India Engages the Pandemic

The Indian subcontinent has long been regarded as the probable place where smallpox originated. (Fenner 712) The disease was described in early Indian writings (1500 BCE) and enshrined in Hindu religious beliefs where it has its own deity, Shitala, the “cooling mother”, to which many shrines are devoted.

Smallpox in India, pre-1972

In the early 1960s, India accounted for nearly 60 percent of the reported smallpox cases in the world. (Tucker 90) Because of the stigma and social isolation associated with the disease, numerous cases went unreported. Of greater concern was that particular strain of smallpox found in India was far more deadly than the strains found in West Africa. In response to the situation, in 1962 the government of India launched the National Smallpox Eradication Program (NSEP) with a focus on mass vaccination of the population. It poured money into the vaccine manufacturing industry and hired healthcare workers to perform inoculations. By 1966 approximatively 60 million primary vaccinations and 440 million re-vaccinations were performed. (International Smallpox Assessment Commission 3-5) However, by 1967, it was clear to everyone that the campaign was unsuccessful; the number of smallpox cases in India was increasing.

Several reasons were identified for the failure. One of the greatest logistical reasons was the sheer number of people in the country who were mobile, whether due to political or ethnic tensions, economic needs, or education. This was complicated by individual reluctance and refusal to participate in the vaccination programs due to distrust or religious reasons. Other barriers were administrative: no one wanted to admit that a smallpox outbreak had occurred because of economic impacts. In addition, the type of vaccine that was used -- a liquid that deteriorated in the heat -- and the method of vaccination -- via a painful rotary lancet -- meant there were insufficient supplies coupled with fear of the innoculation process.

In September 1970, on the basis of recommendations of an assessment team, a Plan of Operation was signed by the Government of India and the World Health Organization (WHO). The following year, four WHO medical officers arrived in India in 1971 to spearhead the revised eradication campaign.

Challenges of mass vaccination

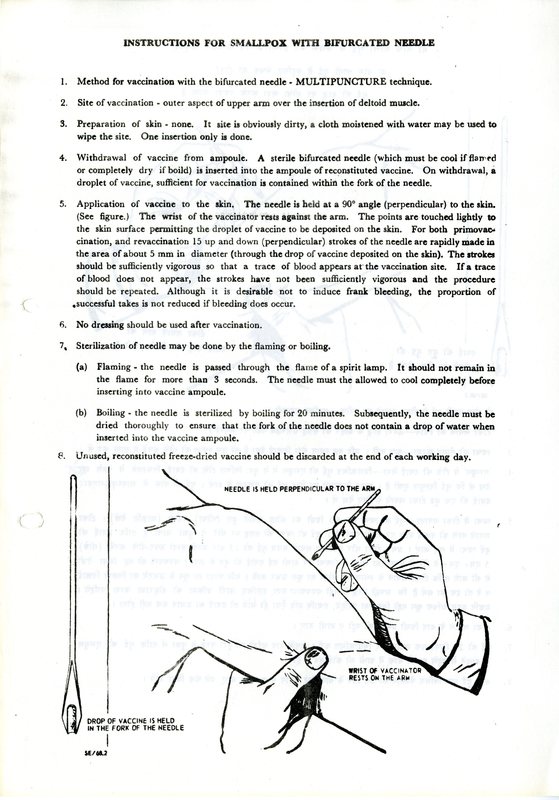

One of the barriers to the successful implementation of the National Smallpox Eradication Program was the quality of the vaccine and the method of delivery. Because of the World Health Organization’s partnership, India was able to acquire higher quality freeze-dried vaccines. Concurrently, the quality of vaccine manufactured within India also improved.

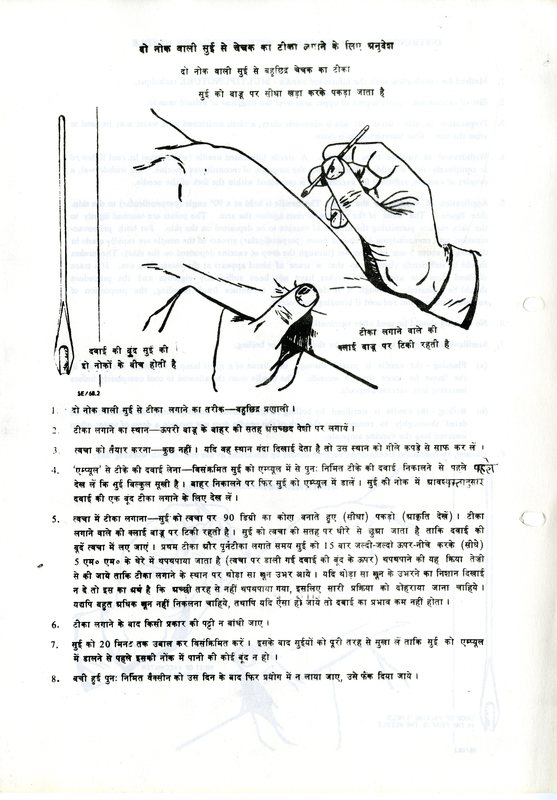

More problematic was the method of vaccination. Prior to 1969, the standard method of smallpox vaccination was to place a drop of vaccine on the patient’s arm and press it into the skin with a single-point needle. This process was repeated five times for a primary vaccination and fifteen times for a revaccination. Much vaccine was wasted and it was difficult for workers to perform correctly. The jet injector was an improvement over the single-point needle and didn’t require electricity. However, the device required frequent maintenance and was prone to breakdown in the field. (Tucker 71)

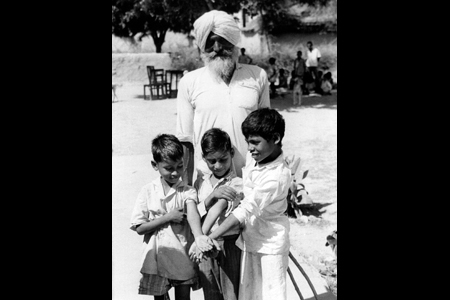

The introduction of a multiple puncture technique, utilizing a bifurcated needle, had immediate positive consequences. The bifurcated needle was a cheaper and easier method of delivery. Healthcare workers needed minimal training. It was also less painful and less traumatic for the patients.

Aside from vaccine quality and the use of bifurcated needles, India had another barrier to successful mass vaccination. In most countries, vaccinating 80 percent of the population over a five-year period was considered sufficient to interrupt smallpox transmission. (Tucker 75) However, in densely populated countries such as India, the large number of births every year (25 million new Indian babies) made this target impractical. Mass vaccination could only reduce the incidence of smallpox; it couldn’t contain it. A new strategy was needed to augment the vaccination efforts: the “surveillance-containment” search.

Surveillance-containment searching

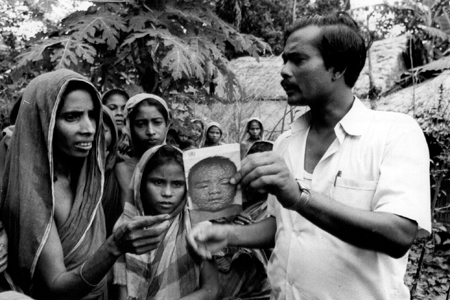

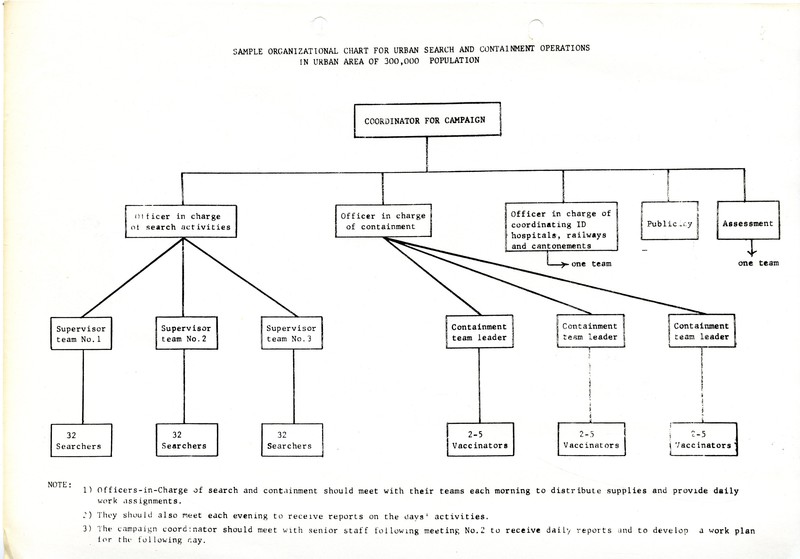

The strategy of “surveillance-containment” was simple in design. Teams of healthcare workers would actively seek out (i.e., search) for all potential cases of smallpox as quickly as possible. The affected individuals and their families or neighbours would be immediately isolated and vaccinated to prevent the further transmission of smallpox. This emphasis on active searches and detection and the containment of outbreaks was essential to eliminate infection foci.

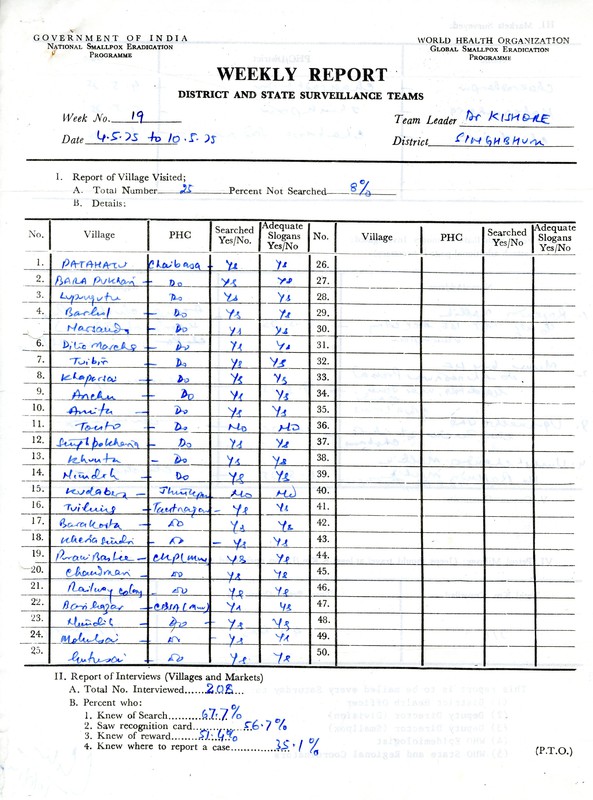

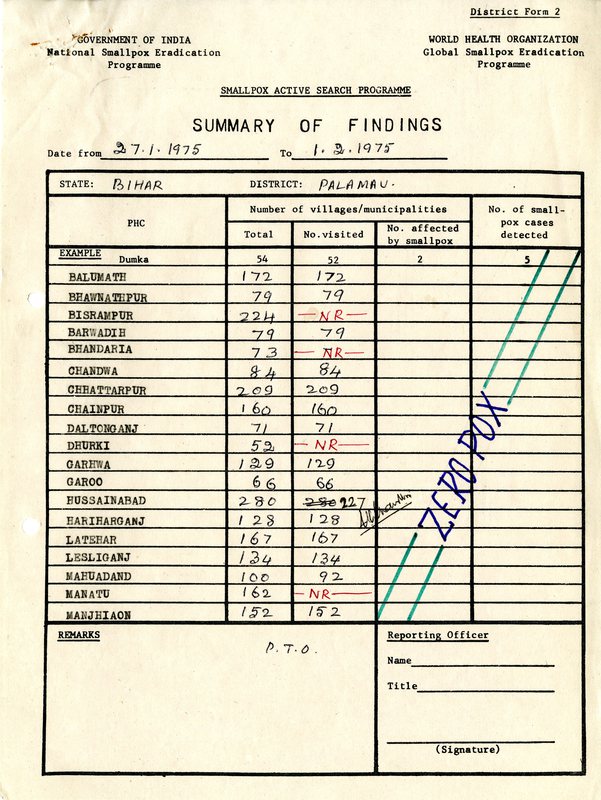

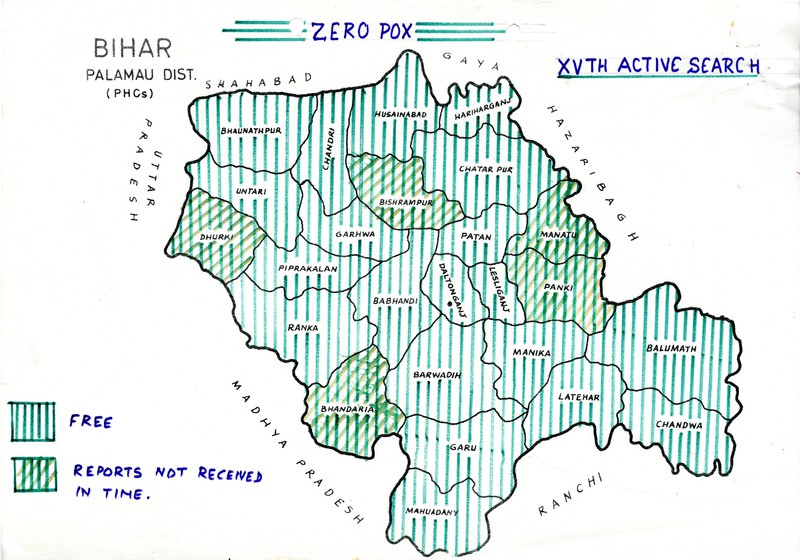

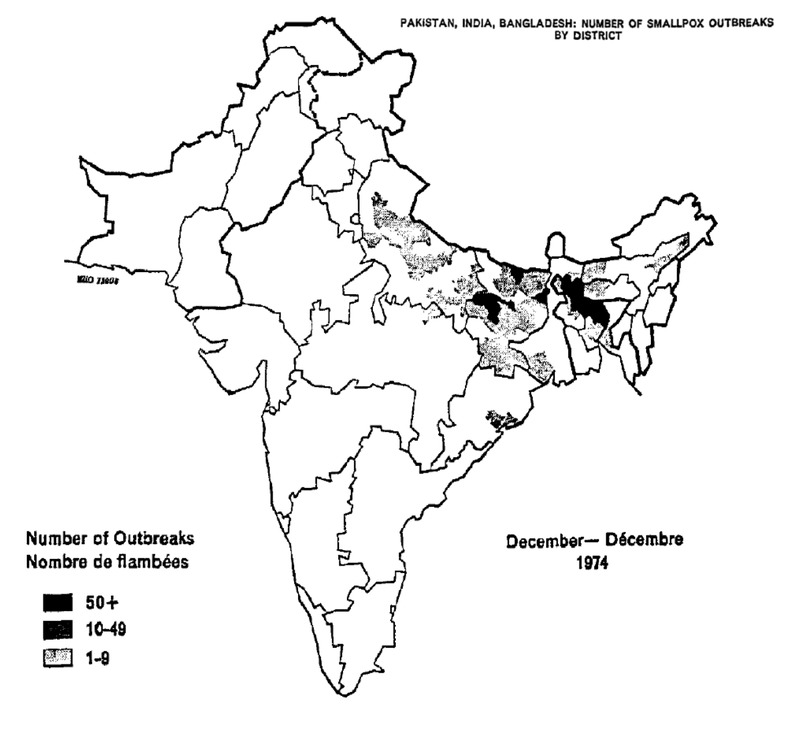

The new method of active searches was implemented throughout India. By late 1974, the scale was enormous:

During a six-day period each month, health workers visited every one of the country’s 100 million households. Supervised by about fifty international advisors and an equal number of Indian officials, some thirty-three thousand district health personnel and more than 100,000 additional field workers conducted house-to-house searches in a total of 575,721 villages and 2,641 cities. (Tucker 108)

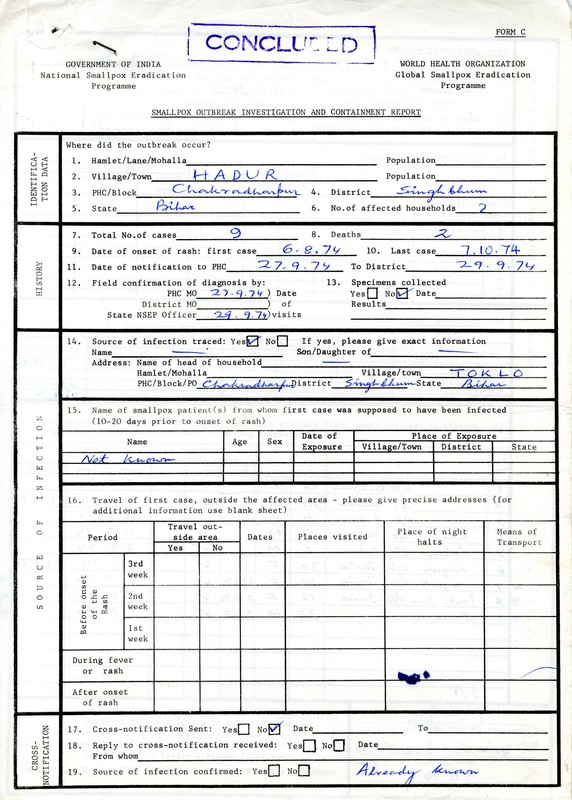

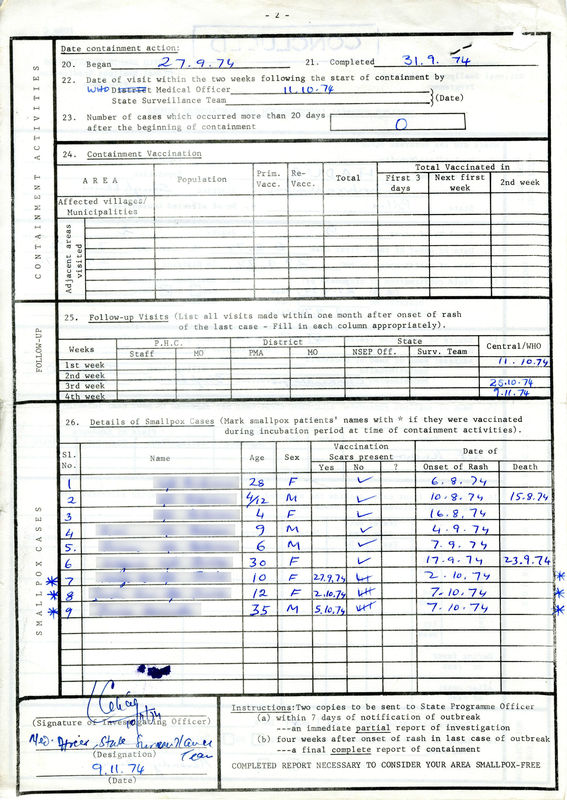

Surveillance-containment was data-driven and data-heavy. The documents that the health workers and epidemiologists had to complete in the field were abundant and various. They had to be submitted promptly and then quickly analyzed. This type of record-keeping was tedious but necessary. It is estimated that each nationwide search of smallpox consumed about eight tons of paper forms. (Tucker 108)

Training the health workers

The World Health Organization (WHO) country office in India was located in New Delhi. Dr. Nicole Grasset, a French-Swiss virologist and epidemiologist, was the head of the WHO team. Three other members completed the team: Dr. Zdeno Jezek, a Czech epidemiologist, Dr. William H. Foege, an American physician, and Dr. Lawrence Brilliant, a graduate of the University of Michigan.

The WHO team was augmented by many others: Indian government officials (including Dr. P. Diesh, the Assistant Secretary for Health and Dr. M. I. D. Sharma, Head of the National Institute of Communicable Diseases), Indian health experts, international advisers, and health workers.

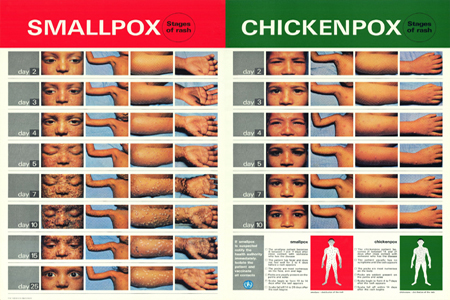

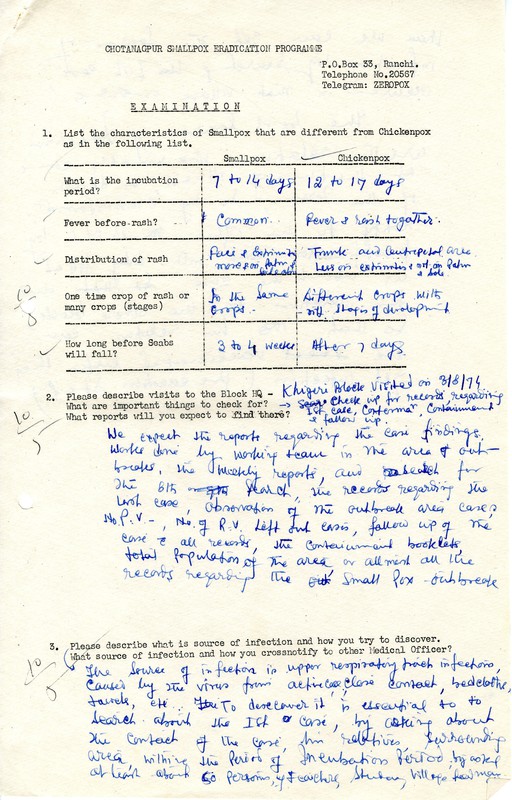

Newly recruited staff were given a “Briefing Packet” with an overview of the smallpox situation in India (incidence, severity, etc.) and other preparatory information they would need for field work. This included illustrative material showing the stages of rash for smallpox and chickenpox. They were also expected to read and be familiar with guides such as the WHO Handbook for Smallpox Eradication and A Guide to the Clinical Diagnosis of Smallpox.

Part of the supervisor training included group exercises in which participants learned to identify the circumstances and problems of smallpox outbreaks, the importance of tracing the source of infections, and the need to initiate containment measures at each stage of the investigation.

A written final exam was given at the end of training for all new staff.

Finding every case

The Government of India threw its full weight behind the National Smallpox Eradication Program. In urban areas, a carefully organized massive publicity campaign was an essential component several days in advance of World Health Organization team visits.

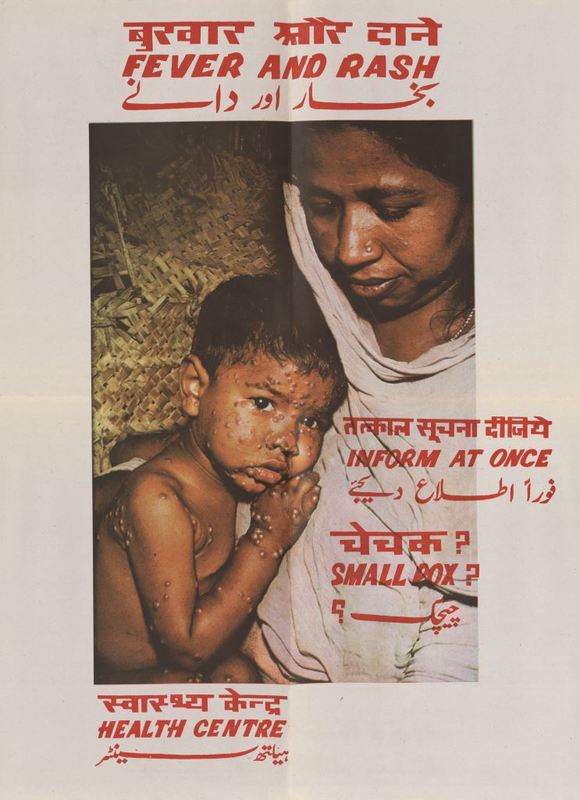

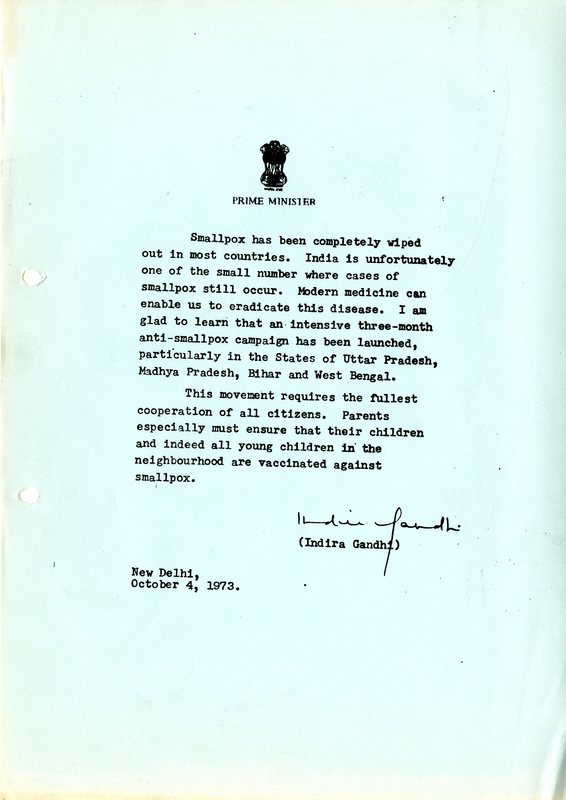

Posters were created in native languages which encouraged vaccinations, especially of young children. Even Prime Minister Indira Ghandhi was involved in the marketing effort. She sent announcements to several Indian states exhorting their citizens to cooperate with the programs.

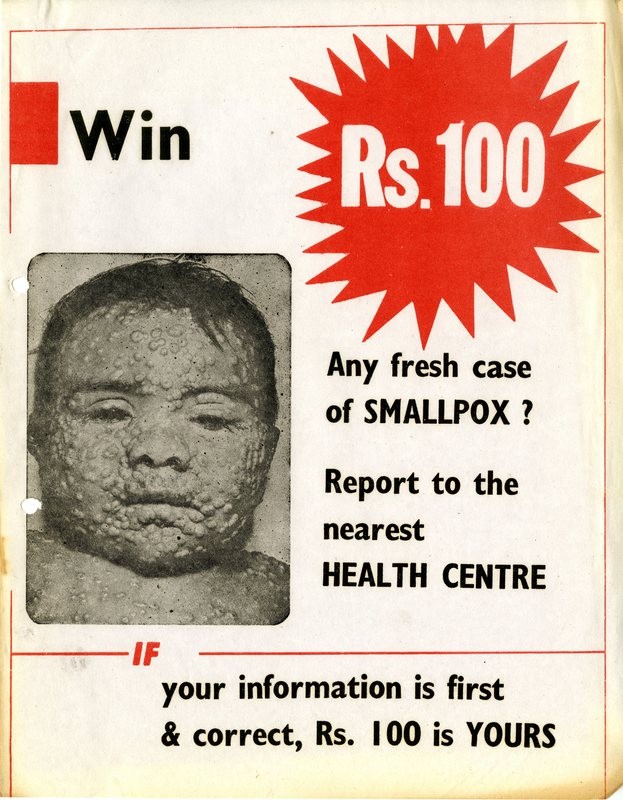

Perhaps the most unusual publicity method was the reward of 100 rupees ($12) for the report of any fresh smallpox case. The reward was gradually increased as the incidence of smallpox declined. It was highly effective. Eleven percent of smallpox outbreaks were reported by the general public in 1975, compared with only 2.6 percent in 1973. The rewards were widely publicized using loudspeakers, radio and television announcements, posters, newspaper advertisements, and writing on public walls. However, word of mouth communication continued to remain the most effective means to find new cases.

Zero smallpox

In May 1975, the very last case of smallpox was found in India. For the next two years, searches and active surveillance were continued to ensure there were no hidden smallpox pockets. In this phase of the program, data was collected on the various rashes that health workers encountered in their field work. This led to the development of additional reporting documents, such as the Fever and Rash Outbreak Surveillance. This form required that each health worker report all cases of fever with rash, cases of and deaths due to chickenpox as well as cases of suspected smallpox.

From March to November 1976, 110 million households -- in more than half a million Indian villages and in 260 urban areas -- were searched for new smallpox cases. (International Smallpox Assessment Commission 5) Only cases of chickenpox were found.

In December 1976 and January 1977, a National Commission (including World Health Organization epidemiologists) visited all States and Union Territories of India, except the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and scrutinized program activities.

A few months later, in April 1977, the International Commission for the Assessment of Eradication of Smallpox in India visited the country, conducting its own evaluations in the field as well as reviewing the documentary evidence provided by the country.

The International Commission finally certified that India was free of smallpox. Two years later, in December 1979, the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication declared that smallpox had been eradicated from the planet.

Chronology of the eradication campaign

1972-1973: Intensive campaign in endemic Indian states

October 1972: The Indian states are divided into two categories: endemic and non-endemic. The endemic states receive the highest priority and the majority of available resources. State Surveillance Teams are created in urgent areas.

November 1972: The final phase of the Global Smallpox Eradication Programme is announced. In India, the target is to reduced the incidence of smallpox incidence to zero during the course of the next two smallpox seasons.

June - December 1973: A special intensified campaign is launched in June. The first phase takes place in July and August in the urban areas. The second phase, occurs from September to December. The country-wide second phase has a special emphasis on the four major endemic states: Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal.

1974: Further intensification and expansion of the program.

January 1974: The Direction-General of the World Health Organization (WHO) agrees to make available $900,000 to augment existing resources. More WHO epidemiologists are deployed in India. During 1974, at any given time, approximately 100 national and international epidemiologists are working in the field, primarily in the heavily affected areas.

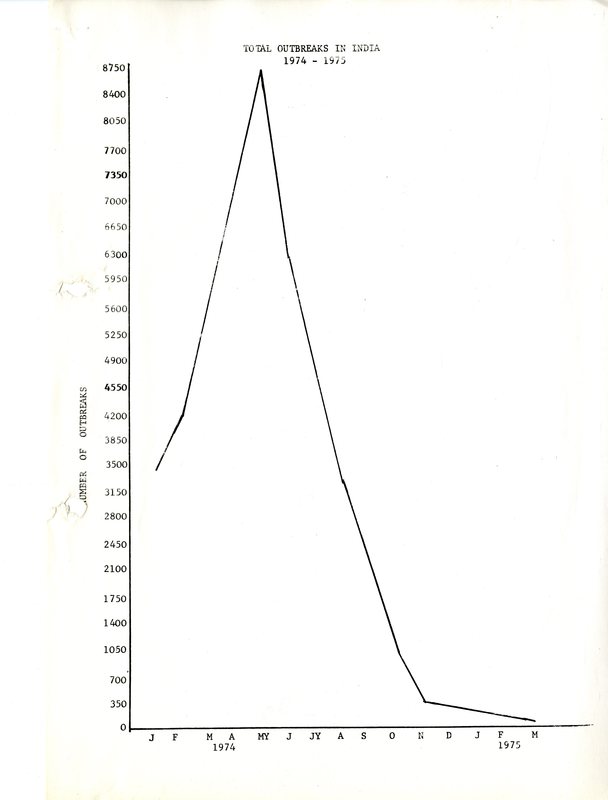

May 1974: The number of smallpox outbreaks peaks with 11,000 new cases reported in a single week.

January 1975: Launch of Operation Smallpox “Target Zero”. Containment of all suspected smallpox cases and chickenpox deaths is undertaken pending definitive diagnoses.

7 April 1975: The theme of World Health Day, “Smallpox - Point of No Return” coincides with an all-India search operation that lasts until 14 April 1975.

May 24, 1975: The last known Indian smallpox patient, a 30-year-old female, is identified.

July 5, 1975: An independent assessment report proclaims that there is no evidence of smallpox after 5 July 1975.

April 1977: Two year search and active surveillance activities confirm that India is free of smallpox.

December 1979: Smallpox is officially eradicated from the planet.

The World of Smallpox

About this Exhibit