Group of Native American Chiefs

This Great Native American Chiefs online exhibit was put together as part of a University of Michigan Library diversity goal. The exhibit creators both have a strong interest in Native American history and culture. They feel that Native Americans have been misunderstood, and that their history has not always been accurately written about in history books. This exhibit is about reaching out to an audience which has an interest in Native Americans, and learning about their existence, culture and history. There are some interesting stories told here, and many more to tell.

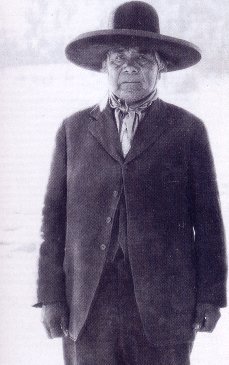

Geronimo (aka Goyathlay)

Chief: Geronimo (Bedonkohe Apache Leader: aka Goyathlay)

Born: June 16, 1829 near Turkey Creek (Gila River), Apache land contested by Mexico, and currently known as New Mexico

Died: February 17, 1909 Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Nationality: Apache

Geronimo was an Apache leader who belonged to the Bedonkohe band of the Chiricahua Apache tribe. He was not considered a chief among the Apache people, but was known as an infamous leader with a warrior spirit that conducted raids and warfare. Geronimo was a symbol of Native American resistance to both the United States and Mexican military. He acquired a reputation as being a fearless fighter who wreaked havoc and vengeance on Mexican troops, because they had murdered his entire family that included his wife, children and mother.

Many of Geronimo’s raids and combats were in the period of the Apache-American conflict that generated from white settlers occupying on Apache lands after the war ended with Mexico in 1848. Initially the warfare began with the older Apache-Mexican conflict, and then the Apache-American conflict. During the years of 1850 to 1886 raids and retaliation had become the normal way life between the Apaches and Mexicans and later Apaches and Americans. Raids consisted of stealing livestock for economic purposes, and the capture and killing of victims from all sides. Geronimo established a strong resistance to his many enemies that lasted for over 30 years. His relentless fighting power earned him notoriety of the worst kind among some of his own people the Chiricahua tribe, and also Mexican and US military.

Geronimo eventually did surrender in 1886, and was held prisoner of war in camps located in Florida, Alabama and lastly Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In his later years Geronimo converted to Christianity, because he thought it was a better religion than his own. He also sold autographed photos of himself, and had the honor of riding on a horse in President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade in 1905. Geronimo was never allowed to return to his tribe or homeland, and died at the hospital in Fort Sill in 1909. His legacy lived on because in 2011 U.S. military that killed Osama Bin Laden was code-named Geronimo.

Resources about Geronimo:

Geronimo. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 27, 2017 from Wikipedia.

Utley, Robert M. Geronimo New Haven, Yale University Press, 2012.

Angie Debo. Geronimo: the man, his time, his place. Norman University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

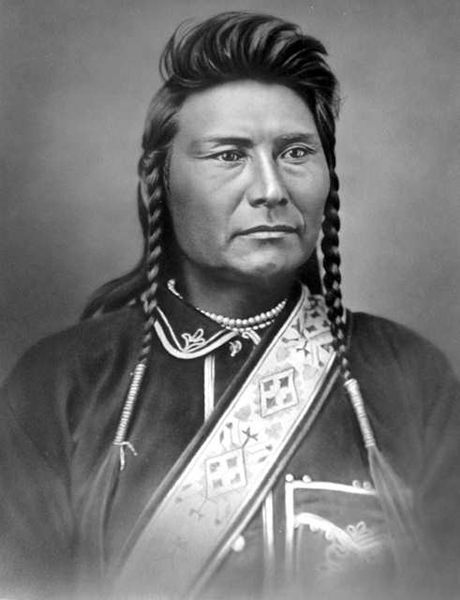

Chief Joseph (aka Heinmot Tooyalakekt)

Chief: Chief Joseph (aka Heinmot Tooyalakekt)

Born: March 3rd, 1840 Wallowa Valley, Oregon

Died: September 21st. 1904 Colville Indian Reservation, Washington

Nationality: Nez Perce

Chief Joseph was a Nez Perce leader who led his tribe called the Wallowa band of Nez Perce through a treacherous time in United States history. These indigenous people were natives to the Wallowa Valley in Oregon. Chief Joseph was a powerful advocate for his people’s rights to remain on their homeland. In 1877 the Nez Perce tribe was forcibly removed from their native land by the United States government. The Nez Perce were given 30 day notice to leave their homeland. At first the Nez Perce people resisted removal, and this resulted in a series of violent events. They were ordered to relocate to a reservation in Lapwai, Idaho which resulted into the Nez Perce War.

In the Nez Perce War Chief Joseph led a couple hundred of warriors, and many women and children eluding United States troops over a 1,300 mile stretch. In a 3 month period the Nez Perce battled their way across the state of Oregon, and all the way to Montana. The tribe first attempted to settle with the Crow in Montana, but the Crow natives refused to help them. Chief Joseph and his people then headed North in hopes of taking refuge with the Lakota tribe that was led by Sitting Bull. The Nez Perce were skillful warriors in the battlefield which earned them great respect and admiration among the opposing cavalry, and the general public. In the fall of 1877 after a long and brutal battle Chief Joseph and his band surrendered in Montana only 40 miles away from the Canadian border which would have led them to freedom. However along the way many of the Nez Perce had either froze to death, starved, or died of disease including five of Chief Joseph’s children.

After the war Chief Joseph was never allowed to return home. In 1885 the Nez Perce and their fearless chief were escorted to Washington so they could settle on the Colville Indian Reservation far away from their original homeland and people in Idaho. In Chief Joseph’s final years he spoke about the cruelty that his people endured from the United States government. His hope was that one day there would be equality for everyone including Native Americans. Chief Joseph died of natural causes in 1904, and is buried in Nespelem, Washington.

Resources about Chief Joseph:

Chief Joseph. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 27, 2017 from Wikipedia.

Davis, Russell and Ashabranner, Brent K. Chief Joseph: war chief of the Nez Perce. New York, McGraw Hill. 1962.

Moulton, Candy Vyvey. Chief Joseph: guardian of the people. New York, Forge. 2005.

Metacomet (aka King Philip)

Chief: Metacomet (aka King Philip)

Born: c.1638 in Massachusetts

Died: August 12, 1676 in the Miery Swamp near Mount Hope in Bristol, Rhode Island

Nationality: Wampanoag

Metacomet was a Wampanoag whose tribe sought to live in harmony with the colonists at first. He became sachem (chief) in 1662, after the deaths of his father and older brother. As a leader he took the lead in his tribe’s trade with the colonists. In time, he took the name King Philip to honor the relations between the colonists and his father and even purchased European style apparel in Boston. As sachem for several years, Metacomet witnessed increased contact and encroachment by white settlers. Much of this contact resulted in humiliations of his people. He is known for King Philip’s War (1675-1678.)

The expansion of the colonies pushed the Native American tribes further west at the same time, the Iroquois Confederation was fighting neighboring tribes in the Beaver Wars encroaching into his territory. Major concessions were forced upon Metacomet’s tribe in 1671 by the colonial leaders of the Plymouth Colony. Open hostilities broke out in 1675, leading to King Philip’s War. The ultimate goal of the Native Americans was to stop Puritan expansion. The conflict lasted until 1678. Metacomet was assassinated on August 12, 1676 by an Native American named John Alderman. Afterwards, his wife and son were sold to Bermuda as slaves.

Resources about Metacomet (King Philip):

Metacomet. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Stratton, Billy J. Buried in Shades of Night: contested voices, Indian captivity, and the Legacy of King Philip’s War. Tucson, The University of Arizona Press, 2013.

Warren, Jason W. Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in the great Narragansett War, 1675-1676. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

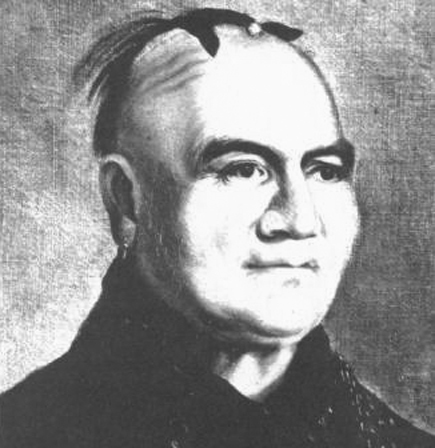

Obwandiyag (aka Pontiac)

Chief: Obwandiyag (aka Pontiac)

Born: c.1720 in Great Lakes region, New France

Died: April 20, 1769 near Cahokia, Illinois Country

Nationality: Odawa (Ottawa)

Pontiac was a Ottawa war chief who led one of many Native American struggles against British military occupation, in particular in the Great Lakes region. He was one of the prominent leaders in the conflict referred as Pontiac’s War. Pontiac became an Ottawa war leader in 1747 when he allied himself with New France against the Huron leader Nicholas Orontony. He was an ally of the French during the French and Indian War (1754-1763) against the British. Dissatisfied with British policies after the French and Indian War, a loose confederacy of Native Americans was formed to push the British out of the continent.

On April 27, 1763, Pontiac held a council to urge a surprise attack on Fort Detroit. Pontiac’s war began on May 7, 1763, when Pontiac and 300 of his followers attempted to take Fort Detroit. Eventually, more than 900 warriors from a half dozen different tribes joined the siege. For about six months, Pontiac and his followers laid siege to the fort. On July 31, Pontiac and his supporters held off a British detachment at the Battle of Bloody Run, but were still unable to capture Fort Detroit. By the October of the same year, the siege was lifted and Pontiac and his followers withdrew to the Illinois Country. The influence of Pontiac declined after the failed Fort Detroit siege. Pontiac was assassinated on April 20, 1769, by a Peoria warrior whose name has not been preserved.

Resources about Pontiac:

Pontiac (Ottawa Leader). (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Pontiac's War. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Middleton, Richard. Pontiac’s War: its causes, course, and consequences. New York, Routledge, 2007.

Peckham, Howard H. Pontiac and the Indian uprising. Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1994.

Thayendanegea (aka Joseph Brant)

Chief: Thayendanegea (aka Joseph Brant)

Born: March 1743 in Ohio Country, somewhere along the Cuyahoga River

Died: November 24, 1807 in Upper Canada (present day Burlington Ontario)

Nationality: Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk -Wolf Clan)

Thayendanegea means “two wagers (sticks) bound together for strength” or possibly “he who places two bets”

Joseph Brant was a Mohawk military and political leader who rose to prominence due to his education, abilities and his personal connections. Brant fought in various wars throughout his life time. He participated in French and Indian War, allied with the British he fought with Mohawk and Iroquois allies. He received the silver medal from the British for service. Brant became fluent in English as well as at least three of the Six Nations’ Iroquoian languages. Brant led Mohawk and colonial Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. The Mohawk named Brant as a war chief and their primary spokesman. Brant traveled to London in 1775 to persuade the crown to address past Mohawk grievances in exchange for the Iroquois nations (Six Nations) allying with the British. A promise of land in Quebec was made if they fought in upcoming rebellion in America.

Brant was an active combatant in the American Revolution. The Mohawk were a part of the Six Nations who decided to remain neutral in 1775. In the following year, Brant traveled to multiple villages to urge them to join the war as allies of the British. By July of 1777, the Six Nations had abandoned neutrality and four of the six nations allied with the British. Brant's service is marked by various battles in the New York and Great Lakes areas. After the American Revolutionary War, promises made to protect the sovereignty of the Iroquois domain were ignored by Britain and the United States and land disputes ensued. Eventually, Brant relocated most of his people to Canada where he died in his home on Lake Ontario, on November 24, 1807, after a short illness.

Resources about Joseph Brant:

Joseph Brant. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retreived March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Kelsay, Isabel Thompson. Joseph Brant: 1743-1807, man of two worlds. Syracuse, N.Y., Syracuse University Press, 1984.

Robinson, Helen Caister. Joseph Brant: a man for his people. Toronto, Durndurm Press, 1986.

Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (aka Black Hawk)

War Chief: Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak (aka Black Hawk)

Born: 1767 in Saukenuk, Illinois

Died: October 3rd 1838 in Davis County, Iowa

Nationality: oθaakiiwaki (Sauk)

Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak [Mahkate:wi-meši-ke:hke:hkwa] means "be a large black hawk"

Black Hawk was a war chief and leader of the Sauk tribe in the Midwest of the United States. He was known more for being a war leader, a “captain of his actions” than he was a tribal chief. Black Hawk earned his credentials by leading raids and war parties in his youth. The War of 1812 consisted of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland against the United States where part of it took place around the Great Lakes area. An undeterred Black Hawk and his group of about 200 warriors were allies for the British, and they fought against the U.S. army. It was Black Hawk’s wish to push white settlers away from his people in the Sauk territory. Saddened by the many lives that were lost due to European attack methods, Black Hawk returned home to Saukenuk.

In the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis, the Sauk and Fox, in exchange for an annual payment of goods, both tribes gave up a stretch of land that started in Missouri through most of Illinois, and part of Wisconsin. Black Hawk resented the treaty saying that the tribal leader who had signed it was not authorized to sign treaties. In 1832, Black Hawk led a loose confedaracy of the Sauks, Meskwakis and Kickapoos known as the “British Band”. These tribes made up about 1500 warriors and non- combative people that crossed the Mississippi River into the state of Illinois from Iowa. The intention of Black Hawk was to peacefully regain and settle on tribal land that had been taken by the United States in the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis. When the British Band tried to return to Iowa, there were a number of battles with opposing forces. The last war fought on the east side of the Mississippi River was called the Black Hawk War. After the war, Black Hawk lived with the Sauk in Iowa, he later died after a two week illness. He was buried on a friend’s farm in Des Moines River, Iowa.

Resources about Black Hawk:

Black Hawk (Sauk leader). (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retreived March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Berlo, Janet Catherine. Spirit beings and sun dancers: Black Hawk’s vision of the Lakota world. New York, George Braziller, in association with the New York State Historical Association, 2000.

Drake, Benjamin. The great Indian chief of the west: or Life and adventures of Black Hawk. Cincinnati, Applegate & Company, 1854.

Tekoomsē (aka Tecumseh)

Chief: Tekoomsē (aka Tecumseh (/tɛˈkʌmsə/ te-kum-sə)

Born: March 1768 on the Scioto River, Chillicothe, Ohio

Died: October 5, 1813 near Moravian (Chatham-Kent, Canada)

Nationality: Shaawanwaki (Shawnee)

Tecumseh (/tɛˈkʌmsə/ te-kum-sə) (in Shawnee, Tekoomsē, meaning "Shooting Star" or "Panther Across the Sky", also known as Tecumtha or Tekamthi)

Tecumseh was a leader of the Shawnee and a large tribal confederacy which opposed the United States during Tecumseh's War and became an ally of Britain in the War of 1812. He was considered a natural and charismatic leader and participated in numerous conflicts on the frontier. Growing up during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War, Tecumseh developed a vision of an independent Native American nation east of the Mississippi under British protection as colonists moved further west. He is known for Tecumseh’s War which led into the War of 1812, during which the Siege of Detroit and the Battle of Thames took place.

During the first decade of the nineteenth century, Tecumseh’s younger brother Tenskwatawa became known as “The Shawnee Prophet." The Prophet’s teachings attracted followers from other tribes and led to increased tensions between settlers and his followers. Tecumseh emerged as the primary leader of the confederacy of tribes who followed his brother's teachings. In 1810, a confrontation between Tecumseh and Indiana Territory governor William Henry Harrison regarding rescinding a treaty, led to an alliance with the British. In September 1811, while Tecumseh was traveling to recruit allies, Harrison and 1,000 men moved on Prophetstown and destroyed the town. The Battle of Tippecanoe was a setback, but Tecumseh continued building allies when he returned from the South. In 1812, allied with the British, Tecumseh’s confederacy lay siege to Detroit, this victory was reversed the following year. Tecumseh was killed in October 1813 during the Battle of Thames, near Moraviantown. The death of Tecumseh led to the disbanding of his confederation and further western movement of Native Americans.

Resources about Tecumseh:

Tecumseh. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Calloway, Colin G. The Shawnees and the War for America. New York, Viking, 2007.

Laxer, James. Tecumseh & Brock: the War of 1812. Toronto, House of Anansi, 2012.

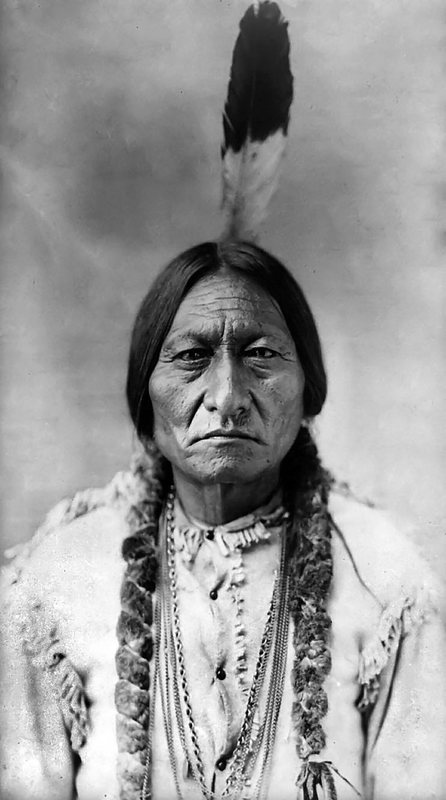

Tatanka-Iyotanka (aka Sitting Bull)

Chief: Tatanka-Iyotanka (aka Sitting Bull)

Born: Jumping Badger 1831 in Grand River, Dakota Territory

Died: December 15, 1890 in Grand River, South Dakota, Standing Rock Indian Reservation

Nationality: Lakota (Sioux)

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota military, religious, and tribal chief who led his people through many years of resistance to government policies in the United States. He was a stalwart defender of his people’s land and ways of life which were threatened by the intrusion of white settlers on treaty guaranteed tribal territories. The United States government made great efforts to settle Native Americans on reservations. These violations provoked a vision in Sitting Bull’s mind in which he envisioned the defeat of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Thus this brought upon the “Battle of the Little Bighorn” in which Sitting Bull, and other war leaders victoriously masterminded the defeat of U.S. troops that included killing Custer a lieutenant colonel, and all of his men.

After this massive victory, Sitting Bull and his followers were faced with a U.S. military counteroffensive, so they fled for Canada to Wood Mountain, North West Territories which is now Saskatchewan. Sitting Bull returned to U.S. territory in 1881 where he surrendered to U.S. forces, and was held prisoner of war for two years. After his release Sitting Bull settled on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation which is now present day North Dakota. He became a successful famer, and also joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Sitting Bull remained a steadfast critic of U.S. Indian policy, and in 1890 agent James McLaughlin ordered his arrest. His cabin was invaded and a struggle ensued. Sitting Bull was shot in the head and killed. He was buried in Fort Yates, North Dakota.

Resources about Sitting Bull:

Sitting Bull. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Lehman, Tim. Bloodshed at Little Bighorn: Sitting Bull, Custer, and the destinies of nation. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. New York, Viking, 2010.

Kintpuash (aka Captain Jack)

Chief: Kintpuash (aka Captain Jack)

Born: 1837 Tule Lake area, California

Died: October 3, 1873 Fort Klamath, Oregon

Nationality: Modoc

Kintpuash or Captain Jack was the chief of the Modoc people in both California and Oregon. His name in the Modoc language was “Strikes the Water Brashly”. He was the only Native American leader to be charged with war crimes. Kintpuash and his Modoc tribe lived near Tule Lake along the California and Oregon border. After the European invasion Kintpuash and his tribe were forcibly removed by white settlers to the Klamath Indian Reservation in southwest Oregon. The Klamath tribe already occupied this land, and with the arrival of the Modoc’s the two tribes became rivals. After being poorly treated by the larger Klamath tribe, in 1865 Captain Jack led his family, and the Modoc people back to their lands in California. In 1869 the Modoc tribe was rounded up by the United States Army and taken back to the Klamath Reservation. The following year in 1870 Kintpuash once again led his people back to Tule Lake, California.

This back and forth escapade instigated the Modoc War in 1872-1873. The United States Army was sent out once again to round up Captain Jack, and his tribe of Modoc’s to have them sent back to the Klamath Reservation. During negotiations a fight broke out between a U.S. soldier, and one of the Modoc men. This encounter brought about the “Battle of Lost River”. Kintpuash then escorted his people to the Lava Beds National Monument in northeastern California. In 1873 the United States Army located the Modoc’s, and a war broke out. Captain Jack eventually killed the army’s general Edward Canby, and Modoc warrior Boston Charley killed a California minister Reverend Eleazar Thomas. Kintpuash was captured and turned in by one of his own people. He was tried by a military court, and was found guilty of the two murders. Captain Jack was hanged on October 3, 1873.

Resources about Kintpuash:

Kintpuash. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Payne, Doris Palmer. Captain Jack, Modoc renegade. Portland, Oregon, Binford & Mort, 1938.

Wilma Mankiller

Chief: Wilma Mankiller

Born: November 18, 1945 in Tahlequah, Oklahoma

Died: April 6, 2010 in Adair County, Oklahoma

Nationality: Ani-Yunwiya (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ) (Cherokee, also Dutch and Irish descent)

The family surname, Mankiller, refers to a traditional Cherokee military rank; it is Asgaya-dihi

Wilma Mankiller was the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation. She served for 10 years. Wilma Mankiller’s political career began in 1983 when she was first elected deputy chief of the Cherokee Nation. In 1985 she launched a campaign, and was elected primary chief of the Cherokee Nation between 1985 and 1995. Mankiller was the only female that ever served as chief of the Cherokee’s in a male dominated leadership role. During her tenure as chief Mankiller reinvented the Cherokee community with numerous projects. Tribally owned businesses were created that included horticultural and plant establishments. In the Bell community of Oklahoma running water was established, and a hydroelectric facility was built. Also the Cherokee Nation Community Development Department was founded by Mankiller and her administration. Together they increased the population of the Cherokee Nation from 55,000 to 156,000. “Prior to my election,” says Mankiller, “young Cherokee girls would never have thought that they might grow up and become chief.” [3]

Mankiller achieved several rewards throughout her lifetime, and in 1993 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. She also wrote an autobiography called Mankiller: A Chief and Her People. Mankiller’s personal life was not easy as she was involved in an almost deadly car accident in 1979, and had multiple surgeries thereafter. She also had several other health issues that included breast cancer, myasthenia gravis etc. Against all odds she managed to overcome her ailments, and became a legacy for the Cherokee Nation. In 2010 Wilma Mankiller died of pancreatic cancer in her home in Adair County, Oklahoma.

Resources about Wilma Mankiller:

Wilma Mankiller. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retreived March 1, 2016 from Wikipedia.

Janda, Sarah Eppler. Beloved Women: the political lives of Ladonna Harris and Wilma Mankiller. DeKalb, Ill., Northern Illinois University Press, 2007.

Mankiller, Wilma and Wallis, Michael. Mankiller: a chief and her people. St. Martin’s Press New York, 1993.

Osceola

Chief: Osceola (aka Billy Powell)

Born: 1804 in Maskókî or Creek village of Talisi, now known as Tallassee, Alabama near present day Tuskegee AL

Died: January 30 1838, Fort Moultrie, South Carolina

Nationality: Creek (also Scots-Irish and English)

Osceola (/ˌɒsiːˈoʊlə/ or /ˌoʊseɪˈoʊlə/). This is an anglicized form of the Creek Asi-yahola (pronounced [asːi jahoːla]); the combination of asi, the ceremonial black drink made from the yaupon holly, and yahola, meaning "shout" or "shouter".

Osceola was an influential Florida Seminole leader. For almost two years, he led a band of warriors in resistance against the United States during the second Seminole war. He was born Billy Powell, in Maskókî or Creek village of Talisi, now known as Tallassee, Alabama. He was the son of Polly Copinger (Tallassee woman) and William Powell (English trader). He was raised in Creek traditions. When Billy was born, many of the people in his village were of mixed blood Indian/English/Scottish with some African blood thrown in for good measure. The Creek nation had lived along the Tallapoosa River in present day Alabama for generations. In 1814, after the Red Stick Creek were defeated by US forces, Polly migrated to Florida along with other Creek refugees and joined the Seminole where Billy grew to adulthood and was given the name Osceola.

European-American settlers pressured the United States government to remove the Seminole from Florida, especially after the US had acquired Florida from Spain. The further encroachment from settlers led to many skirmishes between Seminoles and the military. Lands were seized and the Seminoles moved farther south into Florida. Additional pressure was laid upon the Seminoles to agree to sell their land and move to lands west of the Mississippi. In 1832, the Treaty of Payne’s Landing was signed by a few chiefs, but others do not agree to the removal. In 1835, Osceola and his warriors murdered an Indian agent who had locked him up. For the next two years, Osceola led a successful resistance which is regarded as the second Seminole War. He was captured in October 1837, when he went for peace talks. The deceit involved in his capture led to a nationwide uproar. Apparently, very ill at the time of his capture, Osceola died in prison on January 30, 1838.

Resources about Osceola:

Osceola. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 27, 2017 from Wikipedia.

Wickman, Patricia R. Osceola’s Legacy. (Fire Ant Books). N.p.:U of Alabama, 2006.

Hatch, Thom. Osceola and the Great Seminole War: A Struggle for Justice and Freedom. New York: St. Martin’s, 2012

Wovoka

Chief: Wovoka (aka Jack Wilson)

Born: c.1856 Smith Valley, Nevada, southeast of Carson City

Died: September 20 1932, Yerington, Nevada

Nationality: Numu (Northern Paiute)

Wovoka means cutter or wood cutter in Northern Paiute.

Wovoka was a Numu seer, holy man and prophet of the 1890 Ghost Dance movement. Ghost Dance movements have occurred in history as a rallying point to preserve traditional Native American culture and as a form of resistance to U.S. policy and American culture. Born somewhere between 1856 and 1863, Quoitze Ow was Wovoka’s birth name. From about age 8 on, Wovoka worked on the Mason Valley ranch of David and Abigail Wilson. He became more commonly known by the name Jack Wilson after working on the Wilson’s ranch for years. Growing up with shaman and prophecy traditions, it was in the company of the Wilsons where Wovoka was exposed to Christian theology. Wovoka was trained as a “weather doctor” following in his father’s footsteps. He was also known through Mason Valley as a spiritual leader.

On New Year’s Day 1889, during a solar eclipse, Wovoka had a vision. He related traveling to heaven and meeting God. His vision predicted the rise of Paiute dead and the removal of whites in their entirety from North America. In order to bring this prophecy to pass Native Americans needed to live righteously, create cross cultural relations with other Nations and perform a traditional round dance - The Ghost Dance. This religious movement came to be incorporated into a number of Native American belief systems. Wovoka’s messages included teachings of nonviolence, but due to the troubled history between Native Americans and whites settlers, the performance of the Ghost Dance was not received as peaceful by non-Natives. The massacre at Wounded Knee in Dec 1890 brought an end to the public practice of the Ghost Dance, instead it went underground. Wovoka remained a spiritual leader and healer until his death in 1932.

Resources about Wovoka:

Wovoka. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 27, 2017 from Wikipedia.

Wovoka. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 27, 2017 from Wiki/Ghost Dance.

Hittman, Michael, and Don Lynch. Wovoka and the Ghost Dance. Lincoln:U of Nebraska, 1997.

Reilly, Hugh J. Bound to Have Blood: Frontier Newspapers and the Plains Indian Wars. Lincoln:U of Nebraska, 2011

About This Exhibit