A codex is essentially an ancient book, consisting of one or more quires of sheets of papyrus or parchment folded together to form a group of leaves, or pages. This form of the book was not widely used in the ancient world until around the second century AD, when it slowly but steadily began to replace the traditional book form, the papyrus roll.

|

|

A codex (left) compared to a roll (right). |

|

Papyrus had been used as a writing material in Egypt for thousands of years, and during the classical period papyrus rolls were exported throughout the ancient world. Any reader or writer, from the philosophers of ancient Greece to the emperors of Rome, would have been familiar with the papyrus roll as the normal form of the book. Typically about 12 inches tall and a hundred feet or more in length, papyrus rolls could be used to record long works of literature, or cut into smaller pieces to write letters or other short documents.

For some reason, however, early Christian literature began to be written not on rolls, but in codices. The reasons for the shift from roll to codex are uncertain, yet over the course of a few hundred years the roll became obsolete, permanantly replaced by the form which would evolve into the modern book. Beginning around the fourth century, parchment began to replace papyrus as the preferred writing material, and parchment manuscripts remained the most common form of the book until the advent of paper and moveable type. Thus, codices made from papyrus are both very old and very rare; few were known to exist until the vast discoveries of papyri that ocurred during the twentieth century.

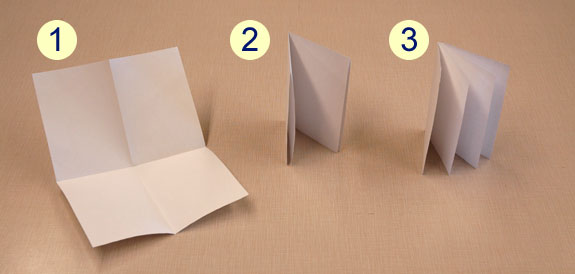

P46 is an example of a relatively old and rare form of codex, the single-quire codex. Most codices, like modern books, are formed from multiple quires (groupings of typically 4, 8, or 16 leaves), bound together side-by-side. The illustration below shows how a typical four-leaf quire can be formed from a single sheet of papyrus, parchment, or paper by folding and then cutting the sheet:

P46, however, consists of a single quire, which could be formed by simply taking a stack of papyrus sheets and folding them all in half. This method produces a codex in which the first leaf is physically joined to the last, with the remaining leaves sandwiched between. Because P46 used this unique form of construction (which eventually died out due to its impracticality), the precise size of the codex can be determined by simply knowing the page numbers of any conjugate pair of physically joined leaves. This is true because the number of leaves preceeding any given page is equal to the number of leaves following its conjugate pair.

Thus, even with only a fragmentary version of the codex, papyrologists could determine that the codex consisted of 104 leaves, using the following reasoning: Pages 48 and 159 form a conjugate pair. Obviously 47 pages preceeded page 48, and so 47 pages also followed page 159, for a total of 206 numbered pages. Since the first page was left blank (numbering began with the first left-hand facing page), this means that the codex consisted of 208 pages, or 104 leaves. This no trivial fact, since knowing the number of leaves is an important factor in determining what could have been written in the lost sections of the codex.