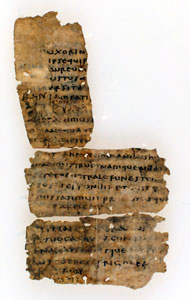

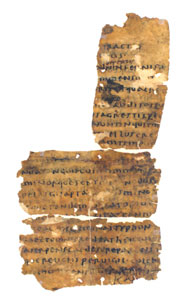

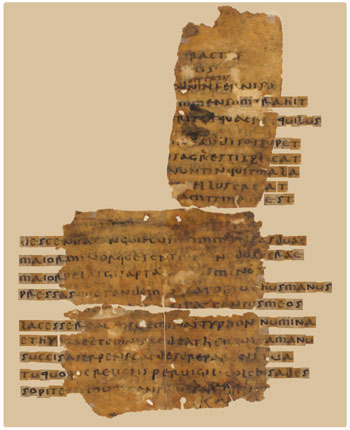

The Medea: IntroductionThis learning resource is part of the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection's series Reading the Papyri, which aims to provide younger classics students the opportunity to study ancient texts via the world wide web. The pages contained in this section cover a fragmentary leaf from a codex containing Seneca's tragedy, Medea, which belongs to the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection. The FragmentsThe fragments form part of inventory number 4969, and this piece has a rather interesting history. These fragments come from a fourth century parchment codex of the Medea which was eventually recycled into a tenth century Coptic codex. (see image below)

The piece consists of three fragments of roughly equal size (a fourth is missing). These fragments were cut from the original leaf and used to reinforce the binding of the Coptic codex; the pinholes visible in each fragment show where the binding was sewn together. As is often the case in papyrology, this text has survived due to no more than sheer luck. The fragments were recognized as Latin and published by Gregg Schwendner and Donka Markus in 1997 (ZPE 117 pp. 73-80). More information about this text is available online via the APIS database: P.Mich.Inv. 4969 PalaeographyThis text is written in a half-uncial script, which uses letter shapes which are similar to a combination of lowercase and uppercase letters that we still use today. You will probably recognize most of the letters without much difficulty. Below is a table showing the alphabet used by the scribe who wrote the Medea codex. Briefly familiarize yourself with the letter shapes. Do they look like capital letters or lowercase letters? Are any of the letter shapes particularly strange? What letters are missing, compared to the English alphabet?

The letters k and z were part of the Latin alphabet by the 4th century, but neither are attested in this small fragment, since neither letter was especially common. The letters w, u, and j do not exist in the Latin alphabet. The TextThe text consists of several lines from Seneca's tragedy, Medea. This complete text of this play is known from other manuscripts, and the fragments can be identified as containing the continouous verses 663-704 (663-683 on the recto, 684-704 on the verso). Using the alphabet above to represent the average size of the letters, we can reconstruct the lost portions of the lines to give an idea of the original dimensions of the leaf.

Based on this type of estimation, the original size of the page was likely around 12 by 18 cm. The image above gives an idea of how much of the page has been lost. Since the Medea was written in verse, we expect that the left margin should be straight, while the right margin will be irregular, varying with the length of each line. It is reassuring that our reconstruction shows the same properties as we expect. Usefulness of the TextSince the full text of the Medea is already known from several other sources, what is to be gained from a short, fragmentary text such as this? As you may already know, most of the classical literature which survives today was preserved in medieval manuscripts. However, different manuscripts of the same work often give different readings, and the goal of the modern editor is to reconstruct the version of the text which is closest to what was originally written by the author. This leaf, although it is short and fragmentary, can help with that goal, since its fourth century date is earlier than the medieval manuscripts, and thus closer in time to the original composition. In fact, there are several errors and corrections in this text which have been useful to scholars. This text is also useful to us because it provides an example of a Latin book hand which is very easy for a modern audience to read. Latin texts from this time period are rare; since most of the papyri which survive today come from the desert regions of Egypt, they are mostly in Greek or Egyptian, not Latin. Most of the Latin texts which do survive are government or military documents, which are written in a cursive script that is difficult to decipher. A book hand such as this is an excellent place for the novice to begin his study of ancient manuscripts. In the next section, you will have the opportunity to look closely at several lines from this text and try to read a bit of it for yourself. |

| Copyright 2004 The Regents of the University

of Michigan. Reading the Papyri is produced by the University of Michigan Papyrus Collection These pages designed and written by Terrence Szymanski. email: papywebmaster@umich.edu |