Dioskoros of Aphrodito

The papyri in the archive of Dioskoros date from the mid VI to the early

VII centuries A.D. They were purchased in 1943 for the University of Michigan

by Mr. Thomas Whittemore. However, the archive of Dioskoros reaches far

beyond the borders of Ann Arbor. Papyri in the collection can be found

in Cairo, Florence, London, Alexandria, Berlin, and elsewhere in America

and Europe. Originally, the archive was discovered at Kom Ishgau, or ancient

Aphrodite in the Antaeopolite nome, in the early part of the 20th

century.

The information that the archive provides us about the ancient city of

Aphrodite

and its inhabitants is invaluable. The village of Aphrodite had previously

paid its taxes directly to the government, without going through the nome

capital, Antaeopolis.

During the sixth century A.D., Aphrodite requested a change from its independent

status in order to protect itself from the growing pressure of tax collectors

in Antaeopolis. The village became directly dependant on the emperor's

house, through his wife Theodora. This is attested in the petition P.

Cair. Masp. III 67283, in which the help of the empress in requested.

Due to the prominent positions that Dioskoros' family held within the

community, they would represent the village to the local and imperial

authorities, serve as witnesses, draft documents for their fellow villagers,

and were often asked to keep these documents. Hence, in the archive of

Dioskoros we find a plethora of documents pertaining to the affairs of

other members in the community, (e.g. P.

Mich. 6902, 6903,

and 6906).

The papyri relate to us the thirty years before the death of Dioskoros'

father, Aurelius Apollos. Our first encounter ,(P. Flor. III 280), with

Apollos is in 514 A.D. as the protokometes, (village headman),

a position that he seems to have recently acquired, ( See J. G. Keenan,

957-63). In 538, we hear of him founding a monastery, and later in 541

A.D. of a trip to Constantinople with his nephew, Victor. His visit to

Constantinople, documented in P. Cair. Masp. II 67126, is believed to

be affiliated with the city of Aphrodite's privileged

tax status or perhaps a religious pilgrimage for Apollos, now a monk,

and his nephew and a priest, Victor.

Like others of his time, Apollos acted as a middleman in leasing out

land from secular, ecclesiastical and monastic landholders in Phthla and

Aphrodite and would proceed to rent these lands out to peasant farmers

at a higher price. This was a highly entrepreneurial activity, from which

many benefited. Aurelius Phoibammon, Apollos' cousin-in-law, and his brother

Besarion, are known to have participated in this business venture. In

fact, one of these lands, which Phoibammon has taken possession of, becomes

the topic of dispute in P.

Mich. 6922.

After the death of his father, Apollos, the archive and all related documents

came into the possession of Dioskoros. Dioskoros is most famous to papyrologists

for his poetry. However, Dioskoros was not only a poet but also a notary,

lawyer, administrator, property owner and more. His first official text

was the petition referred to above, (P. Cair. Masp. III 67283), written

in 547/8, yet his earliest known work was written in 543 A.D.

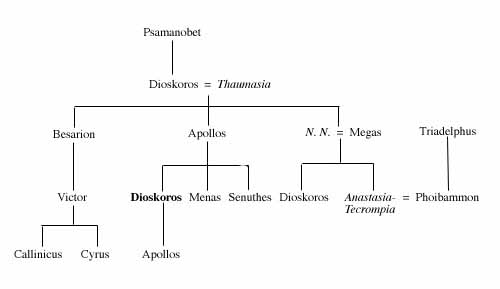

From the archives we are able to learn quite a bit about Dioskoros and

the rest of his family. Dioskoros himself was born sometime around 520

A.D. and he is last attested in the archives in 585 A.D. He was given

his grandfather's name, as was his own son, Apollos. His great grandfather,

however, had an Egyptian name, Psimanobet, meaning "the son of the gooseherd."

As noted by T. Gagos, this does not necessarily insinuate native origins,

but does however rule out the family as belonging to the Greek elite in

Egypt.

The remains of Dioskoros' family tree can be mapped out as follows, (from

T. Gagos, p. 131, fig. 1):

In P.Mich.

6922, mentioned above, several family members come together in order

to resolve a dispute over some land. In this text Apollos, son of Dioskoros,

represents his niece Anastasia alias Tecrompia and her husband Phoibammon.

It appears that the land was previously owned by the parents of Nikantinoos,

who represents the other side of the debate. Nikantinoos' parents had

formerly used this piece of land to secure a loan between the parents

of Iosephios, (the names of his parents have not come down to us), and

themselves, with Iosephios identified as the lender. Both Nikantinoos'

and Iosephios' parents had passed away, thus Nikantinoos inherited the

debt of his parents, and Iosephios the loan contract. However, the land

in dispute was inherited by Nikantinoos' nieces and nephew. Where do Anastasia

and Phoibammon come in? It appears that Nikantinoos' nieces and nephew

unwittingly sold them the land illegally, i.e. while the loan had not

yet been paid off. The outcome of the case is that Nikantinoos must pay

off his parent's debt to Iosephios, thus nullifying any hold he has on

the property and allowing Anastasia and Phoibammon to retain the property.

However, Anastasia and Phoibammon must pay a reimbursement to Nikantinoos,

possibly because they paid less than market value for the property, as

T. Gagos suggests, (see p. 24-5).

Although this document represents an "out of court" settlement, it was

drawn up in Antinoopolis.

This is due to the fact that the courts were located in Antinoopolis,

the nome capital, and if further action had been taken, the dispute would

have been settled in the very building in which the settlement was drawn

up. However, the families of Dioskoros and Nikantinoos decided on the

option of using mediators made up of their peers, that is the adult males

from Aphrodite.

This document, as it would have been included in the papers of Phoibammon,

is just one of the collections of papers that Dioskoros held onto for

friends and family members. For example, P.Mich.

6902 records the sale of a house made by Aurelia Eudoxia, and in 6903

another sale by Aurelia Maria. In these texts, no mention is made of anyone

in the family of Dioskoros. Yet again in P.Mich.

6906 we do not hear of Dioskoros' family in relation to the lease

of a vineyard by Aurelius Menas, son of Psate. Thus they belong to the

archives of others, yet are being held by Dioskoros and his family.

The archive of Dioskoros thus provides us with a window not only to look

into the lives of his family members, but to reconstruct a portion of

the community and ancient city of Aphrodite and its surroundings through

further investigations into the archive. Hierarchies of the elite within

Aphrodite have been drawn based on P. Cair. Masp. III 67283, (see T. Gagos,

p. 10-15); further family trees of fellow townspeople can be mapped out;

explorations into the literary and social climate in Egypt have been based

on the poetry and documents in the Dioskoros archive, (see L.S.B. MacCoull,

Dioscouros of Aphrodito: His Work and His World (Berkeley:

1988), A. Cameron, "Wandering Poets: A Literary Movement in Byzantine

Egypt," Historia 14 (1965):470-509). Thus, the archive of Dioskoros

leaves us with much more to be discovered not only about the members of

his own family, but the inhabitants of Aphrodite, the city itself, and

Egypt at large.

For a complete list of papyri in the Dioskoros Archive at the University

of Michigan, click here.

More papyri in the Dioskoros archive can be found on the Heidelberg

website by entering Dioskoros into the Bemerkungen field of the search

engine. (Note: not all documents that appear are included in the Dioskoros

archive).

Return to Snapshots of Daily

Life

Bibliography

-

T. Gagos, Settling a Dispute, (Ann Arbor: 1994), University

of Michigan Press.

-

J. G. Keenan, "Aurelius Apollos and the Aphrodite Village Elite,"

Atti del XVII Congresso Internazionale di Papirologia, Vol.

3 (Napoli: 1984): 957-63.

-

P. J. Sijpesteijn, The Aphrodite Papyri in the University of Michigan

Papyrus Collection, (Zutphen: 1977), Terra Publishing Co.

|