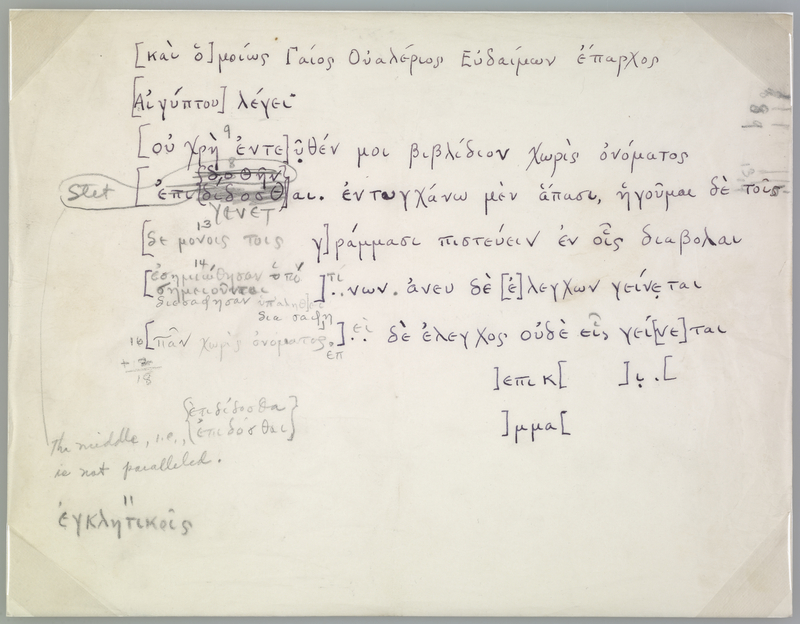

Modern Marginalia

This book, which belonged to Herbert Youtie (1904-1980), contains the first edition of the papyrus document shown here (P.Mich. 176). The pen and pencil marks in the book show that Youtie made several corrections as he looked at the papyrus again. He later published these corrections in papyrological journals, so that they became a part of the scholarly record.

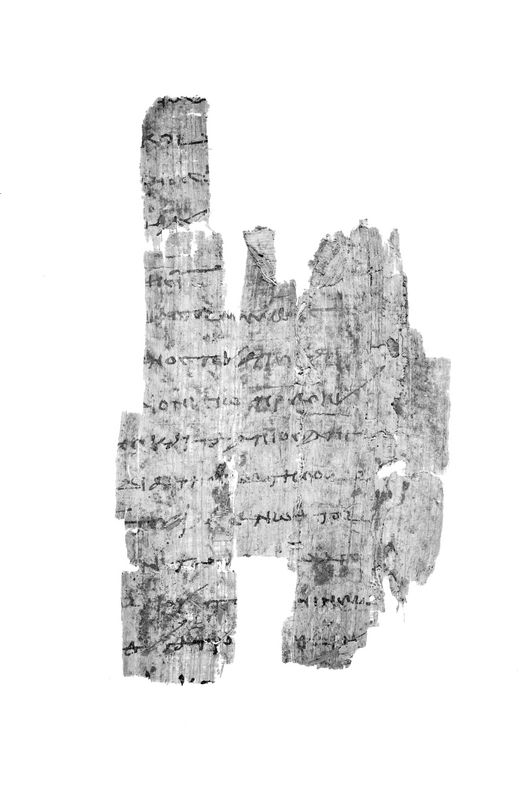

How does modern technology help papyrologists?

Papyrus documents are often difficult to read or even unreadable to the naked eye. Some texts can become legible through infra-red photography. An even more recent technique is multi-spectral analysis, which can make visible traces of writing that have been washed away. Computer scientists are also attempting to virtually “unroll” papyrus rolls with the help of X-ray CT scanning techniques. Unfortunately, these techniques are not yet able to make all types of ink used in antiquity visible.

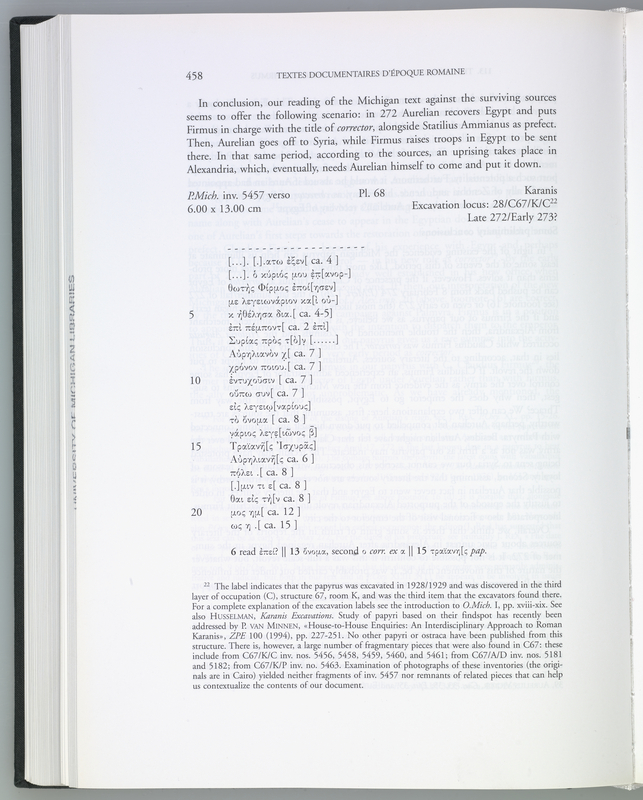

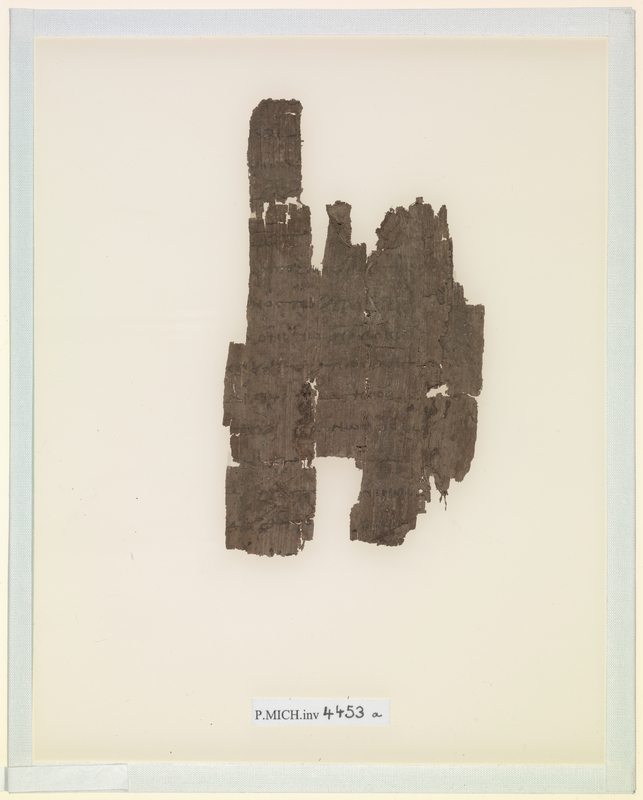

With the Naked Eye

The front of this papyrus possibly shows a list of crops. The back, shown here, contains the remains of either a private letter or a petition. Both sides of the papyrus are very dark, and very few letters can be deciphered.

Highlights from the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection